Seeking the perfect weekend and summer getaway from the stress of New York City life, Hollywood celebrities, Broadway stars, artists, writers, and dancers began flocking to Fire Island in the 1930s. The outer barrier island on Long Island’s south shore became an idyllic escape — but the island known to some as “The Graveyard of Ships” was not without its dangers.

On the 21st of September, the Great New England Hurricane of 1938 devastated the island with wind gusts at 200 km per hour and 5.5-meter waves. Cheekily known as the Long Island Express, the storm demolished the boats and buildings alike; less than a score remained intact at the celebrated beach colony of Cherry Grove. Of those still standing was Duffy’s Hotel, which soon became a favourite haunt for the LGBTQ community in the years before Stonewall.

In the early 1940s, bohemians, nudists, and squatters began making their way to the Fire Island Pines, creating a second haven for queer society, which was forced underground by repressive laws and undisguised bigotry. The Pines became a secluded oasis where people could safely express their gender and sexuality without fear of violence or arrest.

That same decade, halfway around the globe, Patrik Moreton (1942–1995) was born to British parents in northern India. The family lived there until India achieved independence in 1947, and then returned to London. Patrik grew up under the shadows of the Age of Austerity, then came into his own as Swinging London took root. He dreamed of becoming an actor in the theatre, then found his true calling doing hair, designing wigs at a Mayfair salon before landing his first cover at British Cosmopolitan.

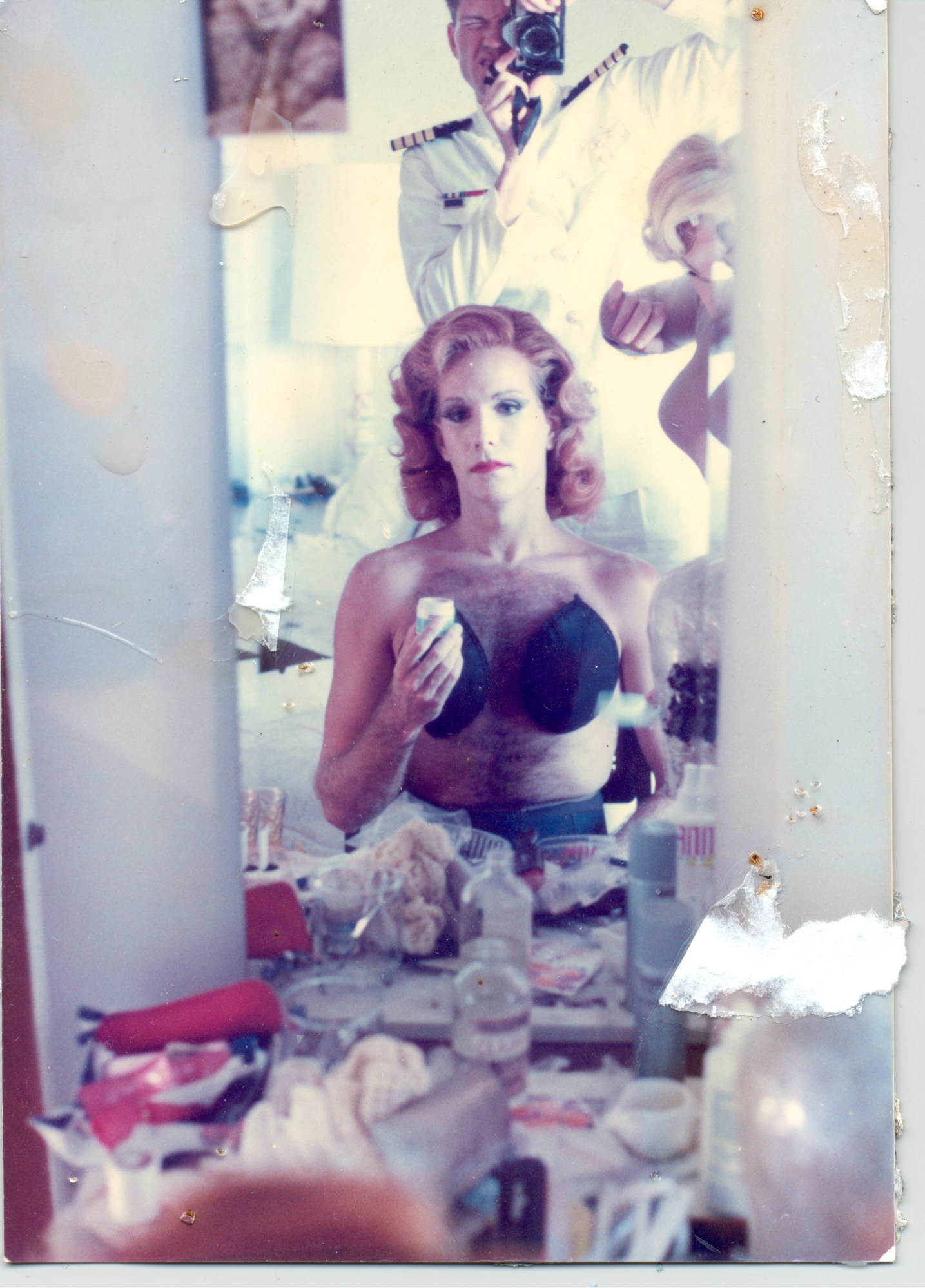

Possessed with a vision of taking his passion to the grandest stage of them all, Patrick took New York by storm doing hair and makeup for legendary Broadway shows like The Elephant Man with David Bowie, Cabaret, My Fair Lady, Pippin, and Little Foxes. Many of the productions drew from golden age Hollywood films. In the 1950 movie Sunset Boulevard, Gloria Swanson, starring as reclusive film star Norma Desmond, famously said, “We had faces then.” It was a sentiment Patrik understood and adopted as his own, creating an alter ego Marlene Dietrich, the legendary German actress who embodied Weimar decadence, for his fabled Fire Island soirees.

A longtime resident of the Pines, Patrik regularly hosted and attended house parties where guest pulled out their finest gowns and jewels, dressing in themes for events like Royal Wedding, Miss America, Mildred Pierce, and Arabian Nights. Moving seamlessly through the scene with a camera in hand, Patrick documented the fabulous social events of the season, amassing an extraordinary archive of snapshots chronicling the era between 1984-1994. After Patrik’s death from AIDS in 1995, Chris Lipari, his Fire Island housemate, donated the collection to the LGBT Community Center National History Archive at The Center in New York.

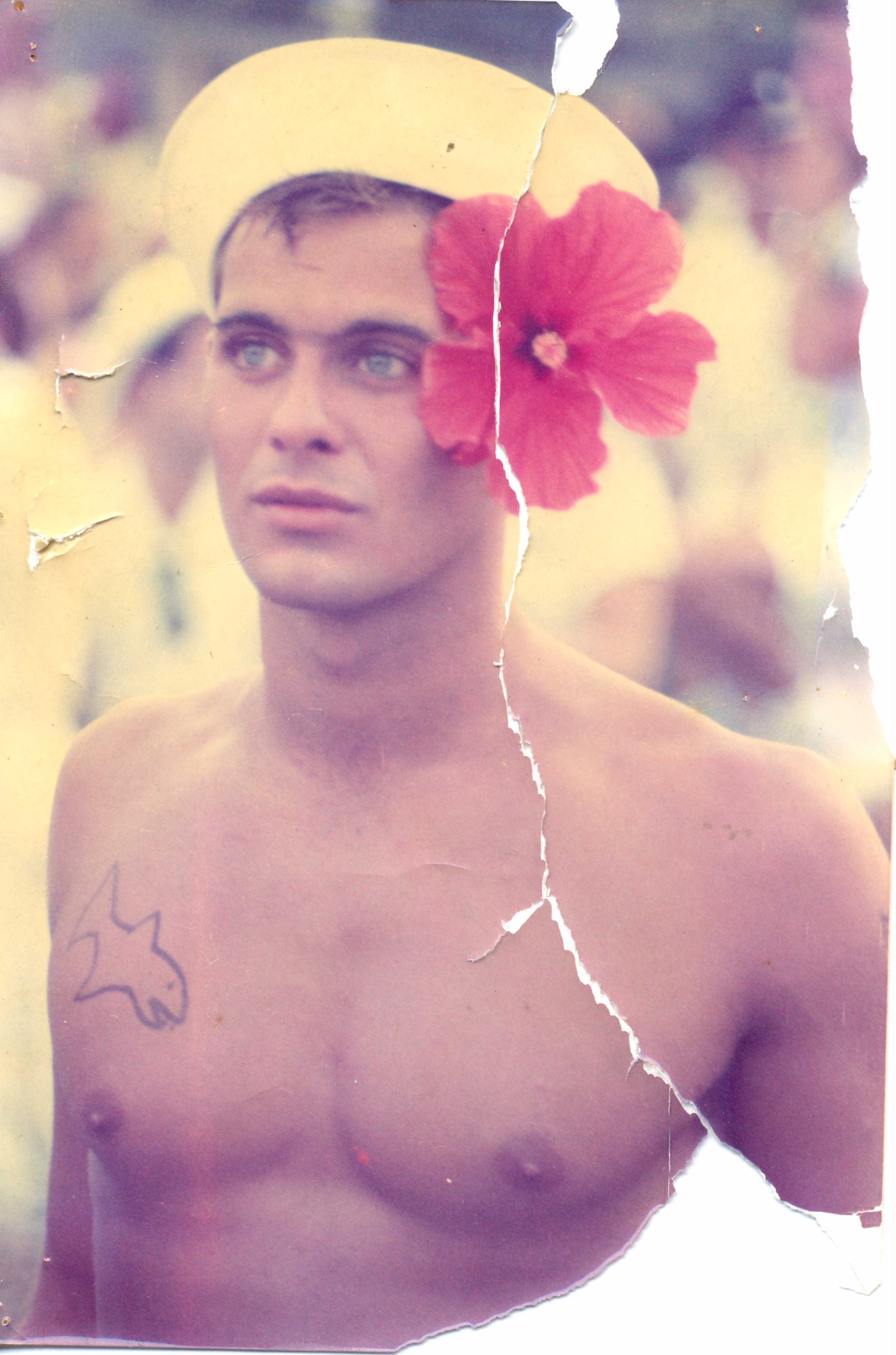

“The photographs are fragments that have been removed from photo collages,” says Matthew Leifheit, author of To Die Alive (Damiani), who is doing research at the Archive. “Some of them are almost full-size snapshots, but most of them are cut into smaller shapes and are housed in plastic sleeves. As you turn the pages, they move and reconfigure themselves in a kaleidoscopic way as they shift within the sleeve. When you look at them, they are in a beautiful state of being in flux even though they are inert, archival materials.”

Patrik’s collection preserves an extraordinary era of LGBTQ life as the joyous freedom and unrestrained hedonism of early years of the Gay Liberation Movement came to a horrific end with the emergence of the AIDS crisis in 1981. Although Patrik’s parties began as purely social events, they soon evolved into charity fundraisers to help those affected by HIV, which at that time was a death sentence.

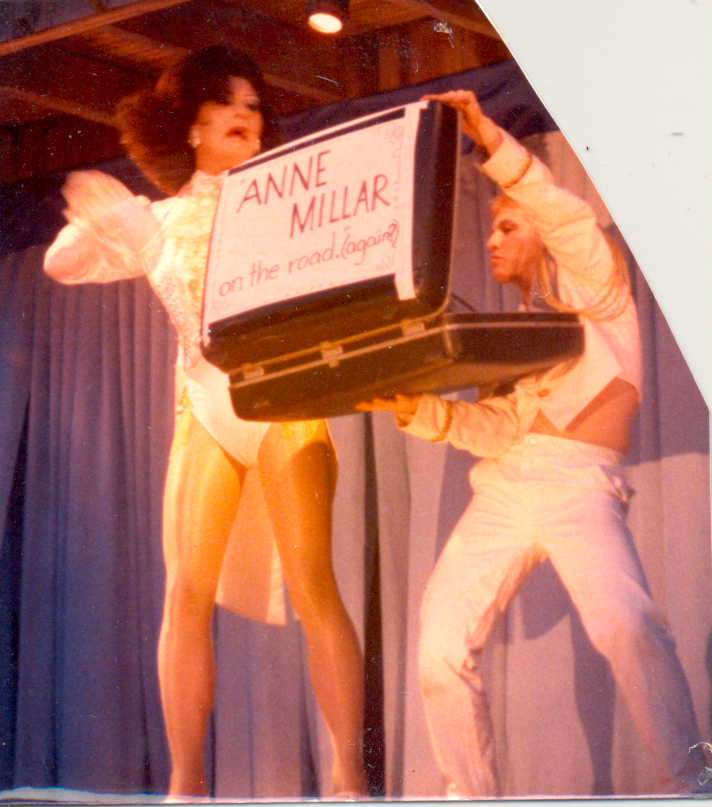

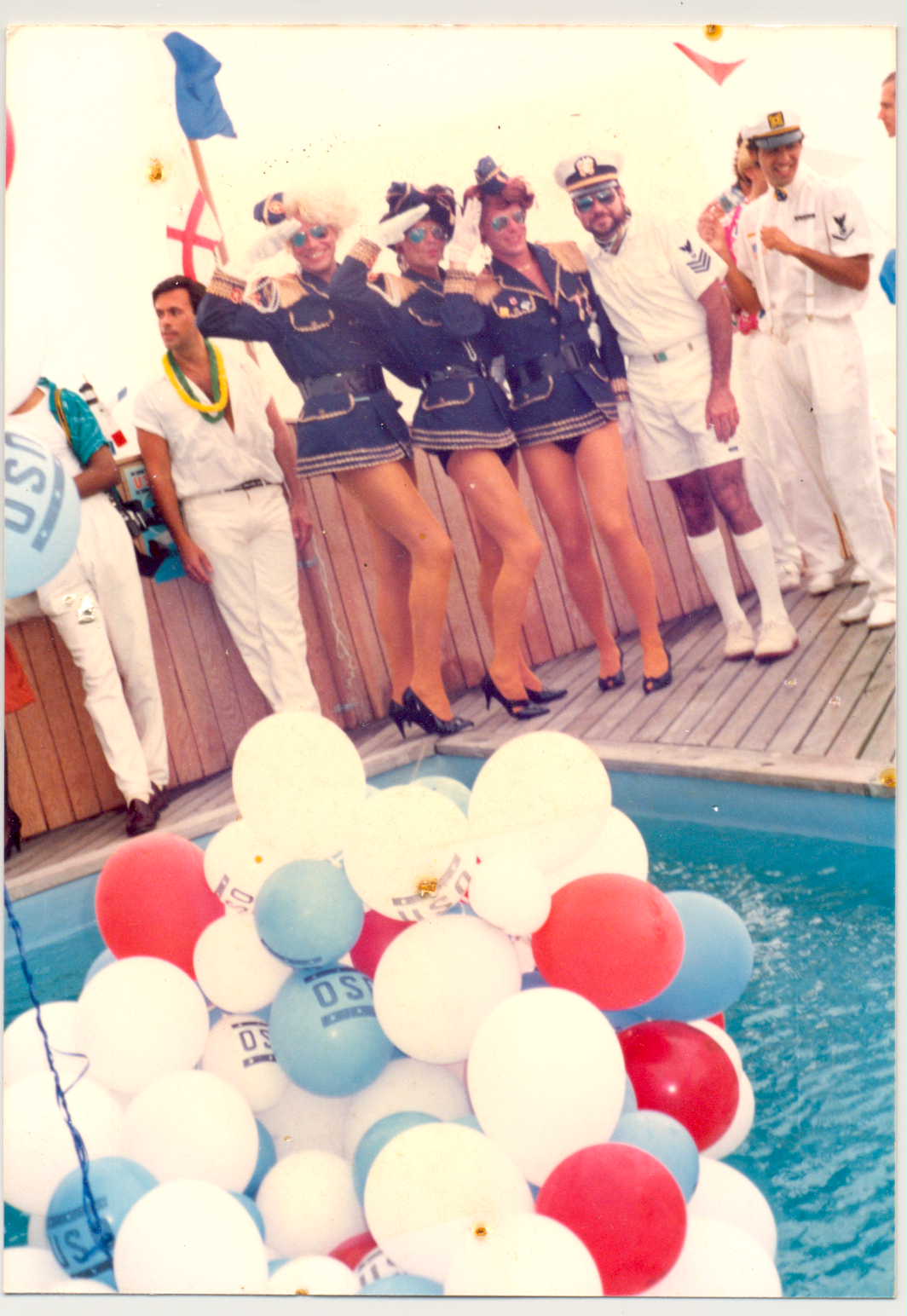

Between 1988-1994, Patrik and the group house at 439 Sail Walk — known a “Sailors House” — organised the annual Hollywood Shore Leave Party to raise money for AMFAR (American Foundation of AIDS Research, and PWAC (People with AIDS Colation). Held on the 4th of July, the party took its cue from USO shows held during World War II when Hollywood stars travelled to military bases to lift the morale of soldiers on the frontlines.

Months in the making, the event attracted nearly 1,000 “starlets” and “sailors” inspired by the Golden Age of Hollywood. The Hot Lavender Swing Band took the stage while Broadway star Larry Kent performed. Patrik appeared as Marlene Dietrich, co-creator Aldyn McKean as Carmen Miranda, producer David Merrill as Rita Hayworth, actor Robert Donnelly as Ann Miller, and others as Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. The party even boasted its own Water Ballet featuring “Esther Williams” and friends.

Being a young child when these stars were at their height, Patrik and other gay men of his generation emulated these iconic displays of beauty, elegance, and grandeur. “What I love about seeing this collection is that it’s a rich trove of gay tropes and archetypes,” Matthew Leifheit says. “I have been researching the character of the gay sailor, which has been depicted throughout history in Jean Cocteau drawings and Paul Cadmus’ painting “The Fleet’s In”. It’s based on a historical relationship between queer people and the military, which is a really subversive topic to even discuss to this day.”

Military personnel who contracted HIV during the 1980s described the harrowing treatment they received while enlisted, sent to housing known as “the leper colony“. President Ronald Reagan refused to publicly say AIDS until 1985, while members of his administration went so far as to joke about it as a “gay plague” during a 1982 press conference.

Refusing to be cowed by government, media, corporations, and the church abjectly stigmatising the LGBTQ community, Patrik and his cohorts pooled their resources to create spaces of love, celebration, and camaraderie. “As the Pines community continued to suffer incalculable losses from the AIDS epidemic, the energy to produce these house parties seemed to wane and was replaced by what seems to be an endless list of fundraising benefits,” Chris Lipari, Patrik’s Fire Island housemate, wrote in a statement accompanying the collection. “To this day, hardly a weekend goes by when there is not some event happening designed to raise money for a worthwhile cause.”

Indeed, Patrik’s final Shore Party in 1994 was no less than a benefit for The Center itself. “After his death, Chris Lipari, his Fire Island housemate, donated Patrik’s archive in 1997,” Caitlin McCarthy, Archivist at The Center, says. “It could have been the benefit that led to that, or it could have been the interconnected LGBTQ networks in Manhattan and Fire Island. There is a real poignancy to how queer folks have gathered at the beach, whether that’s on Fire Island, at Jacob Riis Beach in Queens, or Atlantic City. It is necessary to have a place you can gather and feel safe in your body.”

Reflecting on the urgencies that arose from the early AIDS crisis, Caitlin points to the creation of the Archive in 1990 as a material necessity much like the charity benefits themselves. Unlike the paper-based document, interview or audio recording, Caitlin sees what they describe as “something caught in time in the photograph. You can look at them and receive information from them. It connects us back to an earlier time period and people who were coming together in the face of trouble and the name of joy. I see that happening today, and I’m just in awe of our resilience as a community.”

Although the parties ended long ago, the photographs preserve these extraordinary moments of faith, hope, and love in the face of insurmountable odds. “Patrik felt it was important to come together and experience joy during those years — and to record the parties,” Matthew says. “He was a gifted photographer, and the drama of the torn, fragmentary images increases the pathos. It’s amazing these photographs have survived.”

Credits

Photography Patrik Moreton from Patrik Moreton Fire Island Snapshots courtesy of The LGBT Community Center National History Archive