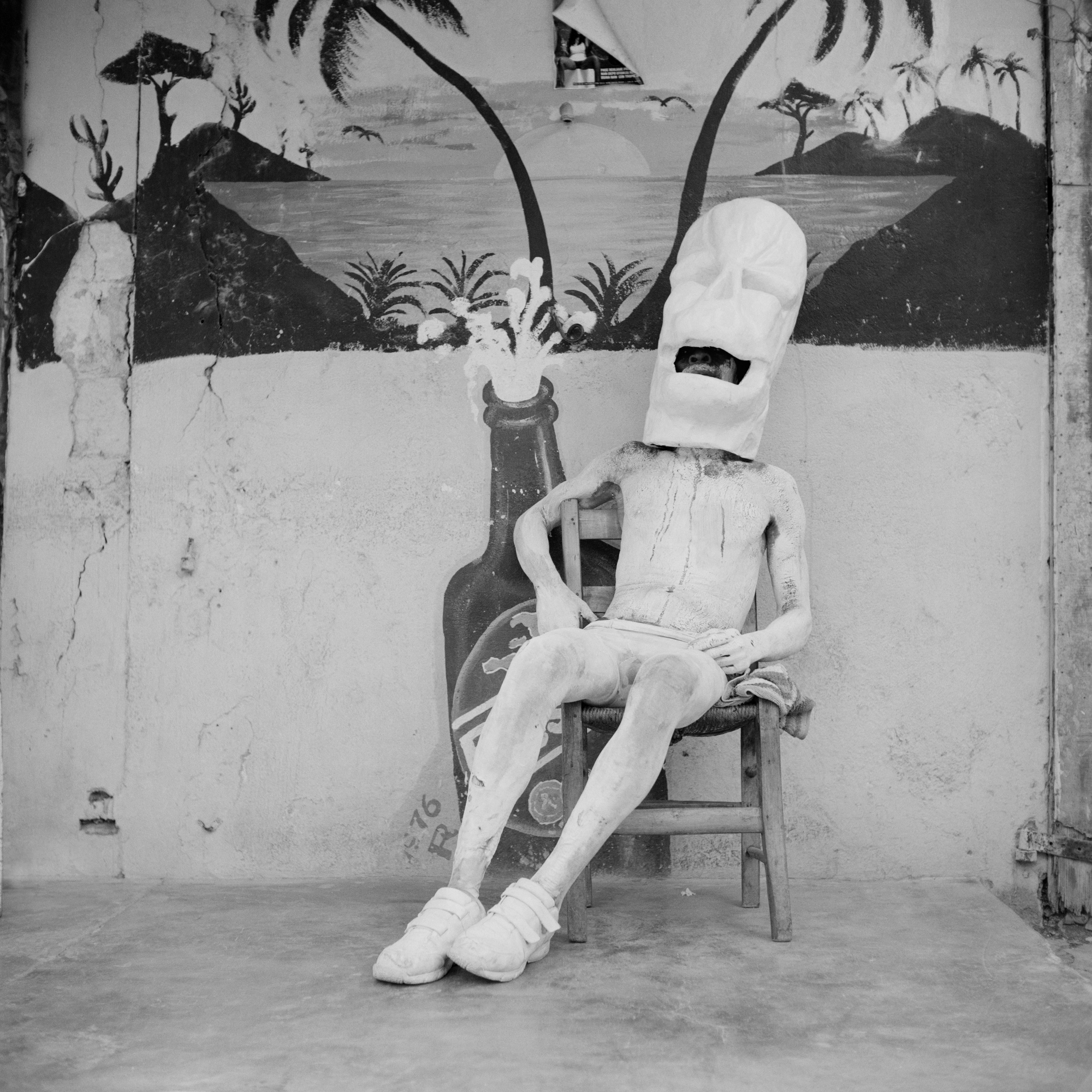

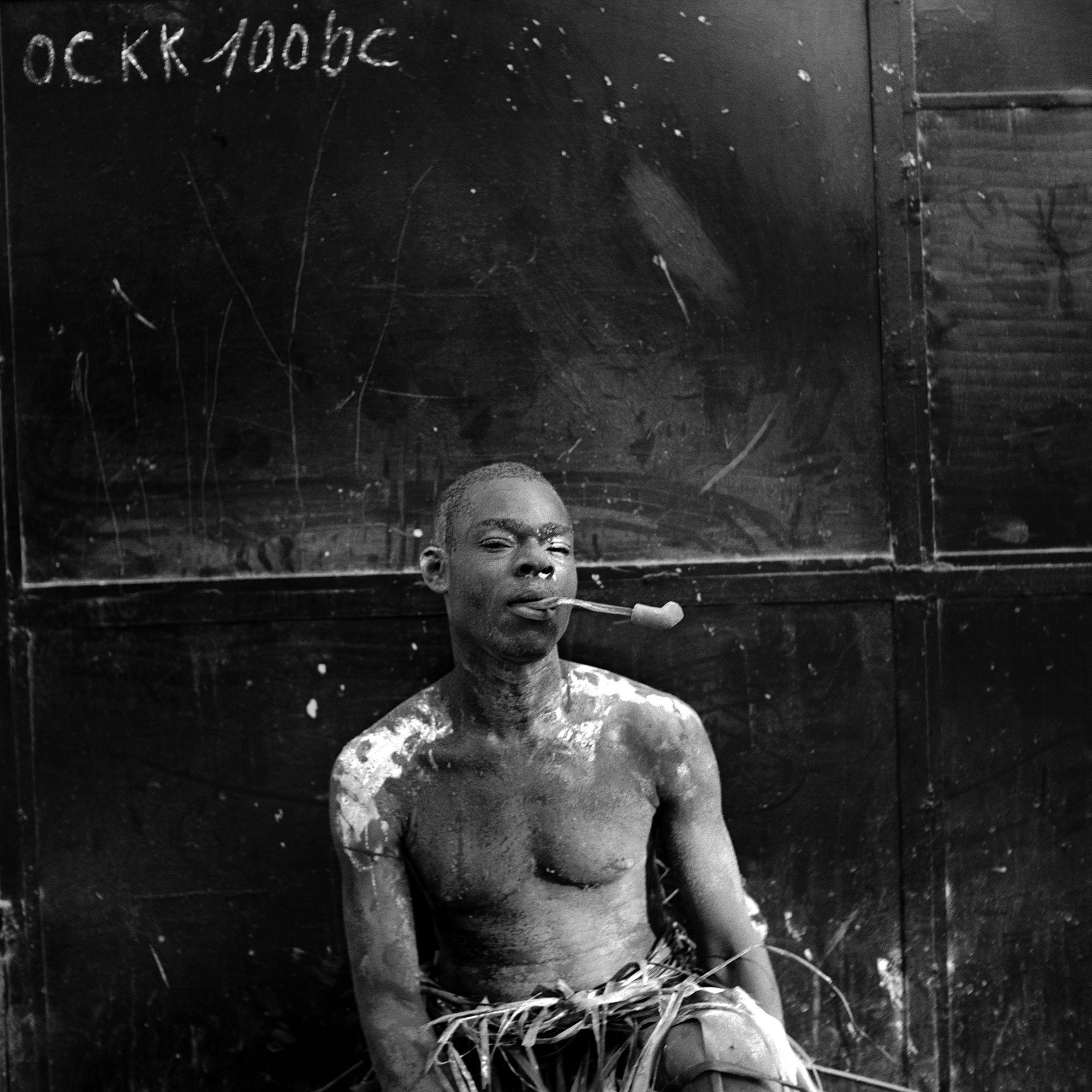

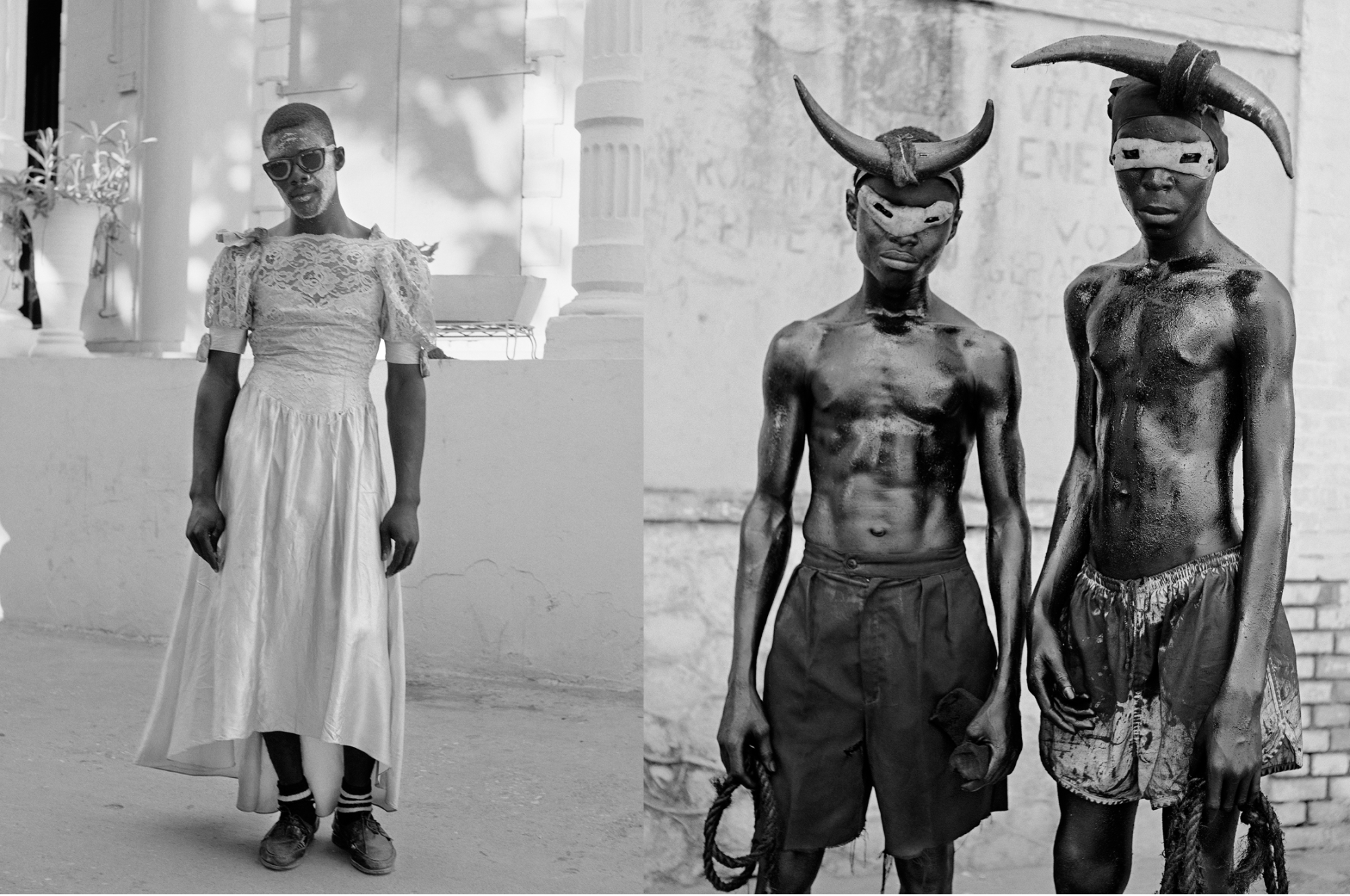

Leah Gordon‘s show “Kanaval“, currently on view at MOCA North Miami, captures 20 years of exuberant carnival street entertainment in Haiti through a series of enthralling black-and-white photographs. The visuals — replete with elaborately masked, veiled and body-painted figures — recreate longstanding tropes, and are paired with excerpts of stories reflecting the mythology prevalent in Haitian history and culture.

As the co-director of the “Ghetto Biennale” in Port-au-Prince and a former curator of the Haitian Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale, Leah has long been documenting this territory. Her film Kanaval: A People’s History of Haiti in Six Chapters — which aired on the BBC at the end of last year — provides an in-depth perspective on ancestral traditions, spirited festivities and political flux; executed in a dreamy aesthetic that deliberately engages with the rich heritage even as it confronts erasure, turmoil and violence.

Standing among her works at MOCA during Miami Art Week, we spoke with Leah about using old-school equipment to create a timeless feel, acknowledging uneven power dynamics outright, and translating relationships to gender and costume across cultures.

Knowing that this project started in the 90s, I was wondering how (or if) your process has changed?

It probably hasn’t. I use this very old-fashioned camera, which is all mechanical. It’s the same camera that’s taken all these pictures since 1995. It forces ethics upon you, as well as aesthetics. I have to stop, I have to speak to people — you can’t just take a quick snap — because I shoot on film using a Rolleicord. It’s a twin lens reflex camera: a little square box with two lenses, and you look down. That has a different effect on the reciprocity between yourself and the sitter, because you’re not hiding yourself. It’s far less aggressive. It doesn’t have a kind of erection pointing out, you know: it’s sort of feminist, I would say. I speak Creole, so I can stop people, speak to them, tell them what the project is. Also, I always give a photograph. Overall I think there’s a kind of continuum.

True — from the viewer’s perspective, you can’t feel a difference, timeline-wise, between one image to the other, despite the fact that you’ve been doing this for over two decades.

I tend to just find a nice distressed wall. I’ve spent all these years keeping the carnival out of the pictures. I’ve been very much concentrating on the person and the costume and the story they’re telling. That’s why colour would have been too distracting. I wanted to be able to look at these incredible costumes and try and understand: what are these histories that are seeping through?

A photograph: what does it do? In a way, it strips a lot of meaning, and creates spectacle. And the parade does the same. I realised that when I saw all these guys on side streets… they were acting out this incredible street theatre and I knew there was meaning to it, which is why I did the oral histories. I became very aware of how the camera can spectacularize and decontextualise — and so can the parade. So that’s why I wanted to put the oral histories back with the costumes, with the images.

Can you talk about your relationship to the country more logistically: how you came to speak Creole, how you started going?

Such a ridiculous anecdote. In 1991, I’d done a degree in photography. At the time, I was a van driver for the Communist Party of Great Britain. I was never a member, actually, because I was a member of the Trotskyist party. So I did have a background in revolutionary politics. But the Communist Party I find a bit too Marxist/Leninist. So I had this great van with a red star on the front, and used to deliver books to bookshops everywhere.

It was the middle of winter and snowing. This woman was the sort of BBC ‘Lady Di’ presenter on the holiday program – a bit, like, you know, a national treasure. And she was in the Dominican Republic saying, “What a fantastic place for a family holiday! I must warn you though, it shares an island with another country called Haiti — do not go there by mistake. It has dictatorship, military coups, black magic, Voodoo, and DEATH!” And I just went, ooooh — all that and hot weather!

I went to the book warehouse I worked for and saw that Haiti had been written out of the history of revolution. Even as a member of a socialist revolutionary party! All the time talking about the Russian Revolution, but hardly any mention of the slaves’ revolt [Haitian Revolution]! That was shocking to me, that I didn’t know about it. It was such an incredible history that I just had to go there. So I handed in my notice and a month later, I was on a plane to Haiti.

Incredible! Not speaking any Creole at that time?

I kind of did tapes. So I went in 91; started this project 95. Then in 2006, I met my partner. And then, of course, you know, pillow talk: your Creole suddenly gets very good. And he’s also an artist, so we work together and we run the Ghetto Biennale [in Port-au-Prince] together. Eugène is Haitian, he’s majority class — kind of ‘lower class’. When I’ve now gone back with him, he’s got that language: he doesn’t get divided by class, and my creole is very kind of ‘street’. I mean, not like I did that on purpose – but he’s the only person I hear.

The cultural discourse today is very sensitive about who tells stories. Despite your very clear immersion and passion, have you received any criticism from a racial point of view?

You know, I’ve been going there for a long time. Being a white photographer representing people in Haiti, I’m very aware of Haiti’s history and the demonisation of Haiti, how it started the minute they had the slaves’ revolt [Haitian Revolution]. That demonisation was through the visual representation of Haiti. So without any context, photographs may just feed straight back into that same demonisation.

I do everything very thoughtfully. I mean, you cannot remove the power imbalance of who represents who. But I think you can find mechanisms to try and negotiate that. Even if you can’t get rid of it, I think it’s best actually to reveal it. I made a film in Haiti where I had people speak about me or speak to me. I kept that in. You know what I mean? If you can’t take it away, you can reveal it.

You acknowledge that it’s part of reality.

Yes. And then I did this other project called The Caste Portraits, which is about how, in colonial times, they had this bizarre, quite surreal naming — by a French guy — of the different scales of skin colour in Haiti.

Oh, my God! Like a racist Pantone system?!

He started from one to nine and then he just went mental. He had about 250 variations. And so I did a set of portraits based on Renaissance portraits, but at one end, I had [my partner] Eugène as Black. And on the other end, I had myself as white.

It’s ironic that it’s a racist classification system… I kind of put myself in there to say, “I’m in there. I’m acknowledging my culpability in the history as well.” I’m from a white working-class family in the north of England. You cannot look at the creation of the British working class without looking at the plantation system. They are inter-involved histories: you cannot see them as parallel. Because I’m a kind of ‘good old fashioned revolutionary’ with a socialist background, I think a revolutionary history has to be a world history. I really do. That’s what we’re trying to do with the film, to show how this is a silenced history. But it affected everything. I mean, it’s a major revolution. And it absolutely changed — whilst no one would admit it at the time — the thinking about slavery. It broke the nerve of the colonialists.

You used this beautiful vintage apparatus to create these still images. The aesthetic of the film also has this kind of “out of time” quality. Can you talk about that — how was that achieved?

With the cinematographer Joel Honeywell, we talked a lot about how to shoot the carnival, and Joel suggested we shoot in black and white. It was a pragmatic decision because carnival revellers in colour, you don’t even want to look at it, it’s…

…visual cacophony.

Exactly. So he used that beautiful anamorphic lens — those long thin ones. That was our way of finally allowing the carnival in, in black and white. And then we did the same thing: taking each character away from the centre to a more non-carnival area of the town. That’s where we use the beautiful colour. Joel created, in simplistic terms, a filter — he creates his own lenses. He had this one 48 millimetre lens, we used to call it the mystical lens. It kind of catches flare, but flare in the most beautiful way. It’s got this softness.

In the film, an older woman being interviewed was saying she wished that women had more of a role in the carnival. Men are dressed up as women, but there are no actual women depicted here — are women excluded from the carnival?

It’s a difficult thing. I think when you have an informal economy, as you do in Haiti, men’s status comes less from their employment and more about how they perform on the streets. The way in which you are performing is part of your social status. But I think it’s changing now, bit by bit.

Kanaval is currently on show at London’s Ed Cross Fine Arts until February 18. A book of the same name, published by Here Press, is also available here.