When Robin Graubard came of age in the 70s and 80s, against the backdrop of the Lower East Side punk scene, her camera guided her through the extravagant universe of leather jackets, liberty spikes, and edgy melodies. Photography was a way to make sense of an ever-changing world, and consequently, her place in it. “I’ve always considered myself a hybrid artist and photographer,” she tells me. Less interested in nitpicking dates for historical accuracy, she’s “more so concerned with cultural and social dynamics.”

Once the early 90s rolled around, the newspaper Robin worked for went on strike indefinitely. Seeking a new source of inspiration, she discovered one at a park near the United Nations in Manhattan. Protesters were raising awareness about the increasingly bloody territorial conflicts in Yugoslavia, though they’d been scarcely reported on in mainstream American media. Robin approached a group of women who were protesting to learn more, and before long, decided on her next career move. “Some of their stories really touched me,” she says. “After that, I was determined to capture the war.”

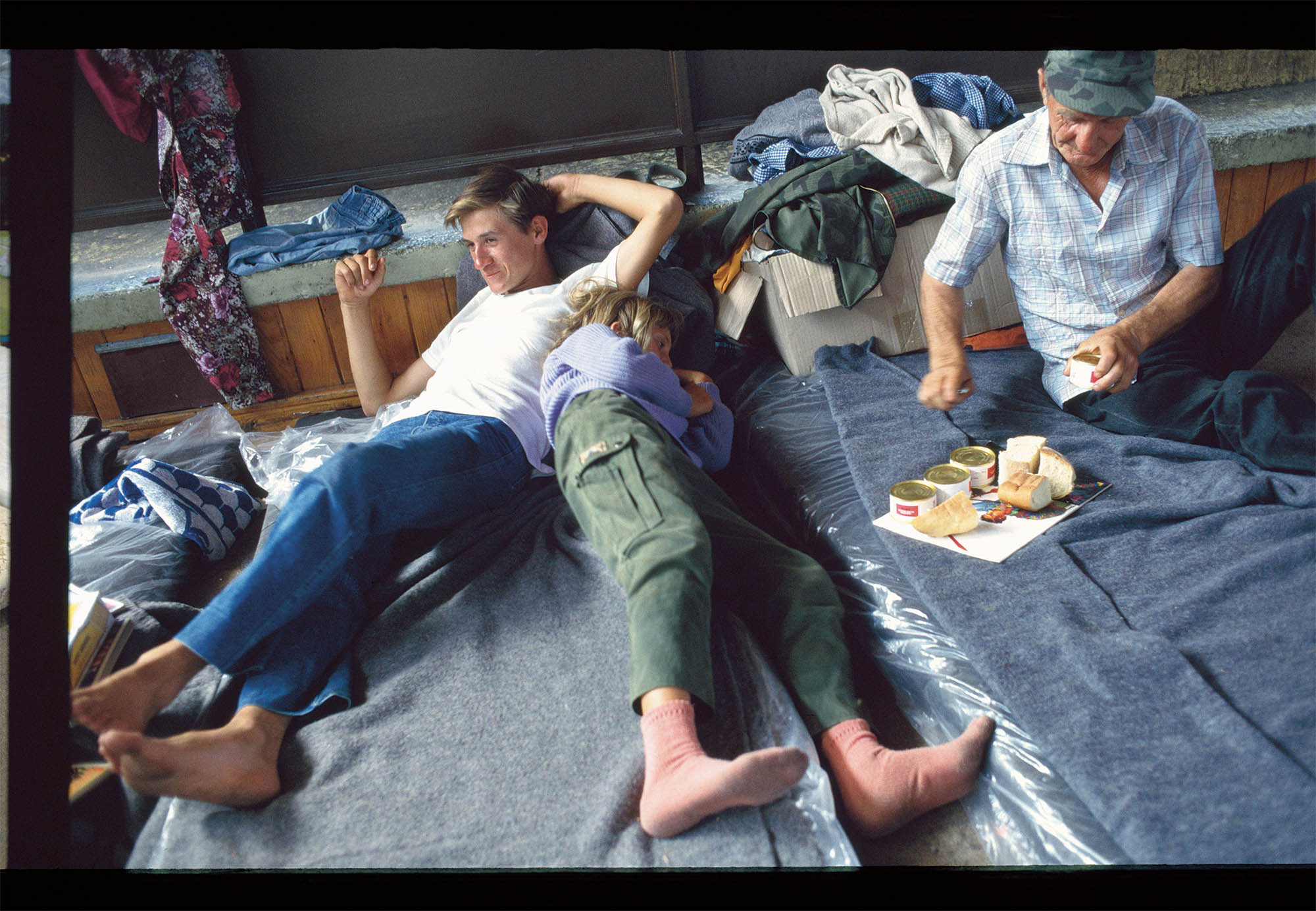

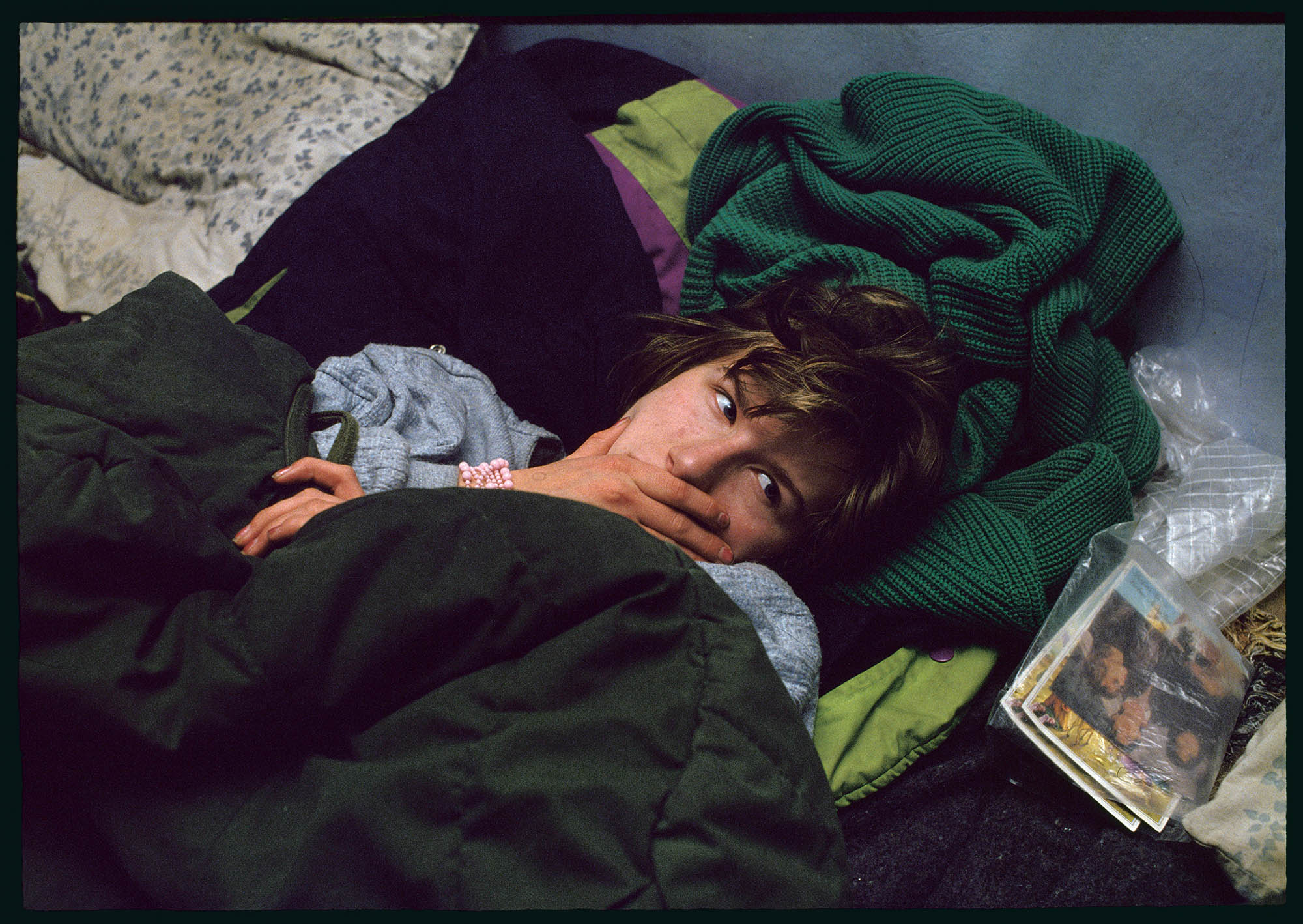

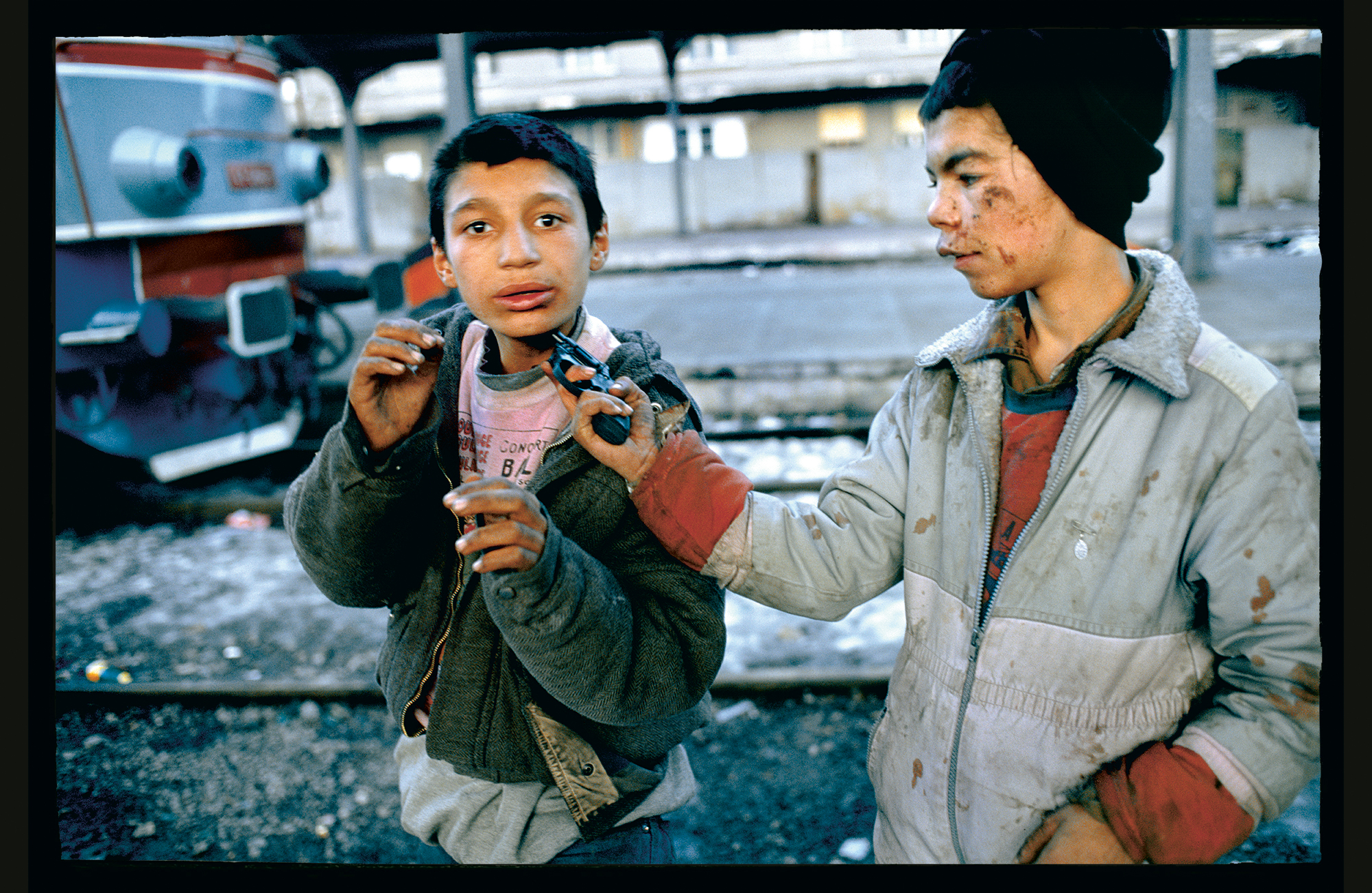

From 1992 to 1996, Robin traveled across former Yugoslavia, Poland, Albania, Bulgaria, and Romania with her camera in tow, photographing the brutality of combat, economic collapse, and the evolution of a post-Communist society following the fall of the USSR. Her niche body of work focused primarily on women and children, specifically the refugees who fled Eastern Europe in the face of mounting ethnic tensions. Road To Nowhere, a monograph released by Loose Joints on April 13th, chronicles Robin’s adventure through a series of 130 unflinching photographs in both black-and-white and color, most of which went unseen for almost 30 years.

After flying first to Prague, Robin passed through Serbia, stopping in a small town for the night before arriving in Belgrade. Hyperinflation had erupted across Yugoslavia by then, causing widespread starvation as grocery prices soared, gas stations closed, and the national currency’s value continued to plummet. “Everything looked pretty bleak. Shops were empty, windows were broken, and people were selling cigarettes on the street,” Robin explains. “My hotel had no lightbulbs. That was my introduction to war.” She didn’t shy away from similar scenes of destitution during the rest of her voyage, capturing dilapidated buildings, emaciated children in orphanages, and civilians suffering from shell shock.

Violence pervaded her trip, especially in Bosnia, where Robin witnessed the beginning of the Bosnian War and the unfathomable atrocities preceding the Bosnian genocide, which was largely fueled by Islamophobia. She recalls walking through Sarajevo with her camera in 1993, attempting to avoid the infamous ‘sniper alley’ and constant shelling attacks. While other reporters had the luxury of armored vehicles, Robin did not. Well-acquainted with the perils of freelance photography, she walked, hitched rides, and picked up odd jobs as she went along, often enlisting the assistance of local high schoolers to translate the language. By her side in Serbia amid all the chaos was her longtime companion Cvetko, whom she met early in her travels and still remembers fondly.

“After we landed, we got a ride in an armored jeep to the Holiday Inn in Sarajevo, which was essentially another front line of the war,” Robin writes in the book. “Heavy shelling went on outside my window every night. I crouched on the floor of my hotel room, thinking it would protect me. Somehow it did.”

This fusion of autobiographical and archival elements gives Road To Nowhere the feeling of an intimate photo diary. While her precise timeline remains a tad hazy, every image evokes vivid memories for Robin, like when she saw frontline soldiers casually throwing up peace signs in Grbavica, a residential quarter on the Serbian side of the border. “I felt like I was taking pictures of kids in Times Square,” she says. “These were supposed to be the deadliest soldiers in the war.” Another striking photo captures the calm before the storm: a group of young Muslim soldiers in the middle of target practice, smiling widely as if to pose for a class picture. In July 1995, about a year after Robin left Sarajevo, Bosnian Serb forces massacred over 8,000 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica, a small mountain town near the city.

Several of Robin’s photos also document emerging youth subcultures, providing a bit of positivity during dark times. Her camera occasionally led her to unexpected moments of camaraderie: teenagers in baggy clothes playing arcade games together, rowdy house guests dancing on tables, or lovers kissing passionately in the street. Once, as Robin roamed around Belgrade, she randomly noticed a poster advertising an all-night rock concert and chose to attend on a whim. Euphoric partygoers raged until the early morning hours, rising from the ashes to create a temporary oasis of optimism, unity, and bliss.

As for the book’s ambiguous title, Robin doesn’t remember the exact inspiration for Road To Nowhere — only that she was listening to Cat Stevens when the idea occurred to her. “It means different things to me at different moments,” she says. “I definitely left it up for interpretation.” Maybe it’s a pessimistic metaphor for the cycle of violence she observed throughout Eastern Europe, given how her photos hold more emotional weight in light of Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine. Or, we can choose to read the name as a tribute to those refugees who were brave enough to escape, hoping that even the road to nowhere was worth the risk.

Road To Nowhere, published by Loose Joints, is out now.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on culture and photography.