Steeped in legend, history, and myth, the destruction and neglect of 1970s New York gave way to an unparalleled cultural renaissance. While the Concorde soared overhead, ferrying 100 of the world’s most dazzling jet-setters across the pond, New York was plummeting into economic catastrophe, barreling towards bankruptcy at the speed of sound. Although down, New York was far from out. Nature, abhorring a vacuum, inspired creativity, the likes of which had never been seen before or since — with the rise of punk, hip hop, salsa, and disco coming straight out of working-class communities.

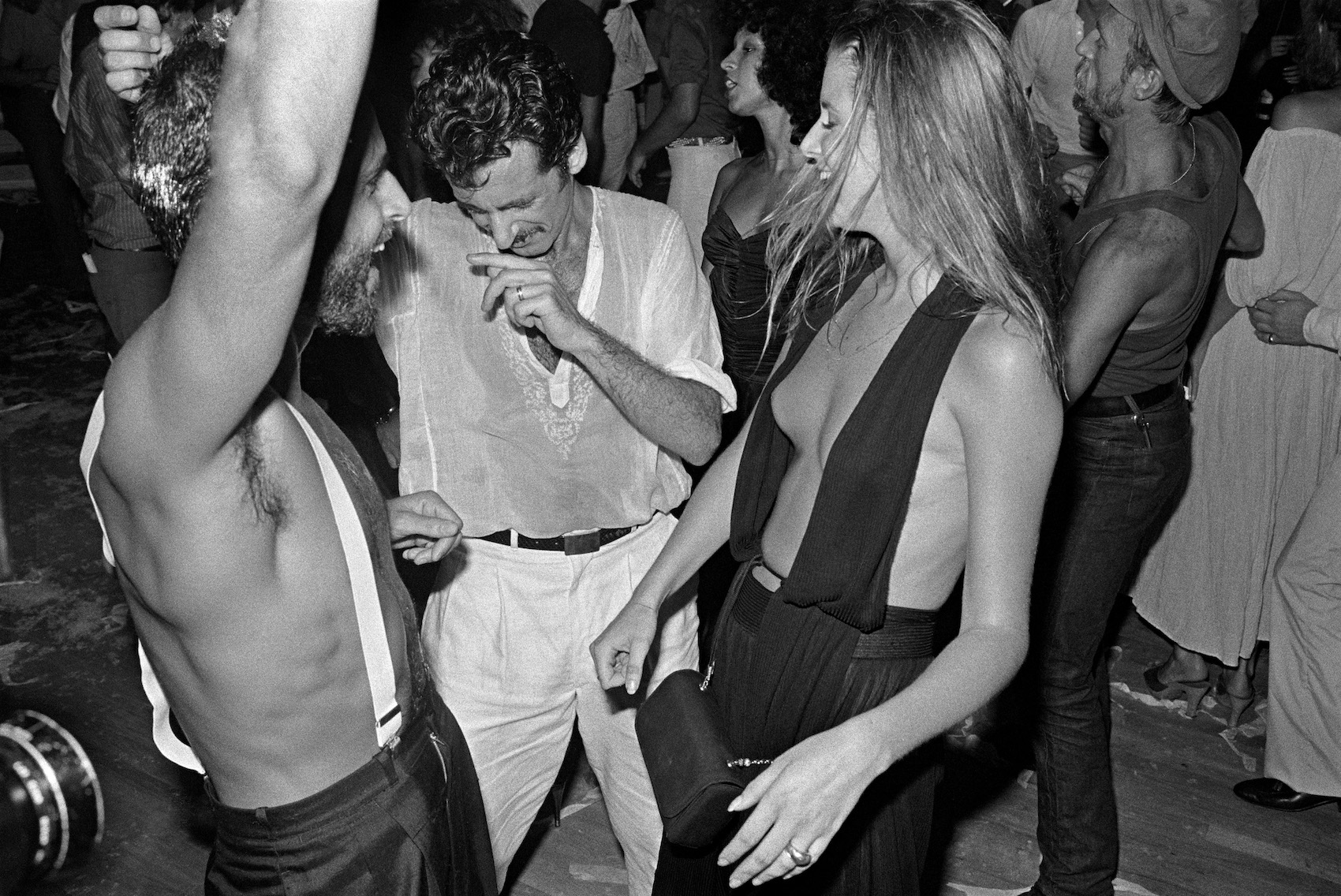

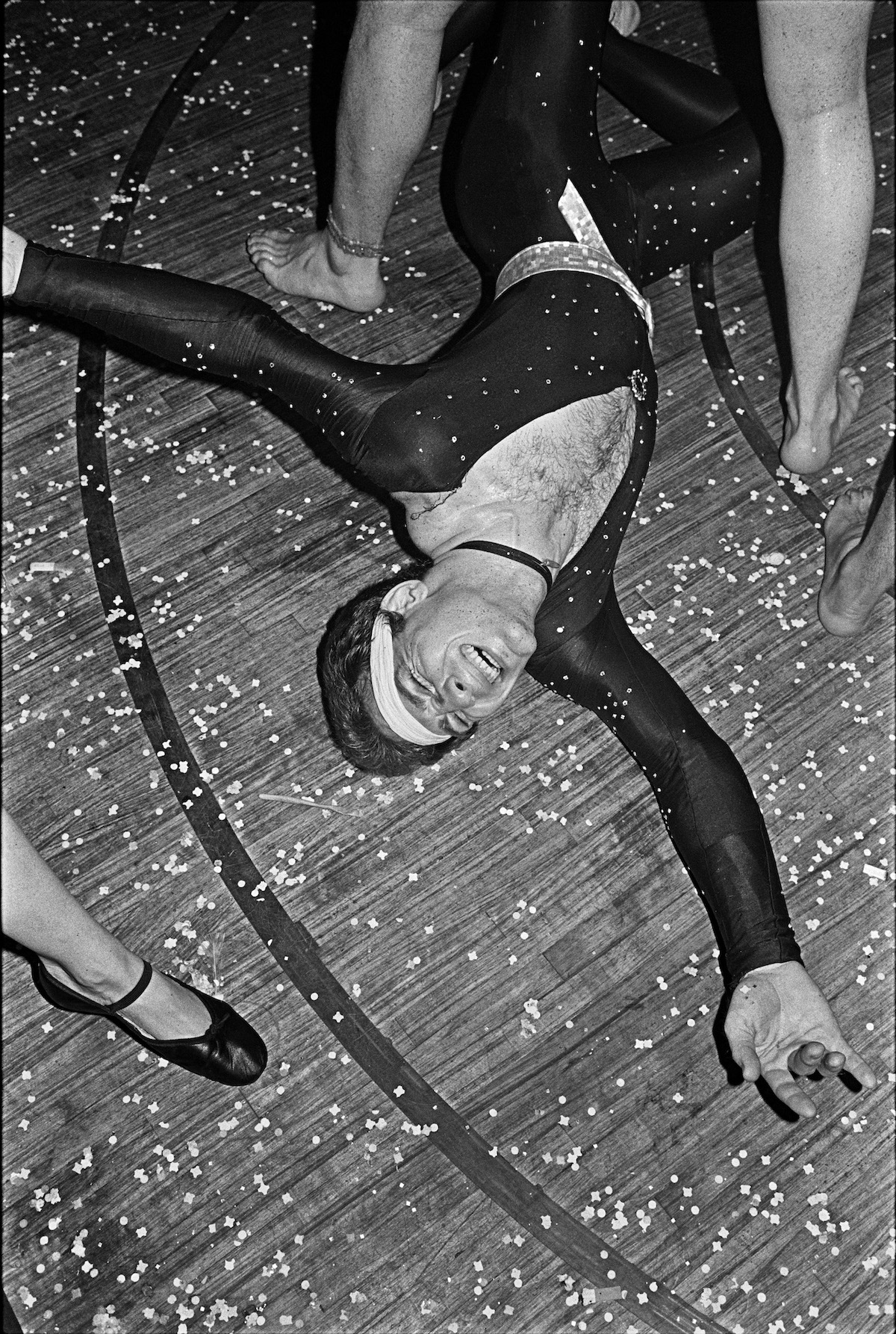

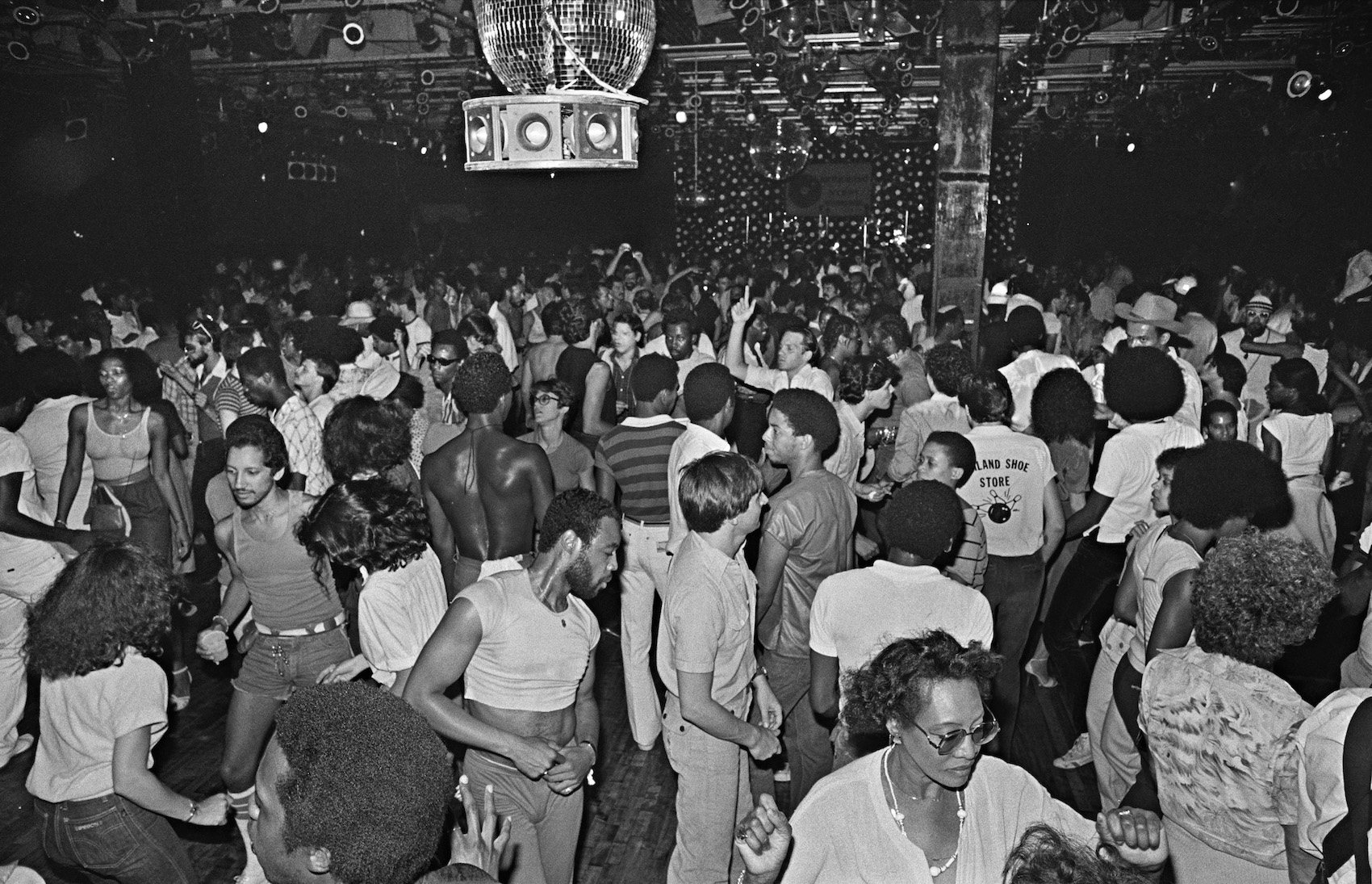

With the provenance of predominantly Black, Latino, and Italian gay men, disco spread like wildfire throughout the city’s sizzling nightclub scene with its high energy, four-on-the-floor beats, orchestral harmonies, syncopated basslines, and foot-stomping diva vocalists. Emerging in the early 1970s, disco became the sound of a new generation coming of age during the Sexual Revolution, Civil Rights, Gay Liberation, and Women’s Liberation Movements — creating a post-hippie utopia that was as influential as it was short-lived. Embracing the ethos of “live and let live,” disco was the anthem of survivors, radicals, and renegades who wanted nothing more than free expression on the dance floor.

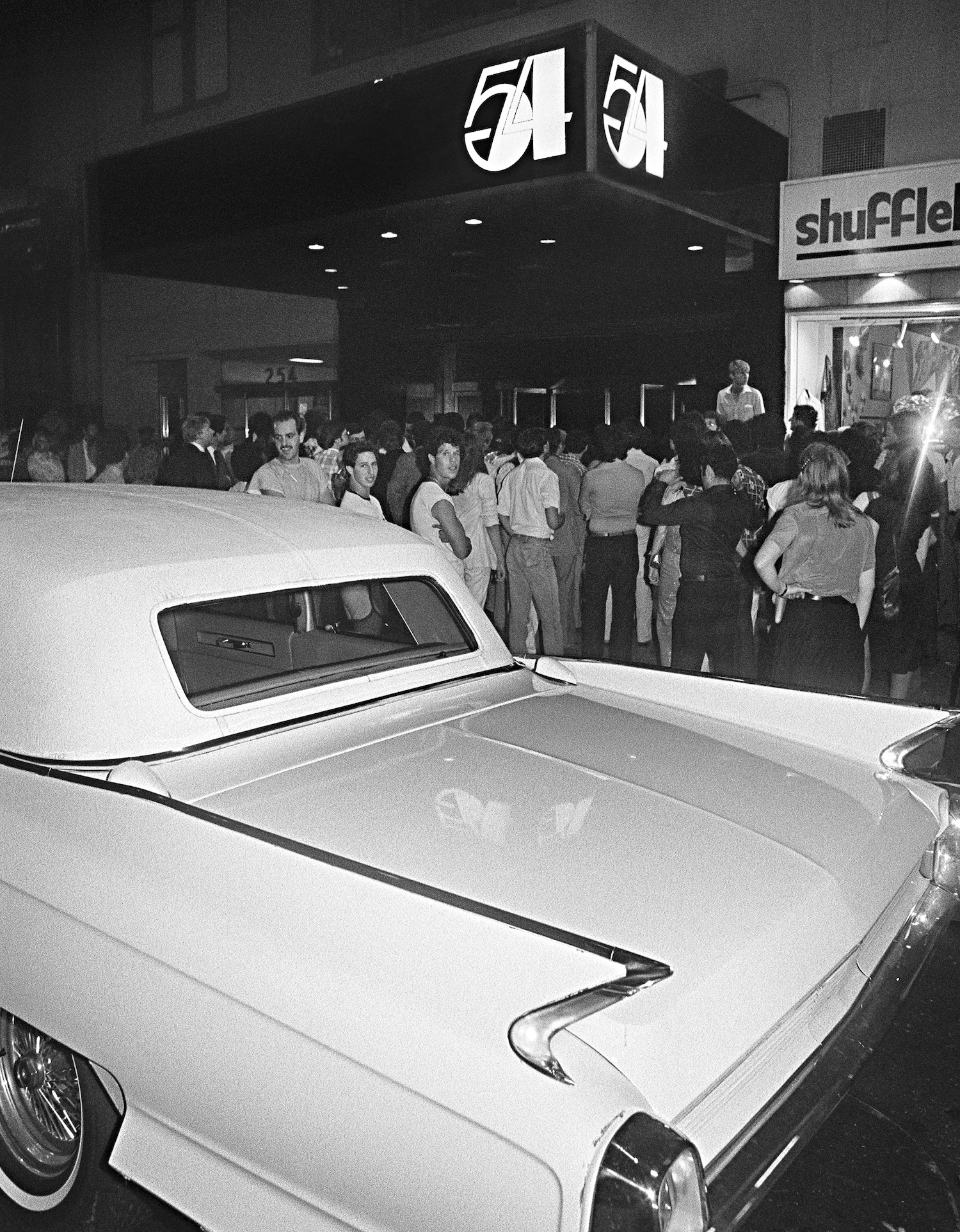

Although photographer Bill Bernstein was a rock and roll fan, he became increasingly curious about the disco scene after Studio 54 opened on 26 April, 1977. College buddies Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager transformed a former CBS television studio on West 55th Street into the world’s most exclusive den of iniquity. Hollywood stars, musicians, artists, models, fashion designers, artists, street legends and socialites flocked in droves, sailing past hundreds of wannabe revellers standing for hours behind the velvet ropes. Bill wanted to see what all the fuss was about — but he couldn’t get in until he got the call from his editor at the Village Voice. Would he shoot a dinner party honouring Lillian Carter, mother of then-President Jimmy Carter, at Studio 54? You bet he would.

“I was amazed when I walked in,” Bill recalls. “Here was this place with a crazy reputation as a hedonistic playground, and when I got there it was older people in tuxedos. There were tables on the dance floor. They had a fashion show. There were so many photographers; they followed people around in a group, climbing over each other for the picture.”

Bill spotted Andy Warhol sitting next to Lillian Carter, engaged in a conversation — the perfect scene to illustrate this unlikely event. “That’s the shot I got for the Voice. I would have love to listen to these two grey-haired people from two different backgrounds talking to each other,” he says.

As the event came to a close, Bill realised the opportunity at hand. He bought 10 rolls of film from a photographer, went up to the balcony, and hid in the shadows for an hour as the staff cleared out the tables and set up for the evening. The doors opened, and the regulars arrived, ready to trip the light fantastic. Bill descended to the dancefloor and was blown away by the highly theatrical setting replete with magnificent lights, a magical sound system, and extravagant décor.

One of his first photographs that night was of a man and woman dressed like Marlene Dietrich in Morocco, which appears on the cover of Disco (Reel Art Press). The tuxedo-clad couple had all of the glamour and none of the stodginess of the black-tie dinner party. In that moment, Bill understood there was more to the disco scene than met the eye. “They reminded me of the movie, Cabaret, and the Weimar Republic in Berlin where the rich aristocracy met underground culture in nightclubs — and then above ground, there was a war-torn city,’ Bill says. “I started to feel a connection to that period of time where all these cultures were coming together and partying in the ruins of New York City.”

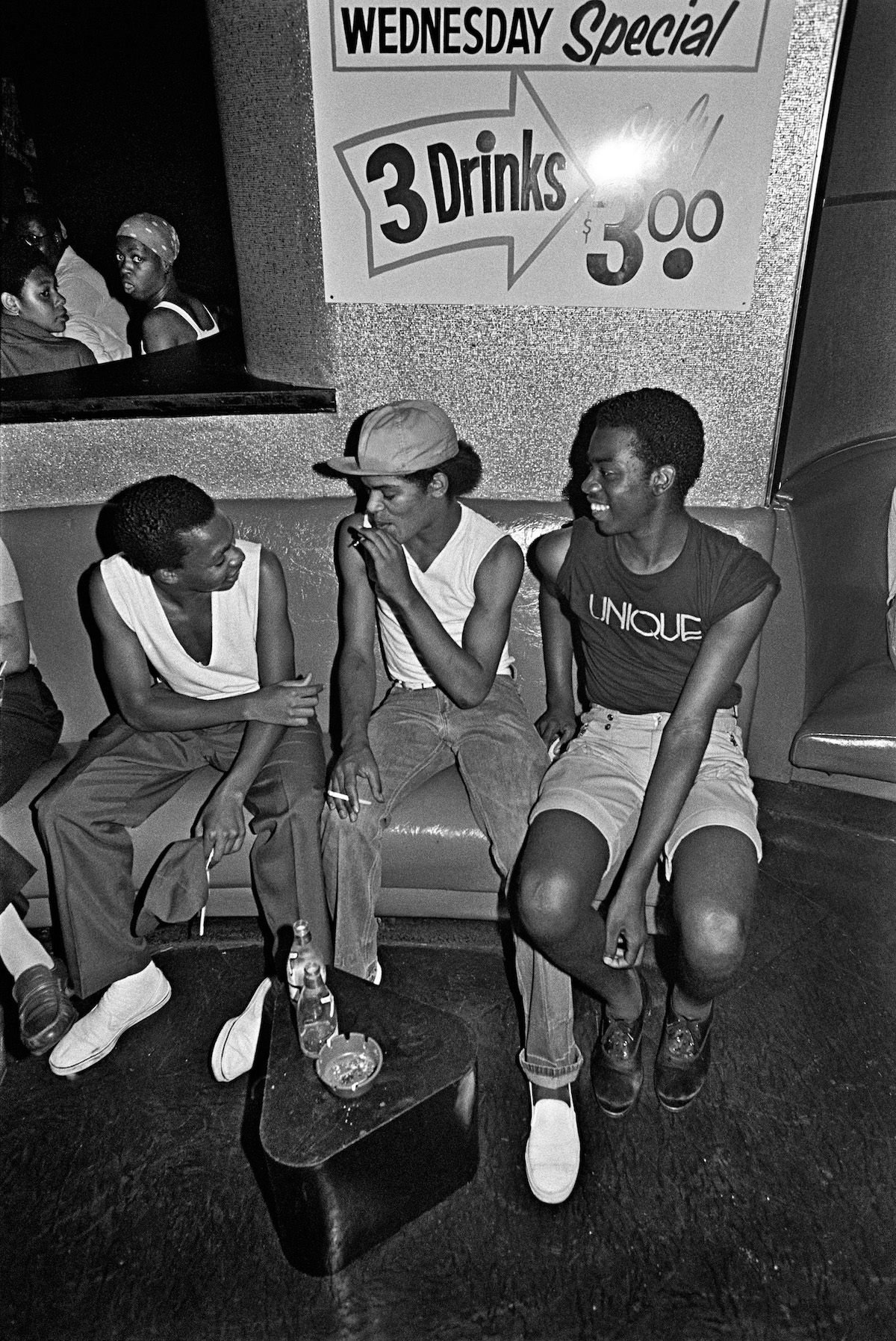

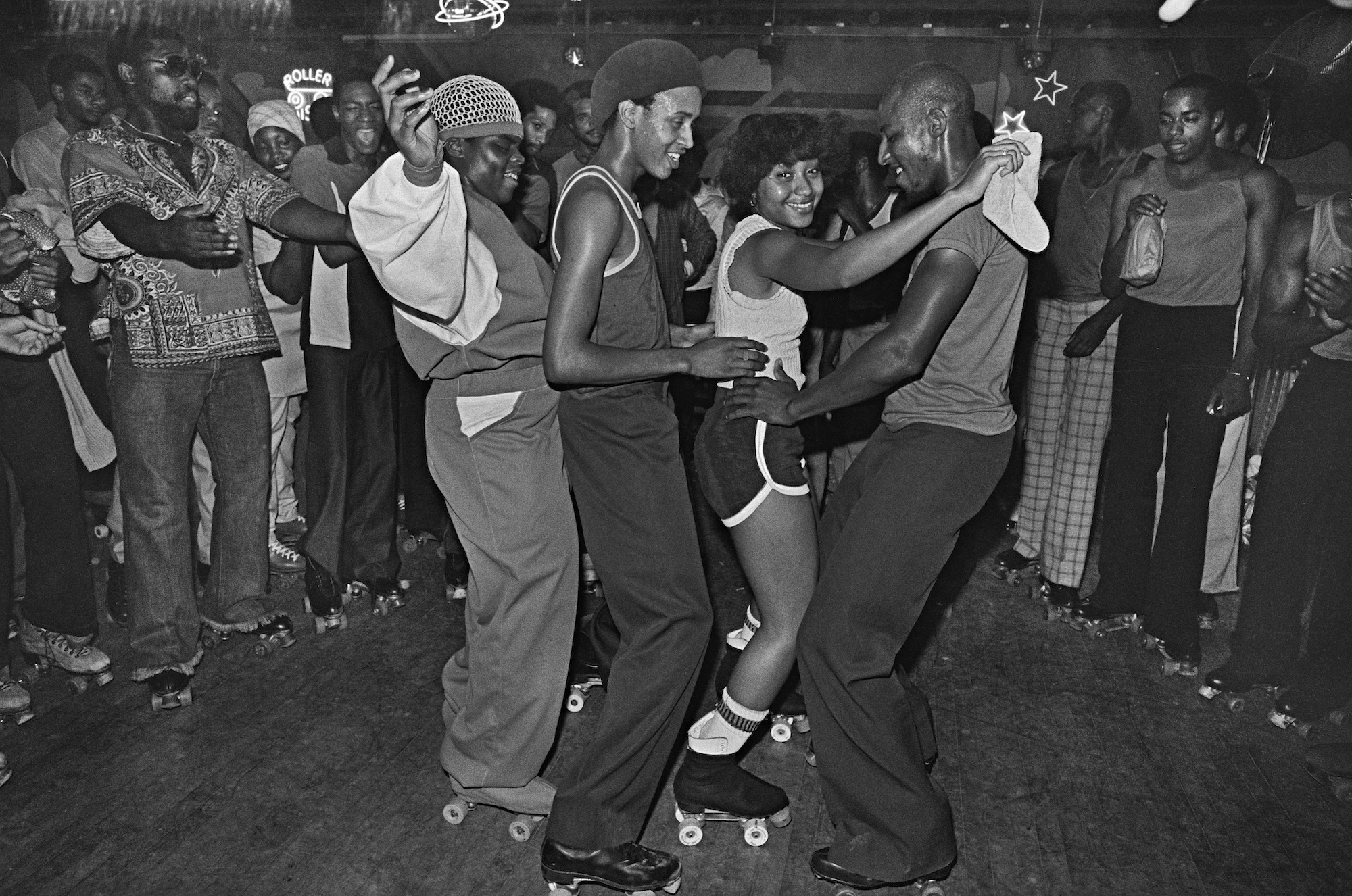

Intrigued, Bill started hitting up all the hot spots, trooping out to Brooklyn to check out Empire Roller Disco, Better Days, hitting up Paradise Garage to see Larry Levan spin, and heading down to Tribeca for the Mudd Club, the city’s “anti-disco” nightclub. “A lot of clubs were popping up at that time. New York City was in default, and rents were really cheap, which drew a lot of creative people to the city.” Bill moved to Soho in 1972, soon after the neighbourhood was given its chic portmanteau. “Then, in 1977, Saturday Night Fever hit the scene, and all of a sudden, disco was in the air. It was a movement.”

Bill quickly amassed a singular body of work capturing the magic and majesty of the disco scene. Now, a selection of his photographs will be on view in the new Glitterbox exhibition Last Dance: Bill Bernstein’s Iconic Photographs at the End of the Disco Era, opening 19 April at Defected Records in London, and in a book of the same name, which includes a foreword by Honey Dijon.

Bill’s photographs offer a window into a world that represents the pinnacle of 20th century American culture. “There was a freedom of expression and inclusion,” Bill says. “You could be whoever you wanted to be — and you were welcome here. It was a party, and everyone was invited, and I think that’s what people yearn for — to be accepted. The disco satisfied that need pretty well.”

Inspired, Bill teamed up with a writer to create a guide to the New York disco scene called Night Dancing. Random House published it in 1980 — “just when disco died,” Bill says. “Between the AIDS crisis, Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager going to jail [for tax evasion], and the Disco Demolition in Chicago, there was all this backlash against disco, which was becoming overly commercialised. When Ronald Reagan came to power, there was a conservative backlash. Disco was queer culture, and it was pushed underground. But the party spirit lives on through spaces like Glitterbox, which is all about inclusion.”

From the outset of his photography career, Bill understood that photography could build bridges between worlds. Adopting the eye of an anthropologist engaged with people in the scene, Bill looked to the work of Diane Arbus for inspiration. “When I was photographing at GG’s Barnum Room, which was a transgender club, I had a lot of her imagery in mind,” Bill says. “She wanted to create portraits of them as people, and that’s how I felt. I wanted to get an honest look at what was going on. But I wasn’t analysing it as I was going along. I was shooting it because it was a story I wanted to tell. I didn’t see the significance of that time period until much later on.”

‘Last Dance: Bill Bernstein’s Iconic Photographs at the End of the Disco Era‘, presented by Glitterbox, is on view 19–29 April, 2022 at Defected Records in London. Buy the book and limited edition merch here.

Credits

All images courtesy Bill Bernstein