Pierre René-Worms started out as neither an aficionado of music nor of photography, yet he managed to carve out a niche for himself in both spheres. In his late teens, the self-taught French photographer bought the book L’Aristocratie du Reportage Photographique and looked to Norman Seeff and Jean-Loup Sieff for inspiration. He kept a close eye on the development of the post-punk and New Wave scenes, tracking bands that were wholly unknown in France and only just burgeoning overseas — like Joy Division and Soft Cell — many of whom went on to become legendary. And throughout the late 70s and early 80s, Pierre photographed everyone from minor Scottish rockabilly bands to Duran Duran on a yacht in Saint Tropez, publishing his spectrum of work in the local French press.

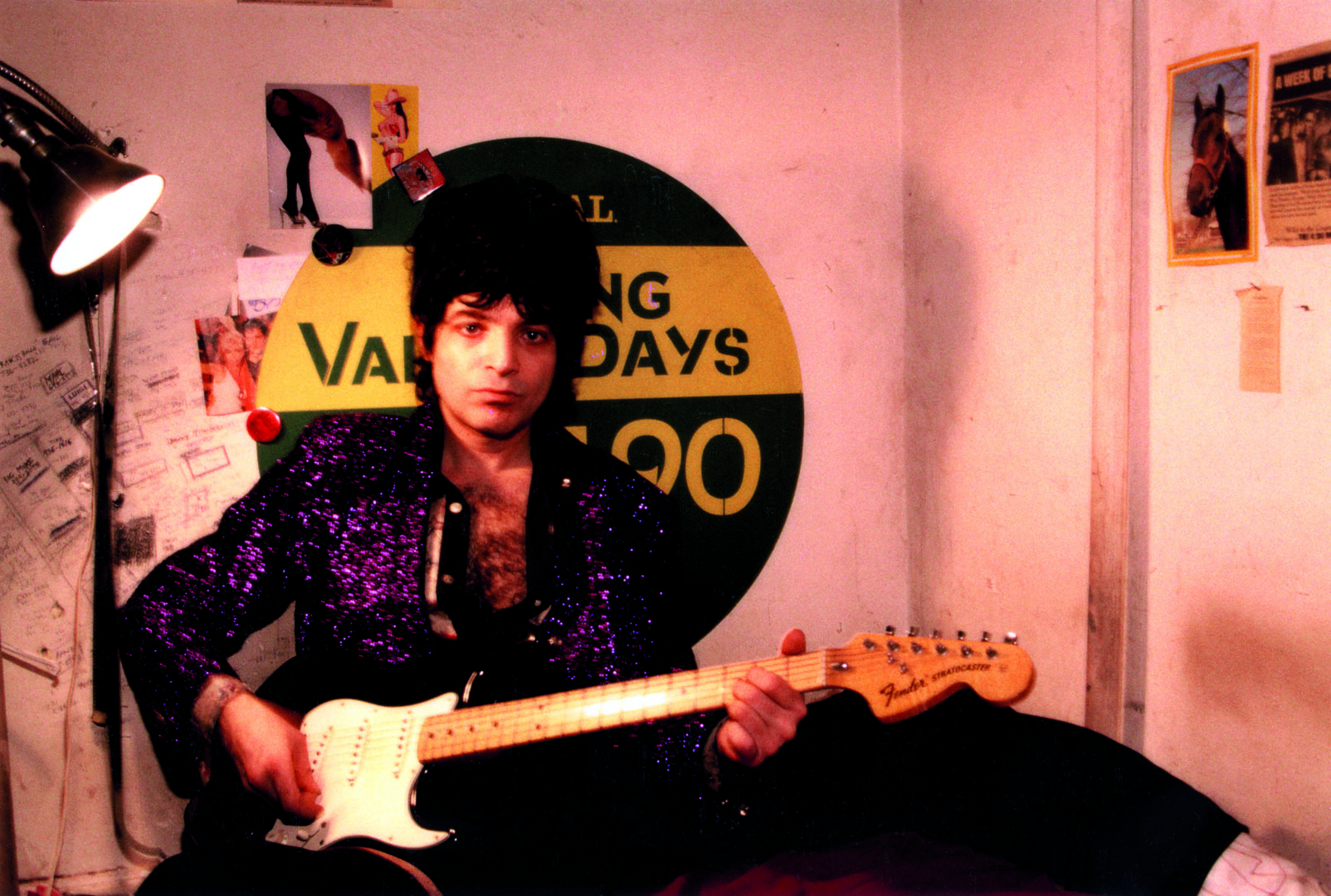

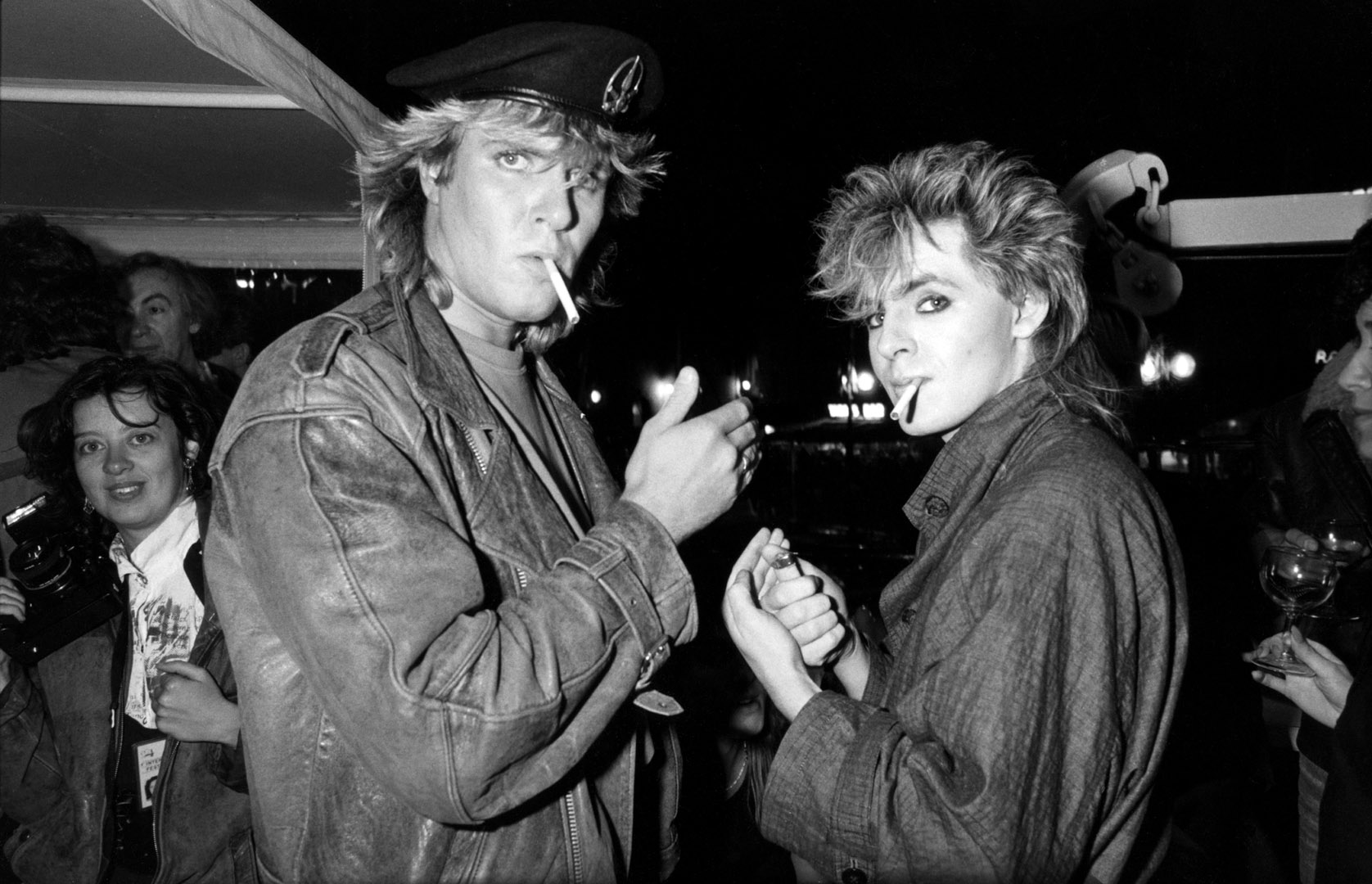

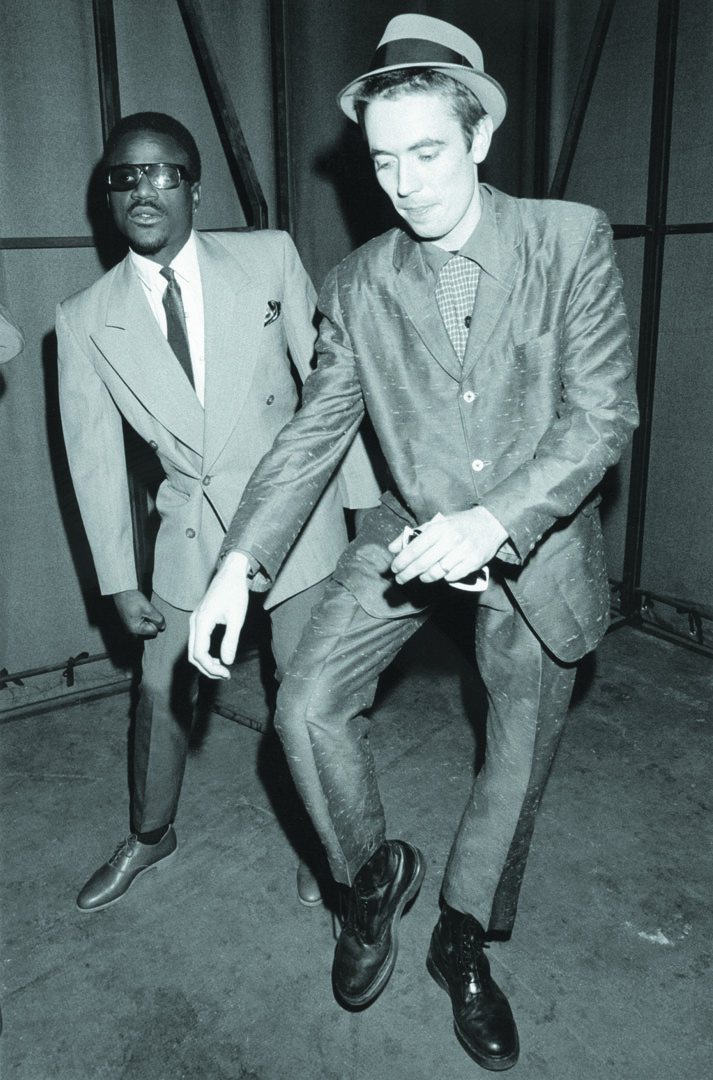

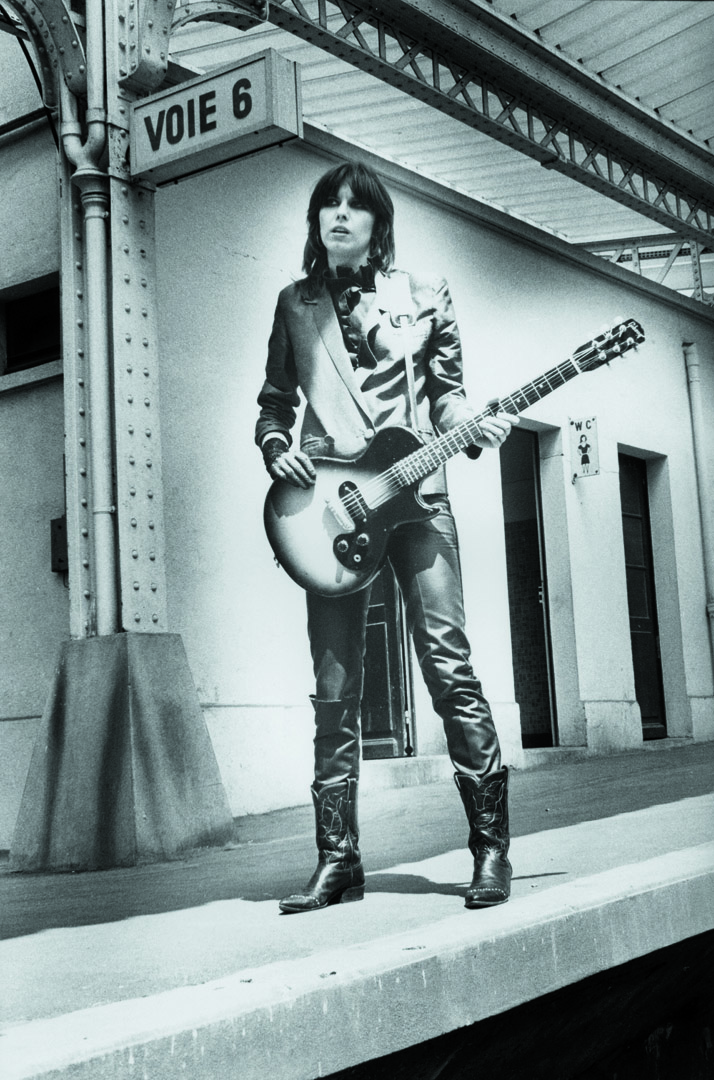

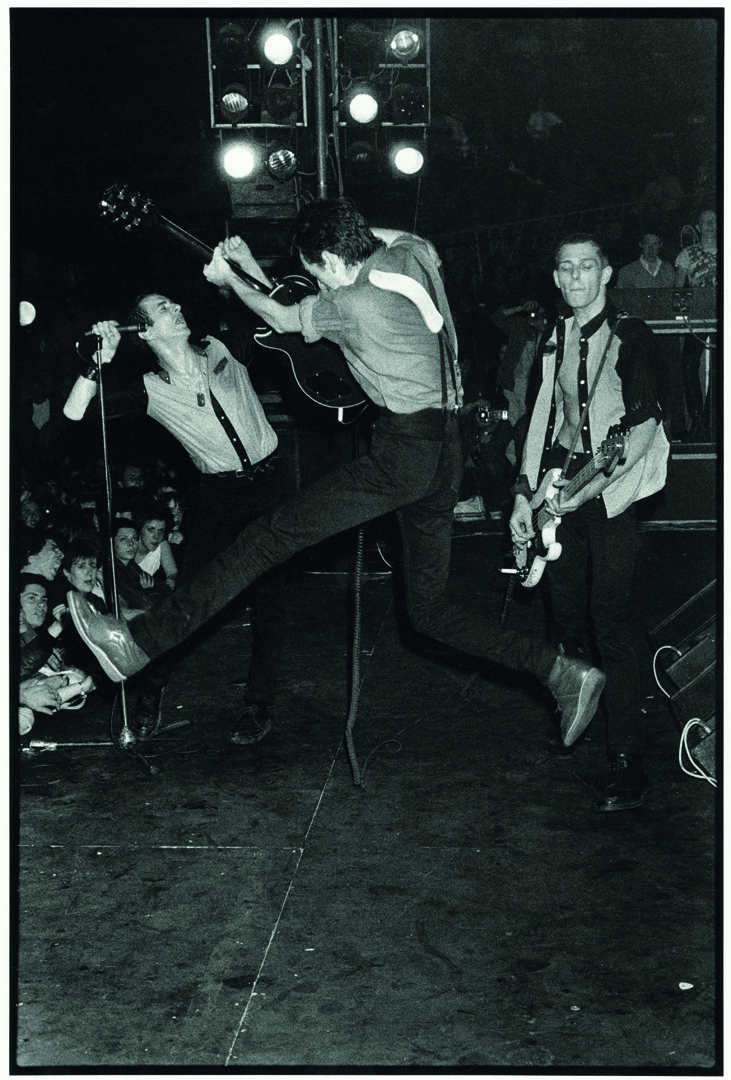

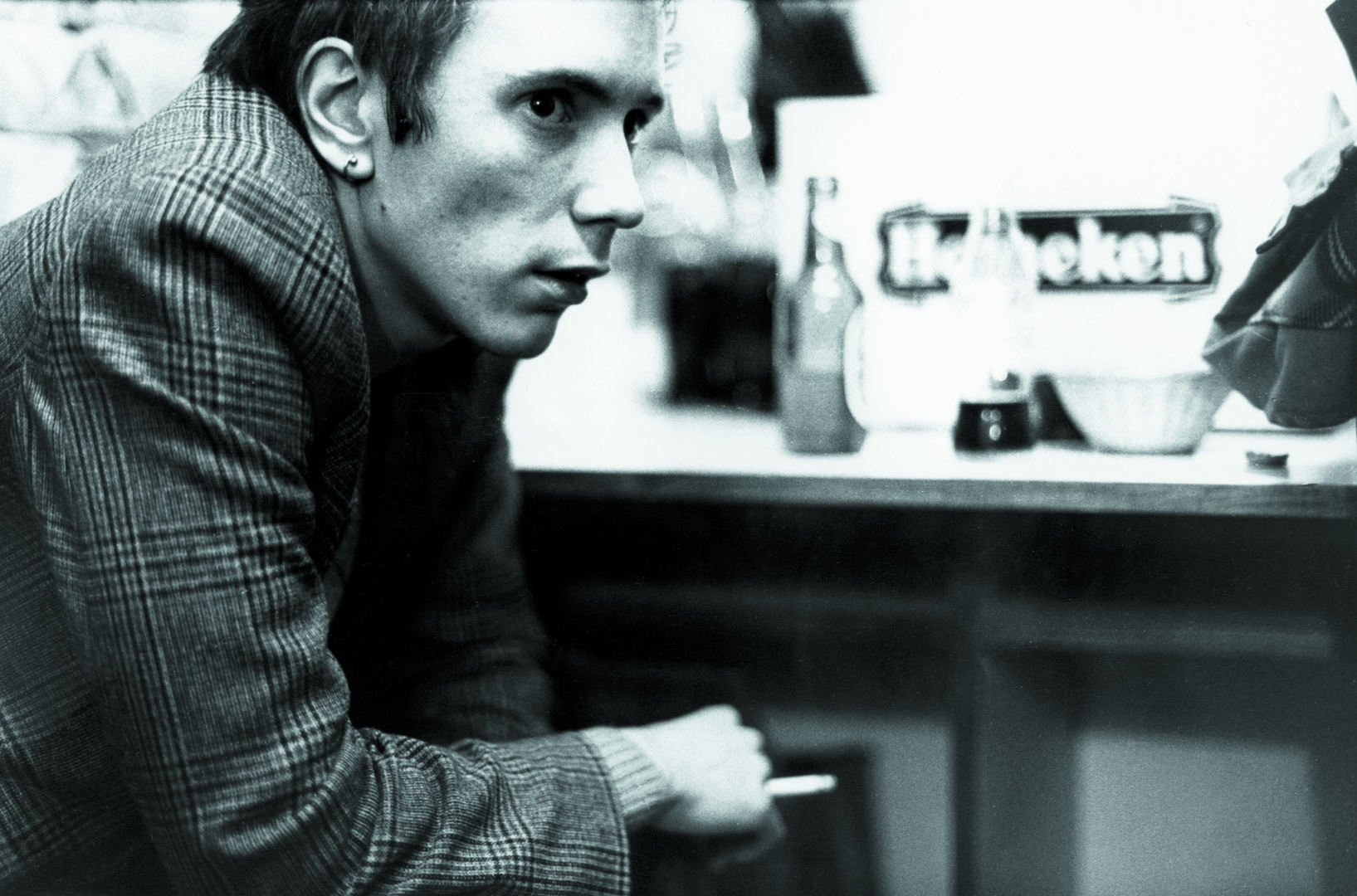

Pierre’s style of photography leaned on a documentary approach while striving for studio-quality portraiture. The result was an analogue eye on a music scene that was still loose, wild and informal, without meddling publicists or overwrought stylists creating hurdles to access and authenticity. Given how today’s bands so readily cite earlier generations of musicians as touchstones, the iconography from decades prior is also drawn back into the spotlight.

A selection of Pierre’s photos are featured in the new exhibition Patrouille de Nuit (Night Patrol), at Confort Moderne in Poitiers, France, which includes nearly 300 of his black and white and color images. International bands (Marianne Faithfull, The Cure, The B-52’s) appear alongside local French outfits (Taxi Girl, Etienne Daho, Les Rita Mitsouko), all of whom took off in the late 70s and early 80s.

Ahead of the opening, we spoke to Pierre, who today heads up the photo department for France Media Monde, about using Paris as a playground, the longevity of certain music references and the inimitable Grace Jones.

Were you commissioned to cover what was up-and-coming? Or were you scouting the emerging bands yourself?

I did it myself: I took the temperature of what was going on by reading the English press. My barometer was the news-in-brief in the magazines NME and Melody Maker. It was about finding new bands, listening to what they did and when they came to France — or sometimes I went abroad — I got in touch with them and worked with them. There was very little room in the French press at the time to depict these types of acts. But the idea was to spot music trends, to act as a pioneer and precursor. Today we’d call that creating buzz. Being a photojournalist then was like being an influencer now. It was about getting people to talk about the new — at the risk of making mistakes! Some groups stayed unknown. But many of them grew into blockbuster acts.

How much were you aware of how other photographers were already depicting these groups?

I had very little info, visually speaking, ahead of time. There were fewer images circulating then. Especially for emerging bands, they were only briefly mentioned and without visual accompaniment. The main visual access was the album cover or the cover of the single. It wasn’t like today, with the documentation of every look, where you can see what has already been done by the band or by photographers. During that epoch — and it was an epoch, it was 40 years ago — we were constantly in ‘discovery’ mode. The band’s look was included in this discovery; it was important to the public imagination surrounding rock music.

What mix of spontaneity versus planning was required for successful shoots?

My work is that of a photojournalist, rather than a studio photographer. I’ve worked with artists in a studio setting before and things are much more considered in that context. Whereas I adapted in the moment relative to the light and the setting, which you can’t master the way you can in a studio. Portraits are a kind of reportage. Every time was different; every time was an adventure. There are no rules.

After selecting the band, it’s a question of gaining their trust. First it’s an interpersonal encounter, then it’s about creating an image. It’s important not to have preconceived ideas. You need to spend time with the band — so they forget that you’re there. If you’re too present, you disturb them. This photojournalistic approach was rarer in France than in the US or the UK at the time, the way Bob Gruen and Annie Leibovitz were photographing for Rolling Stone.

Since you so often used Paris as a backdrop, how do the images reflect it as a place?

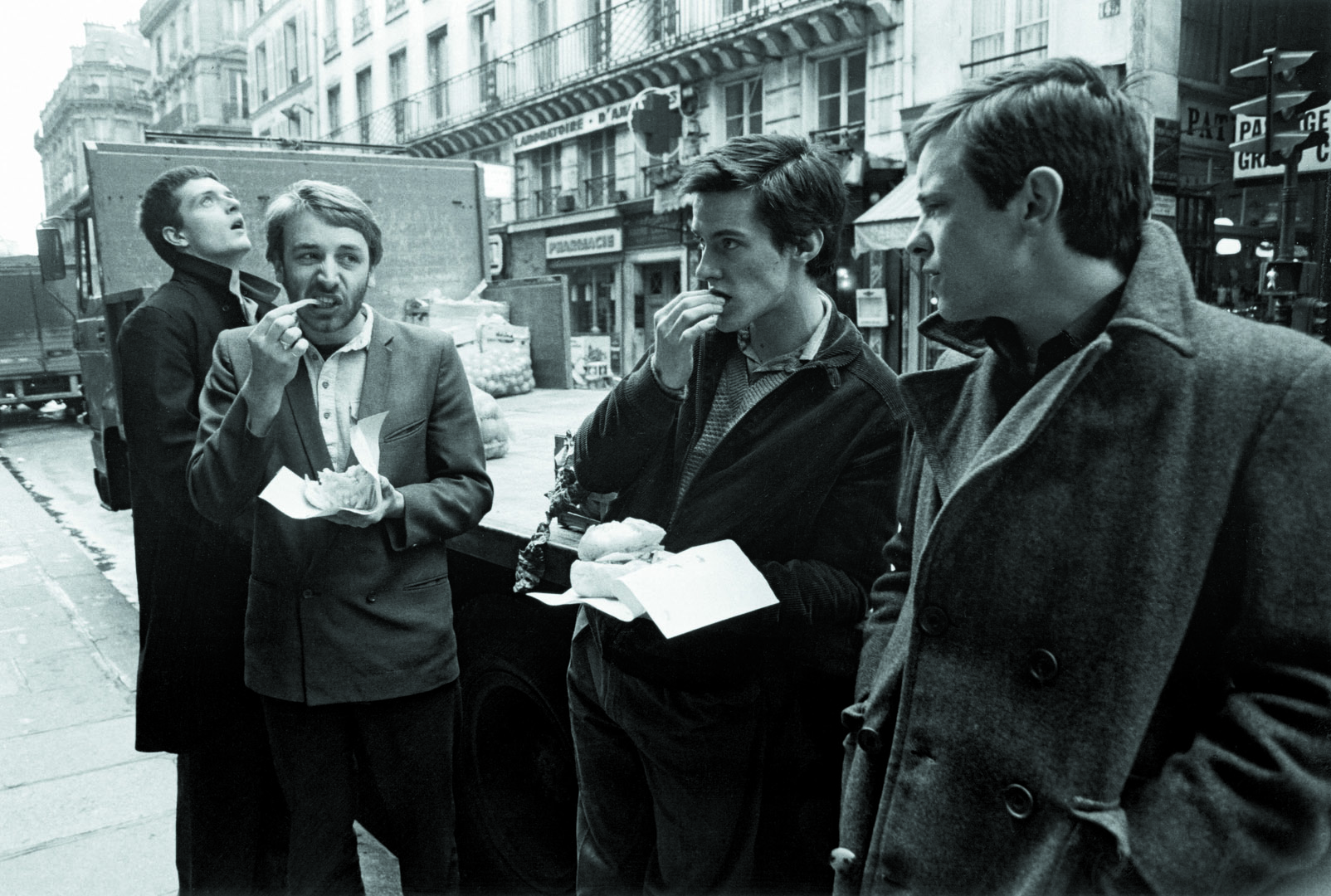

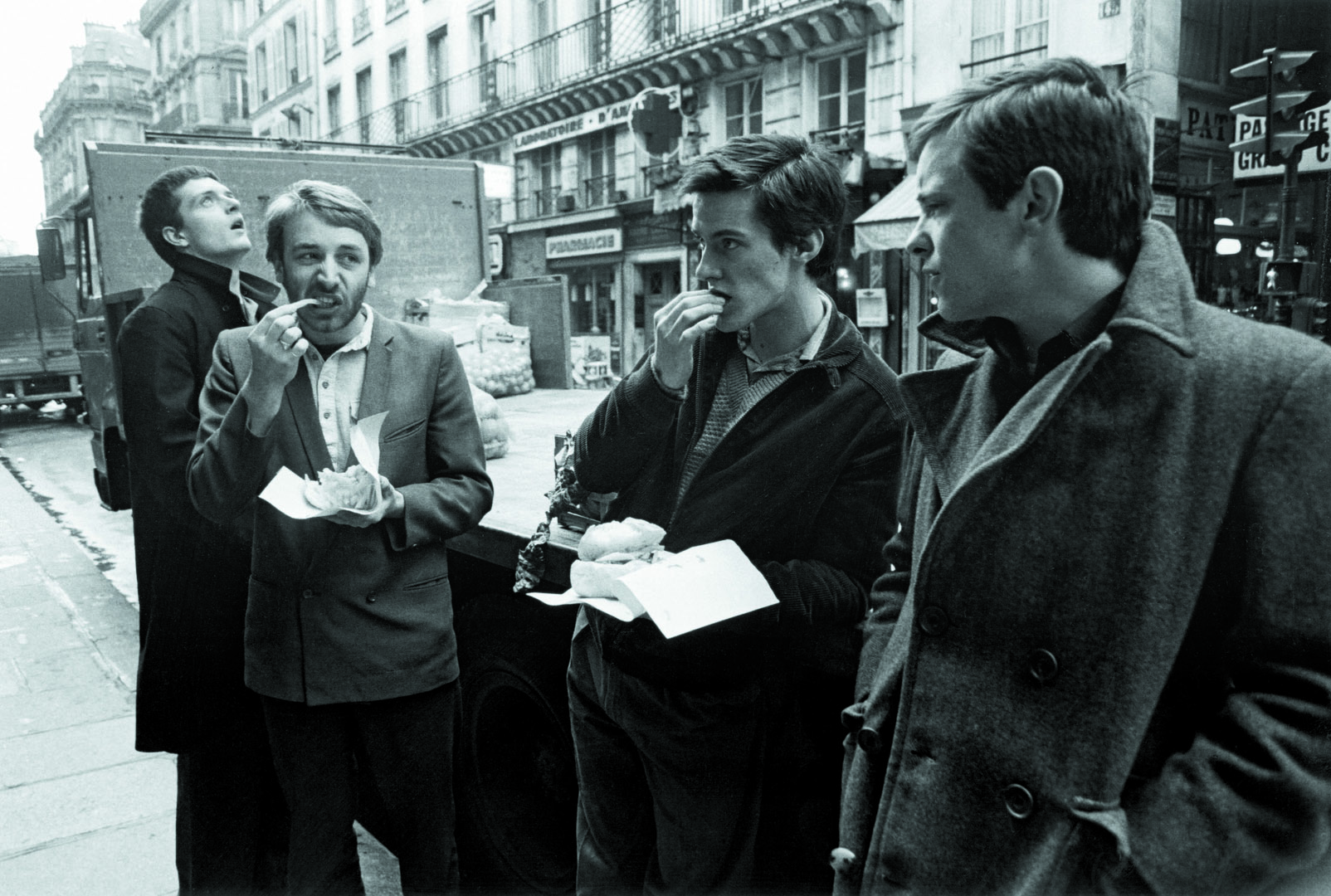

It was nice to walk around with subjects and have them discover the city, which they didn’t know well, and do shoots in different spots. With The Cure, we took photos at night, underground; with Joy Division, we wandered around Les Halles, which was under construction at the time. It’s about mixing the world of the band with the city they’re visiting. I also photographed bands in New York, in London, in Berlin — or where they lived. The idea is always to work with what already exists around you. It’s about living alongside the musicians and adapting to their lifestyle and who they are, to create images that are ultimately personal to them.

Why call it Patrouille de nuit (Night Patrol)?

The phrase comes from a reportage I’d done for a weekly paper that no longer exists. It was about a policeman who sang on the weekends in the banlieue. We trailed him at night when he was working in different neighborhoods as a policeman, and on the weekend we followed him as a performer, wearing a sequined suit and bowtie accompanied by half-naked dancers on stage. It was a little wink to that, but also of course it references gigs at night. To spot new talent, you patrol different concerts at different venues as a night owl who works and lives most fully when it gets dark.

I love the image of Grace Jones. Can you talk about the shoot with her?

I photographed her in a hotel lobby on rue Christine in Saint Germain, around 1981-82. She had become known in France because she did an Edith Piaf cover, but this was before she was the face of the bicentennial of the French Revolution, in a parade choreographed by Jean-Paul Goude on the Champs Elysées in 1989. She was known within the music scene, but she wasn’t a global star the way she would later be. I had an hour with her, and towards the end I asked her what she herself listened to music on. She had these unappealing headphones, but then she said: ‘I have this boombox.’ She went up to her room to get it and then came back down. Today, her look is so modern, but this music equipment — which was very modern then — is now so old-fashioned. It’s interesting to see how an image can evolve, in terms of what it represents, across different timeframes. That’s the life of an image: it means different things at different moments.

Do you think these images have resonance today because music is so linked to nostalgia?

It’s true these bands represent a particular epoch that has value today. For each generation, the period you live through is the period you reference. For me, in the early 80s, it was bands from the 50s and 60s that provided that reference. You document music that reflects your current time, that reflects your generation. I’m proud that I took these photos that were pertinent 40 years ago — and that they still are, 40 years later. They transmit something about the era. The gaze changes, because times change. But you have to be lucky, and make good choices.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more music photography.