As the critic Ben Walters once wrote, the queer archive is “fragile from fear and forgetting, too often written in whispers and saved in scraps”. The group show EXPOSÉES, on view at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, turns up the volume on those whispers and looks intently at those scraps, examining the legacy of AIDS within art and addressing the stigmas that defined this epidemic.

Amongst the featured artists — ranging from Nan Goldin to Felix González-Torres — are Régis Samba-Kounzi and Julien Devemy, who met in 2000 at the French chapter of ACT UP, the American grassroots political coalition formed to fight AIDS. Formerly a couple, they still co-parent their teenage son and have both been passionate activists throughout their lives. Julien grew up in a Parisian banlieue and dropped out of art school because he felt activism was a more pressing calling. For the French chapter of ACT UP, he “took photos for archival purposes — not even when anything big was going on, but just to have documents for ourselves”. Régis, who grew up in Congo, has been a militant activist since age 19. AIDS affected his family and the community he grew up in directly, with his mother nursing those who fell sick. When he moved to France, Régis turned to art as a way to raise awareness of the indifference and discrimination faced by people with HIV and AIDS. For the installation at the Palais de Tokyo, Julien’s textile works complement Régis’ photographs.

“I never wanted to be an artist; it didn’t interest me,” says Régis, sitting beside Julien on a Zoom call. But, he notes, “having already intervened on a political and social level, I felt this need to invest in the cause artistically”. In many ways, AIDS broke boundaries between art, activism and documentary: “I wanted to represent people with AIDS, sexual minorities, specifically on the African continent in francophone countries — I wanted to talk about their realities, these people who are the most vulnerable to this epidemic. There were things to say that hadn’t been said.” Régis laments that there hasn’t been anyone akin to South African visual activist Zanele Muholi — who, in fact, has a beautiful show currently on view across town at Paris’s MEP — when it comes to representing queer francophone Africans in art. He was also especially inspired by Greg McNeal, an LA-based photographer who focused his lens on Black men with AIDS.

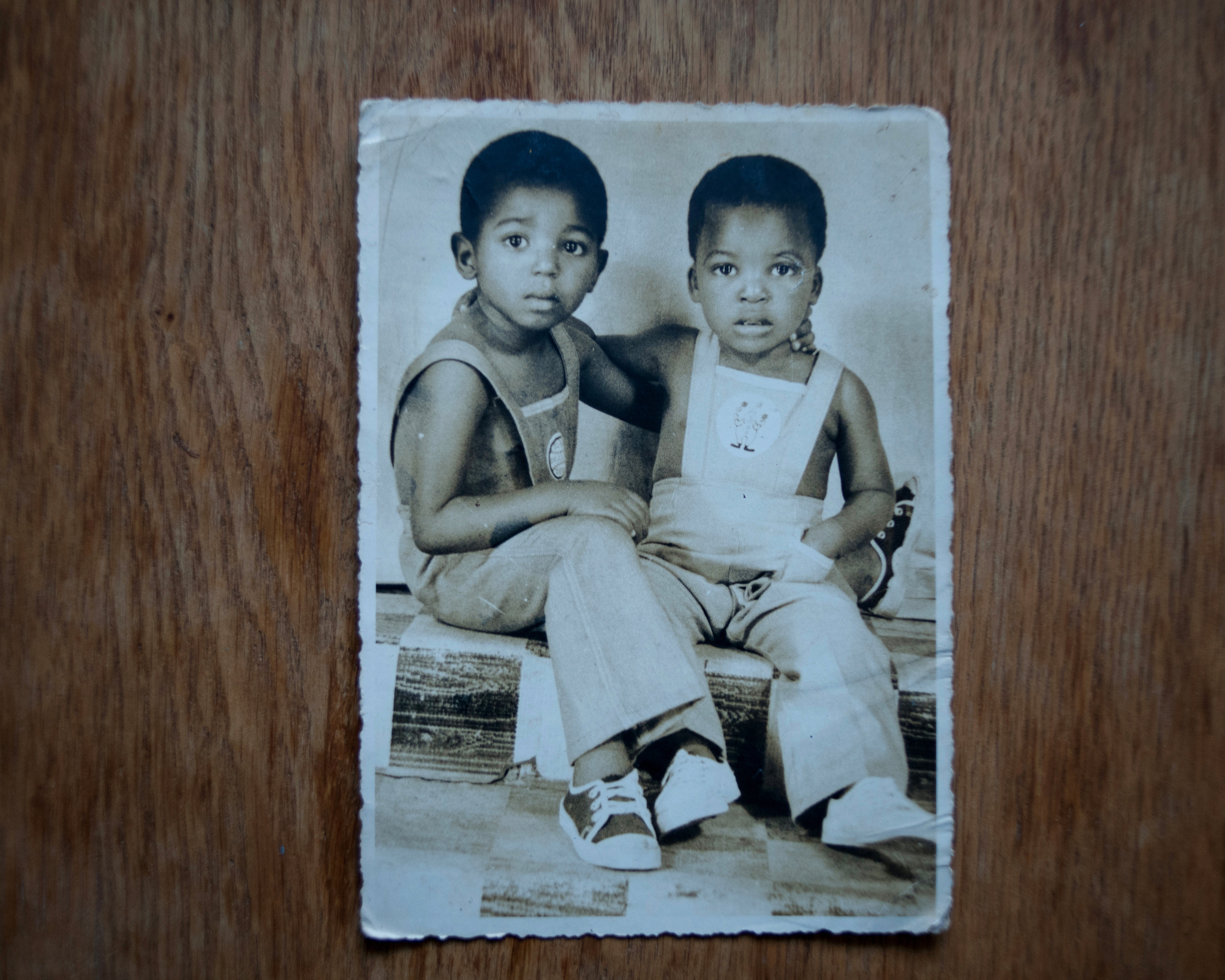

Régis’ photos meanwhile feature trans women standing proudly and gay men embracing each other, of which Julien says he’s “not aestheticising”. With ACT UP, there’s an imperative towards communicating effectively with topical subjects. But with an artistic approach, he can go back and forth between his personal life and the cause; and while he’s not aiming to take beautiful photos per se, he’s not misérabiliste. He shows, despite the despair of AIDS, despite the loss of friends, that there’s still a will towards something joyous. There’s a will to not present his subjects as ‘poor HIV-positive Africans,’ but as people who can be empowered by affirming who they are.

Julien notes that art also functions as a means of educating a new generation who already has the means and access to treatment. “How do we transmit this struggle to them, this story of AIDS, without being the old veterans who lecture on how ‘they didn’t have to live through that’?” he wonders aloud. Both artists emphasise that the fight against AIDS persists, especially outside the West. “AIDS has returned into silence — we think, wrongly, that the epidemic is over,” Régis says. “It’s still urgent in Africa and other countries where access to medication is complicated, and further worsened by the homophobia prevalent in these countries,” Julien adds.

Indeed, making progress sometimes seems impossible: the Pan-African community certainly isn’t free from homophobia and sexism; the LGBTQ community can be permeated by racism; gay men can even express lesbophobia. But the series — entitled “Nos Communautés de Résistance” (“Our Communities of Resistance”) — shows that a certain joy is possible, without muting troubling realities. “We don’t have an answer but we have examples of different lives, how people construct themselves and survive,” says Régis. “To look at these figures is to honour their strength and resilience. The installation, presented on a baby pink wall, portrays, as Régis says, “this youth who are thirsty for liberation, for emancipation, for proof of human dignity, who have been rendered invisible — they have things to say.” He believes, despite it all, “there’s always hope — hope is in the collective, and collective intelligence.”

Credits

Photography Régis Samba-Kounzi