Though they should be top of our agenda all year round, Earth Day is a natural focus for conversations around sustainability in fashion. Those conversations, naturally, raise a number of important questions, but the one that leaves us scratching our heads is: what does sustainability in fashion actually mean?

When you dwell on the term, ‘sustainable fashion’ reveals itself as an oxymoron: how can an industry whose survival has long relied on the exploitation of natural resources to produce huge amounts of new goods ever truly be sustainable? Indeed, the inherent vagueness of the term — compounded by the lack of any clear guidelines regarding what can and can’t be called ‘sustainable’ — has left it open to exploitation. Greenwashing has become a ubiquitous marketing tactic; brands proudly tout clothes produced using ‘sustainable’ fabrics, for example, while obscuring supply chains and labour practices that are anything but.

As you’ll read below, it’s for reasons like these that some designers whose ways of working do embody the values you’d expect of a sustainable brand have distanced themselves from the term. Instead, they’ve chosen to lead with actions, rather than with words that have all but lost their meaning. The question to ask then is: what does that look like in practice?

To get a better idea, we asked 15 of our favourite ecologically and socially responsible designers to tell us what sustainability means and looks like to them, and how it informs what they do. Their responses speak to many crucial points — the often-overlooked social factors at stake; the challenges of working in a system skewed to suit the needs of large corporations; the explicit ties between conversations around sustainability and colonialism. In short, they give you an idea of how expansive and complex a subject sustainability really is.

At the same time, they demonstrate that while the issues at hand are plural and multifaceted, so are the solutions. Read on to hear designers from London to Lagos, Manila to Montreal share their thoughts on what they could be.

Richard Malone, founder of Richard Malone, London

In fashion, the use of the term ‘sustainability’ is often extremely vague. How would you define it? It’s very difficult to define now. People have embraced the term without looking at the meaning. We quite literally see brands calling something, which in no uncertain terms endorses modern slavery, as ‘sustainable’. Also, most truly sustainable practices were developed in female-led spaces, and have been erased through a combination of capitalism and patriarchy. This has led to highly skilled workers being called low-skilled because of their pay grade, and CEOs referred to as highly skilled because of their inherited privilege or take-home pay. Capitalism under the guise of sustainability is not sustainability: it’s a continued extraction of natural resources, creating more problems alongside the existing ones. At its core, though, sustainability has the potential to regenerate, educate and sustain. What makes it an especially important conversation in the communities you work with? As a young child in rural Ireland, I watched the entire linen industry collapse and move abroad. My grandmother made hospital gowns for years in hospital sewing rooms, which were also exported overseas, so that job became redundant. All of my family are makers, they worked in factories or on building sites — woodwork and metalwork, or painting and decorating. The lack of respect for this work is outrageous, and it’s left the most underprivileged people without anything, time and time again, as we constantly look for things to be done cheaper. For your brand, what does sustainability look like in practice? Several things. Every product that leaves the studio has been numbered and editioned since day one, and once they’re gone, they’re gone. We work with lots of different artisans and I consider each collection a project — it can be an introduction of a new fabrication or silhouette, but it’s never rushed. The collections are named after the date of completion and are not seasonal. More than 70% of the business is made-to-order, a figure that’s growing. I work with certified Woolmark wool for our signature pieces, ensuring fair trade, fair wages and fair treatment of animals. This includes deadstock fabrics, which aren’t a solution, but a reminder again of a loss of craft and excess. We’ve worked with Econyl to create fabrics from regenerated fishing nets that are constantly dropped in our oceans, to create a regenerated polyester. The leather pieces we recently launched were created from excess leather that would otherwise have been incinerated. We’ve worked with Oshadi Collective in Tamil Nadu, India to create beautiful handwoven jacquards from organic dyed cotton, which now supports a regenerative farm. I work with local Irish linen makers to create bespoke linen bases for all our ruched mesh pieces. We use plant-based dyed yarns to create our certified knitwear, which is all handknitted in London, and all of our tailoring is made in Finsbury Park. All of our products are made within the M25. What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? Speak to each other, listen. Remember that information is NOT knowledge. Knowledge is the digestion of information and the formulation of questions in relation to it. Question your own structure and beliefs, and share findings with others. Don’t do it to look good, do it because you actually care.

Priya Ahluwalia, founder of Ahluwalia, London

What makes this an especially important conversation where you are? My family is Indian and Nigerian and I live in London. I have seen first hand how lifestyles lived in London affect communities in India and Nigeria. Sustainability is invariably linked with conversations around colonialism — the way the West disposes of rubbish, pollutes ecosystems and exploits people in the African and Asian continents is so extreme. For me, it’s important to highlight this and figure out ways to change the balance, even if I can only do it a little. What are the most overlooked aspects in conversations around sustainability in fashion? Very often, the focus is only on fabrication and what materials are made of. But there is an ecosystem that needs to be considered. If everyone decides that a certain fabric is now ‘unsustainable’, what happens to the people that are producing the raw materials to make it? Again, these people are often ‘far away’ and therefore ‘out of sight and out of mind’, but there is a human element to sustainability that gets forgotten. What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? We need to be careful of putting the onus on small and independent businesses to create real change. I really think the focus needs to be on huge corporations to invest in sustainable practices and have huge impacts, both on the environment and also on economies of scale. If they spend more on sustainable options, prices become better and more accessible to everyone else.

Ditte Reffstrup, co-founder of GANNI, Copenhagen

In fashion, the use of the term ‘sustainability’ is often extremely vague. How would you define it? We don’t call ourselves a sustainable brand as we recognise the contradiction between fashion, newness and sustainability. It’s important to underline that this approach isn’t an excuse to not act responsibly. We’re committed to making better choices every day across the business to minimise our social and environmental impact. We see this as our moral obligation. What aspects do you think are most often overlooked in conversations around sustainability in fashion? I think sustainability is often overlooked at the beginning of a product’s life in the design stage. We work a lot with repurposing past-season fabrics, but our main goal is to create collections that are 100% traceable and made from certified fabrics. You’ve got to share your highs and lows, something we do on a daily basis on our @ganni.lab account. For your brand, what does sustainability look like in practice? In 2020, we launched our Responsibility Gameplan where we set ourselves 44 tangible goals to reach by 2023 across four main pillars: People, Planet, Product & Prosperity. Having this in place helps keep us on track on huge topics like 100% traceability in our supply chain. For us, sustainability also means putting our money where our mouth is. It’s going to cost you as a brand if you want to be more responsible. It means engaging in tangible and quantifiable projects like carbon mapping and offsetting, hiring resources to create change and investing in innovative solutions and fabrics. And all of this needs to be transparent to your community, it can’t just be value-led statements. This is also one of the reasons why we publish an annual sustainability report that came out this week. It’s about holding ourselves accountable.

Kenneth Ize, founder of Kenneth Ize, Vienna/Lagos

In fashion, the use of the term ‘sustainability’ is often extremely vague. How would you define it? It’s about creating in a way that doesn’t make anybody feel less human. It’s about empowerment. It’s about respect. What makes it an especially important conversation in the communities you work with? There are different communities where I’m from in Nigeria, and some are really built around handwork and craftsmanship — work that brings value to the world. There are compounds where you can find someone that could make a fabric without electricity or a water supply — just using their hands. That’s the height of craftsmanship. It’s so important to preach that around the world, to ensure that the value of the culture and the knowledge that these places generate is appreciated. What are the most overlooked aspects in conversations around sustainability in fashion? Transparency! There are designers that come to Africa, produce things, and purport to be supporting Africans by selling these goods. But how are they actually impacting the lives of the people they work with? Where is the money going? Because I can tell you that the people producing these products are still in the same place — nothing has changed in their lives. This lack of transparency amounts to an act of white supremacy, and people don’t question it. For your brand, what does sustainability look like in practice? I can take you to where my fabric is from; I can tell you how much of a certain fabric a weaver has made; I can tell you how much he’s making at the end of the month. It’s really just about understanding that there is value in what they do, and showing them that; and building relationships that ensure that the lives of the people you’re working with are comfortable. Doing business in a way that doesn’t make anybody feel less human.

Sean Barron, CEO and co-founder of RE/DONE, LA

In fashion, the use of the term ‘sustainability’ is often extremely vague. How would you define it? Sustainability encompasses our ever-evolving commitment to create without harm. We offer heritage styles that are relevant today while respecting our employees, diverse community, and planet. Responsibly made, circular clothing and social sustainability are our two major focuses. What makes it an especially important conversation where you are? Our sustainability efforts go beyond our products, but also into the people and places that contribute to them. We only partner with factories that take significant action to minimise their impact. Our Mexico-based denim factory is one of 200 factories that is Cradle-To-Cradle certified — a globally recognised measure of safer, more sustainable products made for the circular economy. It is also a part of the Alliance for Responsible Denim. Another initiative we are launching this month is RE/SELL, a peer-to-peer resale platform on our website that allows no-longer-worn RE/DONE pieces to be rehomed. RE/SELL will give 80% of the sale back to the customer for store credit. For launch we are partnering with the incredible Sheltersuit, donating 5% of sales to their non-profit organisation providing shelter and outerwear for the homeless made from upcycled materials. What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? For brands progressing towards sustainability and circularity there are a number of resources that offer practical and actionable support and guidance, namely the following: 1) The Ellen MacArthur Foundation: a UK based charity that is an incredible resource promoting circular economy. 2) United Nations Sustainability Development Goals: the UN has put together a comprehensive resource of sustainable development goals (SDGs) that are the world’s shared plan to end extreme poverty, reduce inequality and protect the planet by 2030.

Saeed Al-Rubeyi, co-founder of STORY mfg, Brighton

What makes it an especially important conversation in the communities you work with? Unchecked capitalism and colonialism are giant driving forces for planetary terror. I know that last sentence causes people to roll their eyes but it’s clear the pursuit of endless growth and profit above all is destructive, and the people who pay the price first are not those living in the West. People live and work in toxic environments, forced to work for not enough, and poison their own land to feed the machine of cheap, fast-trend-led shit. What are the most overlooked aspects in conversations around sustainability in fashion? Pragmatism and nuance. I hate to harp on about ’the West’ while sitting in my chair in the UK but almost every conversation we see is led by ‘industry’ leaders in the West talking about giant global solutions cooked up in the US and Europe. We don’t hear about small scale, local, natural, dynamic ones. In India and Thailand, people we work with create regenerative practices, bring back dead land and re-wild areas using ancient knowledge — they have local solutions to the issues created by climate change that work for them but wouldn’t work anywhere else and that’s cool. In the UK, the most powerful thing we can do as consumers is to give up animal products and stop flying — things that are meaningless to the ladies that weave with us in rural Thailand. What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? There needs to be more legislation for sustainability and there need to be financial incentives for companies to create more eco-conscious products and fight climate change. Most people don’t know it, but the government here in the UK gives companies money off taxes for doing certain activities — one being Research and Development (the idea being they want to promote UK companies being leaders in emerging technology). This creates an ecosystem where companies go out of their way to try new things because they can write it off the tax they would have paid anyway and they might hit on something great. The same, at a minimum, needs to be available to companies that are making meaningful change. We need people with real knowledge in places of power lobbying governments to codify what is a ’sustainable practice’ in the same way we make an effort to decide what is and is not a ‘human right’, and we need litigation for offenders as well as incentives for change-makers.

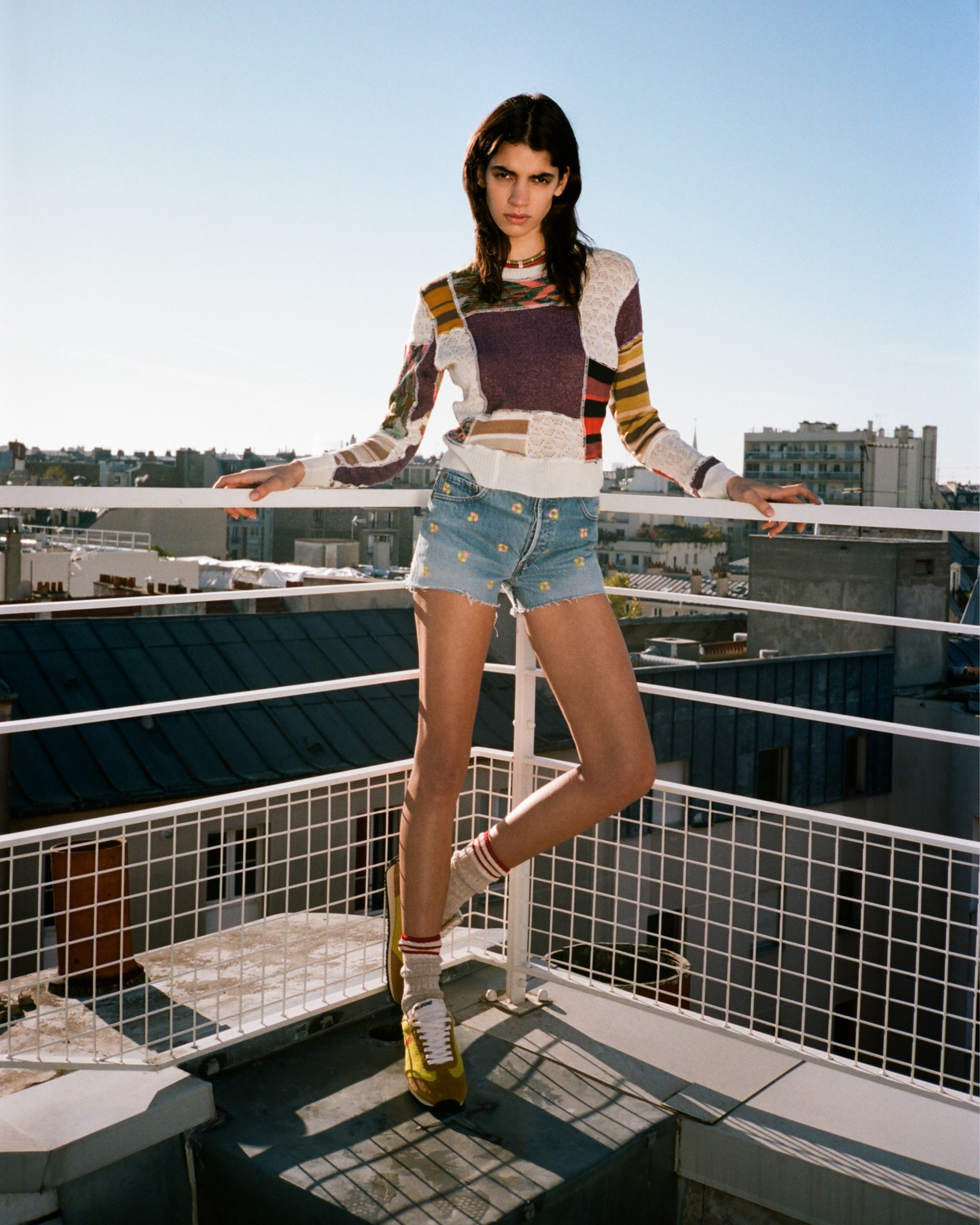

Guillaume Henry, creative director of Patou, Paris

What makes sustainability an especially important conversation where you are? Nobody was necessarily expecting Patou to come back, and if we wanted to make a comeback, it wasn’t just a question of taste or style. I didn’t want it to be another brand that’s rooted in this idea of being French and inspired by Parisian couture — I wanted to make it relevant for today, to connect with society and the world we are living in. For your brand, what does sustainability look like in practice? Our focus from the start has been on doing less but better; creating tight, edited collections. We don’t kill what we’ve done in previous seasons. There are new things each season, but there are also the essentials — the perfect shirt, the perfect jeans that use no water in their production, the perfect pea coat, the perfect trench coat. After two years of Patou, more than 75% of the garments are created in recycled or organic fibres. You’re also invited to ‘visit’ our factories by scanning a QR code on a recycled fabric tag in each garment, where you can also see interviews with the people that create the clothes. Fashion is, first and foremost, about creativity, and therefore about the people that are creating — otherwise, we’re not talking about fashion, we’re just talking about clothes. What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? Fashion is a dialogue, it’s not only about you talking to the world. It’s about observing which directions the world is moving in and people’s needs. People don’t want sustainability to be a sexy accessory — it has to be real. It should just be part of the fabric of how we do things.

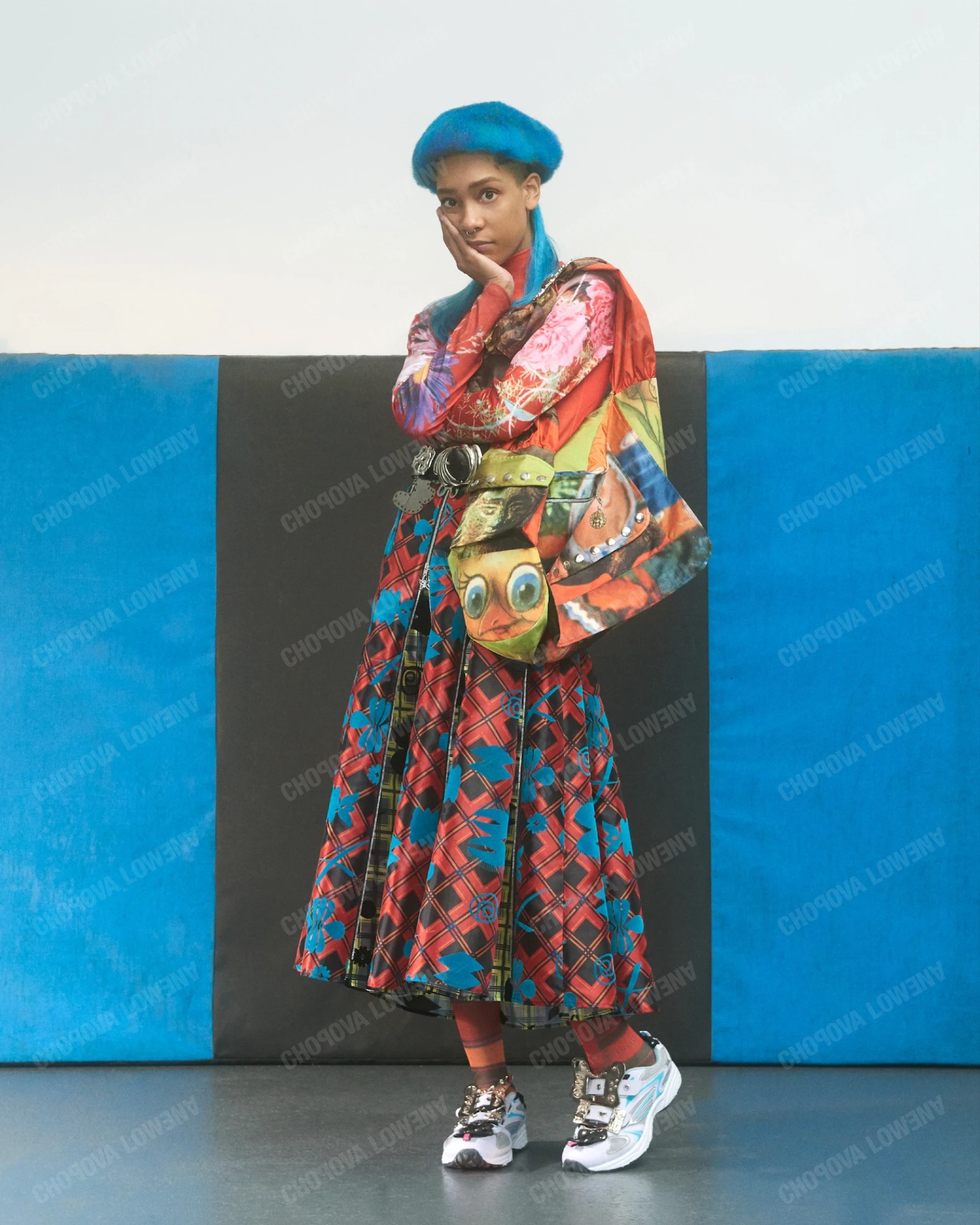

Emma Chopova & Laura Lowena, co-founders of Chopova Lowena, London

What makes sustainability an especially important conversation in the communities you work with? We upcycle a lot of folkloric and vintage textiles, some from England but most from Bulgaria. They’re so special and carry so much history but are usually thrown away. What are the most overlooked aspects in conversations around sustainability in fashion? The people involved in the production of clothes are talked about very little. We have always wanted to create a reliable network of craftsmen and makers, which we treat as family. We’ve found an amazing community in Bulgaria, a production network of women across the country led by our atelier head who outsources to women in their homes and to the small ateliers we use for pleating, casting and leatherwork. What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? Being sustainable is not always convenient. It requires investment of time and money and creates a lot of obstacles in the production process. But contributing less to the incredible amount of waste our industry produces makes it so worth it. Large brands need to commit to making use of their waste, and working more with deadstock and responsibly sourced textiles, as they are ultimately the greatest contributors to the issue. The change needs to come from everywhere, though — from brands and retailers, but also from customers, by buying responsibly and not giving power to fast fashion.

Marie-Ève Lecavalier, founder of Lecavalier, Montreal

In fashion, the use of the term ‘sustainability’ is often extremely vague. How would you define it? I define sustainability as a way of reinventing the creation and production processes. In my view, for something to really be sustainable it has to be well thought out — both in terms of reducing the environmental impact of its production, and in terms of challenging the traditional operational mechanisms of the fashion industry. It’s about empowering smaller, forward-thinking ecosystems that are willing to create alternatives to the mainstream. What are the most overlooked aspects in conversations around sustainability in fashion? Conversations about sustainability in fashion are closely related to the textile and the composition of garments, but the production system and the minimum metres of fabric you’re required to purchase, for example, aren’t discussed. The fashion industry still revolves around the production of large quantities of styles and fabrics — even if your polyester nylon is 100% recycled, to be able to use it, you need to buy an insane amount, a great part of which will be thrown away in the end. For your brand, what does sustainability look like in practice? Sourcing what is available, and applying our creativity to it. For instance, we create woven leather pieces with leftovers in our studio, and for the more industrial pieces, we work closely with factories to find ways to use deadstock materials available at our suppliers. For our leather-embroidered Merino wool dress, our knitters were able to develop a new embroidery technique by sourcing deadstock trimmings from a local leather factory, and all of our more intricate leather and textile pieces are produced in our studio in Montreal, using materials sourced from local deadstock suppliers.

Hillary Taymour, founder of Collina Strada, NYC

What makes sustainability an especially important conversation where you are? New York is one of the few places in the world where all of our garbage sits on the street. We are reminded daily of how much waste is produced. Seeing this has forced me to rethink how we use materials — we try to hang on to every scrap we can when making a garment by re-engineering patterns to be more fabric conscious, for example. As a growing fashion brand, I never want to be part of the problem, only helping with the solutions. For your brand, what does sustainability look like in practice? It means: paying fair wages for production; having our production steps away from our studio to remove shipping back and forth; sourcing deadstock fabrics before we think about creating new fabrics. For in-person shows, we try to use natural set elements and donate them to local gardens afterwards. We even planted the grass for the Elizabeth Street Garden last year and I’m happy to announce that it’s thriving! What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? There should be laws in place and people who audit claims around sustainability. In general, large corporations need to be regulated. The number of goods I produce versus the Nikes, Zaras and H&Ms of the world cannot be compared. They need to be held accountable before any real change can happen.

Shiva Vaqar, co-founder of Vaqar, Tehran

What makes sustainability an especially important conversation where you are? Conversations around sustainability have brought a vast amount of interest to local artisans around Iran, which supported the growth of their practices and the awareness of their craftsmanship. The biggest challenge we face when it comes to sustainability, though, are the restrictions on the import of up-to-date science, technology and materials due to the political issues we have here. It makes it quite hard for designers to make more conscious choices when sourcing materials both inside and outside of Iran. What are the most overlooked aspects in conversations around sustainability in fashion? When talking about sustainability in Iranian fashion, we usually emphasise the social aspects. I’ve noticed, though, that there are more conversations around conscious sourcing and operational technologies in the West. Also, while awareness of sustainability is increasing everywhere, these kinds of conversations mostly take place in fashion communities. What’s then overlooked is how to make these conversations engage a wider audience, reaching people who are not interested in fashion’s inner workings, but still consume it. What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? One of the greatest problems in the fashion industry is its fast pace. It doesn’t leave designers enough time to think and make proper decisions. If we slow down on our own, we risk being overlooked by audiences and buyers due to the cruelly competitive nature of the system. Finding a way to work at our own pace, while finding new ways to connect with our audience and be more transparent about our values, has given us a way to exit this defective cycle and start to recreate a new system.

Luke Stevens and Arnar Már Jónsson, co-founders of Arnar Mār Jōnsson, London/Reykjavík

What are the most overlooked aspects in conversations around sustainability in fashion? The ways in which a wearer’s relationship with a piece evolves over time. We’re interested in the idea of extending a product’s lifespan. This relates to ideas of durability, performance, functionality and use; but these same ideas can also shorten a garment’s lifespan by defining a garment’s use too specifically. We try to approach things as openly as possible, through ideas of reversibility and adaptability, for example, embedding different uses into a single piece. For your brand, what does sustainability look like in practice? It extends beyond sourcing, supply chain and the design of the collection into all our working relationships — both the ways in which we collaborate with suppliers but also our relationship with nature. Our team is based between many different locations, and with recent restrictions on travel and delayed shipments due to Brexit, we’ve had to look for ways to work more efficiently between countries, digitising a lot of our design process to limit travel and excessive shipments. We also try to work as locally as possible — using local plants which we harvest ourselves within our dyeing processes, and working closely with skilled manufacturers that specialise in certain techniques to develop our collections. What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? To really refine an idea can take several seasons, so you have to take a long-term view. We’re interested in working closely with industry partners to establish new ways of collaborating, rather than directly opposing current practices. True innovation comes out of dialogue and exchange, rather than operating in isolation.

Carl Jan Cruz, founder of Carl Jan Cruz, Manila

In fashion, the use of the term ‘sustainability’ is often extremely vague. How would you define it? It’s about the big picture of what we want to be able to preserve, grow and pass on. Whether it is a craft, a methodology, or the welfare of certain parts of the fashion industry. What makes it an especially important conversation where you are? I think the idea of sustainability is still limited here. It is a concept that requires a lot of resources to access. In the Philippines, there are a lot of conversations and radical changes that need to be accommodated so that we can catch up on how we can work more sustainably. What are the most overlooked aspects in conversations around sustainability in fashion? The actual roots of creation and labour. Sustainability is a term that’s often used when it comes to marketing and sales, but it often isn’t discussed when it comes to creation. And these conversations can’t just be limited to using organic cottons, natural dyes, and upcycled fabrics — not everyone can afford to work with these things to begin with — they need to focus on how we can build a healthier work system that nurtures creative passion and people’s livelihoods at the same time.

Amy Trinh and Evan Phillips, co-founders of WED, London

What makes it an especially important conversation where you are? Because we started out exploring bridal and occasion wear, this is a conversation that will always be important to us. We know that there will always be a market for ‘one-day dresses’ and often they are incredibly crafted creations; keeping this level of craft alive is also important. It’s about offering an alternative. From a sustainability standpoint, to spend so much on something you can wear so little made absolutely no sense, and everyone we knew was thinking the same. It was so important for us to create something that’s that special, but that can be worn day-to-day. What aspects do you think are most often overlooked in conversations around sustainability in fashion? People often think sustainable solutions are difficult to implement, or that it’s just about fabrics. It’s about thinking about every aspect of the creation and output, and how we can make small tweaks in order for it to have less impact. One thing we try to get people to think about is how they value the pieces that they buy. This is why we refer to the attachment you invest in buying a wedding dress, for example, as the standard for how we should regard all our purchases. It’s such a perfect example of an investment piece that is cherished, but we want to evolve beyond that — you should be able to wear it all the time. This is why we say WED sits somewhere between a gown and jeans and a t-shirt. What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? Often, it’s about looking at every step of the process and seeing what small changes you can make that don’t sacrifice the design. It’s about looking inwards, embracing the challenges that come with it and knowing that not all things work for every brand. We really try to design in a way that feels timeless with the aim of slowing increased buying habits, asking people to think before they buy, and keep and cherish the things they do buy.

Phoebe English, founder of Phoebe English, London

What makes sustainability an especially important conversation where you are? We are based in London, and we live in a country that has an addiction to fast fashion. We consume more clothing than any other country in Europe. Because of that we have even more duty and responsibility to be working towards beneficial ways of designing and producing garments. We define it as ‘less damaging fashion practice’. For your brand, what does sustainability look like in practice? Our sourcing first starts with locating points in the textile industry where there is waste produced (rather than choosing what we like). Then the design focuses on the particular type of textile waste we have acquired — whether we are trying to use up little parts, or huge quantities. We also think about the studio’s activities as a way to clean up after the fashion industry as we go. We are exploring things like the biodegradability of our clothing — like making studio soil with our textiles, so we can positively input into the soil systems around the studio. We are also making links with positive agricultural practices, and looking at how we can support them with our studio actions. Less damaging fashion practice now forms the bedrock of every decision we make in the studio. What steps do you think need to be taken towards creating a more sustainable fashion industry? It would be a positive move if our relationship to clothes could improve, and if businesses could help people to be able to also find joy and pleasure in how things are made and where they have come from rather than solely how they look, feel and fit.

These interviews have been edited and condensed. Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more fashion features.