After receiving her BA from Harvard University in the late 1970s, Sage Sohier embarked on Americans Seen, her first major project at the outset of her photography career. Fascinated by environmental portraiture and what it revealed about both people and place, Sage began travelling the nation, many images made over the summer when she was able to road trip across the USA. Intrigued by how a person’s environment gives clues to their character and personality, she sought to create complex and layered images as intricate as the people she met along the way.

Sage’s mother, Wendy Morgan, laid the foundation for her lifelong love of observing people in their natural environment and the ways in which photographs could tell stories about who we are and how we move through life. Wendy had been a fashion model in the late 1940s, posing for no less than Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, and Horst P. Horst, and had a natural flair for glamour and showmanship. Sage remembers lying on the bed, watching as her mother dressed up and got ready to go out for the evening. “I remember lying on the bed with the dogs and watching her. She was very theatrical. She would point out all her flaws, and I was mesmerised by the whole thing,” Sage says.

“When I started photographing as a young adult, I thought that what I was doing was entirely different from fashion photography. It was really only later, when I started photographing my mother for Witness to Beauty that I realised how much observing her and looking at those fashion pictures of her when I was a child was responsible for my interest in photography. Even if you’re doing work that’s on the street that has a relationship to documentary photography, you are imposing on your own vision on the people you photograph. But I don’t think I understood that at the time.”

During her college years, Sage began to explore the narrative possibilities of photography and the concept of it as an art form in its own right. “Tod Papageorge was a visiting artist during my senior year, and it was an unbelievably lucky break,” Sage says. “He was incredibly eloquent about the medium. He somehow made me feel not only that I wanted to become a photographer, but also that it was possible for me.”

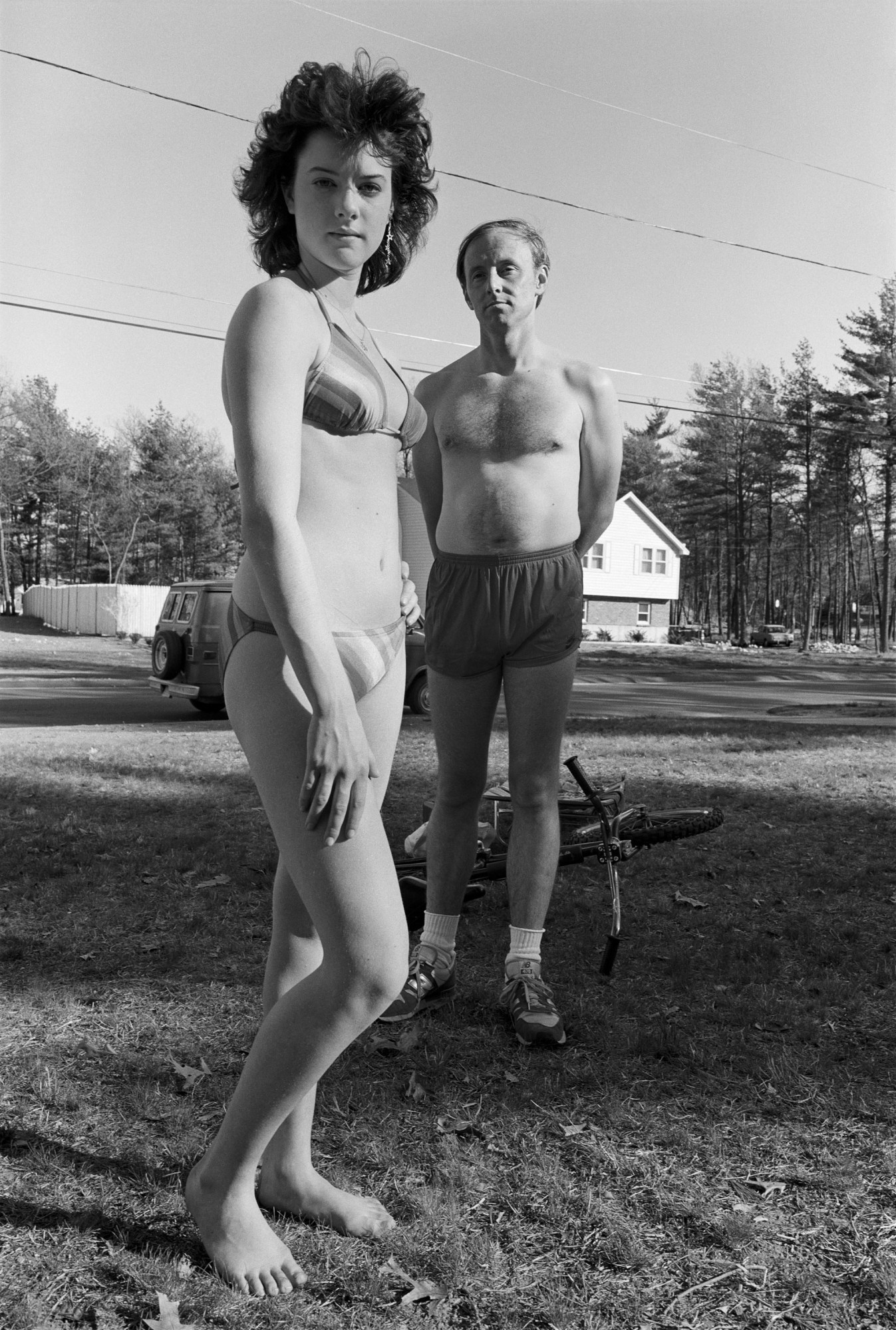

After looking at the work of Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and Interior America by Chauncey Hare, Sage felt a burning ambition to make original photographs. In 1979, she embarked on Americans Seen, which later became a book. “I had a vision of the world that I wanted to show in pictures, but I couldn’t have put it into words, but when I went out with my camera, I knew what I was looking for,” she says. “At that time, photographic road trips, trips were a rite of passage for photographers, like Robert Frank when he did The Americans. It seemed like the thing you’re supposed to do, but I discovered early on that it didn’t work for me to go off for a year on my own.”

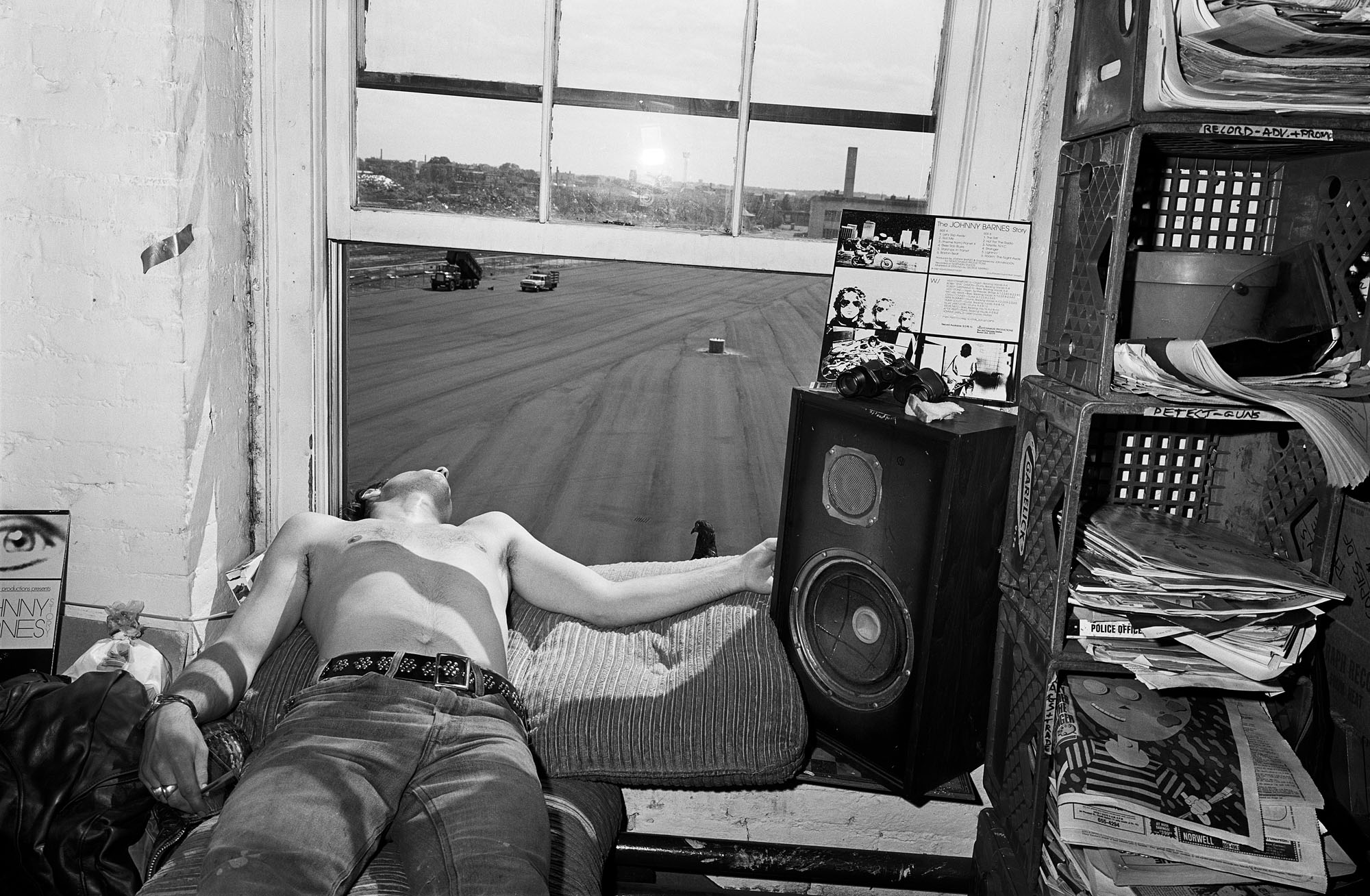

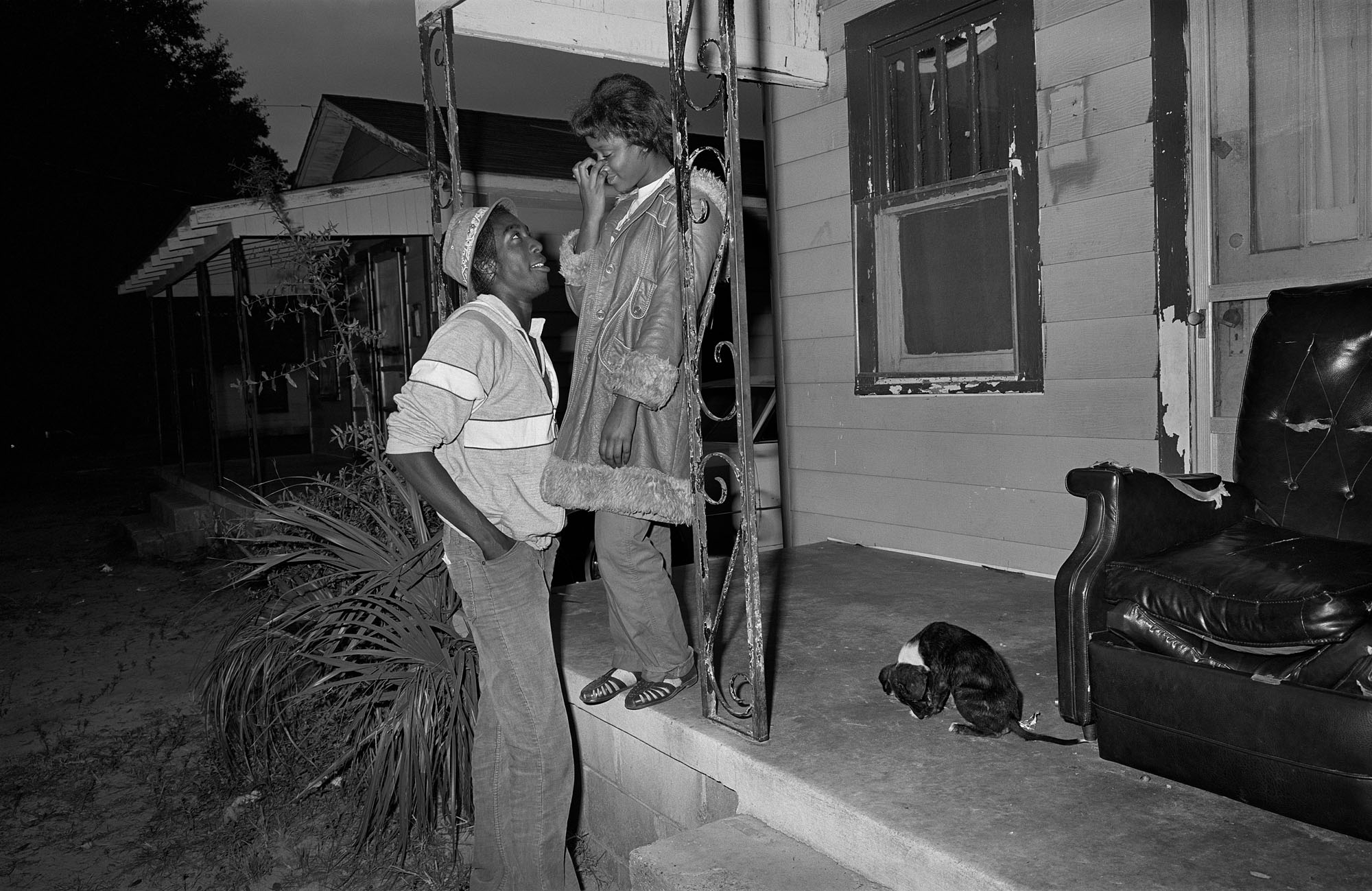

Instead, Sage regularly took 1-2 week trips on the road where she could escape the distractions of daily life and fully immerse herself in the practice of environmental portraiture. During the winter, she headed south, where it was easier to find people hanging outside, with greater spontaneity than setting up indoor photo sessions. “Photography gives you license to talk to people and is a wonderful entrée into other people’s lives. I learned a lot more about people and the world than I would have in my studio,” she says.

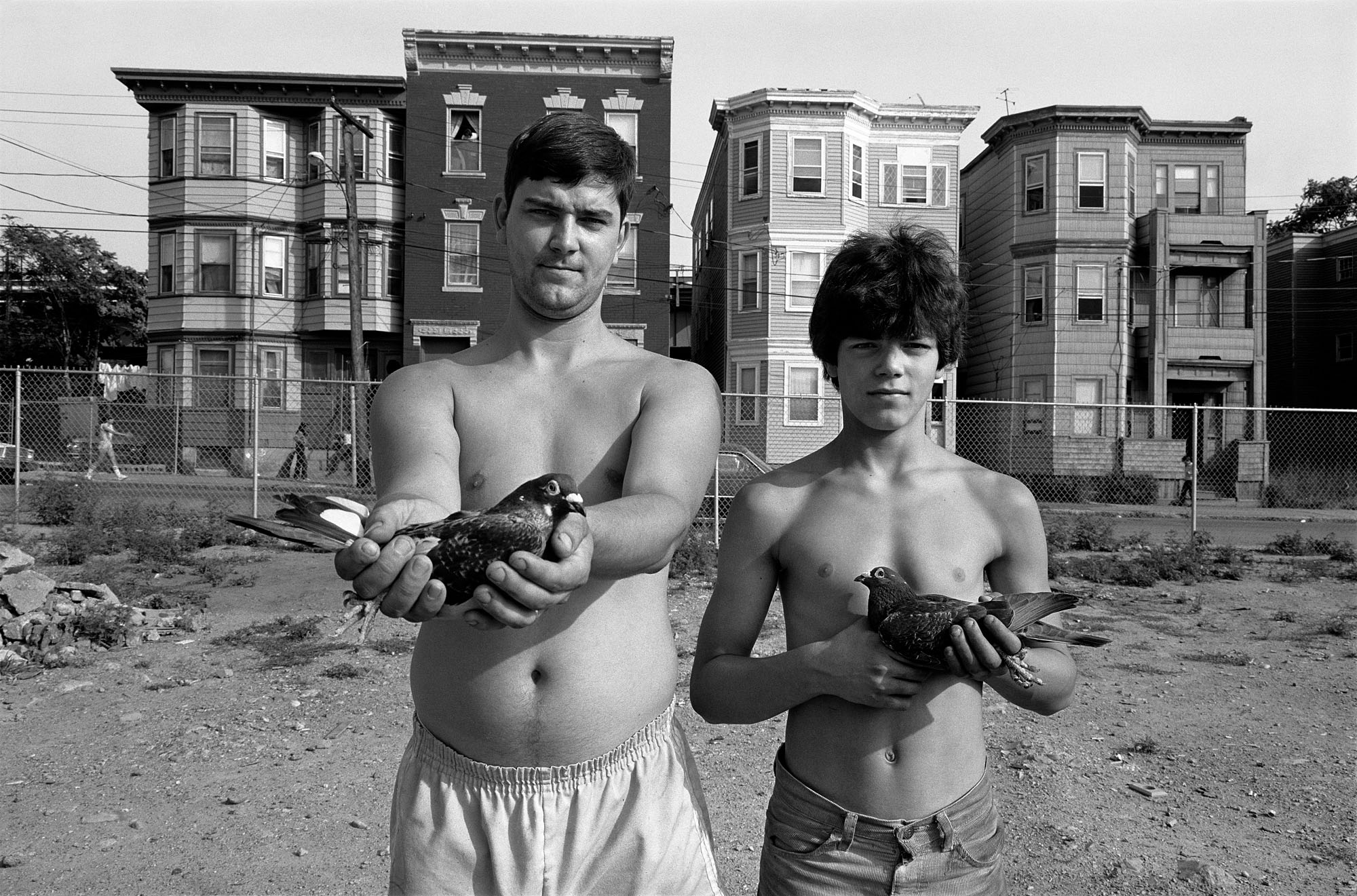

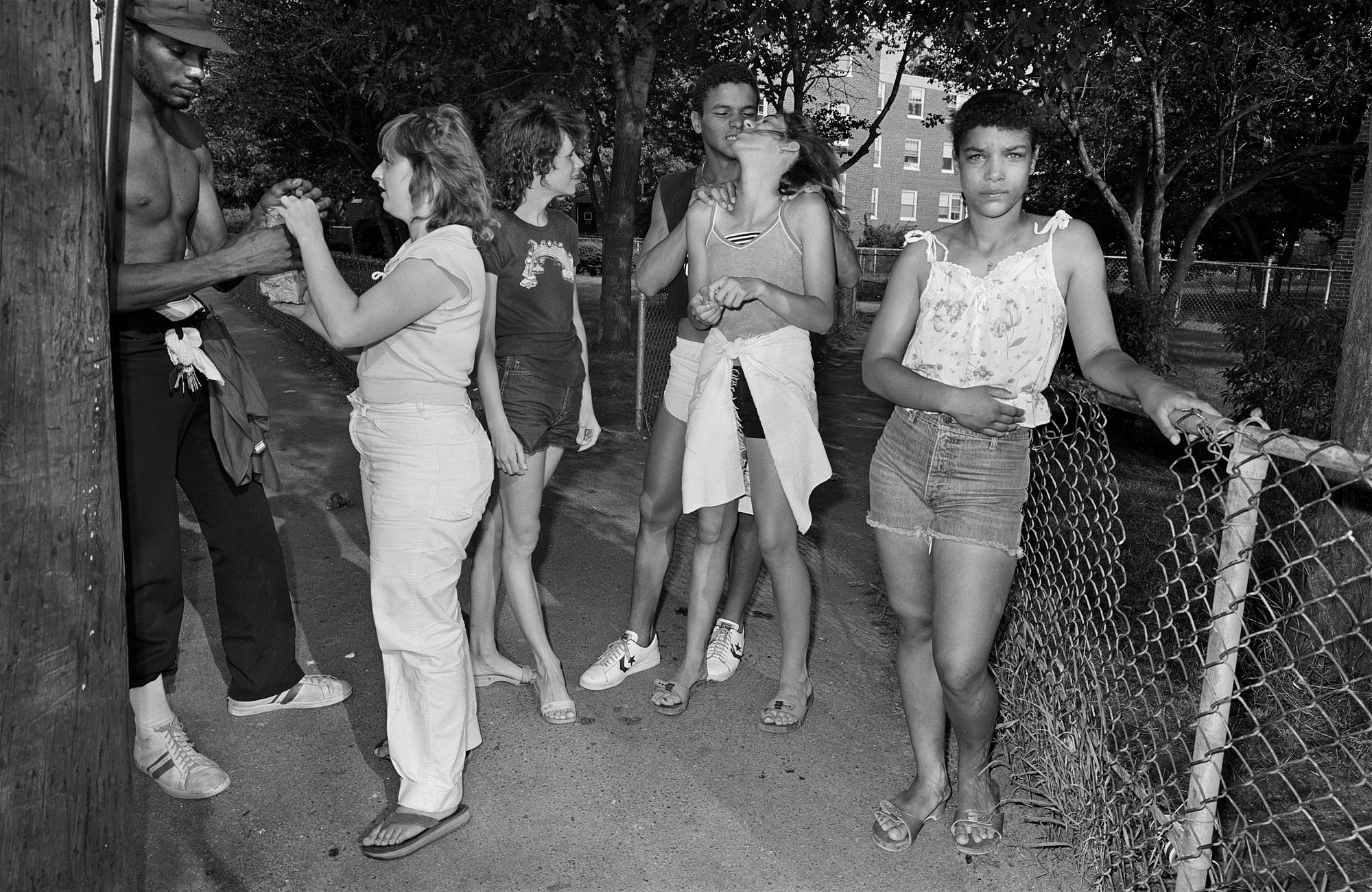

“I was looking for interesting people in an interesting environment, or for some kind of interesting event, like the teenagers who are lifting weights. But when you run up to people and ask permission, which I always did, everything changes. People stop doing what they’re doing and become a little more self-conscious. I found that by spending a little time with people, I could get back to the essence of what I’d seen that has interested me. You feel included in their lives and experiences in a wonderful way.”

No matter where Sage travelled, children and teens welcomed her interest in their lives. “It’s best making a picture with people when it’s a form of collaborative play,” she says. “A certain kind of enthusiasm can be infectious, and people understand that there’s something you find compelling about them, and they respond to that.”

Sage also brought that same spontaneity and adventure to her travels across the United States, exploring the regional differences of the country in the final years of the analogue era before digital technology transformed every aspect of our lives. “I was driving around the country without a cell phone or GPS, getting lost, discovering things, and getting to know different kinds of people,” Sage finishes. “The pictures matter, but the experience is what makes it rich.”

‘Sage Sohier: Americans Seen‘ is published by Nazraeli Press. Joseph Bellows Gallery represents the vintage work.

Credits

All images Sage Sohier © Americans Seen