Many of us, at this point, are heading into our third week of self-isolation, whether by choice or as enforced by the government. It’s brought out something different in everyone: some are productive, others have shaved their heads, many are baking bread, and most spent the first few days moaning like grounded teenagers. Overnight, we’ve had to shift how we connect, work and enjoy our downtime. And while many people have checked the privilege that comes with moaning about being self-isolated and not out on the frontlines of a pandemic, and embraced sourdough starters, knitting and embroidery, there is one activity that unites us all. Being online.

Now all we have is the internet, and so the face and content of the online world is changing rapidly. It’s perhaps not surprising that we might have forgotten the endless possibilities of the world wide web; for a while, it’s been mostly a source of chaos, competition and cruelty that made it more stressful to be online than off. It’s a shame that a tool initially intended to connect us has divided us and fostered trolling, bullying and a deluge of fake news. By comparison, in the 2000s, being bored and having an internet connection led me to some of my favourite hobbies, music and friends. While internet world 2.0 had all but lost that sense of comfort, it’s re-emerging as a lifeline throughout our strange pandemic time.

After all, the internet’s role, as we had briefly forgotten, goes far beyond entertainment. As the BBC recently pointed out, had coronavirus happened in 2005, we would be in a far worse situation. Without the ability to easily order food, learn new skills, find medical information or connect with loved ones, it would have been near impossible to isolate properly or maintain any kind of sanity and security for those stuck inside. As the virus has spread news has also become more democratised, and many websites have dropped their paywalls to make their resources on COVID-19 free, empowering everyone with information. People are using the internet to creatively raise money and resources for hospitals, food banks and other people in need, as well as helping their immediate neighbours through Mutual Aid groups.

Despite millennials and gen z’s status as the loneliest generations, we do, generally speaking, maintain friendships through a mix of face to face contact and social media. Without the possibility of meeting down the pub, Zoom, the video-conferencing app, has proven itself as an unlikely method of maintaining not just work but personal relationships during lockdown. We’re having “parties”, movie nights and even pub quizzes with groups of friends from the comfort of our own homes, finding inventive ways to connect that go beyond chatting. With fewer distractions and a shared feeling of mortal terror, we have no choice but to talk about what we’re really feeling and experiencing.

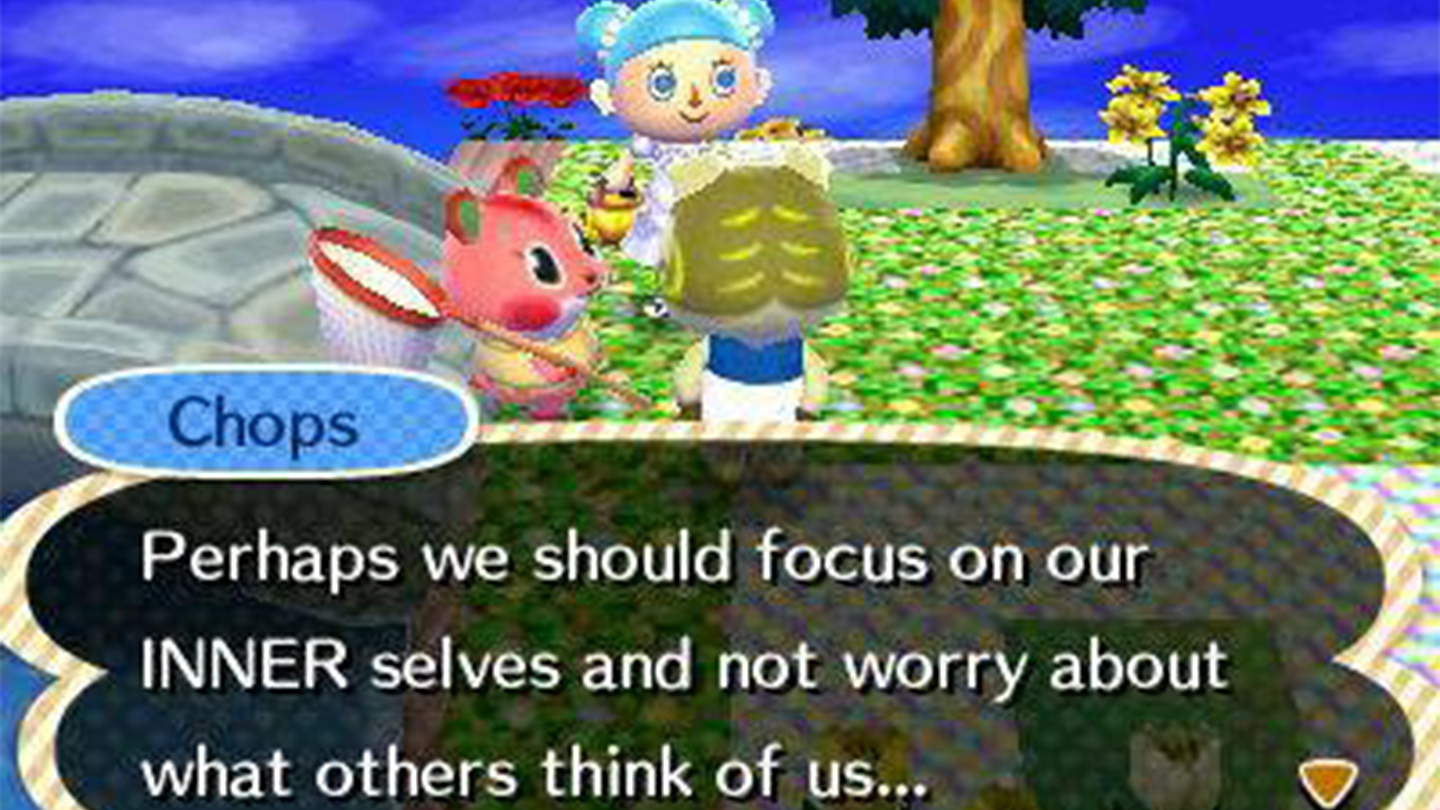

The fear that boredom instilled in many at the start of lockdown is understandable: after all, how long ago were you truly bored, with nothing but yourself to entertain you? For a population living with constant distraction, the prospect of 12 weeks or more left alone with our own thoughts was daunting to say the least. But we needn’t have worried. In fact, seeing people get past that boredom and share their dorky hobbies is one small pleasure in lockdown. Whether it’s making bread or doing a dumb dance you learned on TikTok or painting or playing Animal Crossing, when we’re left to our own devices, rather than falling into atrophy, we find what we really like. The restraints of staying home have forced TikTok creators to be more inventive, too, with one family creating a “club” in their home. These kind of low-budget, one camera videos in a restrictive setting are what made the earliest, dumbest videos on the internet so memorable, and a move away from slick, sponsored content is welcome right now.

Maybe our bar for entertainment has just been set too high, but with everyone stuck at home and our brain cells dying day by day, our hardened cynicism has been dismantled and abandoned. Many of us are keeping in touch via Myspace bulletin-style chain-tag games, like sharing a childhood photo on Instagram then tagging four mates in and conning them into doing the same thing. Some of us are filling out blog-esque quizzes over Instagram, rediscovering our Photobooth app, and making silly content just for fun. We’re rediscovering the idea of passing time just for the sake of it, letting go of the concept of monetising all of our hobbies, and it’s a thrill to see even the coolest people engaging in painfully earnest trivia games over Instagram stories.

It’s likely, too, that a self-indulgent, early-2000s LiveJournal-type internet is just around the corner. Already, people are whispering in some corners of the internet about the return of blogging, which could only be a good thing. Diaries are a necessary, useful tool in times of crisis. Exploring how we feel and sharing our singular experience with others is not only a historically important practice, but it’ll give us the opportunity to get to know people beyond their polished articles, flippant Instagram captions or throwaway Twitter posts. And that can only be a silver lining to come out of the crisis.

Everyone is becoming less polished, our online personas falling away as we either decide it’s not worth the effort or just want to show our true selves online amid a global pandemic. Even celebrities are in on it: while their social media profiles have long been closely managed, they’re taking to their own accounts to post livestream singalongs, funny videos, and clips of them cleaning their own toilets. Recently, the Backstreet Boys “reunited” to sing “I Want It That Way” in a video that quickly had people arguing over who the hottest one is (in 2020!). While Vanessa Hudgens and some other celebrities have used the internet to show just how out of touch they really are, many others have shown something approaching a true self.

Of course, it’s not all positive. As with all things, the pandemic has brought out the ugly side of some people online. Twitter is a tool for public shaming, and as new rules on behaviour emerge, there’s always someone itching to share a photo of a crowded tube for the disapproval of other narcs. But it’s also proved that the internet is only as evil as the ways we choose to use it, and lately, it’s been a site of genuine connection and fun, early-internet style distraction. Mutual fear has forced us to communicate differently, too; we want to talk, to connect, to think about something other than blind terror. All we have is the people we love, and it’s being separated from them or fearing for their lives that’s helped us to see that. We’ve had to relearn how to communicate and pass time, and hopefully we will carry that with us long after we’re allowed to be back down the pub with our friends staring at our own phones.