Steven Klein is reminiscing about Paris in the 1990s, when fashion photography was, in his opinion, truer to its values. “Editors back then thought in a more photographic way,” he says. “Now the editors are leading photographers to do what they think is right for the images.”

A graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, Steven was heavily influenced by the likes of Carine Roitfeld (former editor-in-chief of French Vogue) and stylist Nancy Rhode (“she brought clothes over to New York in a bin bag”) as he started his career shooting with Dior and Calvin Klein. Paris and Milan still dominated European taste, while the grungier aesthetic led by photographers like Corine Day led the way in London. “Being American at the time, it was almost as if you had everything against you,” Steven says.

Speaking from his home in New York on the last day of fashion week, Steven is upbeat, his critiques of the industry more constructive than lamenting. His training firstly in ceramics, then drawing, painting, glass-blowing and sculpture might explain his restlessness with the fashion world, but he has since carved out a space where his love of Bacon, Picasso and 20th-century cinema can inform his shoots.

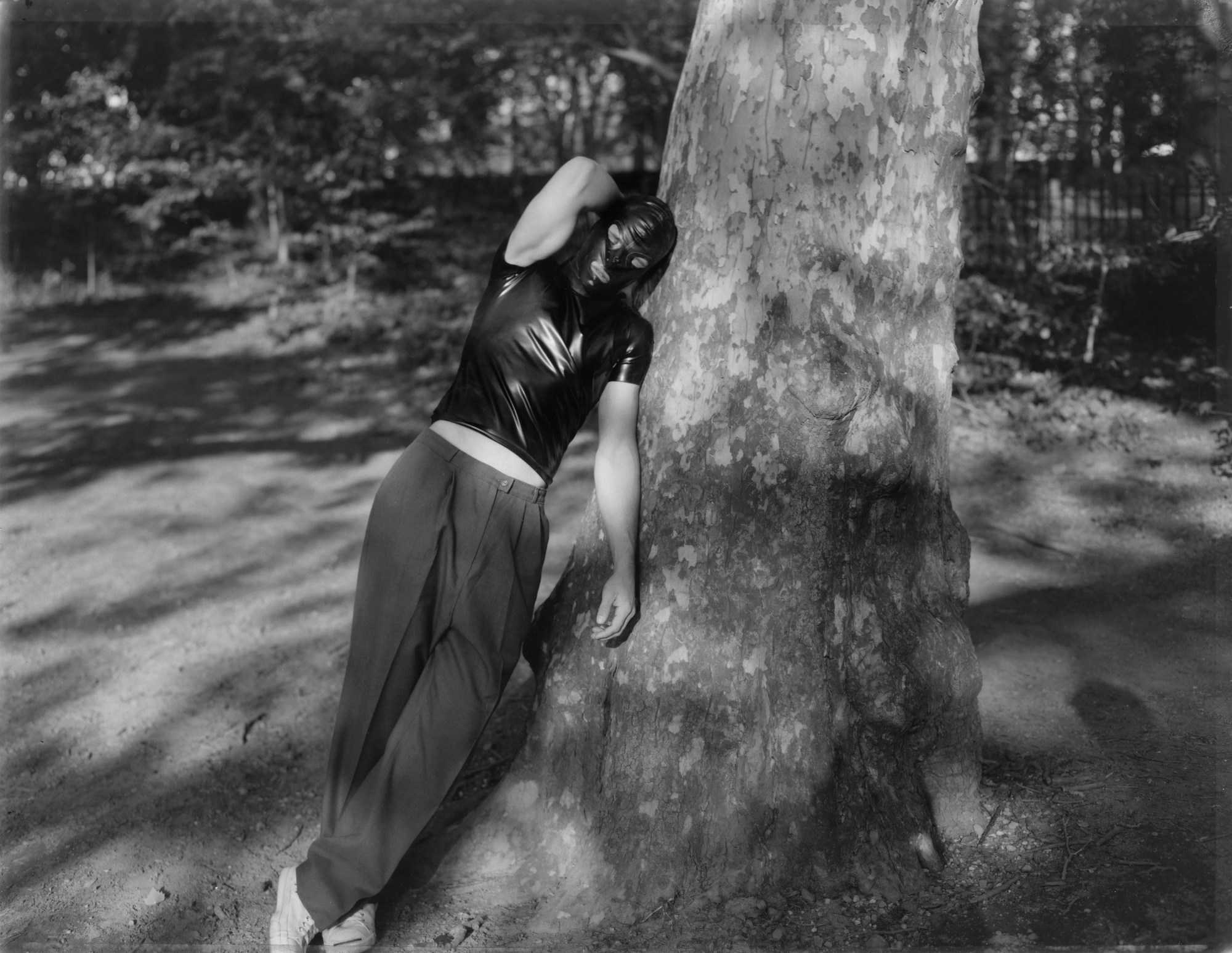

“Years of figure-drawing and studying anatomy helped me with how I pose models,” he says. His anatomical images of horses are a prime example, an exercise in calm, studious repetition. “I see photographs as paintings. I create the groundwork first before I insert the subject: the colour, the perspective, the composition.”

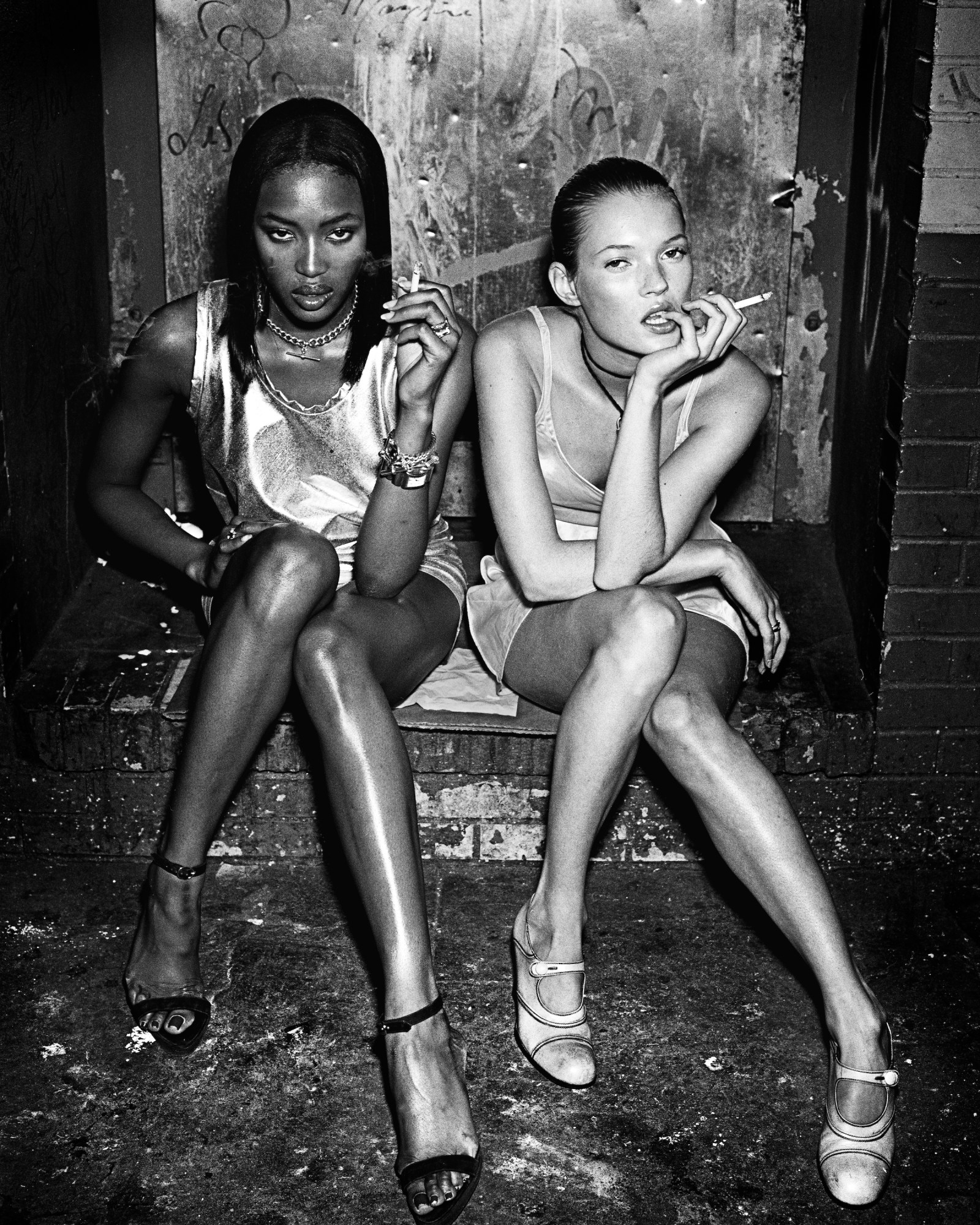

This director’s approach has guided Madonna, Kim Kardashian and Kanye West in shoots that often recast celebrities as subversive characters. All are included in Steven’s first monograph, a major photobook of his commercial and artistic work from the last 30 years. The 450-page volume begins with his ‘death kit’ assemblages, lockdown iPhone shots of household items with a sinister edge. A bloodstained knife alongside a Saint Laurent condom; a cigarette resting on a camera’s hard case. Then follow a pair of Tyson Ballou portraits, the Texas-born model clad in black leather, as if guarding the entrance to an illicit chamber of Steven’s making.

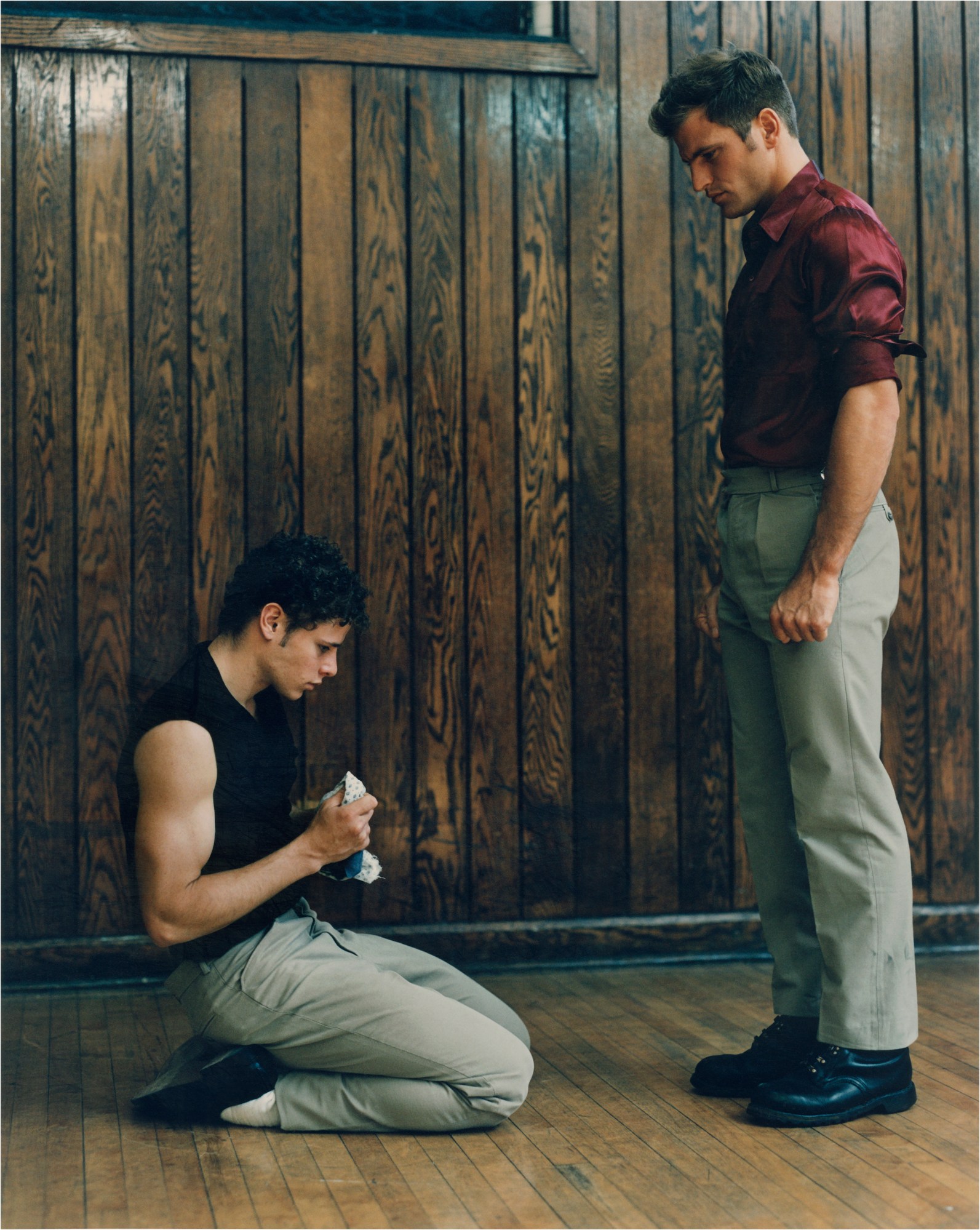

Editor Mark Holborn helped to sequence images from Steven’s magazine shoots into a coherent narrative, “a story that unfolds like a murder-filled movie,” he writes. A scarred Jodie Foster appears trance-like at a kitchen table, peeling potatoes for a W magazine shoot of Martin Scorsese’s leading women. Across the book, red meat and disfigured mannequins give a sense of contorted humanity, while muscular bodies recline in various states of tension, relaxation or bondage. There is the suggestion of pain, but rarely its confirmation. A man restrained by police looks ponderously towards the ground; when guns are pointed, they carry a strange majesty, the promise of injury both tragic and beautiful.

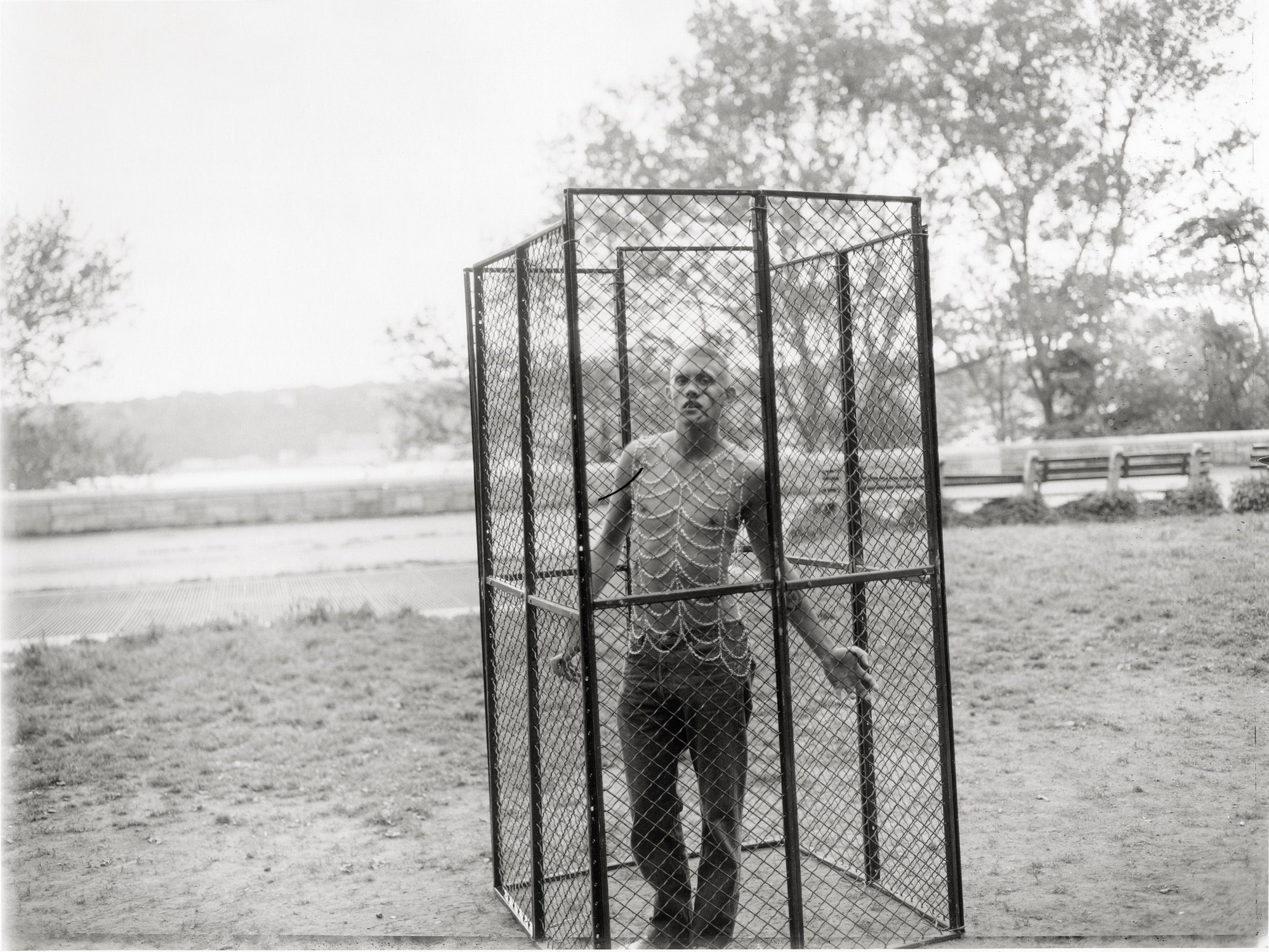

Madonna appears more than any other person in the book, their longstanding collaboration the best example of Steven’s method. The 2003 project X-STaTIC PRO=CeSS comprised an extensive shoot and exhibition of video, animation and sound work at Deitch Projects, New York, which Madonna then used to open shows on her Re-Invention world tour the following year (the stills have since been made into NFTs). The work explored desire’s shadowy corners, played out in a church-like room with three-dimensional sound. Steven’s photos included references to the Book of Revelation, gunshots, animal lungs and kidneys, all presented in a twisted carnival. As is common in his work, the action took place on beds, poles and cages, sites of Steven’s favoured dichotomies: love and injury, death and revival, stimulation and subjugation.

“I tried to see Madonna more as a performance artist than a pop star,” Steven says. “I take the element of celebrity out of the equation.” Instead of relying on a person’s fame, Steven views all his subjects as actors to be directed. When judging posture or lighting, they are reduced even further, to just bodies.

Bondage gear is part of a “constructed visual language” which allows him to push these bodies to extremes, he explains. “The body is inherently soft, and has a lot of curves. I always like to create tension and contradiction against that softness using hard lines.” In one shot, a woman in yellow underwear does a headstand in a cage; in another, Ashton Kutcher is suspended above a crowd, attached to a lamppost with gaffer tape. Everywhere you look, Steven works through entrapment.

Does this role-playing work with professional actors? One of Steven’s most renowned (and now infamous) shoots is 2006’s Domestic Bliss, a 60-page portfolio for W, in which Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie oscillate between suburban Americana (complete with five young children) and the glamour of a heated and volatile love affair. (Steven also shot Brad as Tyler Durden, mid-Fight Club filming). Brad wanted something in the style of classic LIFE magazine shoots, Steven remembers, the slowly unfurling, stylised treatment of the American imaginary. But selected for the book are the more violent images, Brad’s character pinning Angelina down on the bed, covering her mouth with his hand.

A similar air of threat surrounds Nicole Kidman’s character in a 2014 shoot. The figure lies curled on a long leather jacket, a twisted fence and red lighting creating a hyperreal sense of danger. “Shooting with actors is a great opportunity to work with talented people and use them for what they can do,” Steven says. This recasting has led to his subjects being seen in a new light after he’s worked with them, especially Justin Timberlake and David Beckham, whose 2000 Arena Homme+ cover reimagined the footballer as a showbiz asset.

But Steven’s ideas of truth and personhood lie elsewhere, in his nude model or close-up body studies. Rallying against the ideals of portraiture (“That a portrait is the truth, the eyes bring the window of the soul”), he created images of cut throats, prosthetic lacerations on icy skin. “The outer surface of the body is merely the clothing,” Steven says. “The idea of who somebody is, that’s their soul.”

He was inspired by Richard Avedon and Irving Penn, artists who “believed that their work showed a person’s inner truth”, while still breaking photography’s conventions. Richard’s 1957 image of Marilyn Monroe shows her looking vacant, “the inevitable drop…when the white wine was over, she sat in the corner like a child”, the late photographer recalled. That vulnerability seems to be what Steven is pursuing while self-consciously questioning psychological truth. Are the cut throats the culmination of his focus on destruction? “No, they’re not violent,” he says. “They’re about the idea of breaking through skin to get inside; to negate these ideas of realness.”

And yet, there is no blood without injury, no flesh without incision. Steven’s is a world of nudity and exposure, of physical bondage but social liberation. A model is no longer a model, a gun no longer a weapon, a cage no longer a punishment. All become tools for the manipulation and staging of bodies, those who wish to be recast without inhibition. Still, he speaks in mortal terms. “Photography is do or die,” he says. “If people don’t like the work, that’s fine, but at least do what you really feel is your vision, and what comes from your heart and soul.”

‘Steven Klein’ is published by Phaidon, £150 (Phaidon.com)

Credits

All images © Steven Klein. All Rights Reserved