“When I started Common Prayer,” Joan Didion told The Paris Review in 1978,discussing her landmark novel, “all I knew about [the character] Charlotte was that she was a nervous talker and told pointless stories. A distracted kind of voice. Then one day I was writing [the scene at] the Christmas party at the American embassy, and I had Charlotte telling these bizarre anecdotes with no point while Victor Strasser-Mendana keeps trying to find out who she is, what she’s doing in Boca Grande, who her husband is, what her husband does. And suddenly Charlotte says, ‘He runs guns. I wish they had caviar.’ Well, when I heard Charlotte say this, I had a very clear fix on who she was.”

He runs guns. I wish they had caviar gets us a very clear fix on Joan Didion, too — it’s a sharp and succinct pairing, violent and feminine; gritty but grounded in old-money mores. It’s basically Joan at her airiest, scariest. Though A Book of Common Prayer is set in the fictional Boca Grande, no two lines could be more unmistakably right-wing American. The book is far less popular than Play It as It Lays, perhaps because it nods at a different Joan Didion: one with more serious preoccupations outside hot ‘n’ hip female ennui. The novel is the story of two women: Charlotte Douglas, and Grace Strasser-Mendana. Its narrator is Grace, an anthropologist, who is married into a family of some repute and power in Boca Grande, its dreamed-up Central American setting; she is watching and recording the life of Charlotte Douglas, a woman whose daughter has disappeared, having run off with a group of Marxist terrorists. Famously, the opening and closing lines are a pair to each other, which goes to show that Didion really does live by her own big writing credos (commit to your first sentence; use the last sentence to make readers loop back and read from a different perspective): “I will be her witness,” and “I have not been the witness I wanted to be.” There is more to it than this, but since I am always hearing that I should not be including the full synopses of books as a way to ensure future readers’ enjoyment, I won’t divulge its complexities.

(Most of my Didion books are those old Penguin paperbacks that have the pithy one line-summaries. This one’s says: “The bestselling novel of Charlotte Douglas’s decline and fall.” I might have simply left my explanation there.)

Famously, the opening and closing lines are a pair to each other, which goes to show that Didion really does live by her own big writing credos (commit to your first sentence; use the last sentence to make readers loop back and read from a different perspective).

It’s been fifty years since the novel was published, which typically means that we — by which I mean the media — owe it an anniversary article. Happily, I am here to oblige: to bastardize its opening line, I will be its witness. I am, I’m certain, it’s millionth witness; though it isn’t one of her sexiest works, there’s still rabid millennial hunger for everything Didion.

Common Prayer is far more interesting for some of the changes it marks in its author — or in its author’s works; though aren’t these, truly, almost the same thing with Didion, who is so frightfully stylish and stylized? — than for its content or quotable passages. It is perfectly written, of course. There is always a trance-like loveliness to Didion; always that smooth sentence rhythm that I’d liken to the lull of riding a moving train; always the neatest of nearly-meaningless, half-profound aphorisms: “We all remember what we need to remember.” When I point out that these aphorisms are meaningless, please understand that I say this admiringly, or at the very least near-admiringly. This is a hard piece of sleight-of-hand to pull off, as any writer with a looming deadline knows: writing about nothing and making it seem like something is most of our figurative bread and butter.

Christian Lorentzen wrote, for New York Magazine a couple of years ago, a tremendous long-form look at Didion’s various selves, from the pretty and pop to the political. In it, he refers to “Joan the novelist, who remains in print but is read only by completists whose completist tendencies might bring them through Run River and Play It as It Lays, even A Book of Common Prayer” — the emphasis, one assumes, on the “even.” Prior to this, Joan Didion had been earning a reputation as a writer of “women’s stories,” with all of these women in these stories, to some degree, being Joan Didion. “That kind of [personal] writing is limiting,” she told Hilton Als in 2004, thinking how she arrived at the terror-tinged plot of A Book of Common Prayer in the first place. “Another reason [I started to write about politics] was that I was getting a very strong response from readers, which was depressing because there was no way for me to reach out and help them back. I didn’t want to become Miss Lonelyhearts.”

Of course her readers — the Lonelyhearts women — had strong reactions to books like Play It as It Lays and essays like The White Album, seeing as both were essentially primal screams about damaged womanhood. Crucially, they were primal screams about beautiful, delicate damaged womanhood; stories about women, the fictionalized Didion and the real person respectively, who had managed to maintain a certain level of chill despite their great undoings. They were also set in California — arguably the most seductive American state, if not the most seductive place to set a story about a slow personal breakdown de facto. (Try to imagine Play It as It Lays’s Maria Wyeth being institutionalized in the drizzle in Leeds, or in Glasgow in the snow. You can’t! There are no hummingbirds in the picture, for one thing, to help her to keep herself occupied. Being nihilistic is tougher to stick with in colder climes, as it tends to feel even more miserable.)

“Charlotte, in Common Prayer,” Didion tells Als in the same conversation, “was somebody who had a very expensive dress with a seam that was coming out.” Likewise, Didion herself was — according to Caitlin Flanagan, writing forThe Atlantic — at one time, a woman “who went to the supermarket in an old bikini and boarded first-class compartments of international flights in bare feet, and who therefore — because she thought about things always on her own terms — could see things in front of us that we’d been missing all along.” The wasted glamour is still present; what we have, now, are politics served alongside. Never mind that Didion herself had been spending her time in Salvador, rather than LA, while writing A Book of Common Prayer. These women are deeply immersed in a world that actually differs from Joan’s in the height of its stakes. When she writes “I am an anthropologist who lost faith in her own method, who stopped believing that observable activity defined anthropos,” you know it isn’t the character speaking; it’s Didion, who is the keenest writerly observer and is, at this time, the writerly observer tortured most by her own choice of observations — observations, for instance, about “hang[ing] fifty yards of yellow theatrical silk across the bedroom windows,” or “Blue-and-white striped sheets. Vermouth cassis. Some faded nightgowns which were new in 1959 or 1960, and some chiffon scarves.”

There is nothing wrong with an interest in blue-and-white bed-sheets and chiffon scarves — it’s why a great swathe of eager chick readers love Didion. But most femme-identified personal essay writers — especially now, in an age about which Nell Zink wrote for Lithub that “it has often been said: ‘the internet is female'”— find themselves with the same dilemma. Joan has not lived through the age of It Happened to Me as a young person; but we know all about what was Happening to Her in her youth as a consequence of her essays, anyway. “One difference between the Didion of the early 70s and the Didion of the early 80s,” Lorentzen points out, “is that in the 70s she wrote about sitting on the beach in Hawaii, thinking about the body counts in Vietnam, because her editor at LIFE wouldn’t send her to report on it herself.”

Maybe most telling of all is a hefty chunk in her Art of Fiction interview where she talks about Common Prayer‘s structure and politics: “Sometimes you can get away with things in the middle of a book… Common Prayer had a lot of plot and an awful lot of places and weather. I wanted a dense texture, and so I kept throwing stuff into it, making promises. For example, I promised a revolution. Finally, when I got within twenty pages of the end, I realized I still hadn’t delivered this revolution. I had a lot of threads, and I’d overlooked this one. So then I had to go back and lay in the preparation for the revolution. Putting in that revolution was like setting in a sleeve. Do you know what I mean? Do you sew? I mean I had to work that revolution in on the bias, had to ease out the wrinkles with my fingers.”

It’s so deeply Didion to wax insane about the weather and the scene, and to almost forget the damned revolution: here, the difference is that she finally works it in. Joan, the woman who wears no shoes to fly, with her gimlet eye, is never unaware — Plath’s declaration of being “catastrophically aware,” in fact, might have been meant for her. The idea of seeing oneself being pigeonholed and then, perhaps against type, course correcting is sort of delicious. You think you know me? Think again! It’s probably why I unthinkingly name-checked Didion in the thing I wrote about the discrete charms of Chloë Sevigny; both women offer up their perfectly perfected styles, and somehow everything and nothing of their interiors simultaneously. I know that Didion holidayed in Hawaii “in lieu of filing for divorce” because it fits her narrative, but I’ve no idea about her more mundane behaviors: the real, quotidian Didion. Privacy is a relative luxury rather than a fundamental right for a female internet writer who ends up forced into what Slate calls “the first-person industrial complex” — Lonelyhearts fanatics evidently number even higher than Joan Didion imagined. Fifty bucks for the heartfelt story of a miscarriage has always seemed, to me, like a certain miscarriage of justice, which is why I understand why — even then — the queen of the Lonelyhearts desired so badly to turn herself into a new kind of writer. Turning to politics was as if she were joining a rebel faction herself.

Read: Exploring what makes Céline’s Juergen Teller-shot campaign images of Joan Didion stand out.

Credits

Text Philippa Snow

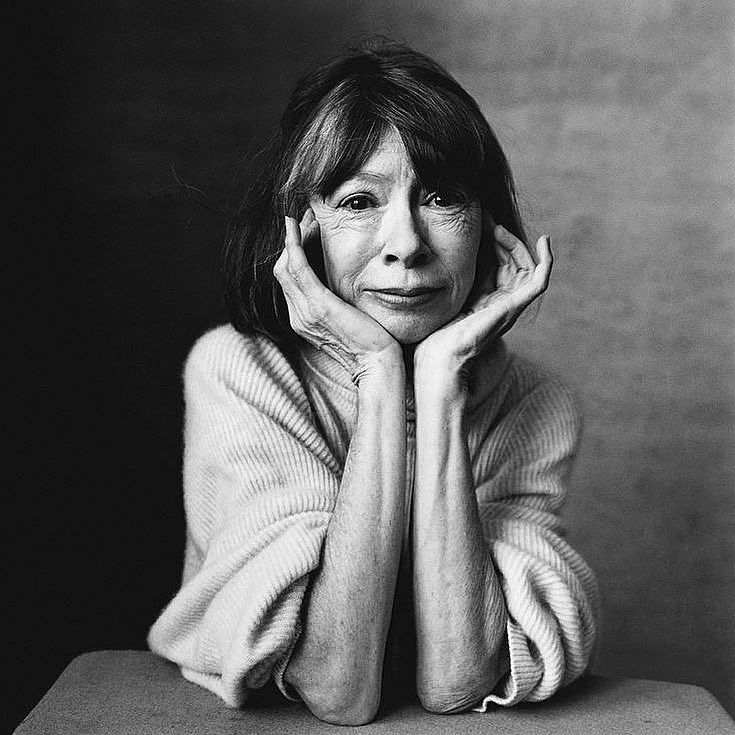

Image via Flickr