Over a period of eight months, Nazi Germany embarked on a massive bombing campaign known as the Blitz that reduced London to shambles. Between 1940–41, some 43,000 people were killed while 1.1 million homes were destroyed, reducing many corners of the city to rubble. Following the war, the nation called upon the people of colonised nations to help it rebuild, and between 1948 and 1971, an estimated half-million people emigrated to the UK.

As London regained its stride during the Swinging Sixties, the far right began a coordinated attack against those who put the country back on its feet. In 1967 AK. Chesterton founded the National Front, a neo-fascist political party that called for the end to non-white immigration, stripping non-white Brits of their citizenship and segregation, espousing antisemitic rhetoric, and opposing feminism and LGBTQ rights. The following year, MP Enoch Powell delivered the incendiary “Rivers of Blood” speech in Birmingham, using racism as a weapon in a war against the working class.

As the UK spiralled into economic decline during the 1970s, the NF reached a fevered pitch, playing on racism and xenophobia to gain power and influence. “It was the beginning of the first major recession since the war. Times were getting incredibly rough, especially for the working class,” says Australian photographer Syd Shelton, who had arrived in London in 1976. “At the behest of the International Monetary Fund, the Labour government and Prime Minister Jim Callaghan imposed incredibly stringent cuts, and things became tougher for loads of people, almost exactly like what’s happening now. As in the 1930s, it gave rise to horrendous scapegoating where people started pointing the finger at immigrants — Black, Irish, Chinese — whatever difference became a spurt of political activity.”

Under the leadership of Martin Webster, the NF began campaigning for council seats while organising marches through Afro-Caribbean and South Asian communities across the UK. “It was a ragbag bunch of Nazis, and their slogan was, ‘If they’re white, they’re alright. If they’re Black, send them back,'” Syd says. “Just like the Nazis in Germany, they had started to become violent, and they knew that they would have to win street battles to build a cadre of young supporters. They started putting on fantastically intimidatory marches through successful multicultural inner city suburbs like Woodgreen and the West Midlands.”

Tensions came to a head on the 13th of August 1977, when the NF staged an “Anti-Mugging March” from New Cross to Lewisham in South London. The police sent 5,000 officers, including the Cavalry Division, to escort members of the NF through the streets and “protect” them against some 4,000 counter-demonstrators who arrived to protest the march. The police armed themselves with riot shields for the first time in mainland Britain, making it abundantly clear which side they took.

Faced with a standing army, the battle lines of the counter-protest were redrawn. “There were many scores to be settled with the Metropolitan Police,” Syd says. Outnumbered, NF members quickly fled as skirmishes between protesters and the police began, culminating in a massive melee known as the Battle of Lewisham. Police charged their horses into the crowd, wielding truncheons against unarmed counter-protesters. Syd stood at the frontlines with his camera, documenting a definitive defeat for the NF just four miles from where Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists lost the 1936 Battle of Cable Street.

Although the battle had been won, the war raged on as the NF continued its campaign to infiltrate the government as wholesale racism went mainstream. “The National Front developed an electoral strategy where it was unclear who was financially backing them, but they had enough money to put candidates into most of the constituencies in the general elections,” Syd says. “They saw they could build their party with local council elections in particular. Things were also starting to get very scary on a much more mundane level. A minstrel show was the prime Saturday night TV. There were signs in windows that said, ‘No Blacks, no dogs, no Irish.’ Racism was being normalised, and anti-racism was a dangerous position to take.”

The breaking point came on the 5th of August, 1976, when Eric Clapton paused his Birmingham concert to make a speech of his own. He asked immigrants to identify themselves and then lashed out. “I don’t want you here, in the room or in my country,” he said, sprinkling his racist slurs through his rant. “Listen to me, man! I think we should vote for Enoch Powell. Enoch’s our man. I think Enoch’s right, I think we should send them all back. Stop Britain from becoming a Black colony. Get the foreigners out…. Keep Britain white. I used to be into dope, now I’m into racism. It’s much heavier, man.”

In that moment, Eric Clapton exhibited a lack of self-awareness as grotesque as his bigotry. “This man built his career on Black music,” Syd says of the guitarist who coopted the blues for fame, status, and wealth. “It absolutely horrified a group of people, in particular a photographer named Red Saunders. He, together with the Magic Box Theatre Group and others, wrote a letter to the music and left-wing press calling for a rank and file movement of musicians and fans called Rock Against Racism [RAR].”

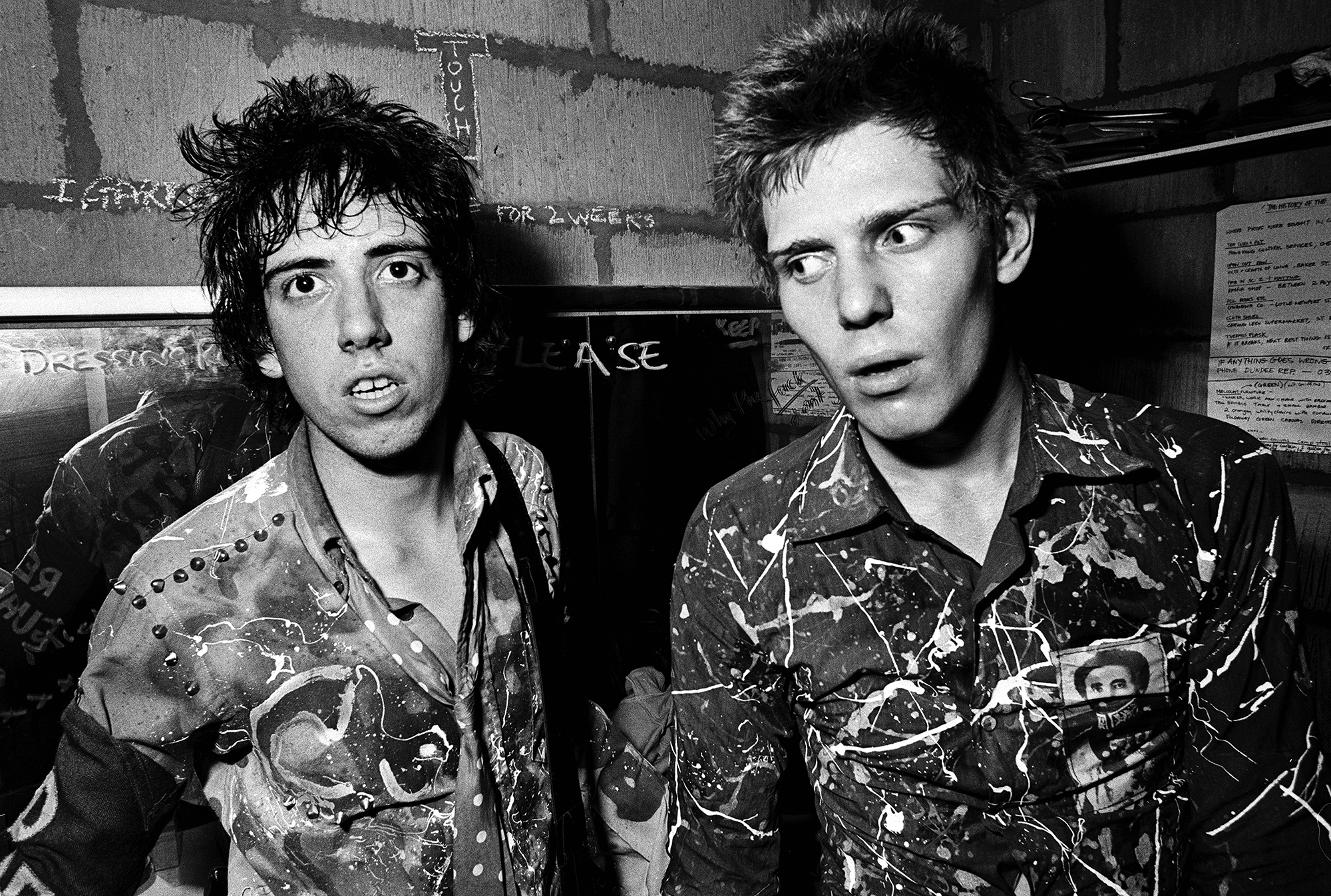

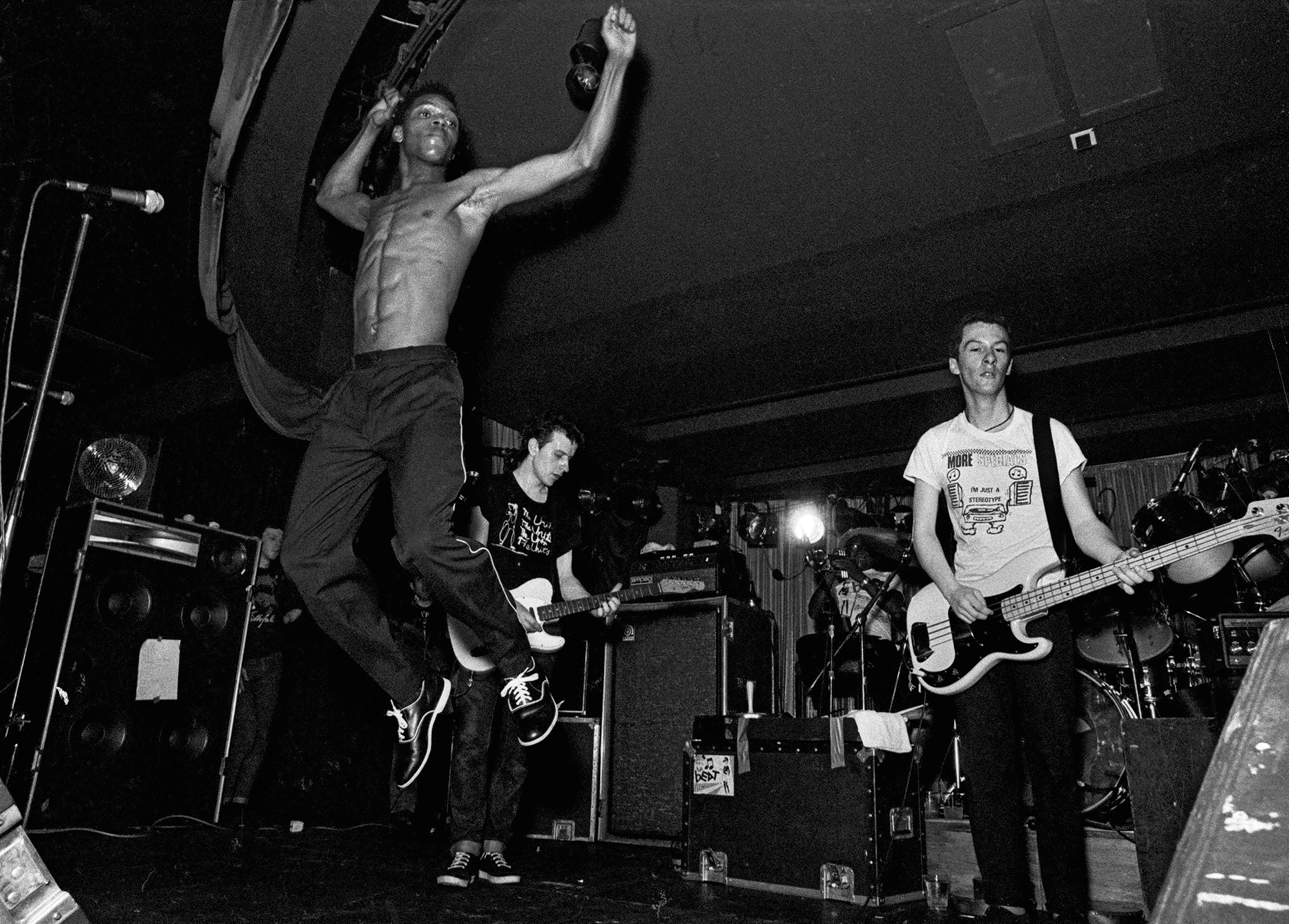

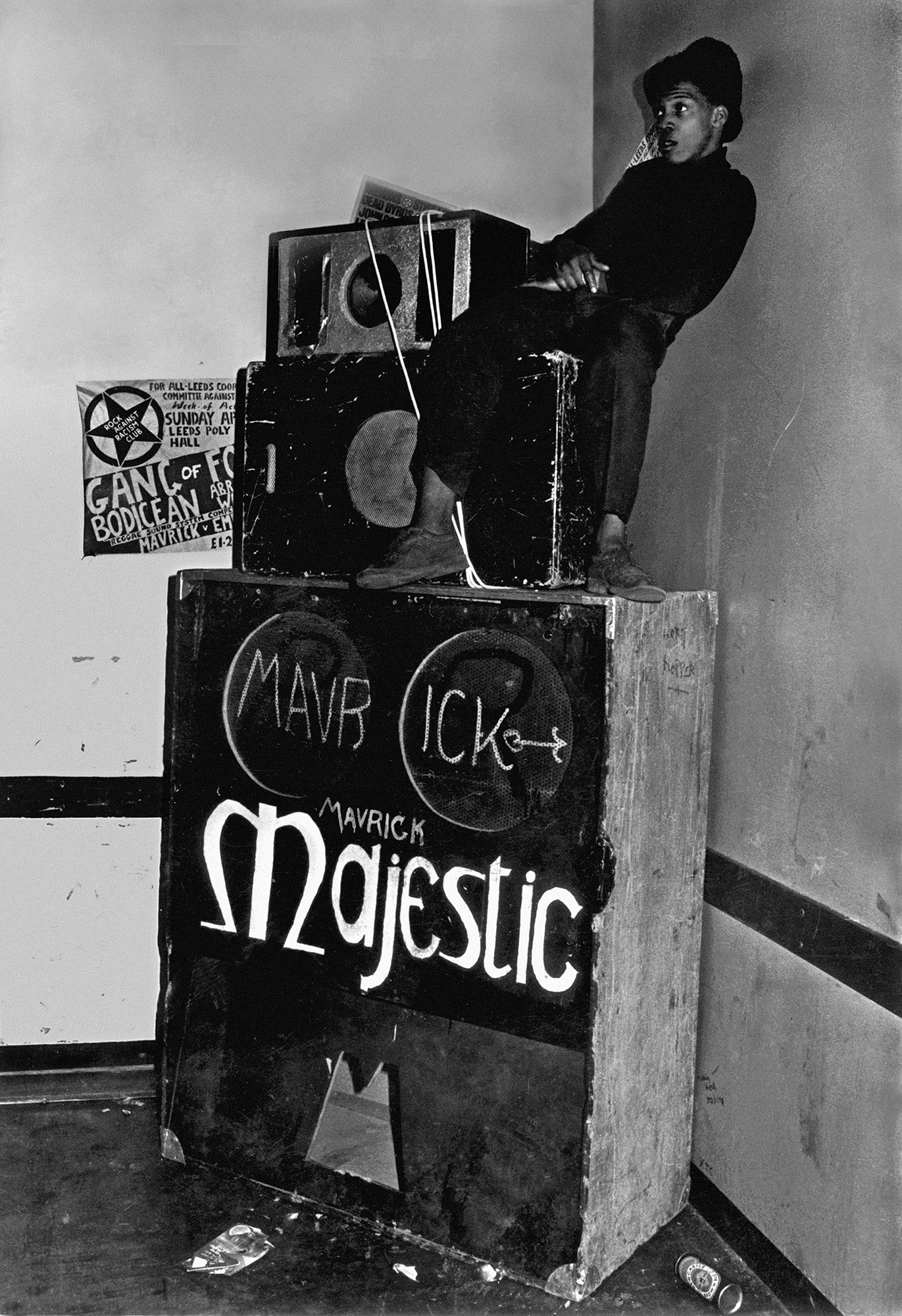

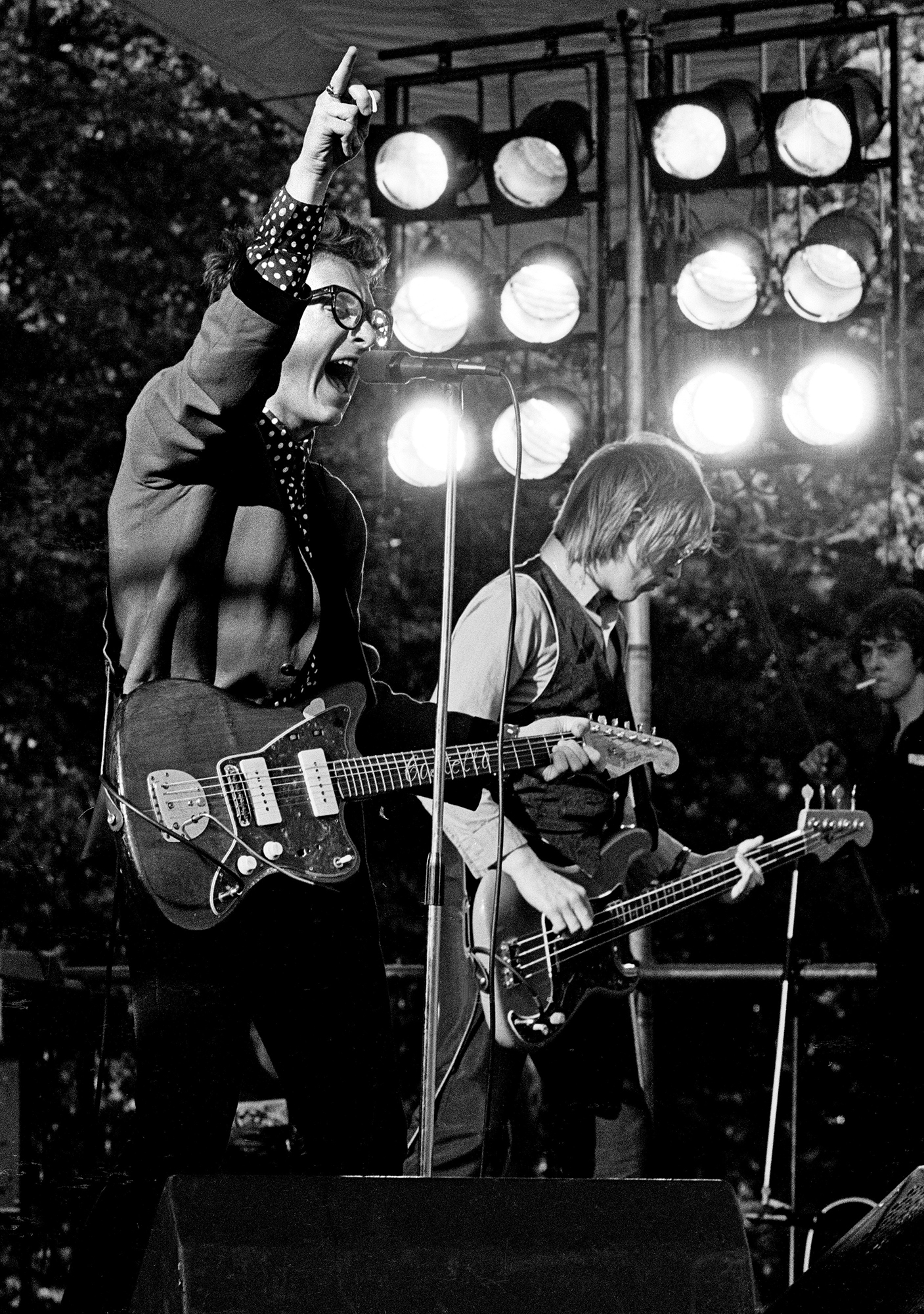

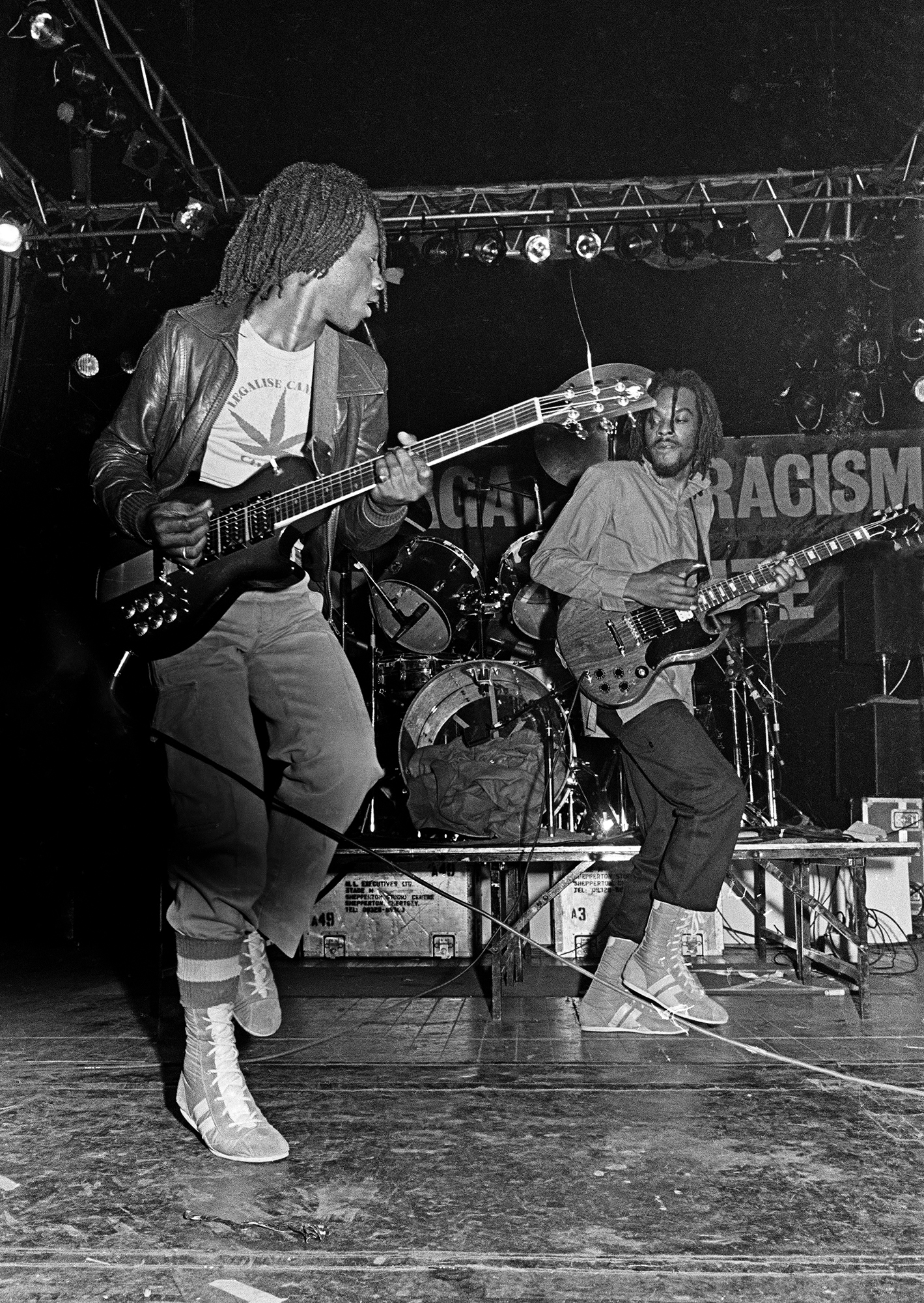

RAR emerged at a potent time in the nation’s counterculture movement, just as punk and reggae took hold, both powerful forms of rebel music in their own right. With bands like The Clash, Steel Pulse, X-Ray Spex, Aswad, and The Specials sharing the stage, RAR brought together Black and white audiences for the first time. RAR worked with musicians, activists, and organisations to successfully turn the tide against the National Front. Four decades later, Syd revisits his archive to look back at this historic movement for change in the new book, Rock Against Racism Live. 1977–1981 (Café Royal Books) and shares a wealth of hard-earned wisdom all the more pertinent today.

Embracing the DIY ethos of the times, RAR had a small committee at the core that was determined by who regularly turned up at meetings rather than by a formal election process. “There were about eight or nine of us who were there for the whole journey,” Syd says. “We didn’t know what we were doing, but we were ambitious and felt empowered by the explosion of an anti-racism movement. It wasn’t some horrible drudge of a job, it was fun, and we all wanted to go to gigs and see all of these bands. The organisation had a mixture of people on the left with quite different perspectives. Some were members of the Socialist Workers Party, others weren’t members of anything, but what united us was that we all loved music and we were anti-racist.”

The first major RAR carnival was held on the 30th of April, 1978, at Victoria Park in east London. “The National Front had gained 17% of the vote in the Greater London Council election in that area, so we held the event the day before the next council elections,” Syd says, who was living in Charing Cross Road at the time. His assignment was to organise the people arriving in Trafalgar Square for the start of a massive march to the park.

That morning, he awoke early and headed downstairs, only to find some 10,000 people had gathered and were raring to go. Bands like Misty in Roots, The Mekons, and The Piranhas boarded a fleet of flatbed trucks that led the crowd seven miles across London to the park where The Clash, Steel Pulse, and The Tom Robinson Band took the stage. “We wanted to do the anti-racism Woodstock, something serious. We took over London that day. People noticed because there was music from one end of the city to the other,” Syd recalls.

“Everybody was there. When Billy Bragg was doing his book, he asked if I had any photographs of the Gays Against Nazis because he was standing near them. We couldn’t find a picture of him, but we did find a banner for the group. Billy said that when Tom Robinson started singing “Glad to Be Gay,” all the guys in the group started kissing each other, and he wondered, ‘What is this?’ He was only 16 or 17 at the time. On his way home on the tube, Billy said the penny dropped. He realised the Nazis would be against them as well. Then he said, ‘That was the day my generation took sides.'”

The RAR action had an immediate effect. “The next day at elections, the NF went from 17% to less than 1%,” Syd says. “It led to the summers of carnivals in Edinburgh, Manchester, and Brixton; we spent the whole summer organising these massive carnivals with great marches beforehand. Over five years, we sold something like three million badges, which was the way we funded most things. We also had a fanzine called Temporary Hoarding that ran for 14 issues.” The gig guide provided guidance to people wanting to get involved, giving them the mechanics of producing a show so that they could pick up their cudgel in their corner of the country.

“Rock Against Racism led to the formation of the Anti-Nazi League in 1977, which was aimed at defeating the National Front in elections,” Syd says. “They had massive broad support from trade unions, Labour Party politicians, football managers, and famous athletes, which meant they had some financial clout. All of the carnivals were done jointly with the Anti-Nazi League, and the collaboration was crucial in the success of both organisations. We had our differences, and they saw us as the lunatic fringe. Our slogan was, ‘All power to the imagination,’ which they thought was completely out to lunch, but we worked well together.”

And that is the key to success. When trying to unite against a common enemy, infighting is the knell of death. “When people get together in solidarity and fight, we can change things,” Syd says. “But it’s important to recognise there is no ultimate victory; there is only struggle. Racism is not something you ultimately defeat because it’s going to be used by the right-wing as a weapon to divide people, so you have to fight it your whole life. Even though there were so many points of view in Rock Against Racism, what was important was what united us, not what divided us.”

‘Rock Against Racism Live. 1977–1981’ is out now via Café Royal Books

Credits

All images courtesy Syd Shelton