A fashion revolutionary in the truest sense, Vivienne Westwood blazed a trail unlike anyone that came before her. Acting as punk’s original outfitter, the Derbyshire-born designer defined some of pop-culture’s most iconic moments, preaching cultural innovation over aimless consumption. Between the cheesecloth shirts of Johnny Rotten, the towering platforms responsible for Naomi Campbell’s legendary topple and runway shows as protests, clothing was Vivienne’s creative firearm.

Growing up during the rock and roll heyday of the 50s, Vivienne toyed with fashion design since age 14. “It was the most incredible time because it coincided completely with me being a kid, turning into a woman. There we were making clothes. We were where it was at. That was rock and roll. I was there,” she said in 2016. However, fashion wasn’t always on the cards. Starting her career as a primary school teacher in North London, Vivienne moonlighted as a jewellery designer on Portobello market until meeting art-school sweetheart, Malcolm McLaren. By 1971, the duo had set up shop on the King’s Road, and the rest is fashion history. “He was four years younger than me. At a certain point, he wanted to rework the 50s, so I knew what to do.”

From there, Vivienne would design her own garments with Malcolm, before later taking the plunge into capital-F fashion when the store’s lease stopped. “I decided to carry because I was good at it,” she remembers. “I thought it was my duty.” Here, her designs were first mocked and later applauded for their studious socio-political commentaries. Nowadays, you’d be hard pressed finding a fashion course without her work in the syllabus. After all, she’s responsible for an epoch of fashion activism, confronting corruption and climate catastrophe through her work.

Of course, for all her political integrity, she remained an eternal source of humour and ebullience. Whether it was through miniature crinolines, bondage trousers or her pirate boots, Vivienne rerouted fashion’s trajectory, a legacy safe in the hands of husband and collaborator, Andreas Kronthaler. To mark the passing, we chart some of her myriad milestones.

Teds and Punks

Known today as Worlds End, Malcolm and Vivienne’s shop opened as Let It Rock on 430 King’s Road, a hallowed location already steeped in subcultural capital after running as designer Trevor Myles’ Mr Freedom and Paradise Garage. Then, it was a hotspot for London’s 1960s counterculture, but under Malcolm and Vivienne’s flights of fancy, it became the go-to for budding teddy boys, replete with 1950s-style clothing and décor. “The Kings Road was like the centre of fashion for the world,” remembers Michael Costiff, who amassed over 300 Westwood pieces with his late wife Gerlinde. “I knew them from the day they moved in – Vivienne sat in the back on a sewing machine with a jukebox playing. They were just another couple having a go.”

Always concocting new ideas, the duo continuously changed the shop’s name and theme. Let It Rock became Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die in 1973, a biker gear specialist, before changing again in 1974 to Sex, a kinkster’s paradise lined with latex and gas masks. Manned by the infamously intimidating shop girl, Jordan, Sex attracted a hotchpotch clientele of fetishists and fashionistas alike, sowing the seeds for punk.

By 1976, it adopted the name Seditionaries, taking tropes of its sexy past – bondage, in particular – and riffing on them to create the archetypal punk look. Tartan bondage suits became synonymous with the store, as did its biggest co-sign, the Sex Pistols, who rocked the Swastika- and nudity-emblazoned garb in their fabled interview that got Bill Grundy banned from British TV.

Pirates and Witches

Eventually, Vivienne became disillusioned by punk. The Pistols had split up, and a new, flamboyant scene was spawning. “The New Romantic scene was happening at the end of the 70s and a lot of people that were in the punk scene evolved their looks,” recalls DJ Princess Julia. “Around 1978, the Blitz Club started, and it set the scene for the 80s to erupt.” Naturally, Vivienne had cottoned on, and, by 1979, entered another chapter in the shop’s story, renaming it Worlds End. While Malcolm immersed himself further into music, Vivienne held fort, dialling back the punk and setting stage for her first foray into high fashion.

For her debut collection, AW81-82, Vivienne plundered the history books, calling on cuts from the French Revolution and seafaring buccaneers. Entitled “Pirates”, the swashbuckling style was distinguished by chisel-toe pirate boots, felt admiral hats and fall-down stockings. A development from the New Romantics, the look was soon adopted by McLaren’s client, Adam and the Ants, who would frequent Worlds End. Following up for AW82-83 with the Buffalo Girls (Nostalgia of Mud) collection, an ode to Ray Petri’s rebellious “buffalo” style, Vivienne resumed her anti-fashion approach, cementing house codes in bizarre silhouettes, “squiggle” prints and salvaged materials.

Then came the AW83-84 Witches collection, fashion’s first Keith Haring collab, complete with fluorescent graffitied skirt suits and witch hats aplenty. Even then, Vivienne’s work was still beyond the mainstream’s recognition, but years on, these pieces from Witches attract auction prices of up to £36,000. That said, by SS85, anyone worth their sartorial salt would surely see Viv was onto a winner. Applying the Victorian crinoline to mini-skirts, Vivienne birthed the “mini-crini”, an embodiment of her postmodern blend.

Tweed, Tartan and Topples

Vivienne continued to tinker old designs well into the late eighties, especially in her Harris Tweed AW87-88 collection. Inspired by a chance encounter with a young girl dressed in a Harris tweed coat and ballet shoes, Vivienne cut the otherwise conservative staple with Savile Row precision to create suiting, winter-proof mini-crinis and crowns, completing the look with her signature rocking-horse shoes. “Using Harris tweed wasn’t fashionable,” says Westwood collector, Steven Philip. “But Westwood subverted and played with the idea Britishness, using British institutions, public school uniforms and the royal princesses as inspiration.”

Catching wind, fashion journos coined yet another style tribe for Westwood’s roster, the “Tatler” girl (think eighties Tory with an edge). The irony was not lost on Viv, though, who later posed as Margaret Thatcher for Tatler’s April 1989 cover with the headline, “This Woman Was Once a Punk”.

Indeed, in mining tradition, Vivienne balanced convention and subversion to reflect a moment. Take her use of corsetry. Once the material embodiment of a woman’s subjection, Vivienne turned it into an outerwear staple, revitalising it with Rococo designs for her AW90-91, before giving it a gold, lurex makeover in her Anglomania AW93-94 collection. Add to this her own signature tartan, McAndreas, and those impossibly tall platforms that put Naomi on her arse, and you have the recipe for a British zeitgeist.

Noughties Gold

While Viv embodied gritty British rebellion, she also held sweetheart status in the US. Yep, far from the spit-flecked antics of punk, Westwood’s couture designs won over Sex & the City’s Carrie Bradshaw. After posing for Vogue’s annual age issue in a series of haute couture dresses, styled by André Leon Talley and shot by Patrick Demarchelier, Bradshaw was cruelly tasked to pick one for her big day. But, just like that, Viv couriered a dress directly to Carrie’s brownstone apartment with a note that read, “Dear Carrie, I saw your photo from the Vogue shoot. This dress belongs to you.” The dress in question? None other than am AW07-08 gold-backed, ivory silk number.

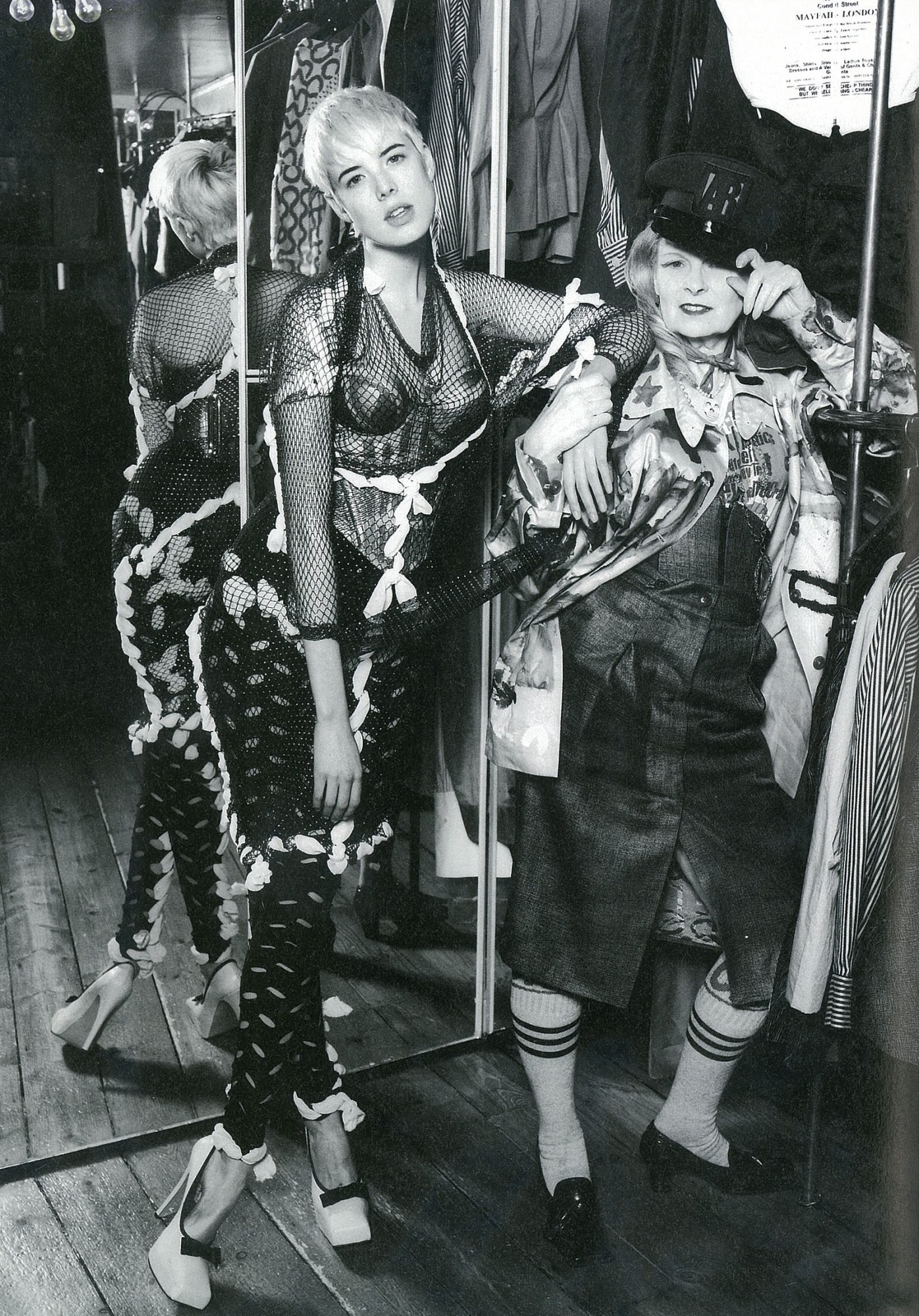

Meanwhile, across the pond, our chip-shop-girl-turned-indie-sleaze-queen, Agyness Deyn, seared Vivienne’s name into Y2K folklore, interviewing her in Worlds End for a dedicated Agyness Deyn-themed i-D issue. The two Northerners went at it in a fruitful conversation spanning climate change and literature, a moment Vivienne Westwood brand manager, Stuart Halton, was lucky enough to witness. “The interview took a lot longer than expected,” says Stuart. “People had to leave. The day ended with just me, Agyness and Vivienne alone in the shop finishing the interview and gossiping.” He continues, “I wasn’t mad about school. I always say Vivienne was the best teacher I ever had; the most important lesson was to question everything.”

Fashion as Protest

True to Stuart’s word, Vivienne spent her last years tackling fashion’s climate crisis and entwinement in capitalism head on. At her AW14 menswear show, she did so by slicking models’ hair so generously that it resembled the feathers of an oil-stained duck, an urgent call to the dangers of fracking, which her show notes made explicit. “Attention: Fracking is the Big Fight,” they read. “In England we must all challenge the irresponsible behaviour of our governments who are trying to force fracking upon us with no consideration of alternatives.”

Later, protest took a turn for the literal when Viv closed an otherwise conventional fashion show for Red Label’s SS16 collection with models wielding placards that read, “Fracking is a crime” and “Austerity is a crime”. She’s had been spreading these ideas since the late noughties when she launched her Active Resistance to Propaganda manifesto in 2008 at Serpentine gallery, and it’s continued since.

From captaining a tank through David Cameron’s village to orchestrating her SS19 campaign around the slogan “Buy less, dress up”, Vivienne never stopped fighting. Now, her company’s Instagram acts like a switchboard for young activists who want marches and major fashion moments in one scrapbooked place. It’s refreshing in an age of wipe-clean fashion Instagrams, ringing true to her punk legacy. No, punk’s not dead, it’s just changed for a new political juncture, a point echoed by Vivienne’s former design assistant, JordanLuca’s Luca Marchetti: “She demonstrated to me, through her dedication to herself and her own cause that punk is a philosophy and a way of thinking.” Long live Viv.