While the jury may still be out on what, exactly, sustainable fashion is, one thing that we can all agree is a positive step along the fashion industry’s path towards a more responsible future is the recent boom in upcycling. By turning one person’s trash into another’s treasure — luxury houses like Marni, Stella McCartney and Balenciaga have given real clout to what was once overlooked as a crafty trend.

Great as these heavyweight endorsements may be, it is — as is so often the case — among grassroots, independent designers that we’re seeing some of the most innovative and exciting approaches to the responsible design practice. Building their creative processes around upcycling from the get-go, designers like Stockholm-based Ellen Hodakova Larsson, Paris-based Benjamin Benmoyal, and London-based Alexandra Şipa are expanding the horizons of what upcycling looks like, turning everything from old uniforms, cassette tapes, and electrical wires into eminently desirable clothes.

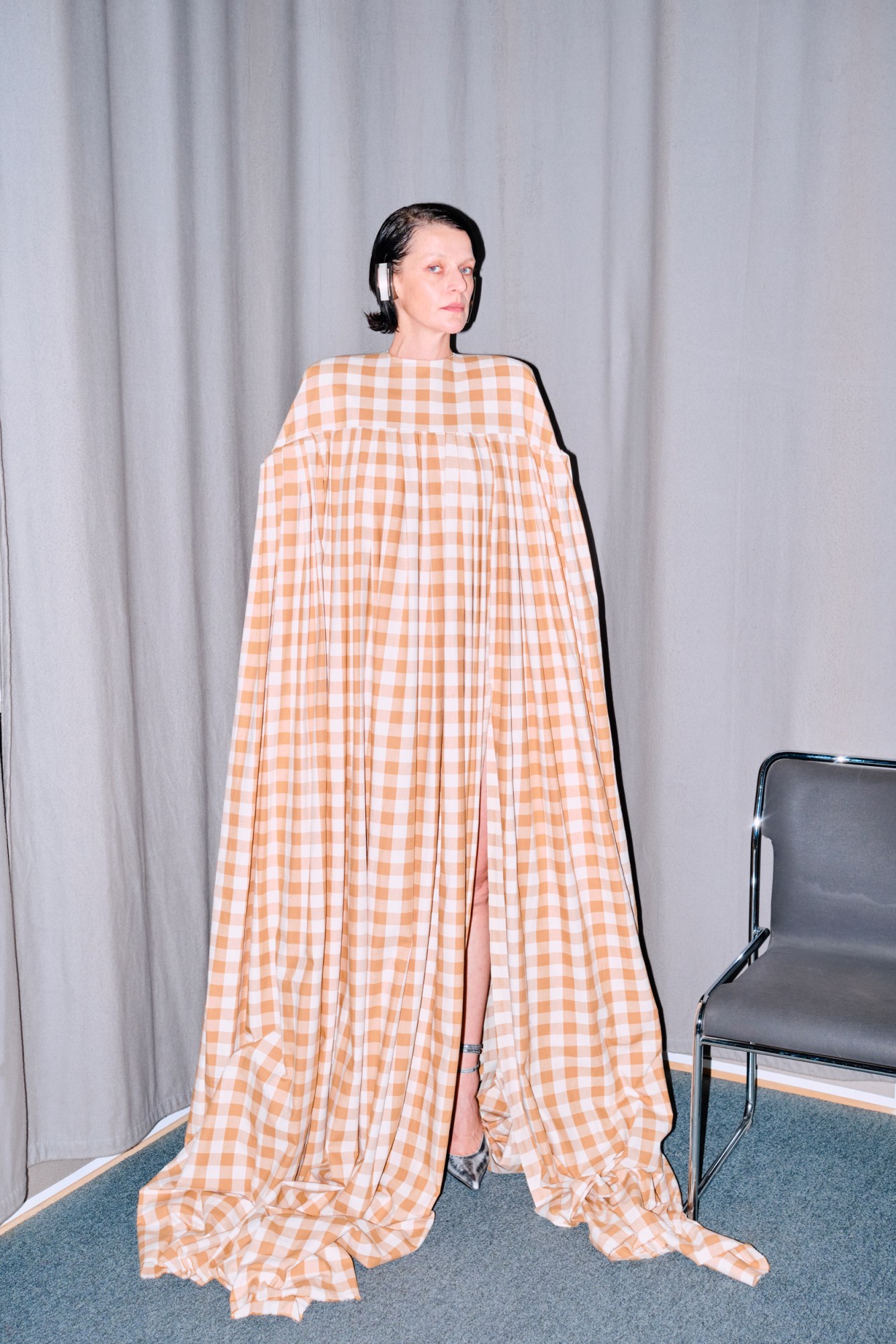

Ellen Hodakova Larsson

Ellen graduated from the Swedish School of Textiles in 2019, launching her label, HODAKOVA, soon after. “Built around moments of surprise and recognising the potential of the conventional,” her work riffs on quotidian clothes and fabrics to create one-off garments that subvert expectations of what they ‘should’ be. The waistband on jeans becomes an off-shoulder denim jacket; the lining of a pinstripe blazer becomes a wing-shouldered sleeveless dress. “I like to see my work as a study that sits between expectations and understanding,” she says, “one where the wearer and observer also get involved in the design process with questions.”

What are your main aesthetic influences? And how do the materials you work with direct your aesthetic?

I grew up with stereotypical uniforms around me, and what I find today is that there is a certain timelessness to the traditional menswear wardrobe. They’re clothes that are connected to the idea of expectations. When I get surprised in the process of making, I stop. In terms of aesthetic, I’m always influenced by music and lyrics, art and architecture. I want a pair of suit pants to play the same role as a feat of architecture — but worn on the shoulders.

What first inspired you to work the way you do?

My family has been the best support in enabling me to pursue my work with curiosity and fearlessness. Both of my parents are ‘doers’. They always repair what is broken and create with what they have around them for their fulfilment. This sense of valuing what exists and what you can create with it using your imagination was passed on to me, I guess! It’s almost like an ideology that is really process-focussed. My mum is also a great seamstress, and the attic of the farmhouse my brother and I grew up in was always filled with clothes.

You’ve made upcycling and recycling part of your brand from the start. What are the main challenges you’ve had to navigate?

It is a new challenge every day, but we all know that challenges are what make you evolve. For example, one of the things we struggle with is grading the designs, but I’m sure we will work it out. It is definitely an exciting path to be on.

How do you see yourself growing your business, and what does a sustainable business model look like to you?

[Goals] that focus on people’s health, the environment’s health, and sustainable healthy growth. Digital evolution is, of course, also part of that growth.

Benjamin Benmoyal

Benjamin graduated from Central Saint Martins in 2019 and worked at Alexander McQueen and Hermès before setting up his eponymous label in 2020. For AW21, he made his Paris Fashion Week debut, presenting a collection of garments created from deadstock and custom-developed fabrics woven from an unexpected material: discarded cassette and videotapes. While the bright, shimmering drapes that define Benjamin’s aesthetic may seem effortless, reaching the end result required him to reconfigure looms to work with the tapes as they would with normal yarn. Counter to what you’d expect from clothes woven from plastic film, he describes the end product as “soft, lightweight, easy to wear, to iron and washable.” Pure fashion alchemy!

What are your main aesthetic influences? And how do the materials you work with direct your aesthetic?

I draw inspiration from my Moroccan origins, focusing on volumes and drapings from traditional outfits — especially the ones worn in the south of Morocco during the 30s. They actually made clothes without making patterns; instead, they draped huge squares of fabrics, attaching them with gold thread. That’s why most of my garments are drapes of assembled squares, and the colourful striped woven fabrics are reminiscent of Berber crafts aesthetics.

Could you give us an insight into what your material sourcing process look like?

We work with two types of fabrics. There’s our own woven fabric, the main element of which is cassette tapes — and we need a LOT of them. We start by gathering thousands of kilometres of cassette tapes, aided by recycling charities, as well as by collecting the deadstock of factories that closed in the early 2000s. We then select deadstock yarns and combine them with the cassette tapes to create these colourful stripes.

We also work with upcycled fabrics. All the garments that are not made with our signature cassette tape fabric are made with deadstock from LVMH Maisons. They have thousands of unused and unwanted luxury fabrics, and we buy them for much cheaper than they would otherwise be. It’s a win-win!

You’ve made upcycling and recycling part of your brand from the start. What are the main challenges you’ve had to navigate?

The main challenge when you use upcycled yarns and fabrics is limited stock. But you learn to deal with it, as well as tricks to make it work. It took me years to source all these cassettes, but now I receive cassette tapes from different people almost everyday. I don’t even have any space left in storage for them!

Alexandra Şipa

Alexandra graduated from Central Saint Martins in 2020, founding her eponymous label soon after. For AW21, she made her London Fashion Week debut, presenting a bright collection that harnessed “the joy of Eastern Europe,” she says. Born and raised in Romania, she notes how “in fashion, the darker, moodier side of Eastern Europe is the better-known side of my culture.” Instead, she wants to show something a little bit different: “an undying hope and humour that can be found there.” Working exclusively with recycled and upcycled fabrics, the most striking aspect of her work is the bright handmade lace made with discarded electrical wires. Truly electrifying stuff!

What are your main aesthetic influences? And how do the materials you work with direct your aesthetic?

My influences are rooted in post-Soviet teenagehood and Romanian kitsch. There is a feeling I go back to a lot: the simple pleasures of being young in Romania, drinking with your friends, skipping school on a sunny afternoon in May.

I’m inspired by the contrast between heightened austerity and extreme femininity in Romania, and I explore clothes that pull you into two directions: sensuality and alertness, impulsivity and timidness. From the 18th century Turkish and 20th century French influences to the brutalist, communist and modern glass buildings; in Romania, nothing blends in. Nevertheless, the women are very careful about the way they look, getting all dressed up for a supermarket trip and loving an ultra-glamorous, ultra-feminine look. Through design, textile development and garment construction, the clothes reflect contemporary Romanian spaces in their apparent oxymoronic essence, seeking to find harmony in the discordance.

What first inspired you to work the way you do?

In a way, new fabric always intimidates me. I prefer finding and using things that have a past life. I have a tendency to rush when I work, and that’s when mistakes happen. With regular fabric, it’s harder to fix mistakes, but when I make the wire lace, I have so much freedom in the making process. I can undo; I can add; I can make things up as I go. The guiding principle of seeing waste as an opportunity to discover new techniques is at the heart of my brand. Also, around my second year at CSM, I read This Changes Everything by Naomi Klein, and this really opened my eyes to the severity of the environmental issues facing my generation. It made me feel like working this way is the only option.

Could you give us an insight into what your material sourcing process looks like?

For my debut collection, several of the materials used came from remnants and leftover fabric from my graduate collection. Due to the pandemic, it has been difficult to source vintage garments and fabrics, which I have previously found in charity shops and markets in London and Romania. Previous to the pandemic, I sourced electrical wires from an electronic waste recycling centre in east London. However, recently, I’ve purchased them from construction workers selling excess online. By rescuing discarded electrical wires, I attempt to address and bring awareness to the issue of electronic waste, one of the fastest-growing sources of waste, reaching 50 million tonnes in 2020.

How do you see yourself growing your business, and what does a sustainable business model look like to you?

I am slowly learning how to, one step at a time. As soon as I develop an idea, I think of how it can be sustainably produced. I wanted to have stretch pieces in the collection, so I found a company that prints on stretch fabric made out of recycled plastic bottles. When I wanted denim pieces, I sourced old denim jeans and repurposed them, and so on. All of the commercial discarded electrical wire lace pieces I make myself, by hand. Ethical production has been very important to me from the start, and I plan on producing the AW21 collection with a small, female-owned sewing studio in Bucharest. I won’t ever take orders that would require me to compromise the sustainability or ethics of the production process to fulfil. A sustainable business model considers environmental, economic, and social sustainability.