Sprawling some 1700 square km across Texas, Houston has become one of the largest cities in the United States, a far cry from its humble beginnings. Founded in 1836, Houston began as a mere 14.5 square km area divided into four wards; the first two for business and government, while the fabled Third and Fourth Wards were for residential use.

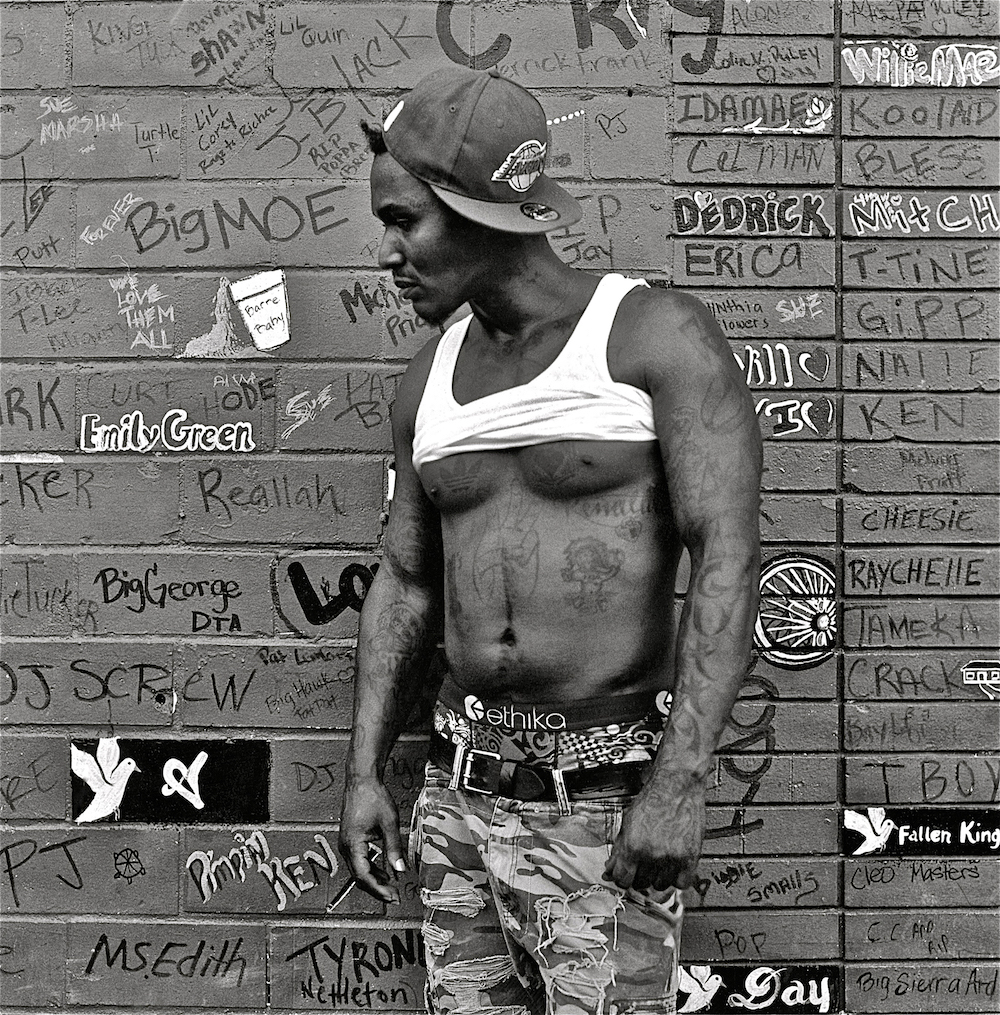

Although the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 freed the enslaved, those living in Texas weren’t freed until Juneteenth 1865 when the Confederacy collapsed and the Civil War came to an end. The following year, a thousand newly liberated Black men and women came together along the swampy southern edge of Fourth Ward to settle Freedmen’s Town. Paving the streets with handmade bricks they laid in accordance with West African traditions, they built one of the strongest Black communities in the South. Named one of the UNESCO Sites of Memory in 2019, it is the only extant district of its kind — serving as a poignant reminder of the promise of Reconstruction.

Although Houston abolished the ward system at the turn of the 20th century, the neighbourhoods have continued to bear their names, standing in tribute to the resilience of Black America. Over time their fates have reflected the larger political and economic shifts that occurred in Black communities nationwide. In the decades leading up to World War II, the Fourth Ward flourished until “urban renewal” programs brought progress to a halt.

In an effort to turn the tide, President Lyndon B. Johnson launched the Great Society and War on Poverty in 1964, the most expansive social welfare legislation since the New Deal. Among the many initiatives was the Model Cities Program (1966-1974), a series of five-year programs in more than 150 cities nationwide to address complex roots of urban poverty through a multi-layered approach.

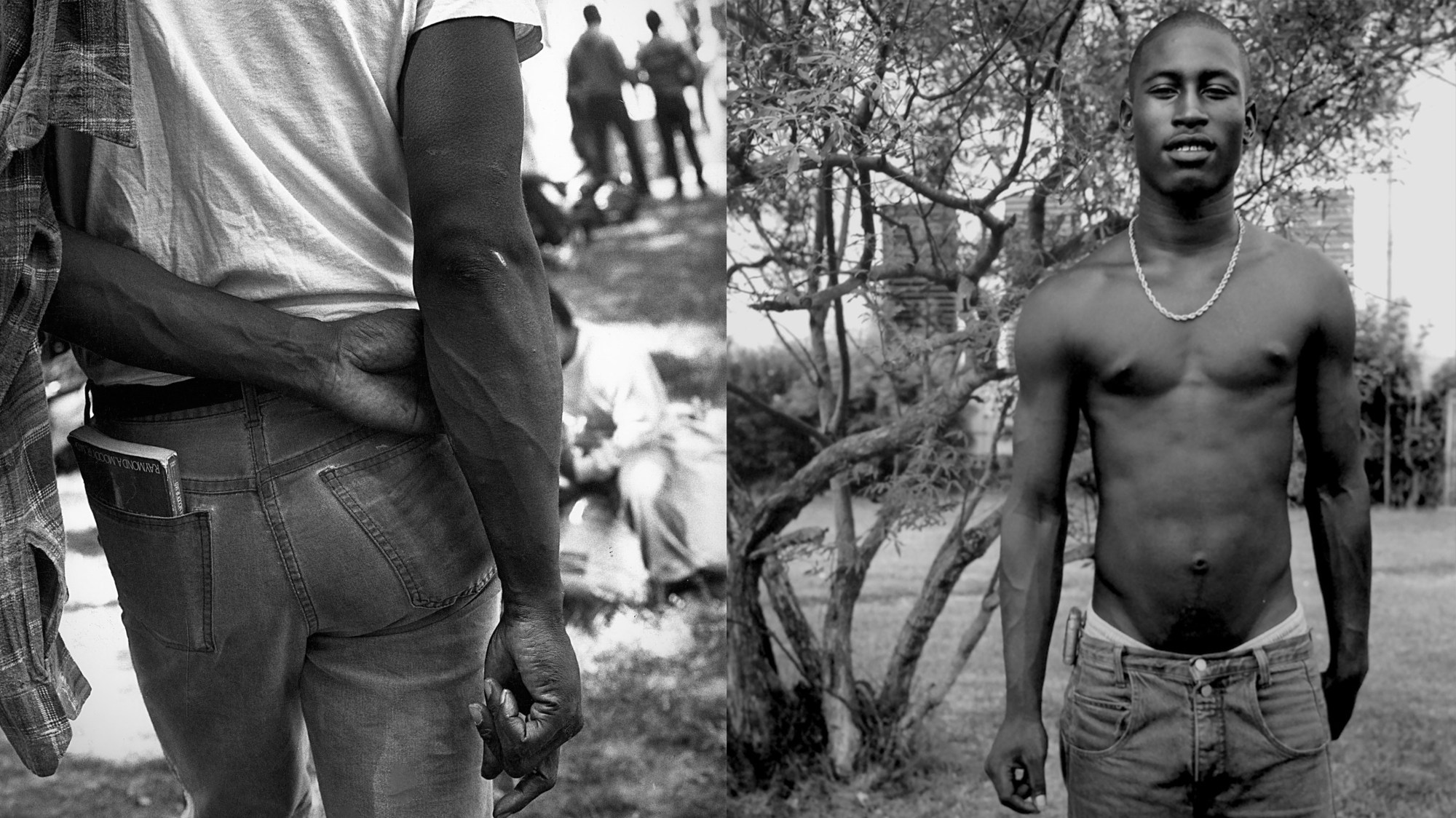

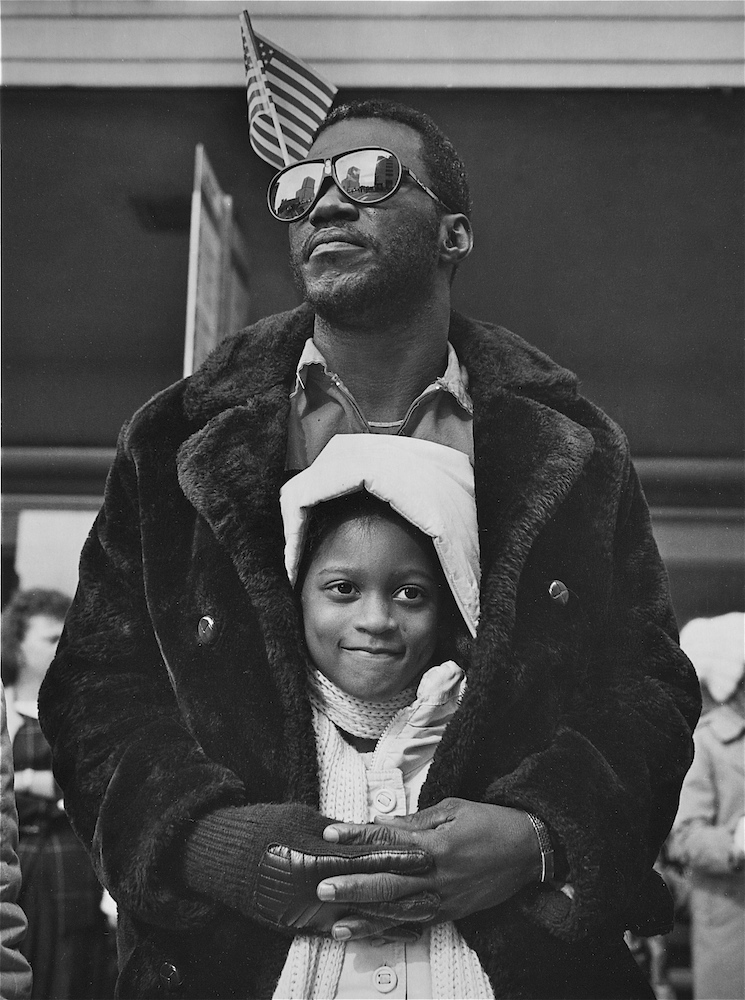

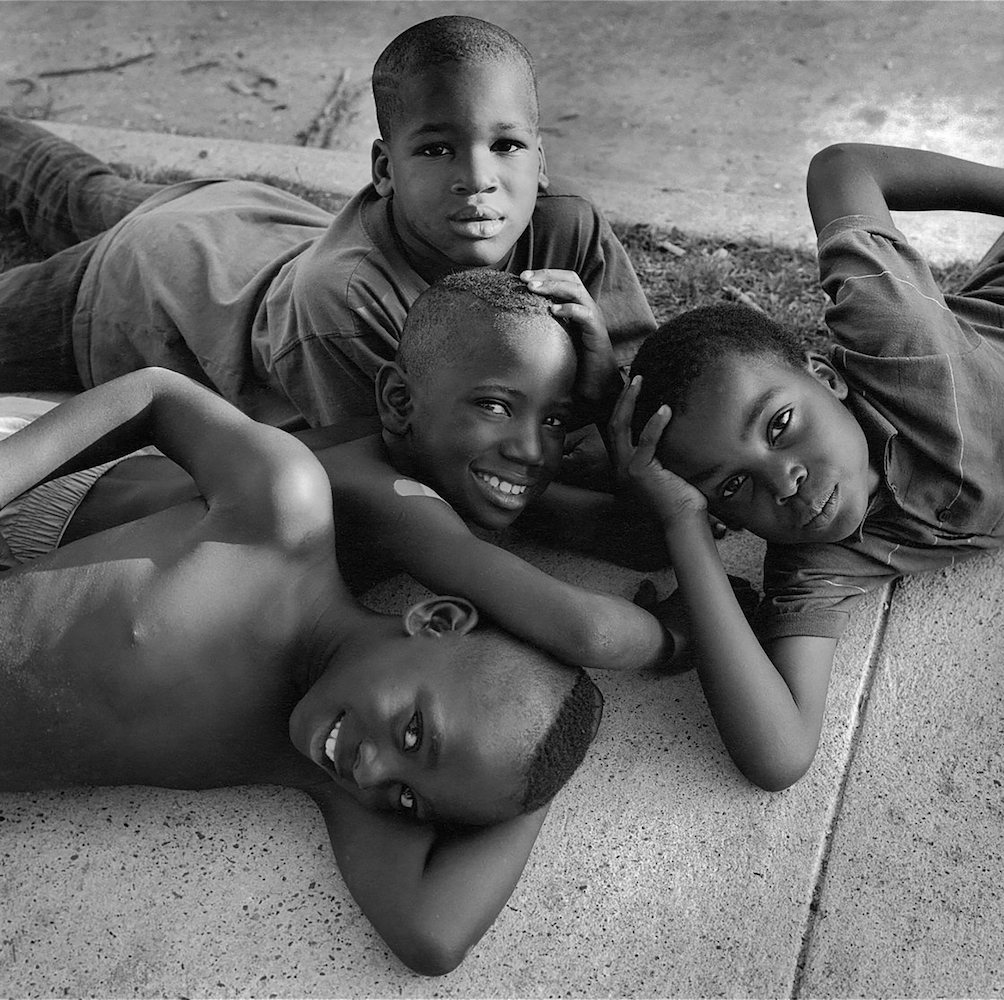

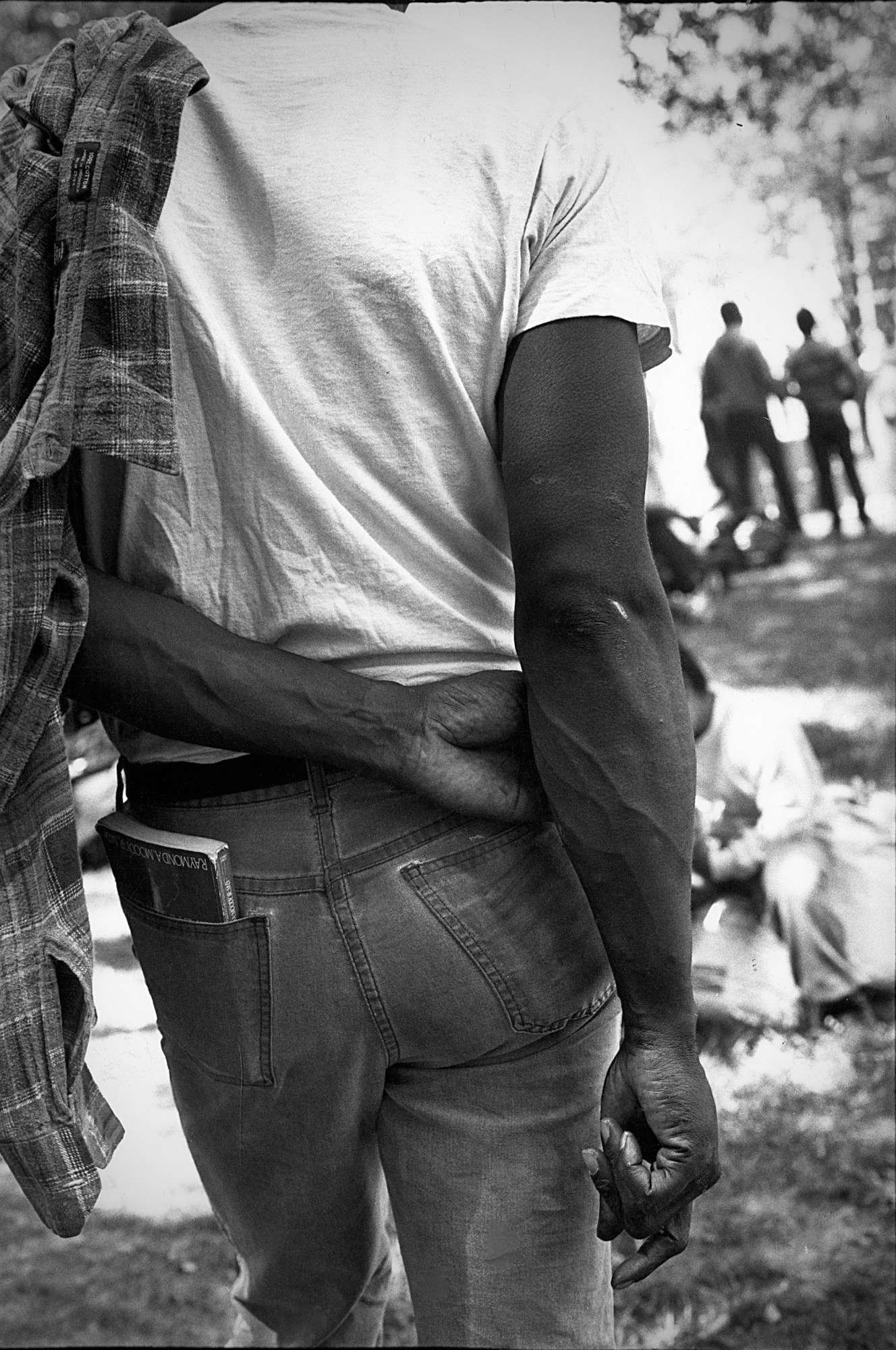

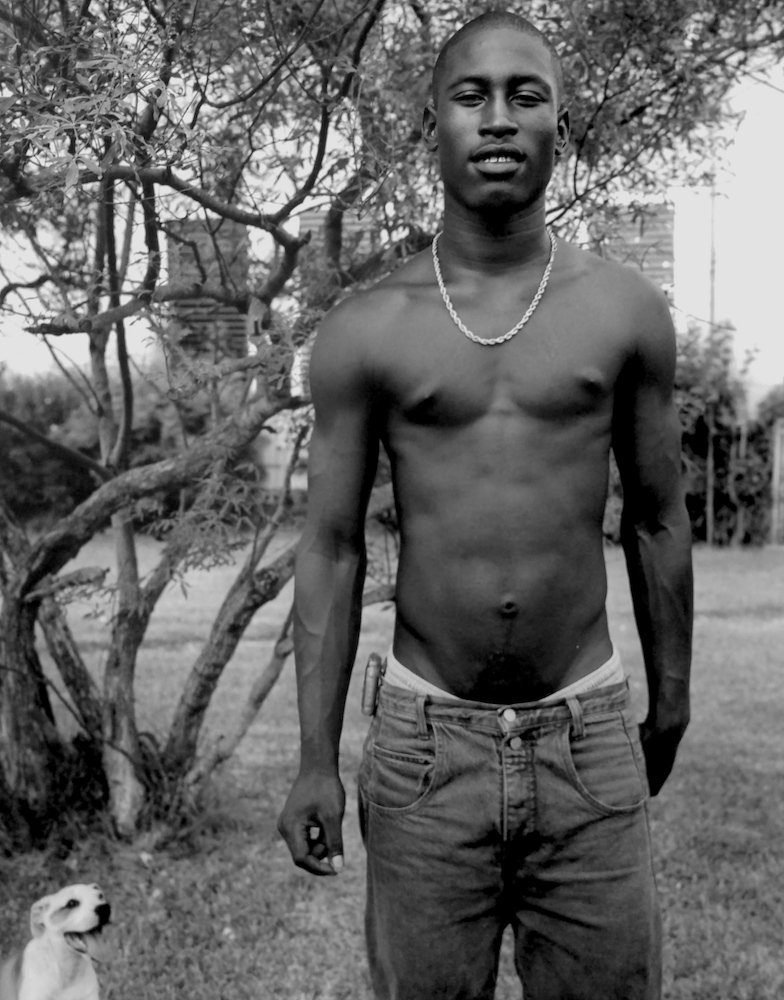

Photographer Earlie Hudnall Jr. first arrived in the Fourth Ward in 1970 as part of the Model Cities Program while studying art at Texas Southern University (TSU) in Houston. The community brought to mind the world he knew best: his hometown of Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Although the cities were 700km apart, Earlie felt immediately at home. “It was a kindred kind of connection,” he remembers. “It reminded me of the people and places that I grew up around: the clapboard houses, the kids playing in the street, people sitting on their porches in the evening, hearing the music and the clatter of people laughing — the universality of the human spirit is what I found.”

As he photographed the people of the Third and Fourth Wards, Earlie followed the wisdom of his professor Dr. John Biggers, who observed, “Art is life. One must draw upon his personal experiences, family, community, and what we’re all about.”

“That stuck with me,” says Earlie, who developed a powerful sense of family, community, and history from his paternal grandmother Bonnie Jean. She organised and preserved photo albums chronicling local residents and relatives, newspaper clips, and obituaries, providing her grandson with a deeper understanding of the world into which he was born.

“There were two articles that really stood out to me: ‘Negro Navy Flyer Shot Down in Korea’ — that was Jesse L. Brown, the first African-American Navy flyer from Hattiesburg. Then there was another article, ‘A Mob Pulls a Man from Jail and Lynches Him.’ It was a Black man pulled in Poplarville, Mississippi, in 1959. Those two articles and my father’s photos made me realise at an early age the importance of documenting one’s community, as well as being aware of what was going on in our communities,” says Earlie, who was just 10 when his parents told him about the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1956. “That was the start.”

Following in the footsteps of his father, who was an amateur photographer in his own right, Earlie joined the Marine Corps and brought a small camera with him to Vietnam. “I was not a photographer, but I was intense about it,” he says. “It came so natural to me. Not that I shot a lot, but I shot at specific times as best I could.”

After completing his tour of duty, Earlie wanted to reenlist, but his mother nixed the idea, so he applied to the art program at TSU, a public HBCU in Houston. Earlie “hopped the ‘Hound” and rode across the American South. He arrived in Texas at age 22, wholly unaware that he would be calling Houston home for the next six decades.

Although he did not set off to become a photographer, he began to hone his talents through study and practice. One day in 1970, Dr. Thomas Freeman, Associate Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, approached Earlie with a unique opportunity. Dr. Freeman, who was also the Director of the Model Cities Program, needed a photographer to document the people of Houston on Tuesday and Thursday evenings. Earlie was game and immediately felt at home in the close-knit communities of the Third and Fourth Wards.

“Despite what people say and about the ‘inner city’, in the Third and Fourth Ward, you have that kind of commonality among people, and I find that to be so inviting and refreshing,” Earlie says. “These are the things I love to photograph. Wherever I go, whether it’s here in the States, Europe, or the Caribbean, I try to get off the beaten path and understand my fellow man. That is important to me as an individual and a photographer because I want the pictures to be truthful, accurate, and have impact.”

Over the next half-century, Earlie would do just this. Devoting his life to documenting Houston’s legendary Black community, he has created one of the greatest photographic archives of a people and a place. Now selections from his archive — which inspired no less than Barry Jenkins when filming Moonlight — are on view in Earlie Hudnall, Jr. at PDNB Gallery in Dallas.

Unlike many photographers, Earlie makes his own prints and takes great pride in the power of working with his hands. “There is something very spiritual and magical when your hands, your eye, and your feelings are [aligned], and people recognise something about the creativity that came out,” he says. Recognising moments of wonder are continuously unfolding before our eyes, Earlie feels an obligation to react and respond, recording these fleeting scenes before they disappear, never to return, and share them with the world. “You can find beauty if you take the time to look at your surroundings: how people survive, how they move, the things they do, the rhythm of their smile, the movement of their spirit, all of this,” he says. “I enjoy watching the metamorphosis of how the community changes. Here gentrification is going on. Some things have been removed and replaced, but that’s how life is.”

Earlie recognises that photography can strengthen bonds across communities as well as help strengthen the memories we hold dear. “As an artist, I should be able to record it so that people can look back and say ‘I remember when…’” he says. “It all goes back to my grandmother, and the way she would tell a story sitting on the porch during the summertime. You had to use your imagination to interpret what she was saying, and it was almost like you had been in a trance. She was telling a story about how things were, and you’d look at your surroundings and the community and you began to collaborate in the mind and pull things together.”

Inheriting the mantle of community historian from Miss Bonnie Jean, Earlie continues forth, connecting the past to the present to help shape our future. “When I travel now, I see remnants of rural outlines of the cities, the customs people have brought with them, the way they do things, the words they use, and how they communicate,” he says. “That is the beauty of being out and having to interact. People become themselves.”

‘Earlie Hudnall, Jr.‘ is on view through 11 February 2023, at PDNB Gallery in Dallas, Texas.

Credits

All images © Earlie Hudnall, Jr. Courtesy PDNB Gallery, Dallas, TX