Toffs and posh twats have provided some lofty screen entertainment in recent years — with Succession, The White Lotus and Triangle of Sadness among the arch-culprits of our strange obsession with the lives of the wealthy elites. But as Britain endures a seemingly endless Tory winter — marked by widespread labour strikes, profound economic disparity and cost-of-living crises — the plight of the working-class hits ever harder. The BFI’s latest film season, then, couldn’t be more timely.

‘Acting Hard’ zones in on the theme of working-class masculinity, exploring 13 major works and cult classics from celebrated directors like Ken Loach (Kes), Jonathan Glazer (Under the Skin) and Shane Meadows (This is England). In films that span Thatcherite Britain to the present, stars such as Daniel Day-Lewis, Paddy Considine, Ashley Walters and Danny Dyer lead stories of brutal vigilantes in the Peak District, Chelsea football hooligans on the rampage, a former felon returning to a Hackney housing estate, and ‘neds’ searching for paradise in Scotland.

Race relations and queer identities provide additional thematic backdrops, as complex tales of violence, repression and injustice invite viewers to consider a spate of misunderstood characters and the societies that create them.

My Beautiful Laundrette (Stephen Frears, 1985)

In Thatcherite South London, fresh-faced British-Pakistani Omar (Gordon Warnecke) cares for his sick father — a former left-wing journalist who drinks Smirnoff for breakfast. Elsewhere, Johnny (Daniel Day-Lewis) is a bleach-haired Millwall supporter who roams the streets with a racist gang. After a chance encounter, an unlikely partnership — and a romantic relationship — is formed as the two young men agree to fix up a local laundrette.

What’s remarkable about My Beautiful Laundrette — originally shot for Channel 4, but distributed in cinemas after receiving rave reviews at Edinburgh Film Festival — is how non-judgementally it treats queerness at a time when it would have been a controversial storyline. Indeed, Omar and Johnny get on “like daal and chapatti” — but it’s the clashes between classes and nationalities that provide the more urgent moral concern of the film, which received both an Oscar and a BAFTA nomination for Hanif Kureishi’s script.

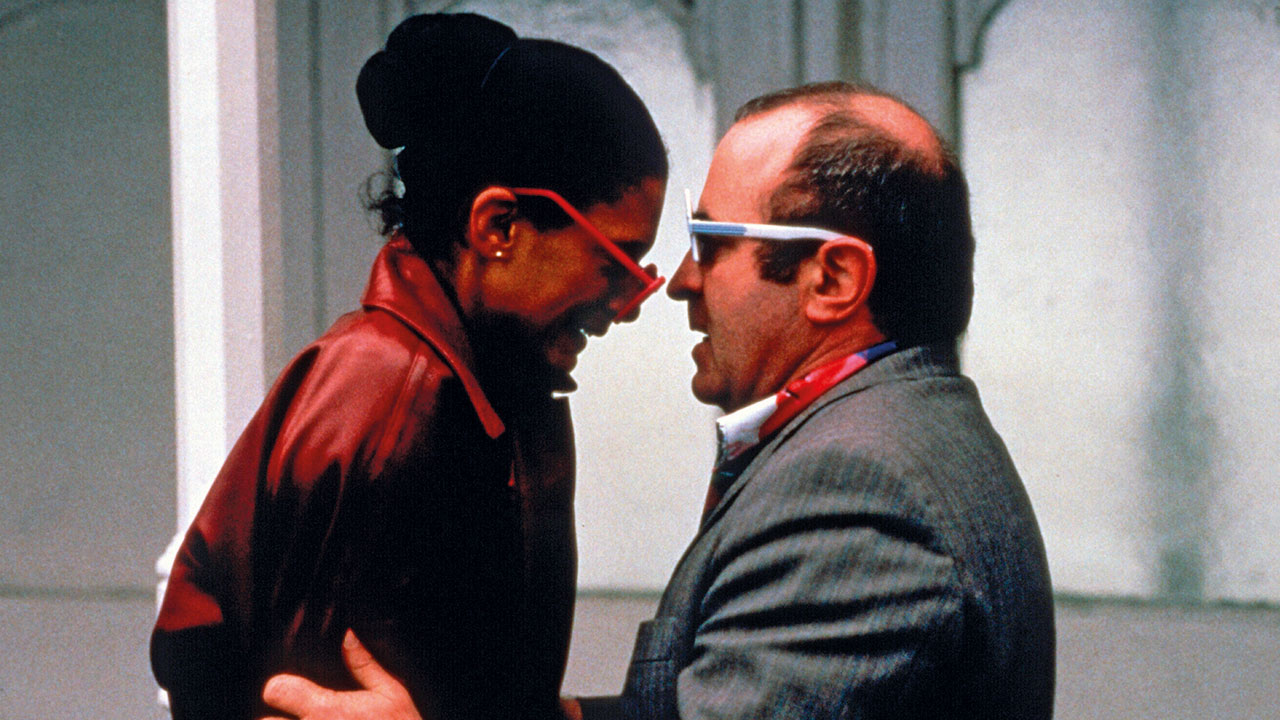

Mona Lisa (Neil Jordan, 1986)

A few years after lighting up the screen as a menacing cockney gang leader in The Long Good Friday (John Mackenzie, 1980), Bob Hoskins returned to London’s underworld for what would arguably be his most essential film role. Criminally under-seen today, Mona Lisa remains a masterpiece of British noir cinema — thanks in part to the powerhouse performance of its lead, who won a BAFTA, a Golden Globe, a Cannes Best Actor prize, and an Academy Award nomination for his work.

Hoskins plays George, a low-level gangster to slimy kingpin Mortwell (Michael Caine), who works as a driver for high-class escort Simone (Cathy Tyson, also nominated for a BAFTA and a Golden Globe) after returning from a seven-year prison sentence. Despite their differences, the two form a close bond — which leads George to look into the disappearance of Simone’s friend, who may have fallen victim to a violent pimp. As his investigation deepens, a series of shocking truths are revealed — leading to a fatal confrontation at Brighton’s recently-demolished Royal Albion Hotel.

Sweet Sixteen (Ken Loach, 2002)

No exploration of working-class Britain on film would be complete without an eye on Ken Loach — arguably the most influential social critic filmmaker of his generation. Arriving 33 years after Kes (1969), and 14 years prior to his second Cannes Palme d’Or win with I, Daniel Blake (2014), the director journeyed into the desolate estates of Inverclyde in Scotland to tell the story of teenage ‘ned’ Liam (non-actor Martin Compston, who won Most Promising Newcomer at the British Independent Film Awards for his performance) embroiled in a life of petty crime as he awaits his mother’s return from prison.

Featuring a profanity-laced dialect so thick that the film had to be distributed with subtitles in some territories, and a visual palette so grey that it seems to drain the colour from the screen, Sweet Sixteen offers a bleak examination of a world in which a mobile home “with a telly and a microwave” is likened to a paradise. But beneath this cold and washed-out exterior is warmth, humour, and a heart that beats powerfully — the anchor to a desperate, devastating climax.

Dead Man’s Shoes (Shane Meadows, 2004)

Shot in three weeks on a budget of just £723,000, Dead Man’s Shoes was the final Shane Meadows feature before his mainstream breakthrough with This is England in 2006 — and it remains an unnerving watch today.

Inspired by the impact of bullying and drug abuse on a friend of the director’s from his hometown of Uttoxeter, the film tells the story of a vengeful ex-paratrooper (Paddy Considine, also co-writer) who terrorises a lowly drug gang in the Peak District as payback for the torment they inflicted upon his disabled brother (Toby Kebbell). With a cold realism supplied by improvised dialogue and intrusive, handheld camerawork, the film manages to be both acutely terrifying and darkly comical as small-town hard-men break down in the face of the wrath of a brutal vigilante.

The film returned a record eight British Independent Film Awards nominations upon release — as well as a single nod at the BAFTAs. Two decades on, director Meadows will revisit what remains his grittiest film via an in-person Q&A at the BFI’s screening on 12 September.

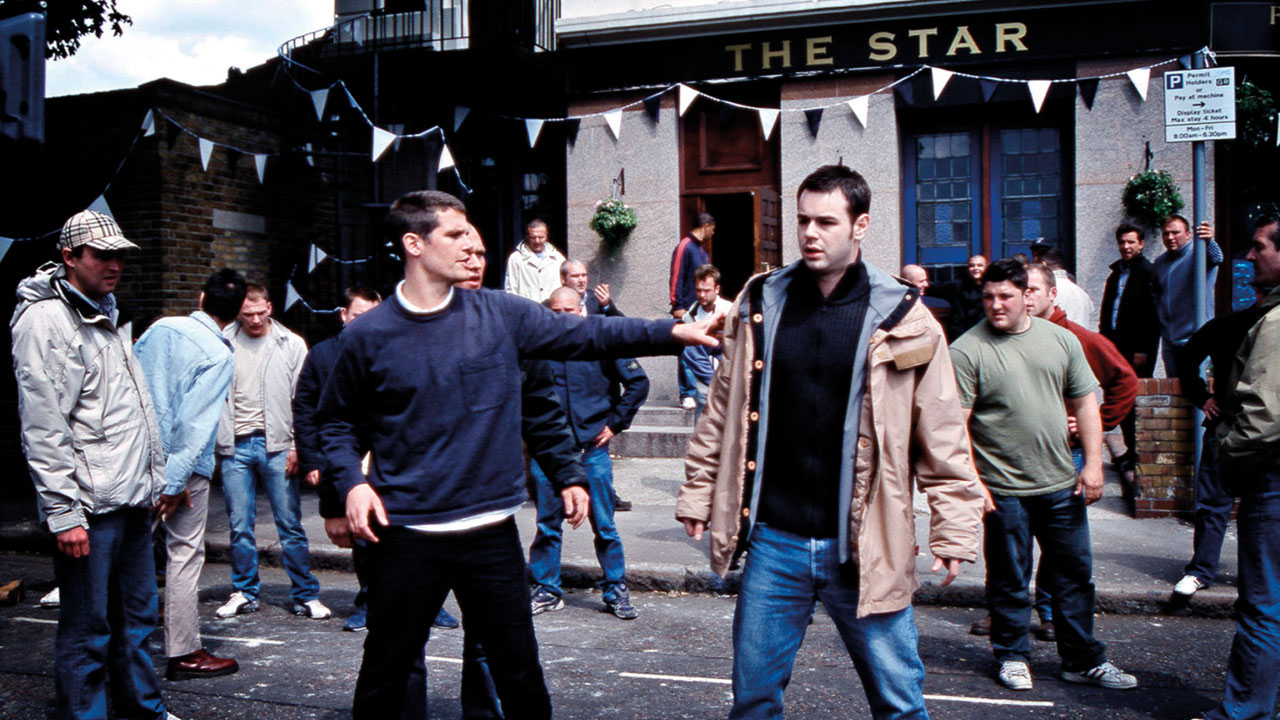

The Football Factory (Nick Love, 2004)

Once the subject of endless playground quoting, cockney cult film The Football Factory today offers much more than a barrage of pints, profanity and passionate football casuals out for a scrap. It’s also a travelogue of the everyman’s early 00s London, taking in sights like Piccadilly Circus, Seven Sisters Tube station and Millwall football stadium to the sounds of The Libertines’ “What a Waster” and The Streets’ “Fit But You Know It”.

Throw in prime Danny Dyer — who, as Chelsea FC hooligan Tommy Johnson loves nothing more than “casual sex, watered-down lager, heavily cut drugs, and occasionally kicking fuck out of someone” — plus an audacious editing style that mixes flashbacks, freeze-frames and hallucinatory dream sequences, and you’ve got a striking exploration of a violent and largely undocumented subculture that was rife in Britain at the turn of the century. Dyer will introduce the film in person following an exclusive ‘In Conversation’ event on 25 September.

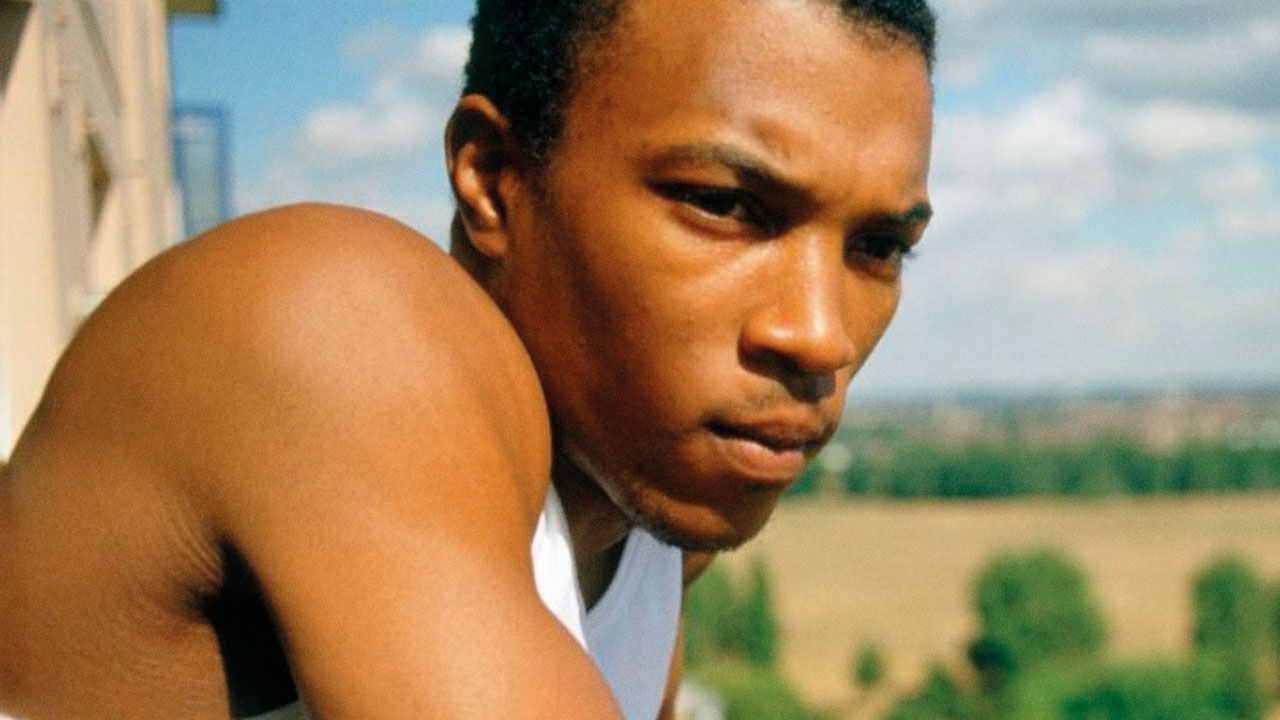

Bullet Boy (Saul Dibb, 2004)

So Solid Crew’s Ashley Walters won Best Newcomer at the British Independent Film Awards in 2004 for his role as Ricky in Bullet Boy, in which he portrays a young man returning to his Hackney council estate after serving time in jail. He’s eager to leave the past behind him, but it doesn’t take long for erratic friends like Wisdom (Leon Black) to push him back towards a life of violence and intimidation, leaving the audience to wonder how younger brother Curtis (Luke Fraser) will be affected.

Close-quarters cameras, on-location shooting, and a barrage of sharp London street slang all serve to enrich Saul Dibb’s 2004 feature debut with a bleak realism. But it’s also an emotionally arresting film, propped up by some outstanding dialogue delivered by a cast of captivating performers. From today’s perspective, the film almost feels like a precursor to another Ashley Walters-led drama set in the ends: Channel 4 and Netflix production Top Boy.

‘Acting Hard’ is screening at the BFI Southbank and online via the BFI Player from 2 September.