There’s so much that has already been said and written about Paris that it’s difficult not to project our own ideas onto it. It’s almost too easy to visualise the city through whichever lens we choose to magnify it, convincing ourselves that the image of Paris that we’ve conjured up in our heads mirrors what it’s really like in real life. We might imagine it as lived by the bohemians and flâneurs of the early 20th century, who sat drinking coffee for hours on end at cafés in Montmartre. We may see it through the lens of the fashion world, its star-studded models walking on runways with the Eiffel Tower as a backdrop. Or we might even consider Paris through its charged revolutionary history, one that could spark a fire inside of us.

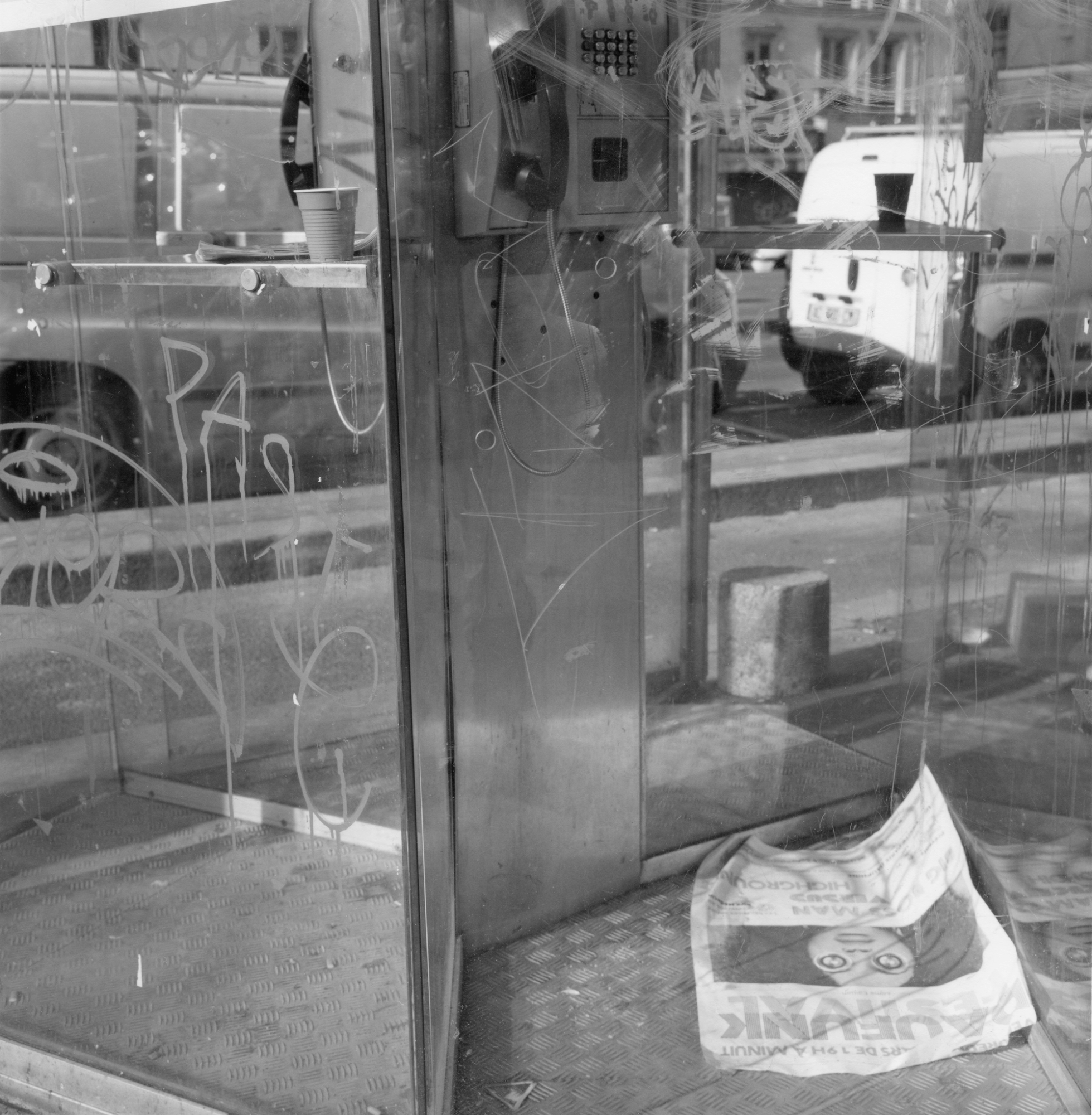

For French photographer Thomas Boivin, “the risk was there, of falling into a cliché” while documenting Paris. Thomas started photographing the city in 2010 after moving to Ménilmontant. He began documenting the everyday as lived by the residents of the northeastern neighbourhoods of Paris, focusing on his own and on neighbouring Belleville.

Part of the 20th and last arrondissement of Paris, both Belleville and Ménilmontant are two historically working-class areas with a rich countercultural history. They saw the birth of many key figures of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as Jane Avril and Édith Piaf, born in Belleville, and Maurice Chevalier, born in Ménilmontant. “Ménilmontant has been overshadowed by Montmartre, but it was bohemian, too,” Thomas says.

Thomas took hundreds of photographs of shopfronts, portraits of strangers, and stills of parks, recording Belleville and Ménilmontant throughout the 2010s. 34 of these images would end up being featured in his 2022 photobook, Belleville, a document of contemporary daily life in the French capital that portrays the multicultural identity of the northeast and its people.

Among the street photographs featured in Belleville, Thomas recently rediscovered a set of pictures — approximately 40 — that he took during the 2010s in more spontaneous and unadulterated settings.

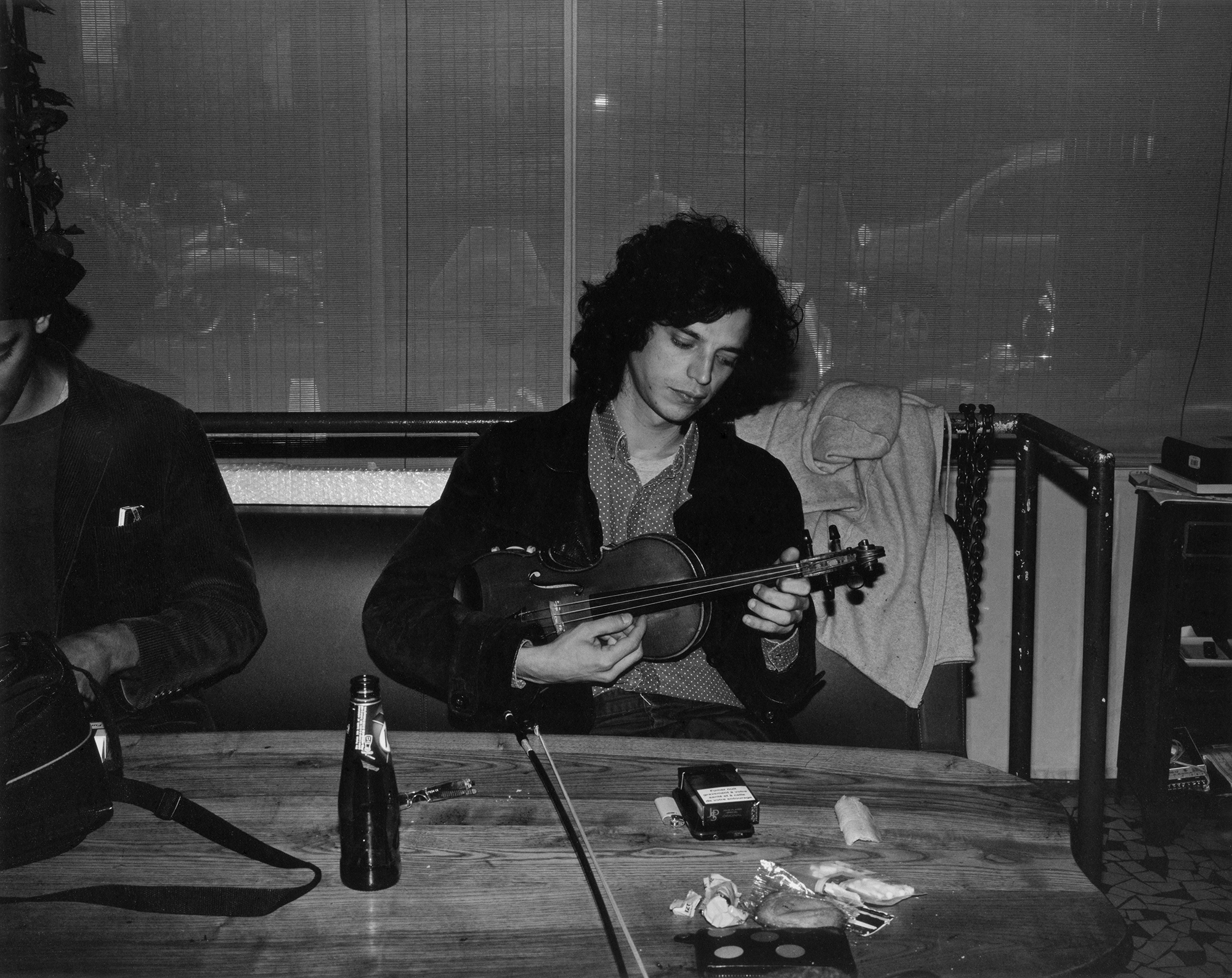

He captures still shots of hours spent at cafés, fleeting details of his former apartment, and quick portraits of the people he used to meet during those years. 32 of these 40 photographs are featured in his new photo novella, Ménilmontant. “I took these pictures without thinking about them,” he recalls. “It’s interesting to see that they feel distinctly Parisian.”

In one still life, we see a row of empty wine bottles, used napkins and plates on a table — evidence of what might have been a dinner among friends. Through the absence of wine, food, and people, Thomas captures the echoes of laughter and lively conversations that might have preceded the photograph being taken. In another photograph, he takes a quick portrait of a woman sitting in front of him while she lights a cigarette. “As much as Belleville was about trying to meet with strangers, Ménilmontant is much closer to the people I would meet as friends,” Thomas says.

For Thomas, Ménilmontant becomes a practice of rediscovery, a reminder of the places he would regularly visit and the people he would often meet. For us, Ménilmontant provides a glimpse of a Parisian’s day-to-day, unobtrusive images that capture an insider’s view of what living in contemporary Paris may really be like.

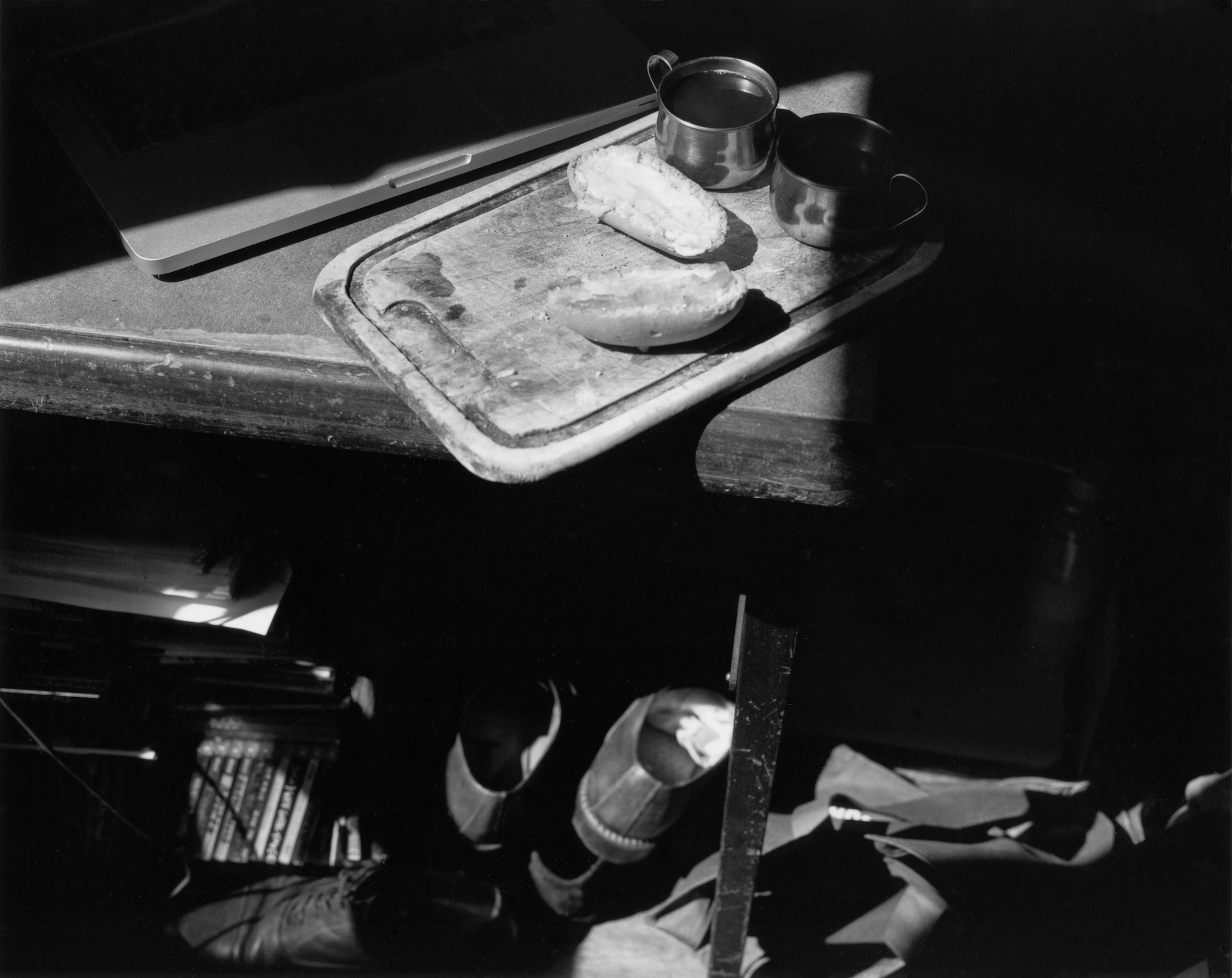

When Thomas wasn’t walking and photographing the streets of his neighbourhood, he would spend many hours sitting in cafés. “When you are tired of walking around, the easiest way to get a little bit of rest and not pay too much is a coffee,” he says. “I would have this habit of buying the cheapest coffee in one of the few places where coffee was cheap three or four times a day.” In Ménilmontant, we catch glimpses of the “in-between moments” when he wasn’t taking photographs of the streets or working at night — a table with an empty coffee cup and a glass of water; a couple chatting, one of them with a coffee in one hand, the other smoking a cigarette; a newspaper in Mandarin left open on a table; the inside of a café with chairs neatly tucked under tables.

“When I go out on the street with the camera, I have the intention to take a portrait. With Ménilmontant, I would have my camera and would be having a coffee, and suddenly, the light would be nice so I would take a portrait.”

Unintentionally and almost subconsciously, Thomas records his own fleeting memories of Paris, capturing the simple in-between moments of everyday life through each individual photograph. “Most of these pictures are pictures that I wasn’t looking for,” Thomas says. Yet, by placing them together in the novella that is Ménilmontant, he evokes a specific narrative of Paris that reminds us of the artists and bohemians who lived it during the 60s. “I lived a Parisian life in the sense of the bohemians, but I lived it in today’s Paris,” Thomas says. Through Ménilmontant, we see how one of the many narratives of Paris seeps into his own present.

‘Ménilmontant’ is published by Stanley/Barker and is available to buy here.

Credits

Images courtesy of Thomas Boivin and Stanley/Barker