“It doesn’t burn, it doesn’t break, and you can kick it,” multi-disciplinarian Greek artist Andreas Angelidakis says of his installation “Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity.”

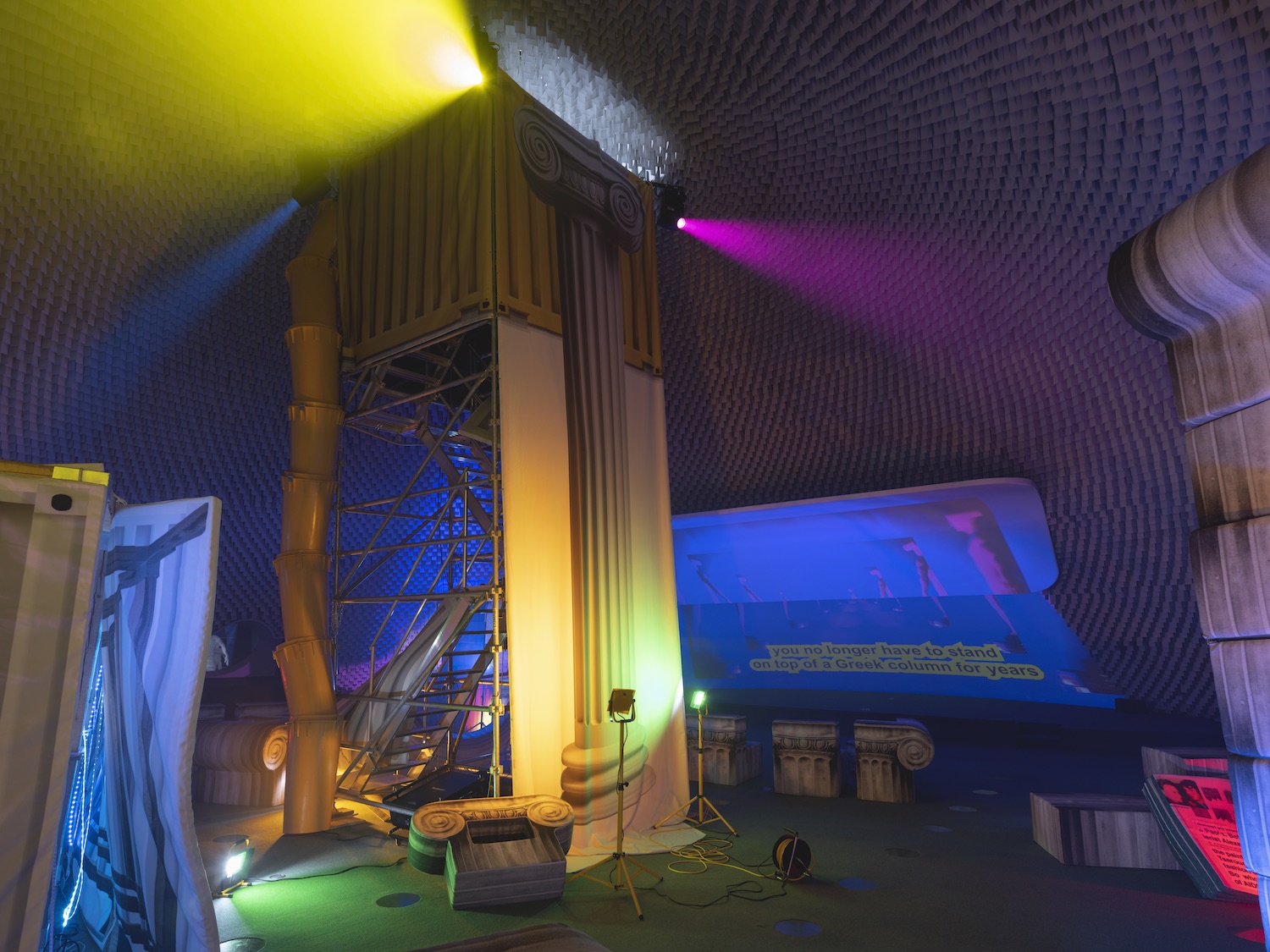

Exploring classically structured frameworks and the mutable nature of human mythologies, his imagined excavation site mixes totems from antiquity with contemporary queer culture. The immersive space — on view in Paris until October 30th — transforms the interior of the 60s-built Espace Niemeyer, a Communist Party HQ designed by iconic Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer. Andreas, who pivoted his training as an architect into a conceptual practice, created soft sculptures and videos that reference old ruins, monumental heritage, anarchic ‘zines, internet culture, 80s-era gay icons, cruising spots and popular tourism. The installation is as fun as it is complex: its layers offer different access points, be they alternative history, contemporary art, design folly, or queer chronicle. The work was commissioned — carte blanche, with no theme — by Audemars Piguet Contemporary, which works biannually with artists from inception to exhibition.

We spoke with Andreas in Paris amidst the installation about being a Google archaeologist, reframing history, and the grandeur of creating a “lockdown Xanadu.”

So: tell me about the Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity. Sounds highbrow!

I made a fictional organization that brings together my interests. Mostly archaeology, because I’m always fascinated by finding and reconstructing. The installation is a kind of mock-up excavation site. There are pieces based on the American School of Classical Studies: the original publication is a booklet, starting from the 60s until now. I wanted to insert personal stories over their texts. I blurred the background content because actually the School didn’t want this used like that, even though I sent them a proper proposal. I was like, Whatever, sue me. (…I didn’t say that.)

Tell me about conceptualizing the installation specifically for this pretty bonkers Modernist Communist space.

This space fits the project perfectly. The installation consists of many pieces, and the venue basically became part of the conversation. It creates a vortex of references. [Oscar] Niemeyer’s future was something that was never fully realized: our public offices don’t look like this. What I’m doing is inserting these para-histories, or other histories, around antiquity that are not official. It’s re-excavating the past, in a future that didn’t come to fruition.

I started thinking of this environment during lockdown… I stayed forever by myself trying meditation apps and jogging and drinking and antidepressants and everything. I even had a nickname for it: lockdown Xanadu.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

The oversized soft sculptures are so much fun.

All the pieces actually make a modular set. I call them “soft ruins.” It’s a canvas fabric, with specifications for museums. You can sit on them.

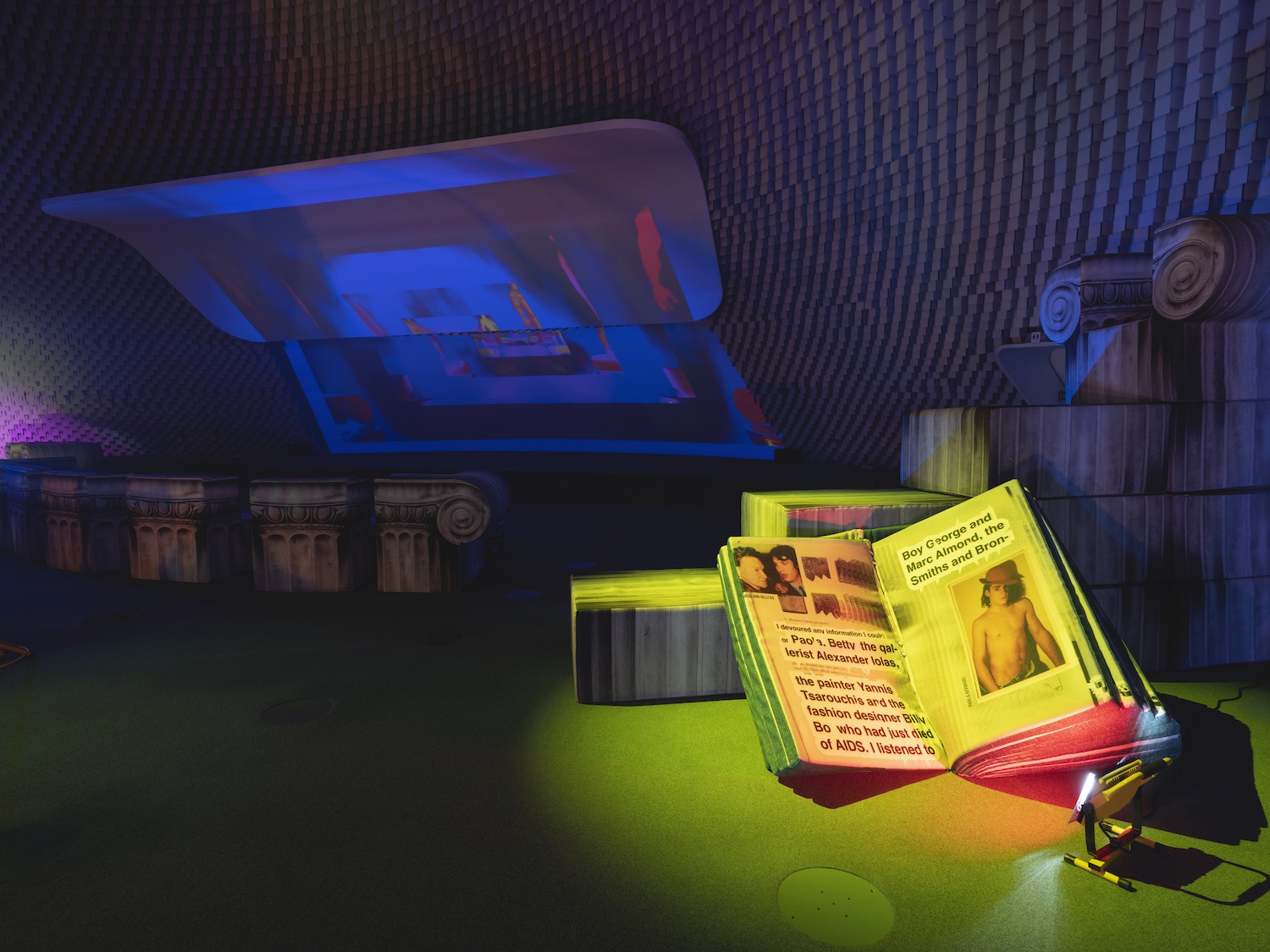

And the oversized soft booklets too.

You can use them as a loveseat for two people; the volume is very simple. They’re soft, literally, but also from software. I used to work a lot on online communities: social video games, like Second Life and before that Activeworlds. On those platforms, they use texture mapping. I added a digital touch, so it looks a bit like a computer rendering.

The installation is meant to be immersive and interactive — people are allowed to touch these and move them around. They’re quite lightweight. This one is called “On Being High,” which is about the Stylite monk being high on the column… and then us being comparatively high on everything from, you know, running to yoga to coffee to drugs. This one is called “Future Memory Club,” about the use of the ‘antiquity aesthetic’ in gay nightclubs, gay saunas, and gay civilization. There’s many layers: to see everything, you’d have to read all the booklets. And sit on them as well, of course.

Given how vast the installation is, how do you compose all the pieces? Do you map out ideas, or is it one-thing-leads-to-another?

It’s totally one-thing-leads-to-another. I’m a kind of Google archaeologist. I will start with one thing, and then if it leads me to a totally random other thing, I consider that. This Temple of Zeus, for example, which was meant to be the largest temple in antiquity, was never really wanted in the city. Democracy came along and sort of canceled it, because it was too big. And then Hadrian came along with a bigger ego and finished it.

My process is… I knew the title of the project, and I knew what it was about. But when it came to this space, I was almost more like a curator. I always consider: what’s fun for the visitors? Because suddenly these pieces that people can lift or set over there…. that’s how you get people to be a bit engaged. And people seem to like to hang out here. But you never know, in these spaces that are meant to be social, how the public reacts. Every city is different. In Sweden, for example, nobody touched anything. In Turkey, they would be turning everything upside down. Like: YAY! Party! Which is also a bit of a critique of exhibitions. Or not a critique, but…

It reflects back on behaviors that are expected.

Exactly. That’s what I’m trying to do: to play with how to extract behaviors. It’s Minecraft behavior. Like, Oh, I can move this big block here and put it there.

That word — play — I think is too often missing from art. But here, art’s distancing is replaced by tactility and mobility and accessibility.

Yes. I use the word play a lot, because a lot of this process of archaeology was also me excavating myself. One usually excavates their childhood, because that’s the sort of magical part that’s far away. Antiquity is the same, but for our civilization. It is, in a way, the childhood of history: it’s that part where they saw things for the first time; they invented things. But we’re in a moment where… it looks like we fucked up!

The notion of play is also related to — after all these years of therapy, and switching types of therapy, and supplements and everything — regaining that freshness you had as a kid, where you were discovering things before all the conditioning. You can’t tell people to play: it has to happen by itself. I don’t know if people will play in here, because it’s a very sort of “respected” space.

But that’s why it would be all the more thrilling!

I’ve asked the security guards to use the furniture as much as possible, in any way that they want, so that people get a bit encouraged. Because then the party starts.

I remember at Art Basel — before COVID — there was a big piece of mine, and the first day I asked the guards to push it, so it collapsed. By the third day, a 70-year-old collector with his son was pushing things and falling onto them. So… it queers the exhibition format.

Speaking of queering: you’ve also implemented a fun and campy discotheque aspect. Can you elaborate on that?

Yes: it relates to the use of antiquity in nightclubs. Especially gay bars, in the 80s: all the Greek columns. It’s because the Greeks invented gayness! In one of the books, I go into that: that basically the Greeks invented the daddy typology. All these philosophers had, like, a young lover to whom they taught things. As a mid-50s homosexual, I can see the daddy threads prevalent today. You’re supposed to buy the younger ones tickets!

There’s a video about ‘the algorithm.’ Can you tell us about that?

The video’s a progression of a Stylite monk, and the narrative is about how algorithms become a mirror for ourselves. We get fed what we already like, so we sort of see ourselves in what the algorithm feeds us. The algorithm has become so prevalent that now you download an app, and it already knows what you like. Because it knows from every browser, every other thing.

That creepiness aside, you have lots of other things going in the exhibition too. A smoke machine. Music.

Sorry for the smoke—the Stylite likes to get high.

The track playing is “I Feel Love” by Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder — very classic gay 70s disco, very hedonistic. Basically, she’s having sex. And Klaus Nomi redid it, changing the lyrics in his opera voice. He was dying of AIDS. What do you want? Where do you go? Sorrow, despair, please let me go. He turned this sex track into a funeral track. The Klaus Nomi type of queering is very difficult to pin down. I was a huge fan when I was a teenager. It was the first artist I heard of dying of AIDS, as a kid in suburbia, trying to figure out what it is to be gay.

The exhibition will eventually travel. Do you have your sights on particular places?

I don’t know if anything can top this. The Colosseum, maybe.

Credits

All images courtesy the artist.