From the mid-century onwards, thousands of skilled clothesmakers left the Caribbean for the UK in pursuit of more lucrative professional opportunities and, consequently, better lives. But, in an egregious plot twist, it soon became clear that their qualifications as tailors or seamstresses meant little in a job market controlled by the colour bar – not least a country where racist violence and discrimination were a daily norm. This history, sadly, is not one consigned to discussions in the past tense. While the barriers that young Black designers face today may not be quite as explicitly enforced, they nonetheless persist, just in different guises.

As such, telling the story of Black British fashion, then and now, is no small feat, requiring both a nuanced reappraisal of the tale told so far and a deep dive into the sociopolitical context that has defined Black Britons’ lived experience since HMT Empire Windrush first docked on Britain’s shores. Intent on tackling this very task, the trio behind Black Orientated Legacy Development Agency (BOLD) – creative director Harris Elliott, academic-cum-designer Andrew Ibi and brand consultant and writer Jason Jules – have curated an unflinching exhibition, The Missing Thread at Somerset House. Held across several themed galleries, the show broaches Black British fashion, homing in on the clothing, photography, pop culture, art and fraught backdrop that culminated in the looks and styles presented throughout.

From the outset, it becomes clear this is a politically nuanced – and charged – exhibition. The first room considers the concept of “home”, treating it as a contested space for Black Britons. To enter, visitors must walk through Harris Elliot’s “Fragile House” (2023) installation, a small-roofed structure built entirely of measuring tapes in a palette of yellow, red, green and white. Inside, Pogus Caesar’s action snapshots of burned-out cars and police altercations during the Handsworth Riots of 1985 adjoin Neil Kenlock’s infamous photograph from 1974. The latter, for those unfamiliar, depicts a Black woman gesturing towards graffiti that reads, “Keep Britain white”. As one walks through the space, speakers play a soundtrack spanning Mad Professor’s dub classic, “Kunta Kinte” (1981) and Janet Kay’s lover’s rock anthem, “Silly Games” (1979), in an ode to the cultural cross-pollination among Caribbean-born Brits.

Some would call this “immersive”, but that cheapens what is undoubtedly an astute curatorial approach. Summoning an emotional response as well as cerebral reflection, it aptly prefaces and contextualises the by-any-means optimism that birthed the clothes to follow. “It was essential it didn’t appear like another fashion exhibition,” explains Harris. “What’s missing isn’t that visitors don’t know the designers’ names, but sometimes, the backstory: what they’ve had to do [and] what they’ve had to endure in order to reach the levels they have.”

Of special note is the tailoring on show. Indeed, the exhibition does a stellar job of spotlighting the deft hands of names you might have missed in an otherwise whitewashed fashion and art canon. Bayode Oduwole’s boxy, high-water suits for his label Pokit are mounted in a triptych, screen-printed with primary colours and left with raw seams and unfinished stitching. Nearby, a traditional bus ticket machine is loaded with measuring tape, commenting, again, on the limited availability of jobs Black fashion professionals had access to. Elsewhere, artist Joy Gregory’s sepia print from the “Objects of Beauty” (1992–1995) series depicts a traditional bustier with measuring tape placed below, a jibe on the coiffed and strapped-in beauty ideals imposed on women. For many, it’s a welcome introduction to the artist’s work, widening the scope of clothing-based feminist art beyond Sarah Lucas and co.

This breadth of mediums is a running thread in the show, mirroring the hybridity that diasporic designers have long embraced while jumping through hoops in an industry that has long dismissed them. “The story of Black fashion culture is complicated,” says Andrew Ibi. “It’s not really fashion designed in the way you might see on a runway. It’s more from a subcultural movement that stays in the clubs, invisible to most.” Indeed, in his eyes, fashion was dictated by class, and the colour bar meant many Black Brits were – regardless of skill set – de-facto working class. In this sense, Black British fashion was, in its earliest days, about escape; blowing off steam after a hard week in the Ford factory or busting a gut in public services.

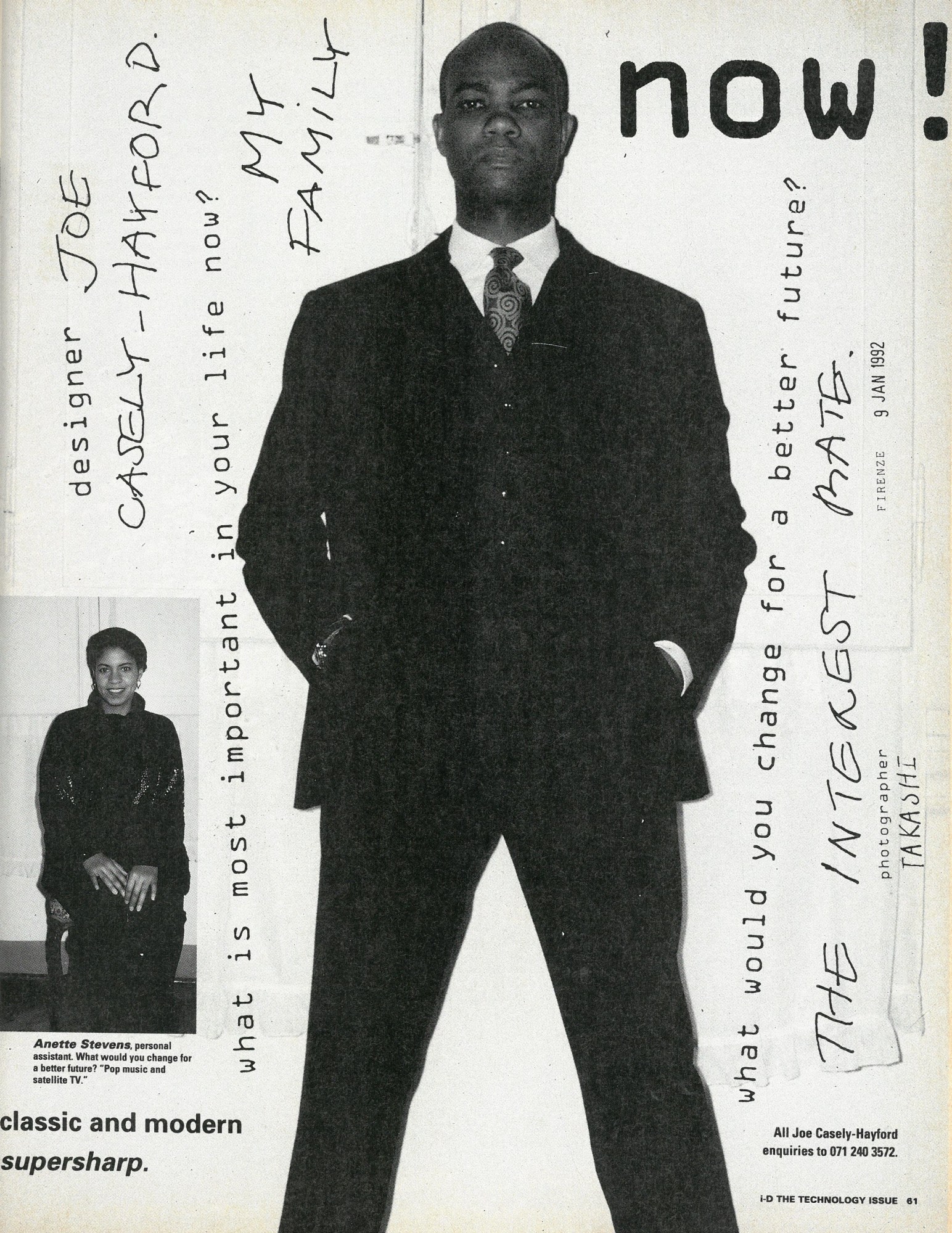

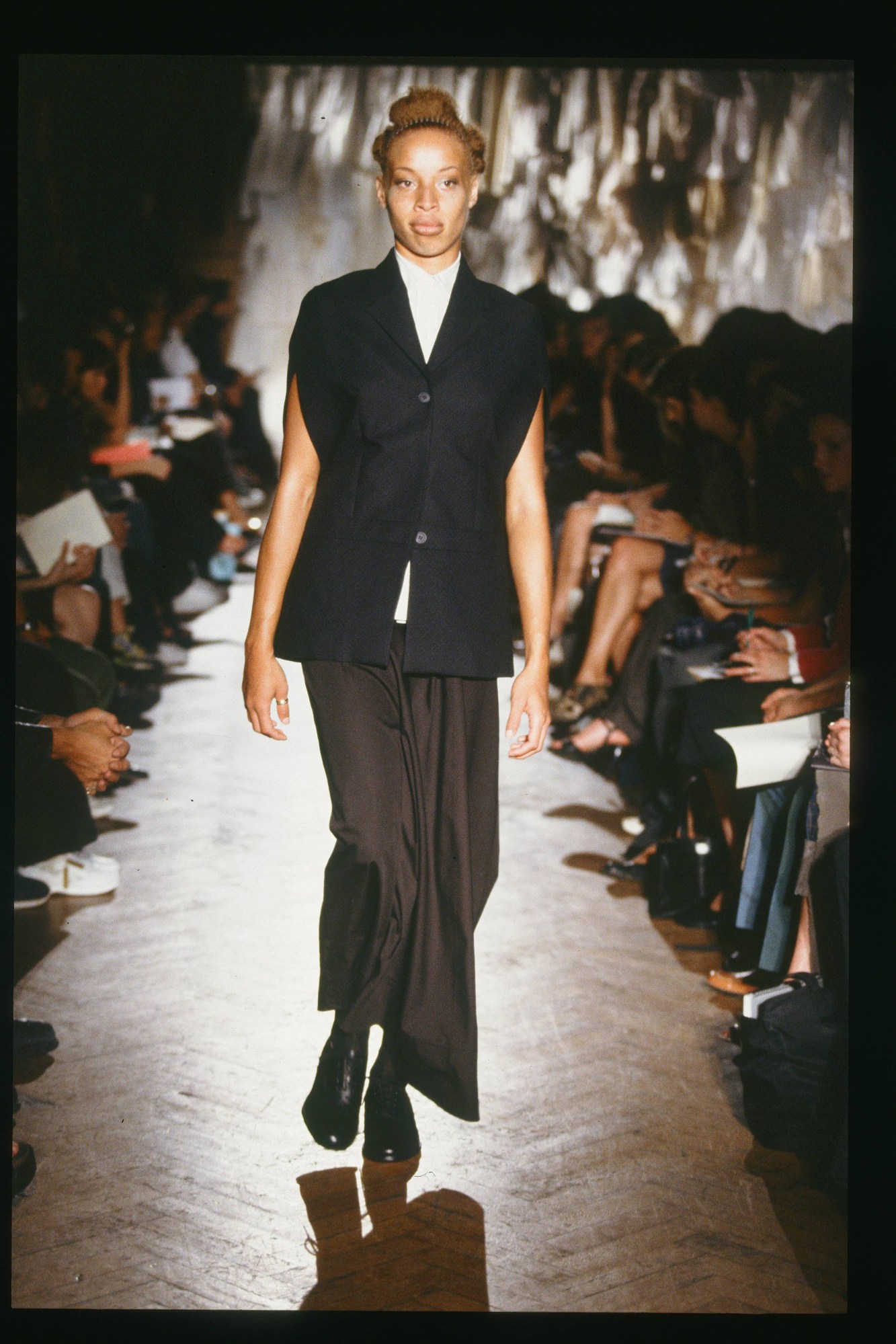

However, as time went on and conditions improved at a snail’s pace, pioneers emerged, willing to grin and bear capital-F fashion. The late designer Joe Casely-Hayford, whose work fills a whole section of the show, is a case in point. Entering into a high-fashion sphere in the 80s, he brought with him a fresh mood board of ideas, looking beyond the well-rehearsed icons of yesteryear, merging the craft of tailoring with a more contextual approach. “In a way, many of the items and influences [in the show] – photographers like Rotimi [Fani-Kayode] or Maud Sulter, Chris Ofili and, of course, music – would have been central to Joe’s process as a designer,” says Andrew. For Joe, it was less about discussing tailoring for tailoring’s sake, but instead, through a lens of cultural protection and aspiration or colonial connotations.

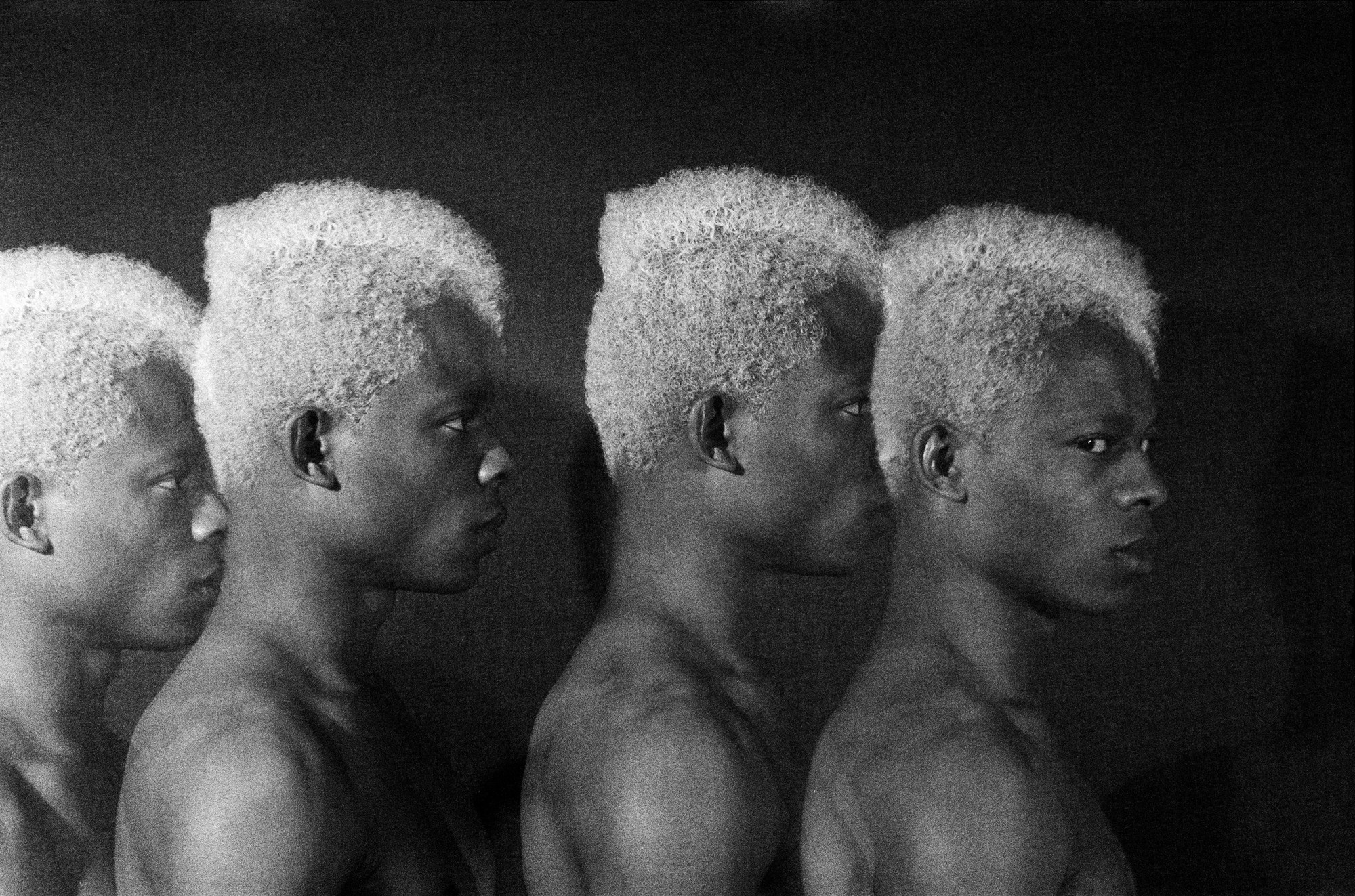

In fact, at some points in the exhibition, there are no clothes at all. For example, Rotimi’s gestural portrait “City Gent” (1988) portrays a Black nude figure from behind, their face obscured by a bowler hat. Nearby, a close-up, vein-stricken Black leg in diamanté heels, entitled “Heels” (1993), shot by fellow queer legend Ajamu X. Together, such works present an enriched vision of fashion beyond mere commodity, treating it as a performance of identity and its intersections.

Further into the show, some of the more contemporary names we know and love come to the fore. Nicholas Daley has installed his own listening station, “Knitted Roots” (2023), with a thick woven floor, a sound system and crocheted bean bags to sit and listen to his specially designed playlist. Opposite, Saul Nash has designed a sleek black tracksuit, “A Map of London” (2023), stitched with the names of Black British figures from every side of the Thames faultline: Stormzy, John Boyega, Lennox Lewis, Isaac Julien and more.

“I wanted to highlight the idea that people are layered and what first meets the eye may not match what you first assume about someone,” says Saul. “Looking closer, the garment is constructed from fine merino wool, so as to say that the tracksuit and people who wear it are more elegant than what is often assumed.”

Forming a history that’s still in writing, the works of these contemporary figures are placed close those of their forebears. For instance, there’s also Walé Adeyemi’s B-Side denim designs – as seen on a late-nineties David Beckham in that doc – shown in a glass vitrine, splashed with baby-yellow graffiti font and teamed with a matching, gilt-accented Nokia. As it goes, Walé had a longstanding relationship with Jason Jules and Harris Elliott. He had also crossed paths with Andrew Ibi while interning at Joe Casely-Hayford before launching his own label in the 90s. “I learned most of my craft and had my first understanding of the business through working with Joe,” says Walé. “It made it seem achievable when I saw what they’d achieved as a team.”

It’s heartwarming to see these puzzle pieces come together, and they segue neatly into a nightlife focus. Rather than treating parties as purely hedonistic forums, though, they’re understood as spaces of necessary reprieve for Black Britons seeking a place to congregate, with particular attention paid to community-oriented shubeens – the makeshift reggae parties of 60s and 70s London, which sprung up at a time when ‘no blacks, no dogs, no Irish’ signs were plastered across pubs.

One of the standout works, Cuyah: Look Here (2023), a film by Angela Phillips, takes us deep into the dancehall scene and the looks that came with it, annotating high-octane lamé heels, wrap mini skirts and crop-tops in ochre and gold with scene parlance or patois. “Set good”, “Outfit lookin’ trash”, “Heels above grung”, read the notes. Close-ups of costume jewellery, belly chains, blue eyeshadow and purple lippy feature throughout. “There’s a rich history inherited from Jamaica and the use of technology to flaunt fashion choices in detail has existed in dancehall culture since its inception,” says Angela. “Style commentary within a club environment was commonplace, which is reminiscent of what we see today.”

It becomes apparent, especially when walking through the Joe Casely-Hayford homage – replete with pearl and cowry-embellished tailoring, leather bodices and leg-of-mutton slide-off sleeves – that Black British fashion has always been enterprising and ahead of the curve. The rub is that it’s never been threaded into the fashion history books – nor major institutional exhibitions. Until now, that is. The Missing Thread does the good work, looking back to look ahead, and no doubt fuelling new generations of young Black Britons who need to see that others walked so they could run.

‘The Missing Thread: Untold Stories of Black British Fashion’ at Somerset House until 7 January 2024.

Credits

All images courtesy of Somerset House