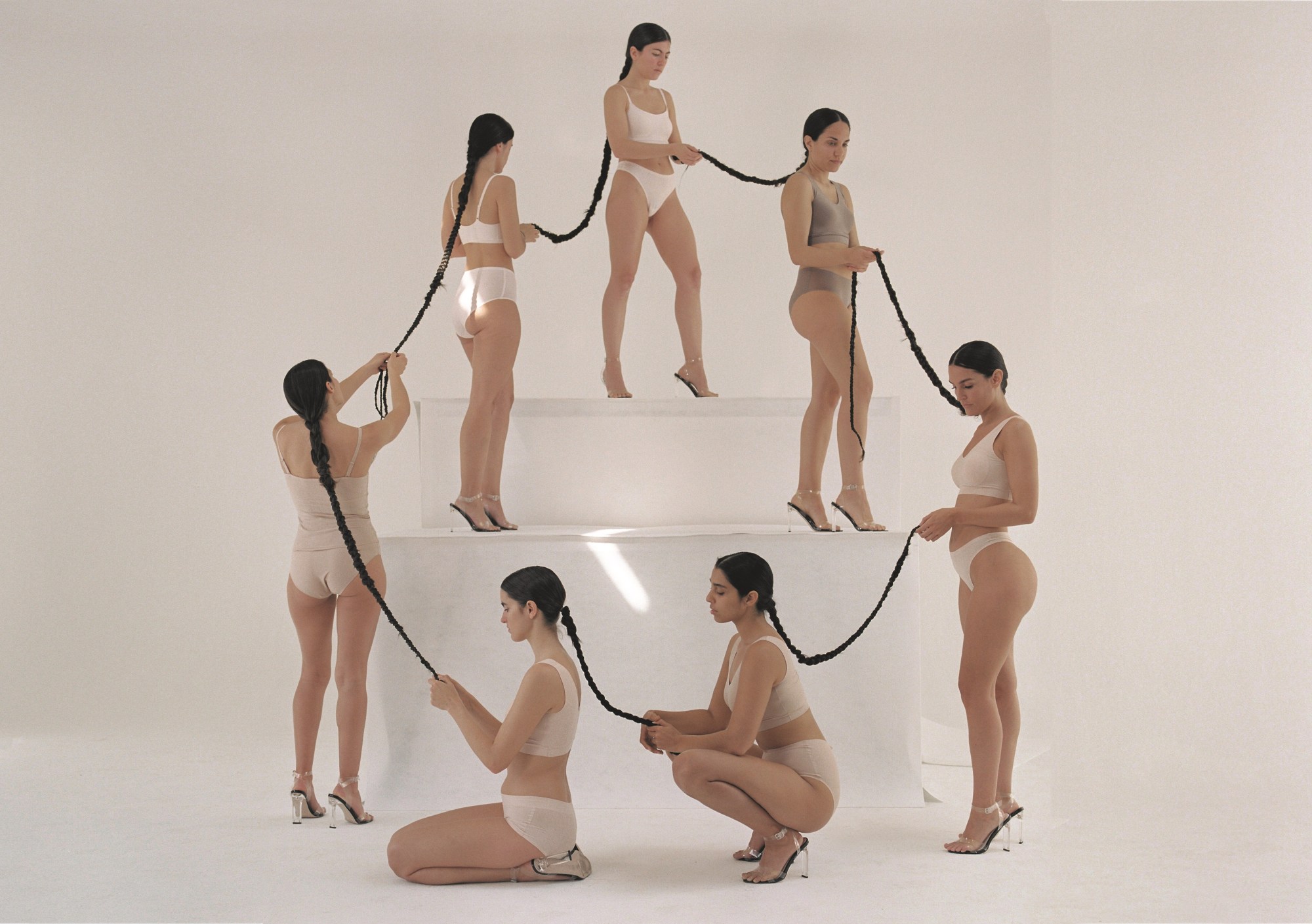

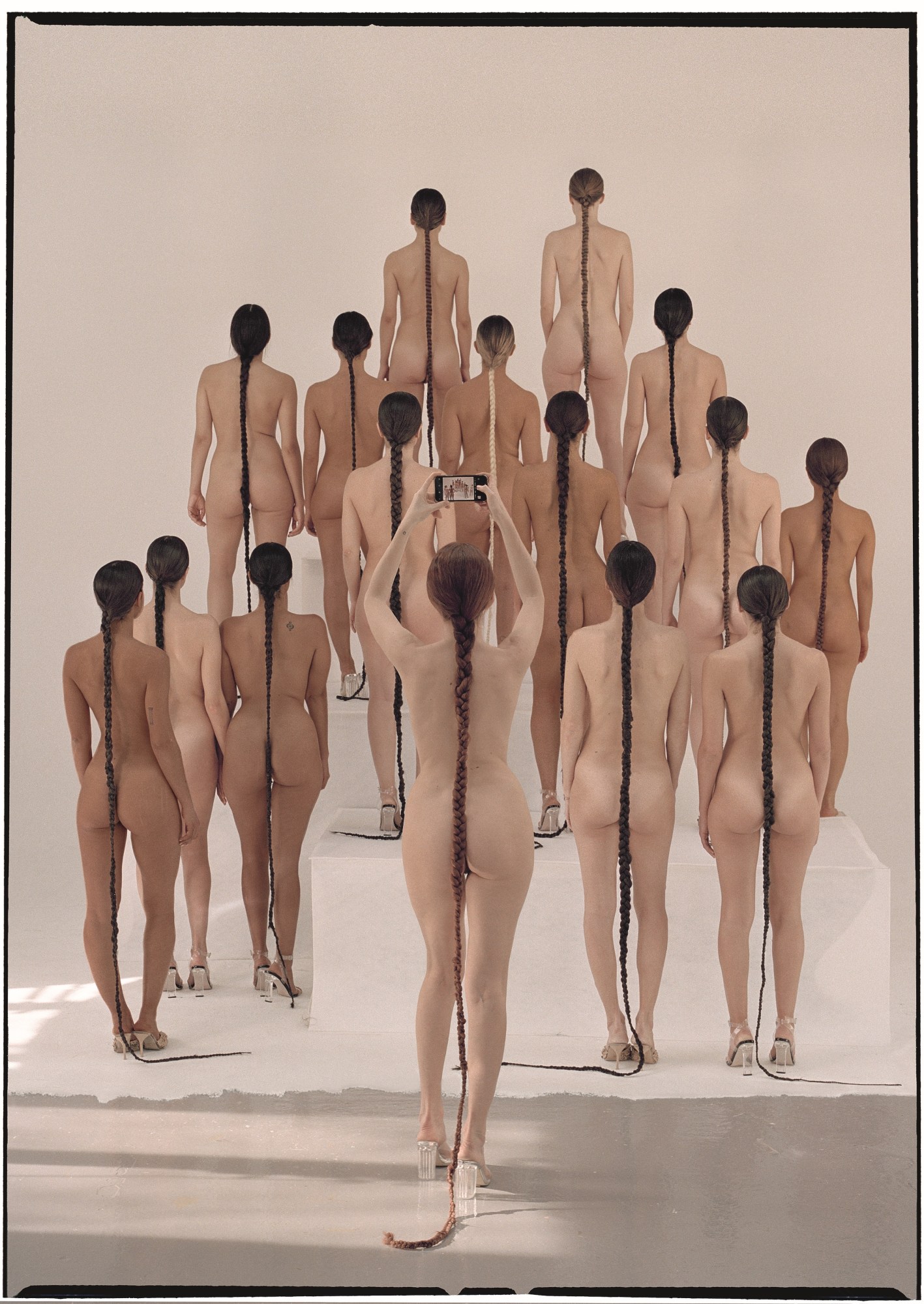

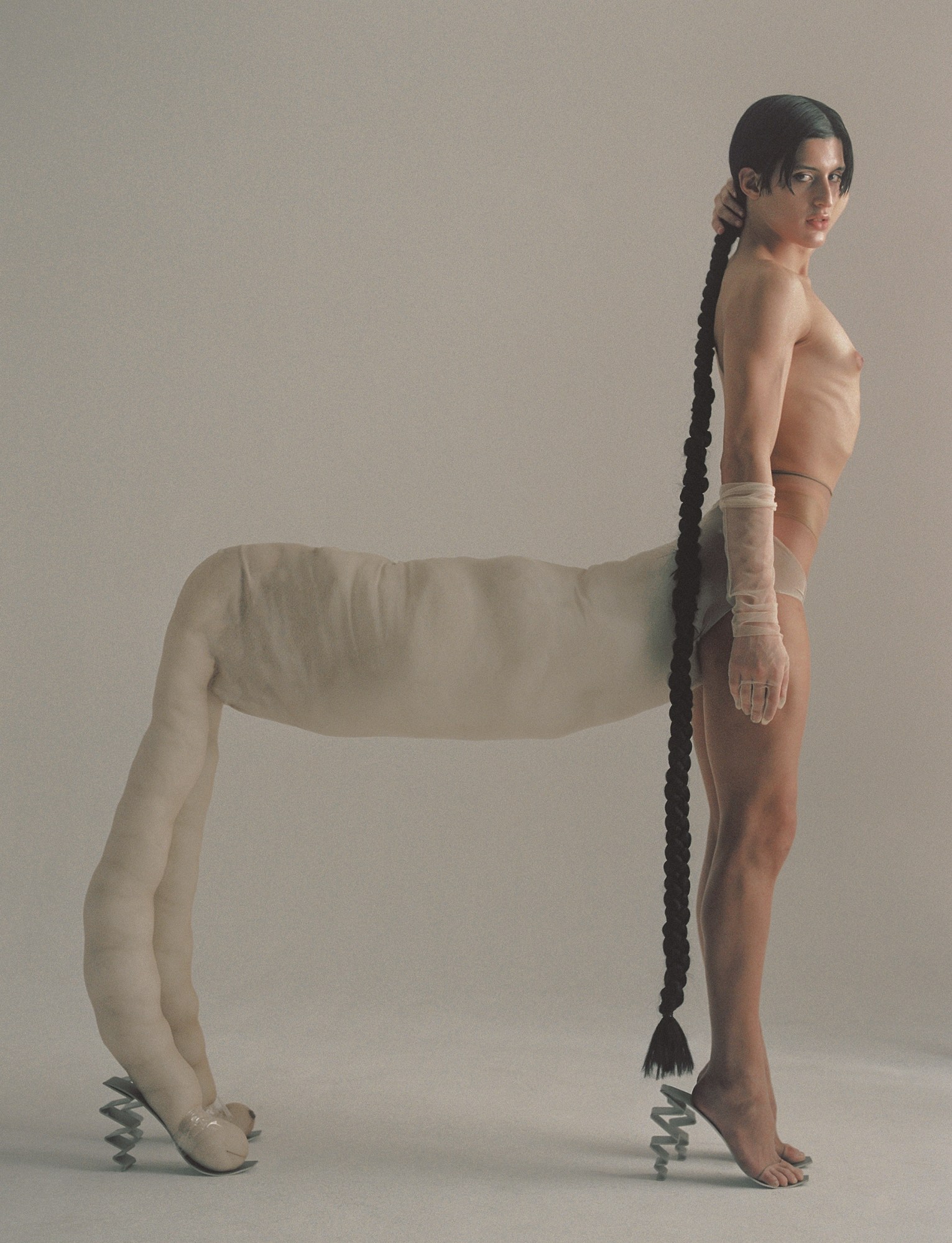

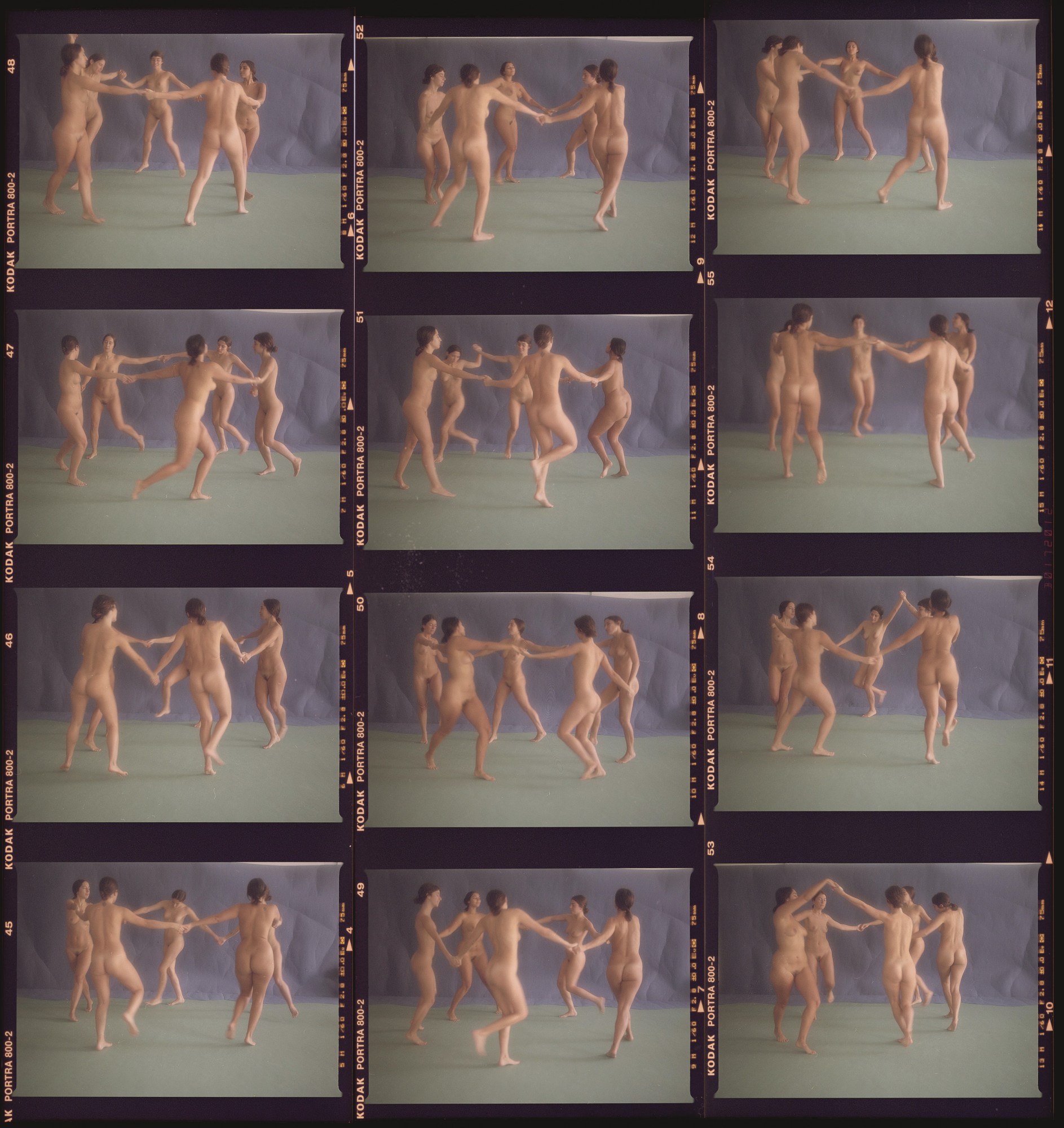

From intimate portraits to urban performance art, the through line of photographer Carlota Guerrero’s work has always been her stripped back sense of feminine reverie: rumpled sheets and broken shells, translucent tights and long braids, dusty floors and bare chests. It was this aesthetic that caught the attention of Solange Knowles, who commissioned Carlota to shoot the cover of A Seat at the Table (2016) and to creative direct When I Get Home (2019), helping propel the Spanish photographer into the limelight. From there Carlota went on to help shape the image of many of our favourite musicians, from collaborating with Arca on KiCk i to working with Rosalía on an undisclosed film project. Now, nearly five years later, all of these iconic, career-making photographs and a number of new, never-before-seen images have been compiled into one place. Carlota’s new monograph, Tengo un Dragón Dentro del Corazón (There Is a Dragon in My Heart), is out today.

Born and raised in Barcelona, Carlota has long been inspired by the city’s raw energy. It’s that, and the group of girlfriends she grew up with there, that she credits for shaping the surreal feminine aesthetic that she’s become known for. Carlota’s photographs transform the Mediterranean context into something earthy and erotically charged through meticulous art direction and choreography. The images often reinterpret cultural touchstones, too, like Henri Matisse’s turn-of-the-century painting “La Danse” (in which women twirl together, deliriously) or Alejandro Jodorowsky’s avant-garde film The Holy Mountain (known for its violently surreal imagery and mysticism).

Tengo un Dragón Dentra del Corazón documents the way Carlota’s style has evolved over the last five years. Ahead of the photobook’s release, we spoke to the Spanish photographer about her formative girl gang, the benefits of LSD and her journey to leaning more explicitly into sexuality.

How does being based in Barcelona influence your approach?

Everything is really raw in Barcelona — really lo-fi, relaxed. It’s easy to work here: it’s simple, small, calm, chill. Not having that much makes you creative with what you do have. The limitations of the city were a really good starting point, cause everything I put into my imaginario — into my world — was what I had, somehow. There isn’t this American ambition. There’s not this pressure of creating really big, complex things. Minimalism works really well here. Sometimes I see bigger brands trying to use that language, but with a lot of resources and a lot of money. They cannot imitate what you do when that’s really all that you have.

Which influences were formative to your approach?

My teenage group of girlfriends in Barcelona. One became a photographer and one became a fashion designer: Camila Falquez and Paloma Wool. That spiral of creativity we had growing up together created a foundation for everything that happened later. It was why I was so obsessed with depicting sorority and femininity and how women helped each other. There were no artists in my family; I had nobody to guide me to that path otherwise.

The book features images quite outside of the minimalism you described — for example, a striking ensemble of naked women amidst passersby on Las Ramblas. These are more maximalist, relative to what one might associate with your studio work.

I felt really brave at that time — it was like a turning point. I had been portraying a lot of ethereal women in the studio. And at some point I was like: Why am I doing this? Why am I depicting women in this super conservative way when I’m not conservative?! I felt really strongly that I had to make a statement and portray very sexual women, but as respectfully as I’d done the ethereal women. I wanted to put them in the same jerarquía [hierarchy]. Las Ramblas is the most aggressive street in Barcelona. It’s a really intense space where women never feel safe. I don’t walk alone there at night. So for me, putting that energy there was an act of bravery. Playboy had asked me if I wanted to do something with them, and I felt it was the right thing to do. So we created that performance.

Another surprising image is of a pregnant woman lying down at a bus stop — it’s one of your more recent visuals as well.

I’ve always had this feeling of, like, taking the women I portray to the streets. It’s something I always had in mind, but it started to happen more and more. The pregnant woman is my friend. Being pregnant during what felt like the end of the world — with masks and the sad energy — was such a contrast to the miracle in her body, and her energy was really, really bright.

There’s a very acute sense of choreography within the frame, of orchestrating a scene. How much are you planning versus improvising?

For me, guiding groups is much easier than guiding one person. It seems really complicated, but I feel comfortable creating big human compositions. In my social life, too, I’m the organiser. It’s like fractals in nature, how they move and how they work. It’s like God tells me, ‘This goes like this and this goes like that’. I always have some guidelines, but I’m really about the chemistry on set.

You talk about a vision that came to you during your first LSD trip in the introduction to your book. Do you consider psychedelics part of your creative process?

LSD has been a big guide for me, but the first time I had a major trip, that changed how I envisioned everything. I was with friends and we were naked by the sea. I could see rays of energy connecting us from body to body. I became obsessed with that vision, of an organism composed of all these bodies. I open myself up as a channel when I’m in harmony. What I was saying about the fractals, and about God, and the connection… It’s easy to call that ‘God,’ but I don’t know.

You cite “the nude as a spiritual force” but also “different levels of shame or guilt” associated with nudity, noting that you have been both a friend and an enemy of your body for 30 years. How do you negotiate discomfort with the body relative to wanting to empower it?

Once I realised the female body had only been depicted by men for centuries, and how that had affected us all, as women, the only thing I wanted to do was portray feminine energy. I wanted to diminish the power of the other vision, of men seeing us. I felt it wasn’t fair. As a woman, I never want anybody to tell me how I need to look or be. When I portray women, I’m trying to check on them all the time, if they feel comfortable, if they like themselves, if they’re just being a canvas for people to put things on them, if we are portraying their essence. My way of dealing with it is doing it the way I wish it had been done before.

There’s a celebration of the diversity of the female body, which includes a rethinking of the gender binary and what “femininity” itself can encompass. How does this affect your thinking and your work?

Feminine energy can be embodied in different shapes. It’s a beautiful thing. I portrayed a community of trans women in Cuba on an assignment for Sleek magazine, and they’re some of the most colourful images in the book. It’s very hard to be a trans woman in Cuba, as you can imagine. Their lives become a nightmare once they start the transition; they can’t work, except for prostitution, and run from the police every day. They impressed me so much though, because their feminine energy was unstoppable. It was threatening their lives, and still they wanted to dress in heels and makeup. The strength of their femininity — their performance of femininity — is much stronger than mine; it had to be constructed and worked on. It made me understand that this energy can be so fluid.

Credits

Photography Carlota Guerrero.