“The audience at Studio 54 almost upstaged Claude Montana’s fashions on the stage Wednesday night. Almost but not quite,” declared The New York Times in 1979. “Anybody with a sewing machine had done his best to copy Montana’s yard-wide shoulders and intergalactic space suits, but the designer who along with Thierry Mugler is one of the Katzenjammer Kids of French ready-to-wear, was a million miles ahead of his satellites in showmanship.”

The fêted French designer had landed in America to show off his designs, and the fashion doyennes of New York came calling. As the hippyish freedoms and disco buzz of the 70s slipped towards the power-dressing 80s, Thierry Mugler and Claude Montana had become two of the hottest tickets in town — often drawing scrums of people outside their shows desperate to get in. Both made clothes that turned the women who wore them into soldiers ready for battle: glamazonian in their silhouette and commanding in their stance. Both had begun at the same time, even sharing a flat for a period in the 70s before later becoming rivals. Today, the house founded by one remains a household name, worn by Kim Kardashian and Beyoncé, with rare archival pieces selling for tens of thousands of pounds. The other is relegated to the status of a footnote, nodded to by those in the know but without the wider gleam of fame or brand recognition that secures a place in the fashion’s hall of fame.

At the height of his powers, Claude Montana had been what design consultant and collector Steven Philip now calls an “Emperor” – one of those fashion gods whose status seemed unassailable, producing the designs that didn’t just embody but actively shaped the mood of an age. Montana got his start aged 17 when he moved to London towards the tail end of the Swinging Sixties. There he began producing papier-mâché jewellery. One of his pieces ended up on the cover of Vogue. Not content with jewellery, he returned to Paris a few years later and began working for leather house Mac Douglas. After the Battle of Versailles in 1973 – a legendary catwalk event that saw American designers including Halston and Stephen Burrows face off against French peers including Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Cardin – the Parisian fashion world was hungry for something fresh, brash, and modern. Out with the restrained refinement, in with the exaggeration and risk-taking fitting for a new era.

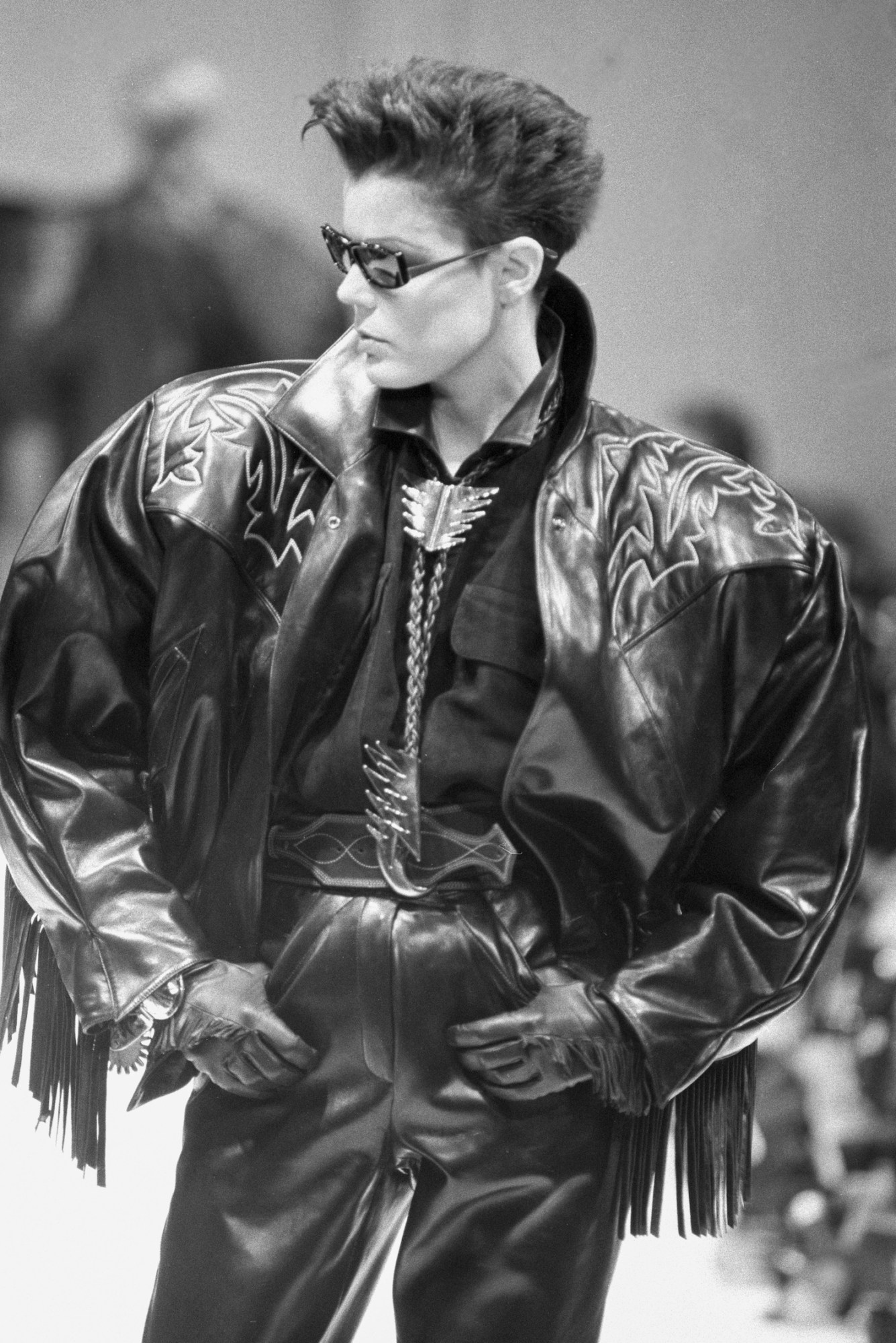

Montana made his entrance at the right time. Drawing on skills finessed at Mac Douglas, the designer’s own label House of Montana quickly established itself through its amped-up proportions, rich colours, and judicious fabric choices, with leather becoming a speciality. “The signature Claude Montana silhouette is really our signature silhouette of the 1980s: hugely wide shoulders above a tightly-defined waist, often with a short skirt or fitted trousers to emphasise the authoritative might of the upper body,” fashion critic Alexander Fury explains. “There are stories that women used to weep at his shows, because they saw a powerful vision of themselves in his designs.”

Although a similarly powerful vision was being exerted by Thierry Mugler, Montana had his own signatures. Steven Philip, who owns a small collection of Montana’s designs, characterises it as “comfortable power dressing.” Montana’s leather pieces had an aura of rock’n’roll, worn by stars including Cher, Duran Duran and Charlotte Rampling, but he also offered plenty of wardrobe options that those with deep enough pockets could wear without feeling too restrained. There was a knowing sensuality to his pieces, a melding of strict and soft.

Despite this ‘wearability’, other commentators also trace a distinctive note of solemnity – even iciness – in Montana’s work. “There is some similarity in silhouette, but Mugler was always flirtatious and fun, and Montana was deadpan serious,” Alexander Fury adds. “Watch those old shows: he plays Wagner and the models walk at a glacial pace. It’s about glamour and beauty and power – and it’s very, very po-faced.” Seek out interviews with the models who appeared in Montana’s shows and they also talk about his exacting requirements when it came to their walks and poses. Everything was part of a carefully controlled vision, a product of a top-down hierarchy where Montana directed and stage-managed every single decision.

Now, when we think about the 1980s, we think about a distant, long-dead era of fashion that nonetheless laid the groundwork for our own. Fashion designers became celebrities with adoring fanbases and widely recognised names. Brands leant in hard on the power of spectacle, putting on shows that were more like concerts, encouraging a wide cross-section of people to buy into the dream. Inspiration often came from the past in the form of references to Old Hollywood and 1940s and 50s couture silhouettes. Androgyny crept in too, with many designers melding elements of masculine and feminine dress, or mainstreaming clothing styles from queer subcultures including fetish wear. It was a time of new horizons and heightened excess, and Montana’s clothes were emblematic of this operatic age.

At the dawn of the 1990s, he took over as creative director at Lanvin, where his first collection was panned. Although he won around the critics in subsequent seasons, he was fired again after two years. The decade also marked a steady decline in Montana’s fortunes and reputation. He had a controversial personal life. Widely perceived as openly gay, in 1993, he married his long-term muse Wallis Franken. She died three years later when she fell from a window, and the authorities ruled it as suicide. Subsequent reporting by Vanity Fair relayed dark allegations about the nature of their relationship.

By 1997, a series of unfortunate business decisions and difficulties with diffusion lines also led Montana to declare bankruptcy, and the label was bought by French businessman Jean-Jacques Layani. Other than a small capsule collection in collaboration with Byronesque and Farfetch in 2019, the label has remained dormant. Montana has since lived in Spain and Paris, giving the occasional interview (in 2016 we learned that he’d “rather be Garbo than Marilyn” – choosing the enigma over the enduring symbol).

Despite his relatively incognito status, today, his fingerprints are still seen everywhere. “Marc Jacobs admires his work enormously and you can see the influence of Montana’s exaggerated sense of proportions in his own,” Alexander Fury says. “Rick Owens is a huge Montana fan – and although he also plays with Montana-ean silhouettes, he is also inspired by the quieter side of his work, by the sensuality of Montana’s choice of materials and the subtlety of his colour sense. Lee Alexander McQueen was inspired by him constantly, especially in his work for Givenchy.” Other fans include Olivier Theyskens, Nicolas Ghesquière, Gareth Pugh, and Martin Margiela, all drawn to his sartorial drama and rigorous craftsmanship in different ways.

So why hasn’t there been a Claude Montana renaissance? In the age of fashion nostalgia where images of Gaultier and Westwood designs ricochet around social media and brands including Paco Rabanne and Schiaparelli heavily trade on their heritage, why haven’t more people gone back to Montana? Aside from the complications of his story, Steven Philip thinks there just hasn’t been the right moment yet. Many of Montana’s key pieces are still privately owned by affluent clientele, and probably haven’t changed hands since they were first bought decades previously, he explains. Four years ago, he found a leather Claude Montana jumpsuit. “It was like a flight suit. It was beyond. But that [owner] was so wealthy, and she’d passed away. It was her daughter selling the pieces… A lot of ‘money people’ don’t sell.” If something of note happened – an exhibition, a revamping of the brand – Philip expects a lot more of Montana’s pieces to come out of the woodwork, or rather, out of the wardrobe.

It’s an opinion echoed by Hanan Besovic, who runs the popular fashion commentary Instagram account @ideservecouture. An avowed fan of Montana with a huge following, Besovic still thinks that social media alone can’t resurrect a reputation. “I think the society today, which is heavily focused on the youth, will not try to introduce Claude to 2022,” Besovic explains. “But I see that there is a great number of people that still remember Montana and appreciate his contribution to fashion.”

Popularity, whether newly acquired or finally regained, requires the right ingredients. Fashion thrives on coolness and social cachet, as well as a more general appreciation for design legacy. It moves like a slowly rising tide. Mugler’s showstopper pieces suddenly became the perfect red-carpet fodder. Gaultier’s trompe l’oeil body prints have spawned a thousand risqué homages. “Montana was never known for that one dress,” Steven Philip adds. “It was an ensemble look put together by him.” For the time being, that look remains something of a respected relic: a satellite still out there orbiting, not quite ready to land yet.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more fashion history.