In Portrait for Loneliness, a new show at Peres Projects in Berlin, painter Dalton Gata explores the malaise of diaspora: the way leaving one’s home creates a feeling of otherness and disorientation. Born in Cuba and based in Puerto Rico, this malaise is something the artist has wrestled with personally. He infuses the strangeness of this forever-unsettled status into his compelling paintings, using a bold palette and fashion-informed stylization to address charged themes of anomie and rootlessness, reflecting a singular brand of Latin American surrealism. The latest series functions loosely in continuity with his 2020 show, Diálogos Remotos, which also explored existential ennui and isolation.

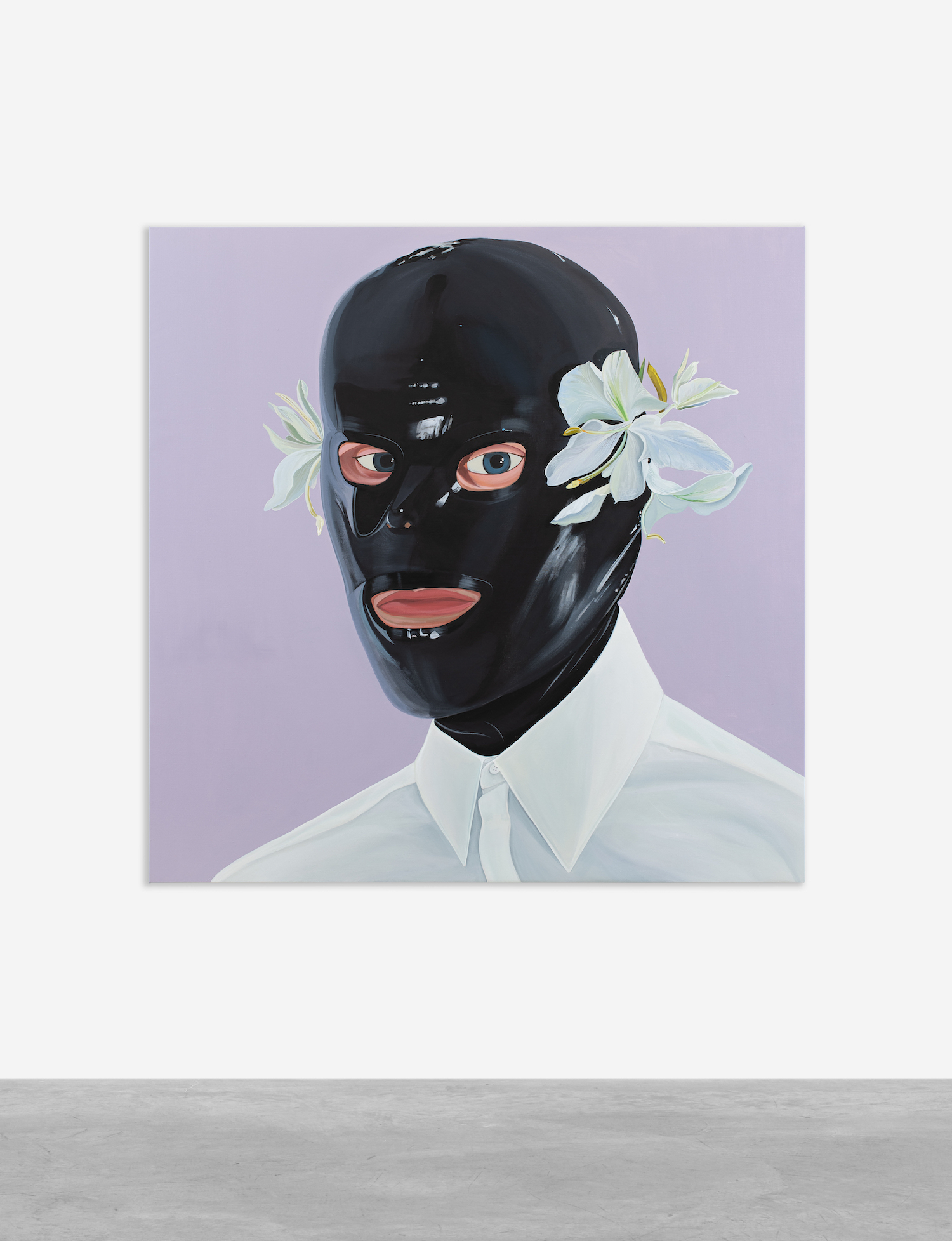

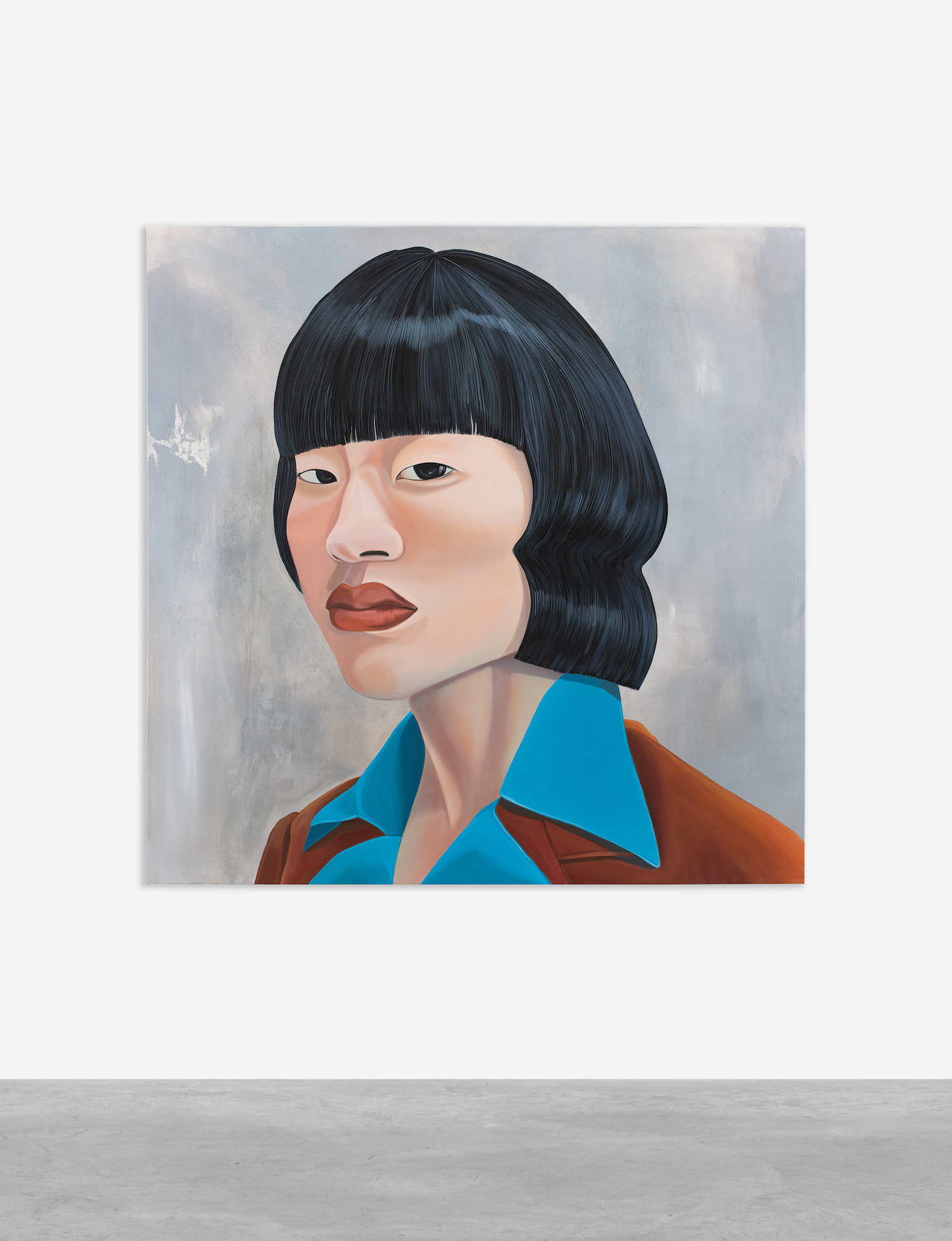

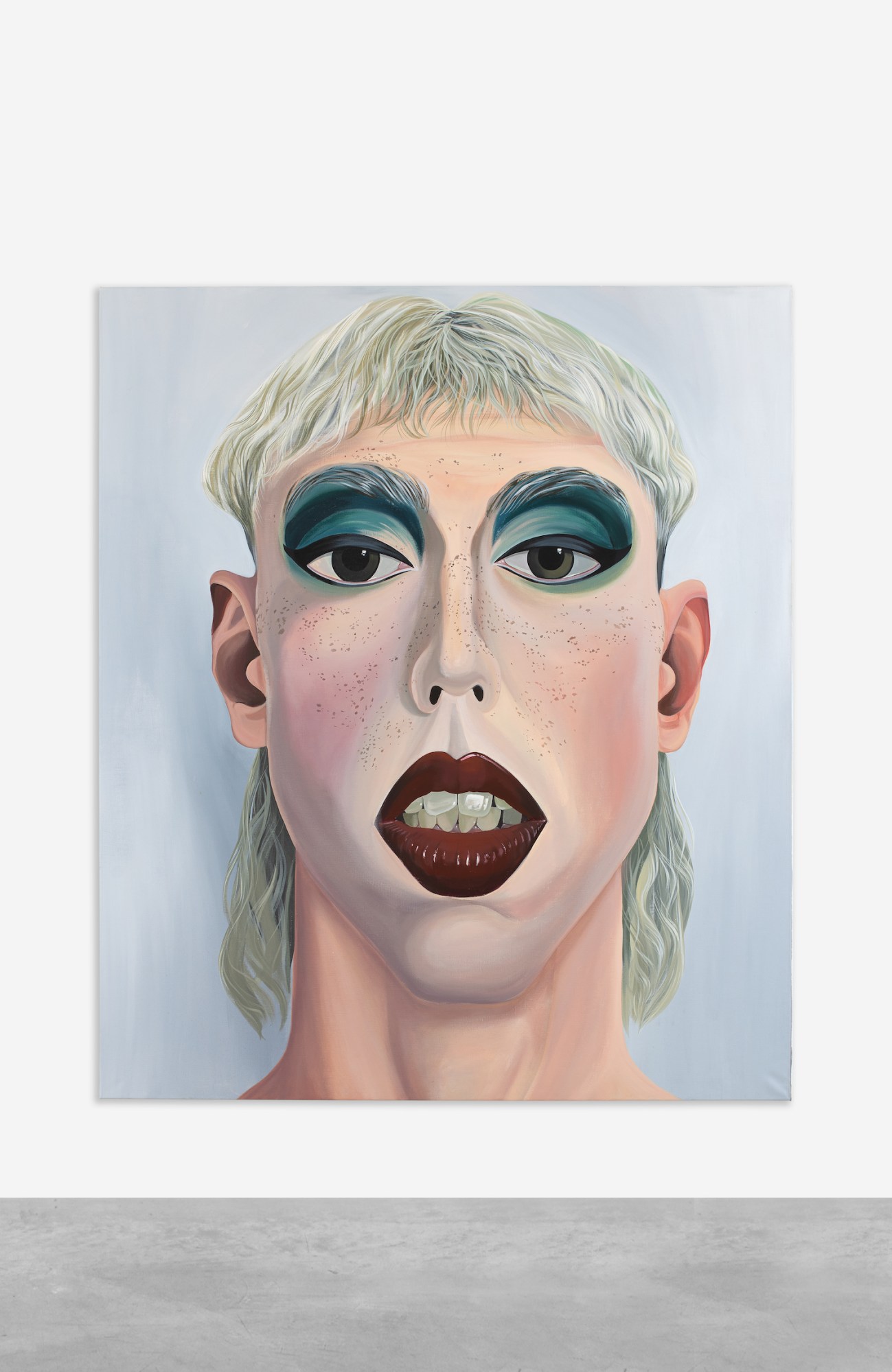

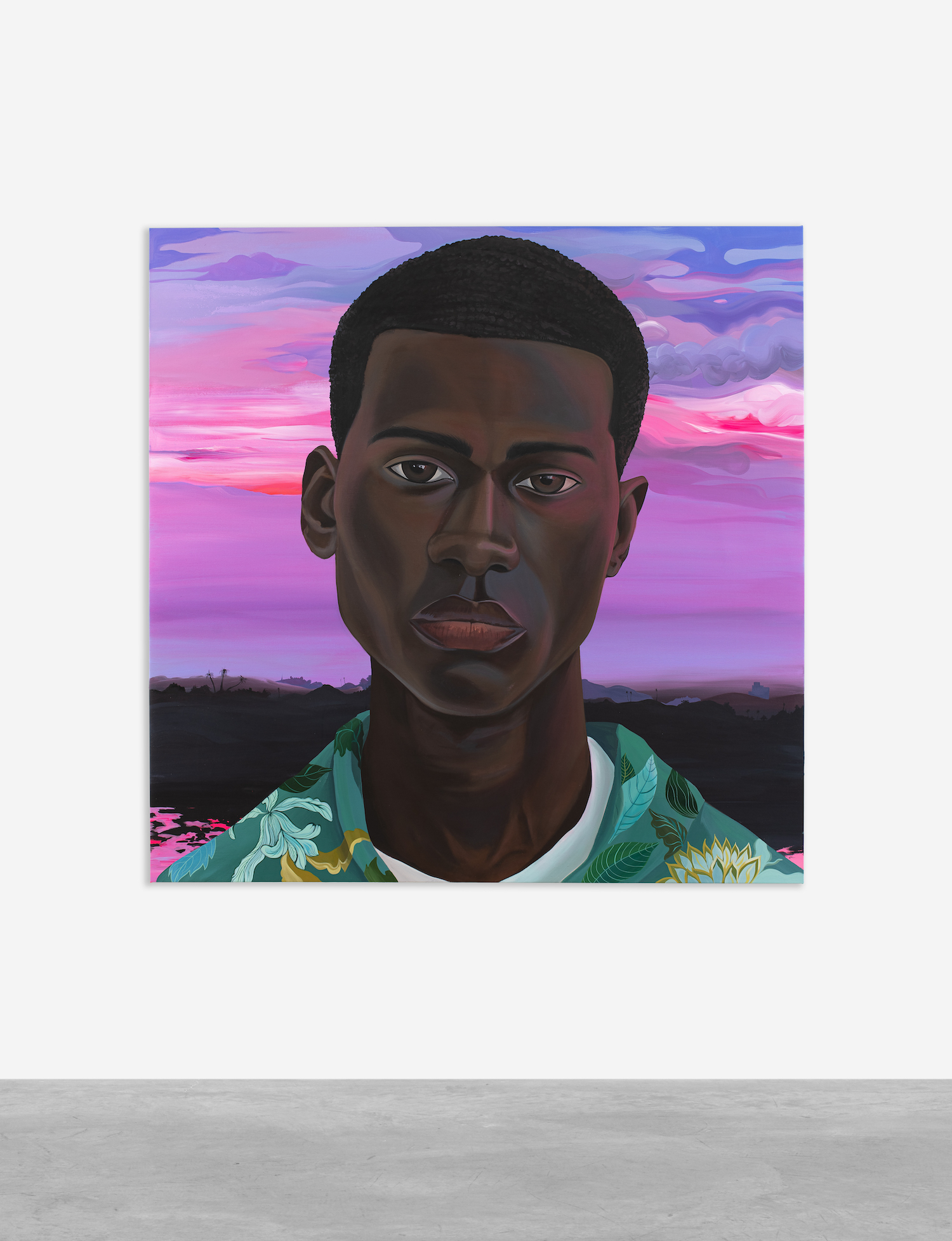

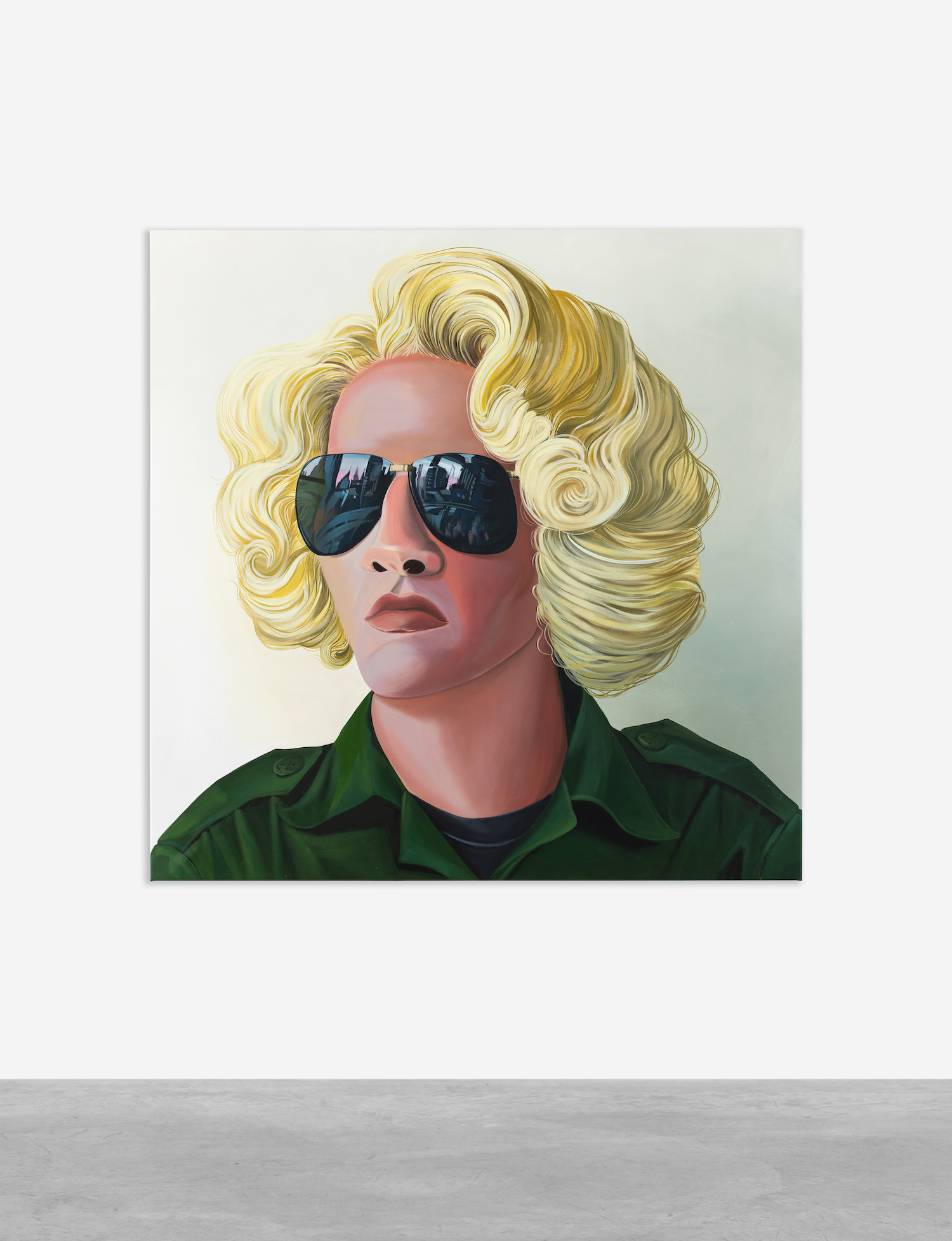

Portrait for Loneliness utilizes the passport photo format — a typically drab, pared-down representation —through which to consider the marginalized identities most affected by official forms of identification. The passport photo is a typology used to classify populations, thereafter allowing or denying their global movements and sense of agency. These portraits deliberately flaunt official border regulations and neutral backgrounds, hair pulled off the face, and absence of accessories or embellishment.

Over Zoom, Dalton and I discussed, by way of an interpreter, his disinterest in representative accuracy, Caribbean color schemes, and how the titular Jana of Jana of the Jungle cartoon was an early childhood icon.

You began in fashion, before becoming a painter — what spurred that transition towards visual art?

I got a degree in fashion design in the Dominican Republic, and started a business, which I found very hard. Producing garments for differently sized customers, accommodating different tastes, and depending on a team of people was all challenging. I was dealing with poor sales, and I grew progressively disenchanted. Most of my friends in the Dominican Republic were painters, and I was actually living with a painter at the time… the transition was somehow organic. I’d been drawing since I was a child, and I was sketching a lot for design and composition classes during the first year of my fashion degree.

When did you really commit to taking on a new creative path?

My first ever exhibition was in 2011.

Two years ago, your exhibition at Peres Projects featured many of the themes in the present show too. Could you talk about the things that preoccupy you? What is a through line in your work?

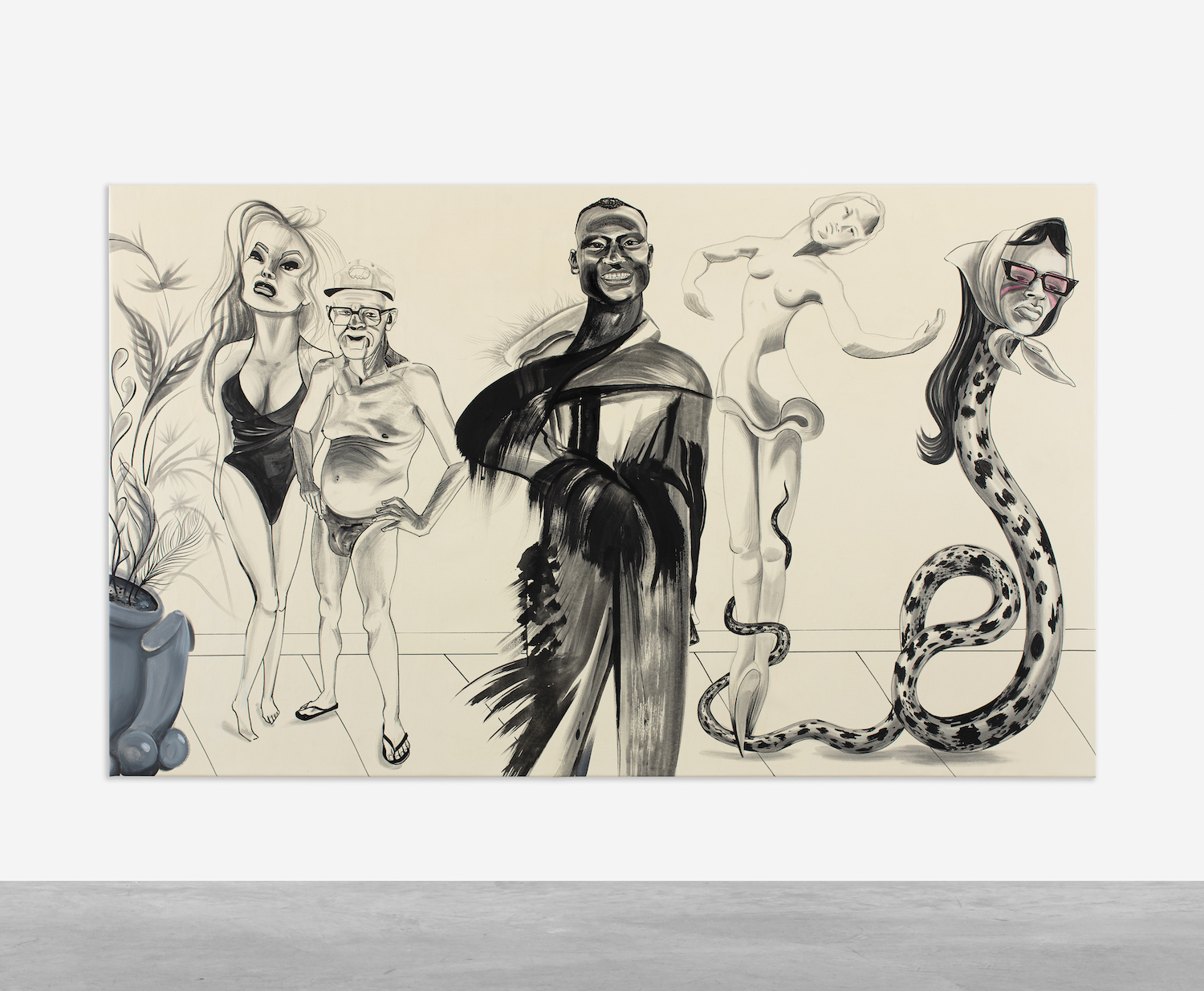

When I look at my first paintings, I realize the work I was initially producing had an obvious link to fashion, or like a “fashion gaze,” in that I was mostly making portraits of very stylized-looking people. But thinking on it today, in the context of my wider body of work, I realize that the people I was portraying weren’t just stylish — they were psychologically interesting. They were out of the ordinary not only through the fashion choices, but through the marginalized communities they came from. Marginalized groups are fascinating and worthy of being celebrated: they have always been my focus. I portray mostly the LGBTQ+ community, but also migrants, Black people, prostitutes, people of ambiguous gender. I often end up painting friends or lovers, but also anyone who just happens to draw my attention. People from social media also end up in my paintings.

Once you’ve identified your subject, how does it play out from there? Do you do sittings, take photographs?

I never work with live models, even when painting people I know. I just don’t have the time to. When I find an interesting subject on Instagram or whatever, I’m not replicating the person exactly, in a way that produces a recognizable depiction. I’m mostly just interested in some features, like skin tone, or physical peculiarities, without fully copying. Mostly it’s the gestures that attract my attention. What I paint from the reference subject is, in most cases, just the face, or the accessories that the person is wearing. I’m collaging a face to the character that I’m already building or imagining.

I’m not interested in: I want you to paint me… I want my image to be immortalized. Definitely not! There is no interest in accuracy, because the focus should not be on whether the person is recognizable, but on the discourse I’m trying to convey. When I paint a person, it represents a community. Even when I paint a group, this group represents other multitudes.

For this newest series, why the typology of a passport photo? What was interesting to challenge or reinvent?

The passport idea is the result of different situations that coincided in my life. As I was thinking about the Berlin show, a family situation unfolded… four cousins of mine were leaving Cuba, three doing so in the most dangerous manner, which involves going through an undisclosed Latin American country and crossing a very dangerous river. Obviously doing all of this illegally, and dealing with what that implies. They were leaving behind their whole families, including wives and children.

Parallel to this, my own Cuban passport expired, which is the reason I couldn’t be present at the Berlin opening. I had to go through the motions of getting a new passport picture and work through that bureaucratic process. I found the regulations and rules regarding the format of the pictures — what is allowed to be included in the background and rules around makeup — funny… As my cousins were doing the illegal variant, I was in the process of the same end goal by different processes.

The paintings have very anonymous titles: just “Portrait number four” for example.

The loneliness of the migrant is not only about leaving everyone behind, but also this coldness of bureaucratic procedures. My paintings are not a typical passport picture: they’re “rejects,” because they’re not complying with the regulations — the most “rejectable” pictures possible, based on my research. Yet they portray people as they really are: your individuality and your makeup and your jewelry is what makes you what you are. Passport pictures are in fact subverting that.

There’s a painting where the subject is covered with a garbage bag, another one is in a mask, another one wears way too much makeup. What I’m reflecting on is the fact that we all, as individuals, invent or create a character or a superego of sorts to live more comfortably in society, to pass through without trouble. And it is kind of ironic that this armor sometimes leads to even more loneliness or social rejection, because these personas we build are too strong for society to accommodate, so they end up driving you further away.

Can you talk about your use of color: how it can defamiliarize in a surprising way?

I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about color… it’s the last thing I consider when approaching a painting. The colors relate to what I’m trying to say in the painting but, for the most part, they relate more to what my emotional state is at the time. That’s where the emphasis is: how I’m feeling. For example, back in the beginning of the pandemic, during the first worst phase when thousands of people were dying and everything was forbidden and so on… it was the first time I produced a black-and-white painting. Colors, for me, tell their own story: they convey an emotional background. It’s just something that comes naturally to me; cognitively, I’m preoccupied with other things in the painting’s composition. I’m certainly not afraid of color, because I’m Caribbean and have lived many years in Puerto Rico and in Republica Dominicana.

Your psychological state formulates your color story, but other people provide physical references. How much are you infusing yourself in this idea of different masks or personalities? Is this a bit of a self-portrait exercise too, ultimately?

That self-portrait idea resonates. I say — partly in jest, but partly seriously — that all these people I’m painting are actually all myself. Like, all these characters are actually self-portraits. It’s true, to an extent… but also, I see this as me trying to paint my community or my crew: a circle of friends, a representative subculture.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

Your work is described as “surreal” — how do you create this atmospheric in-between-ness that is both recognizable and otherworldly?

It definitely comes from childhood. Picture growing up in Cuba in a rural area, in a very small town in the fields, in a very Catholic, very conservative, descending-from-white-Spaniards family… I myself was a sort of surreal character for them. That’s the way they made me feel, or the way I perceived being treated as a child. I was always in my own imaginary world. I wasn’t playing with my cousins… who weren’t exactly around my age, so maybe there was a bit of an age difference to account for, but they were not interested in playing with me. I definitely had this impression of being weird. The way I look at it, it is not particularly dramatic or traumatic, because I existed in a parallel to the real world, one that has accompanied me to this day into the paintings.

I can still see that boy who played on this family’s farm with the dog, climbing trees and pretending to be the main character from the comic book Jana from the Jungle. I see myself as a sort of reporter of histories that have only, like, streaks of reality. I’ve never been interested in conventional society.

As we’re speaking, you’re in your studio space. Do you have a daily practice or certain rituals as a painter? Or do you just work whenever it feels right?

I wouldn’t say that I have a ritual, but I’d describe my practice as just paying attention to what is happening socially and always being preoccupied by the project at hand. The process is: first I figure out what I want to say. Then I look among my references. I have a folder with images from the web and social media that I’ve been collecting. I go through these to compose the painting.

Lastly, let’s talk about the choice of title of the show: Portrait for Loneliness.

The title relates to the alter ego or persona that I just mentioned, which people build in order to find a place in society.

But also, when you’re about to leave the country and you’re in the midst of this bureaucratic process, you’re all excited to go and get your passport picture because it’s a first step in this new journey and adventure. Doing all this, you’re ignoring the loneliness that awaits the other end of this process.

My loneliness is not only what every migrant has experienced in their first years away. I left Cuba at the age of 19; it’s been a lasting burden I’ve been carrying around. I’m a very friend-oriented person, so it was hard to process. But it’s also something that I even feel today, after all these years, because sometimes it’s just going out and realizing that there’s this stigma with my accent. It’s not like Oh, poor me in this terrible solitude — but more of a certain alienation that just remains. It’s part of the trade: you give up that comfort for all the other opportunities that you’re receiving.

‘Portraits of Loneliness’ is on view at Peres Projects through November 11th.

Credits

Images courtesy of Peres Projects