Matthew Smith fell into documenting rave culture via the usual circuitous route: art school, clubbing, festivals, disillusionment with everyday life, the possibilities offered by sound system culture, the freedom, the ecstasy, the hedonism. Simultaneously, there was also the feeling that the youth was being demonized. And from this came Smith’s desire to create a narrative that showed his generation in a more positive, honest, and respectful light.

His new book, Exist to Resist, was funded entirely on Kickstarter. It lifts the hedonistic lid on the scene to reveal the politics of dancing, and how the scene resisted the government of the time. The early era of rave was all about cutting loose and dancing for days, but after the Tory government began to criminalize the free party scene and the travelers who formed it, politics were thrust on the partiers. A generation of ravers became opposers who dared to stand against the conventions of society.

More than a coffee table book, Exist to Resist is a reminder of a time when the power of youth could challenge the power of government. And it’s more relevant than ever right now.

What’s the relevance of looking back at this time now?

The basic idea behind the project is that we believe that photography has the power to show people how things were in order to see how the future is evolving. Photography is great like that; as an art form in itself, that is one of its biggest strengths. It can really get people thinking, especially when it exists outside of vanity, celebrity, or the purpose of selling someone else’s product. Many of the pictures in the book exist because a small bunch of friends got together to say ‘no’ to government as they felt that was the responsible thing to do. And that is particularly what makes them extremely relevant in the long term and right now.

Similar frustrations exist today.

Increasingly it seems that we live in a country with a failed democratic administration that has had its day. As a nation, we need to evolve government and create something new that is better-suited than the tired and morally corrupt options that are in place now. The proof of that statement is everywhere. From the new mortgage rules imposed on the people after the last manufactured recession, to the results of the Chilcott Enquiry. From the Bedroom Tax to the ongoing destruction of the NHS. From the licensing conditions imposed on Fabric recently to the Investigatory Powers bill that grants government the right to spy on the public’s digital behavior in a way that is completely anti-democratic. From the lack of response to the refugee crisis to our Prime Minister holding hands with Donald Trump in the White House. This list could go on, but maybe it should end with the success of the festival world 23 years later and all the amazing people that it brings together in such numbers.

What was your first introduction to rave culture?

It was a cumulative thing as the music evolved and combined with the culture. I grew up in a small town in the west [of England] during the 80s — it was a microcosm of all the different style tribes that were around at the time. Then I got a job in a local pub that was a hangout for all of them — bikers, punks, skinheads, hippies, arty types. There was a great community of young people in the town all inspired by the music and fashion of the times.

My cousin started a club called The Gap, and we used to play all kinds of music from bands like Alien Sex Fiend, King Kurt, and The Cramps [as well as] disco, funk, and rap from Chic, the Sugarhill Gang, Whodini, and James Brown. [We played] electro from Divine to trad jazz from musicians like Louis Jordan and Cab Calloway. Everybody used to dance to everything. And of course there were major house parties in farmhouses and barns in the villages around the town.

My girlfriend at the time went to art college in Liverpool, and when I hitched up from Somerset to go and see her, we’d go to an acid house night there called Bigmouths. Then I went to art college in Stoke, not far from Manchester, and we started to go to acid house nights that were full of strobe, UV, and smoke as records like “Pump Up The Volume” and “Paid in Full” were coming out with amazing sampling, and also Lil Louis’s French Kiss acid house classic. Reggae also had a big influence on everything.

One of my friends from Somerset who had been living in Stoke for a year or so was running an after-hours rave club called Introspective that didn’t begin until 2 am. It was full of guys with skinheads and red tracksuit bottoms with their tops off just worshipping the music. The girls were the same, just in bras, having it. It felt like being at some kind of religious ceremony — all hands in the air and pumping music. Sasha started his first big residency at Shelly’s in Longton around that time, and we also had a student society so we could get a minibus and drive to Manchester to go the Hacienda, as one of our friends was working in the cocktail bar of the club. In my experience, though, the subsequent myth didn’t really approach the reality of being in the club.

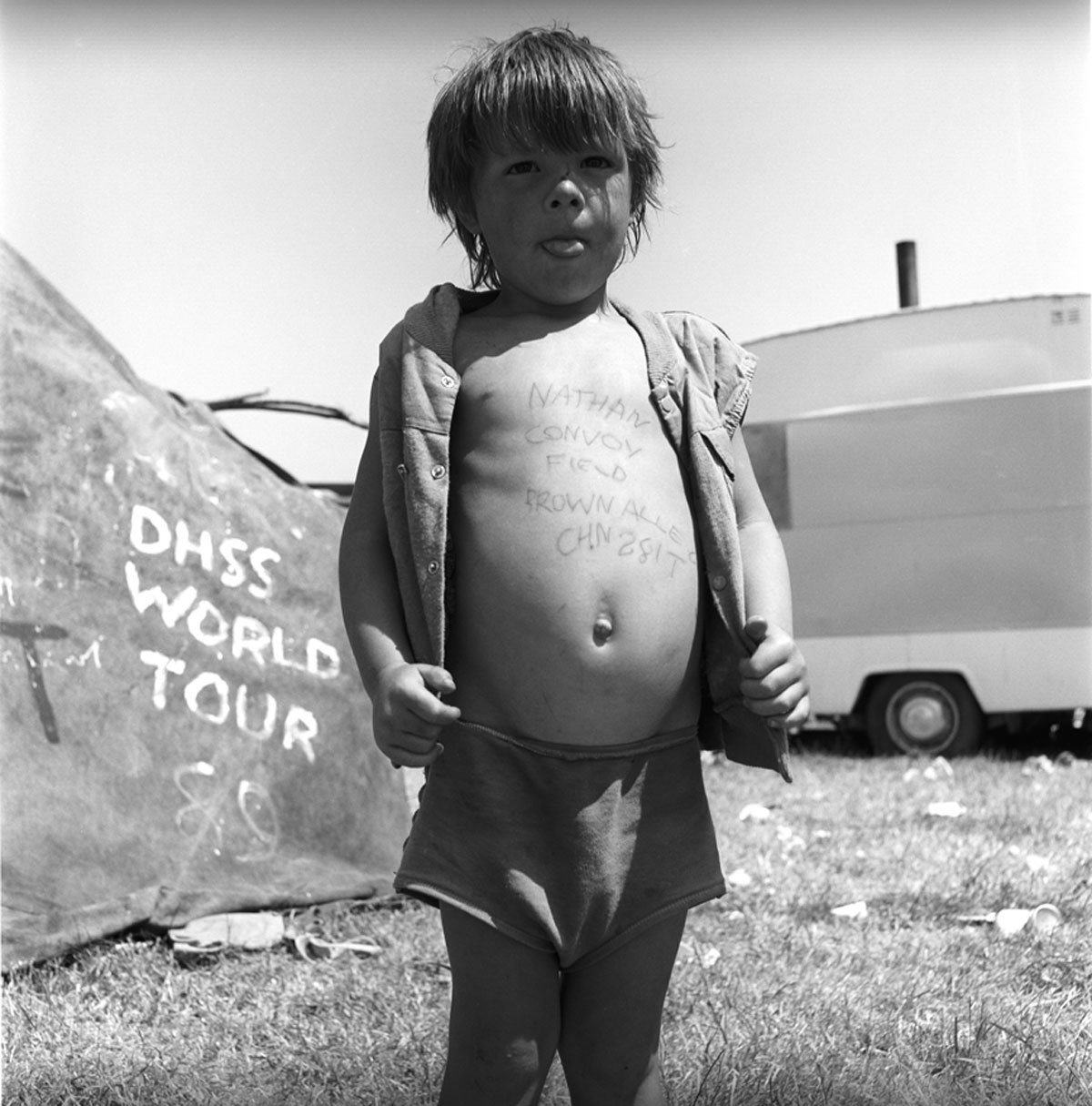

What really did it was Glastonbury in 1989, when I went to work there and photograph it as part of our first big independent summer project whilst studying for my degree in photography. Rave hit Glastonbury in a big way that year and dancing to rigs playing in the Convoy Field on the outskirts was an amazing experience — just full-on. Then there was a big red decker up in the Greenfields disguised as a cafe and underneath the tables covered in gingham tablecloths were hidden massive speakers. I danced there for 10 hours solid through one night, the dawn and into the next day to the deep house music, with a bunch of people who all seemed to have become part of my family without ever even knowing them during the course of that time in front of those speakers. Over the next couple of years, going to DIY and Circus Warp free parties in Somerset, and Lazy House parties in Devon, just became part of the great summer experience of growing up in the west.

Why did you start documenting and photographing the scene?

I shot carnivals in Mosside and Notting Hill for my degree show, and that started an interest in photographing music culture. Then I went to work in London for guy who was a music photographer — he worked for the Rolling Stones in 60s — and got a couple of freelance jobs working for Polygram, where it became evident how just planned the sale of commercial music was. Then Castlemorton happened. I was getting calls at work from friends who were there. I couldn’t go, but clearly what was happening was huge, the culmination of a whole series of massive parties that had been happening across the country as rave culture was growing, gathering strength and popularity. When it became apparent the culture was going to be outlawed, it seemed that the best thing to do was to make pictures to counter the demonization of that culture by politicians and the press.

Would you describe yourself as an insider or outsider when you were documenting it?

You might be an insider to one person and an outsider to another, but when you have a bunch of speakers with you, it made it all ok.

What story do you hope your images tell?

You have to kind of leave that up to whoever is looking at them. But the general response has been that they come from a time when there is a lot more freedom than there is now.

Do you think politics was something integral to the rave scene? Where did it come from?

Politics became integral to the rave scene when they criminalized the culture. The crucial link that interests me was the success and popularity that rave brought with its links to people seeking to house themselves outside of the mortgage rent trap. The mortgage is the most powerful element in the architecture of social control that there is, because people have to buy into it voluntarily. Maintaining control over people’s security and their homes is vital to keeping people just where government wants them. During the lead up to the criminalization of raves and the mobile lifestyle, the government was selling the idea of home ownership to the public in a big way. With its very existence, the traveler-raver defied that process.

We live in a feudal country where most of the land is owned by a very few people and land ownership is regulated in a highly oppressive way, leaving very little room to live a mobile lifestyle. Just as the gradual enclosure of land has led to massively increased property prices, the enclosure and control of culture has enabled a very profitable industry to arise from that process. Culture didn’t come into existence because it was granted a license by a local authority, it happened of its own accord. That is what makes culture more powerful and democratic than politics, and is the reason that government seeks to control it.

I noticed in one of the pictures a placard that says “resist to exist” and you’ve flipped that around for the book title. Why?

Because freedom is inherent to people. It is a right that exists outside of any political permission, although that clearly comes with a lot of individual responsibility. Existence comes first, and there really shouldn’t need to be resistance in a successful democracy, because democracy should provide for people’s lifestyle choices. Unfortunately that isn’t the case, which makes resistance necessary. We might do a reprint though and include a whole bunch of ephemera that I have also collected along the way and call that Resist To Exist. The words are kind of interchangeable at the end of the day.

1997, when the book ends, is when the Labour government was elected. Did that feel like the end of an era?

Sadly, it did not feel like the end of an era. It is telling that one of the images depicts the words “Fuck The Election” sprayed on the wall of the National Portrait Gallery, taken only the day before Blair got into power. It was much more of a case of same shit, different day. Recent history has proven that with catastrophic consequences for millions of people’s lives. Conversely it has made a lot of corporate organizations a huge amount of money and provided the excuse to remove a lot of basic freedoms in the world.

Do you think we mythologize rave too much?

Being a very practical person, the reality of rave means some pretty hard graft. It means fuel, transport, carrying heavy speakers, putting up tents, and clearing up other people’s rubbish when you’ve been awake for over 24 hours. It means dealing with DJs who blow your speakers up and waltz off afterwards thinking they’re something wonderful.

It means balancing on ladders putting up expensive lighting kits that people have worked hard to buy. It means networking and talking and planning to create amazing performance and environment in amazing places. It means a lot of people coming together to do something amazing for a whole random selection of people they’ve never met because doing it is just amazing and what happens can be phenomenal in a whole variety of completely unpredictable ways. It means facing the prospect that all of that goodwill and mutual cooperation might mean that someone will set a vicious dog on you, or smack you over the back of the head with a riot stick, or steal your phone to pry into the everyday details of your life like a data rapist of the worst kind.

What’s your favorite image and why?

My favurite image is only available to look at in the book and has not been published in the run up to its release. You can ask me that again after it’s come out and I will tell you the story behind it. But for now: join the resistance, buy the book, look at the pictures, read the writing, come to the show, take the trip, and most of all, enjoy the ride.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography Matthew Smith