Elyse Fox’s imagined impression of mental illness was a stereotypical image of a sad girl in a white jumpsuit, sitting slumped against the windowsill of a psych ward. She had no idea how the girl got there or what treatment she was receiving. What’s more, no matter how many different scenarios she ran in her head, the girl was always white. Sure, Elyse had been feeling pretty miserable now for a while, but as a young, black, mostly functional woman who looked nothing like the very sick person in the image, how could she possibly relate?

“I remember being on the phone to my dad — I must have been about 10 or 11 — saying to him that I felt really sad. He asked me why, and I replied, ‘I don’t know, I’m just always sad for some reason.’”

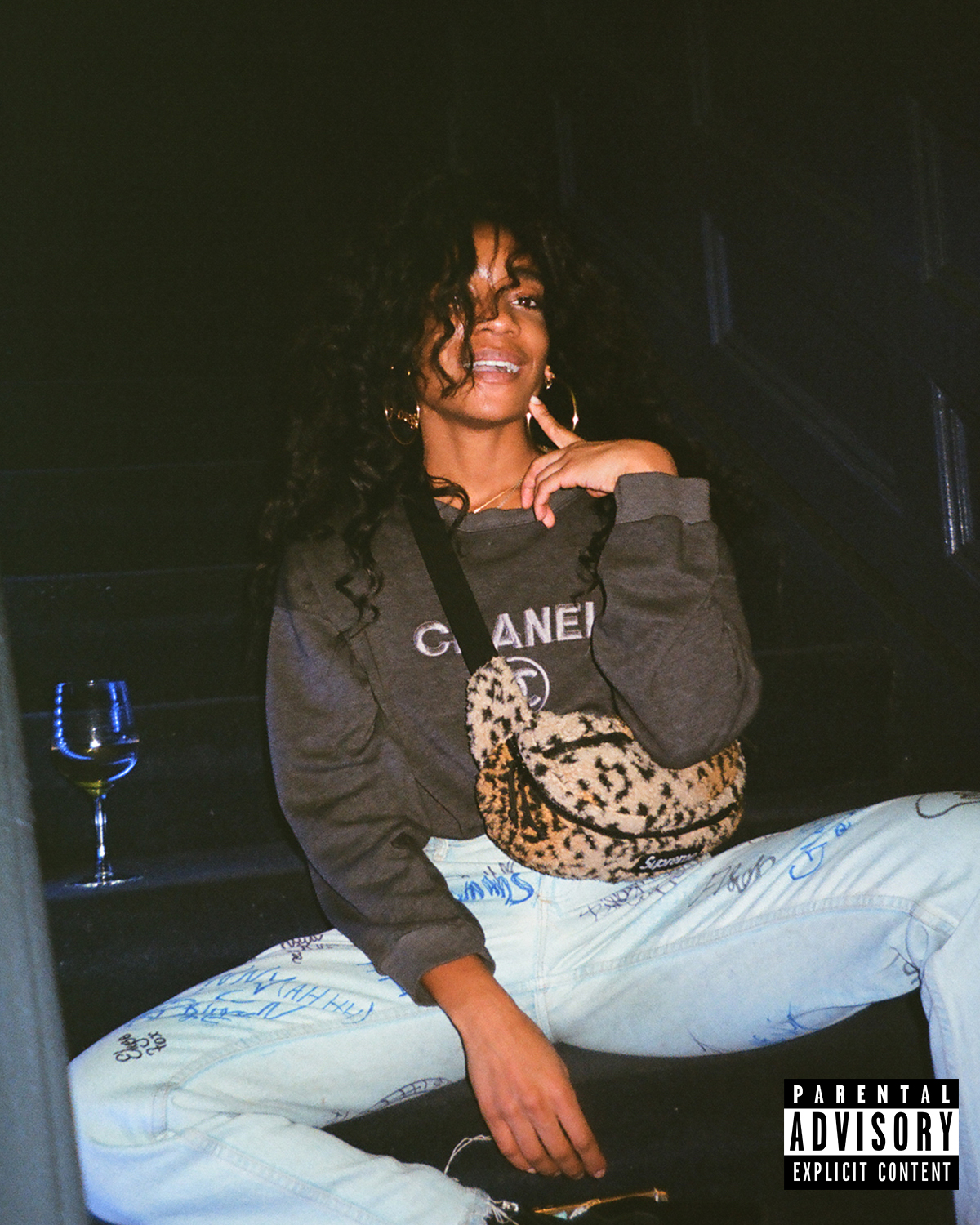

It’s a rainy day in New York, home for the 27 year-old filmmaker after four tumultuous years in LA. But it’s a “good day” she reassures me. She’s laughing, at least — a marked departure from the picture she paints of herself two years ago. “I’d just got out of a really bad relationship. I was completely suicidal and not loving myself,” she says incredulously, almost as if she’s talking about some entirely other person. “I was at the bottom of the barrel; I had two options, really, and I chose to get help.”

“Growing up, we never really spoke about mental health,” she says of her Brooklyn upbringing. “I’m a first-generation Caribbean woman. The topic of mental illness was just never discussed in my home. When I was younger, my mum had symptoms of depression. I’d heard the word “depression” around, sometimes kids would call each other “depressed” as a joke and the teacher would correct them. But otherwise I had to educate myself on what it actually meant.”

In 2016 Elyse moved back to New York where she says she had to re-learn to love herself. It’s important to note that this wasn’t just some bad reaction to a break up; two years prior Elyse had been clinically diagnosed with depression. Storm clouds had been gathering overhead for a while, she just didn’t have the right tools to forecast it.

When it came to managing her own symptoms, Elyse found respite in art. She wrote poetry, took photographs and made films, which she’d then post online, signing off each time as “Sad Girl Elyse” — a nod to the viral sad girl internet trope. “The Sad Girl thing just felt right,” she recalls. “At the time, I didn’t feel like I was taking a particular stance, I was just like, “This is me”. Now I realise it was a cry for help.” No matter how alienated or misunderstood she felt, when then was nobody to turn to IRL, there was always someone listening and understanding online, which is what Elyse discovered when she released A Conversation With Friends , a documentary about her year with depression, at the end of the 2016.

“It wasn’t until I the most vulnerable in my work that I was able to reach the people that I was trying to reach,” she says. “I had a tonne of girls respond to that film. They saw themselves in my story, and connected with my experience of depression and heartbreak.”

“I was at the bottom of the barrel; I had two options, really, and I chose to get help.”

Elyse responded to each girl directly. Through these interactions, she was able to learn about the kind of help they needed; some girls wanted advice on treatment, while others just wanted someone to talk to. Where possible, she referred them to local medical resources, but Elyse wanted to do more, she wanted to create something concrete that could somehow help everyone; a community where girls felt safe to talk about their struggles, where they knew they wouldn’t be alone, and most importantly where they could find information about mental health, that they otherwise might not be able to access or afford. So, in January last year she set up an Instagram page and told all the girls she’d been speaking to privately to migrate over there, which is how Sad Girls Club was born.

As the page gathered momentum, Elyse thought it would be a great idea to get all the girls based in the area together for a special event, which she hosted with New York-based therapist, Shira Burstein, in Manhattan’s women’s only club, The Wing, and livestreamed it on Facebook, where over 22,000 people tuned in to ask questions and share their own experience. Spurred on by this, Elyse created the official website, where contributors can post powerful personal essays, poetry, and art, and where girls can find out about useful information and statistics, as well as stay up to date with news of the club’s monthly workshops and events.

Exactly one year on, Elyse is still pinching herself. “It’s very surreal,” she laughs. “I’m so happy that I’m able to help guide these girls from all over the world.” As you’d might expect, most of the Sad Girls Club following is based in the US and across Europe, but as Elyse proudly tells me they’ve also got large followings in Iran and Iraq. “One of the things we’re trying to figure out is how to find girls who don’t know how to reach us, who don’t have mobile phones or Instagram.” She’s still figuring this out, though. But that’s the beauty of Sad Girls Club: just like the girls in the club, Elyse is still figuring her shit out, she’s still learning to deal with the trials and tribulations that life throws at her, just like you or me. Sure, she’s a million miles away from the beaten down shadow of herself that was two years ago, but managing her emotions is still a daily struggle. What keeps her grounded, though, is her duties with the club. Right now, she’s narrowing her focus on mental health education both in schools and the workplace. In the last few months, she’s started working with various companies in New York on creating mental health workshops, where employees can come and learn about mental health treatment and create an open dialogue about anything they might be struggling with.

With women of colour being particularly vulnerable to mental illness and the wider social stigma surrounding it (which might prevent them from wanting to seek medical help in the first place), Elyse has placed priority on helping them. According to the U.S Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, African Americans are 10 per cent more likely to experience mental-health problems than the general population, made worse by the fact that they’re also 7.3 times more likely to live in high poverty areas, which means limited access to mental-health services.

“We have a lot of black women join us who are well into their 20s. Some of them have told me that this is the first time they’ve ever spoken about depression and mental illness. It’s these women who need Sad Girls Club the most.” But why is it that women of colour are more likely to suffer in silence? “I think growing up, we don’t have examples of people who look like us with mental illness. There’s a just such a lack of black representation, and conversation. This is something that we need to change.”

Over the past few years mental health has become part of the cultural conversation in a way it’s never before, in no small part due to the internet, which has not only afforded people around the world access to a wealth of information so that people can actually identify what it is they or a loved one has been struggling with, but also it’s allowed for an open and ongoing global conversation about it. It’s become socially acceptable to talk about how shit you’re feeling.

Elyse is helping this conversation continue. “Think about your little cousin or your little sister, do you want them to live in a world where they can’t talk about their feelings or not? That’s what I always keep in the back of my mind.”

Credits

Photography Jocko Graves