From a young age, Frank Stewart learned the subtle art of travelling between cultures with an intuitive fluidity and profound sensitivity to his surroundings. Hailing from Nashville, Tennessee, during the final years of segregation, Frank moved around frequently and was always the new kid on the block. He attended nearly a dozen different grammar schools over the years and quickly became adept at navigating social hierarchies that develop during youth.

“I always had to go out and try to fit in,” he says. “Sometimes I had to fight people because there’s a pecking order when you come, and I was gonna be the boss.” Raised in Memphis, Chicago, and New York, Frank developed a keen ability to discern the regional distinctions across the intricate network of Black American communities during the second half of the Great Migration.

Frank’s instinctive mastery of circumstance proved a foundational skill in a photography career that began in 1963 at the tender age of 14, when his mother Dotty brought him to the March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs. “I grew up in the segregated South, and that was the first time I saw throngs of Black and white people together,” he remembers. “It was so impressive to me that they all came together for Black folks.”

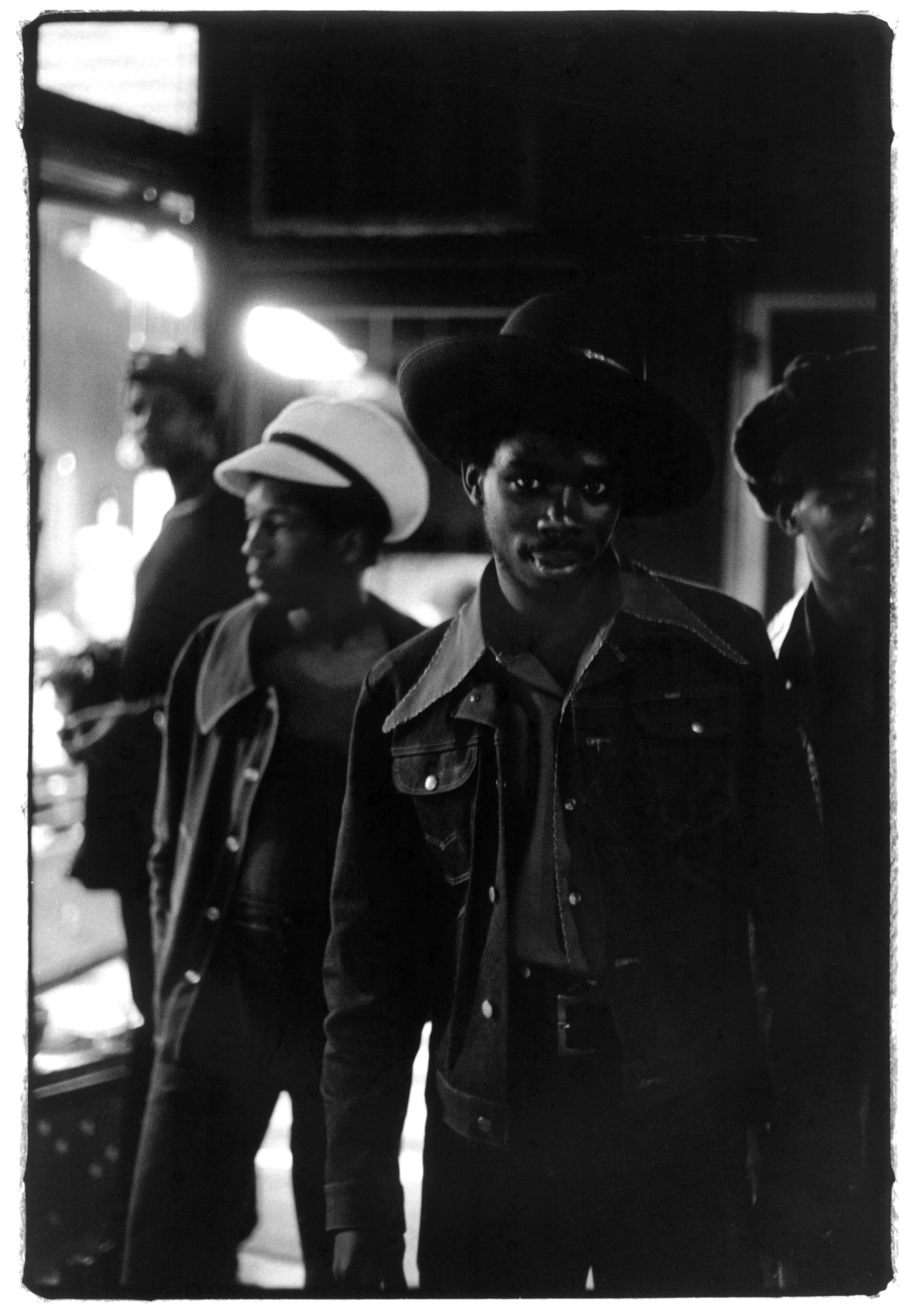

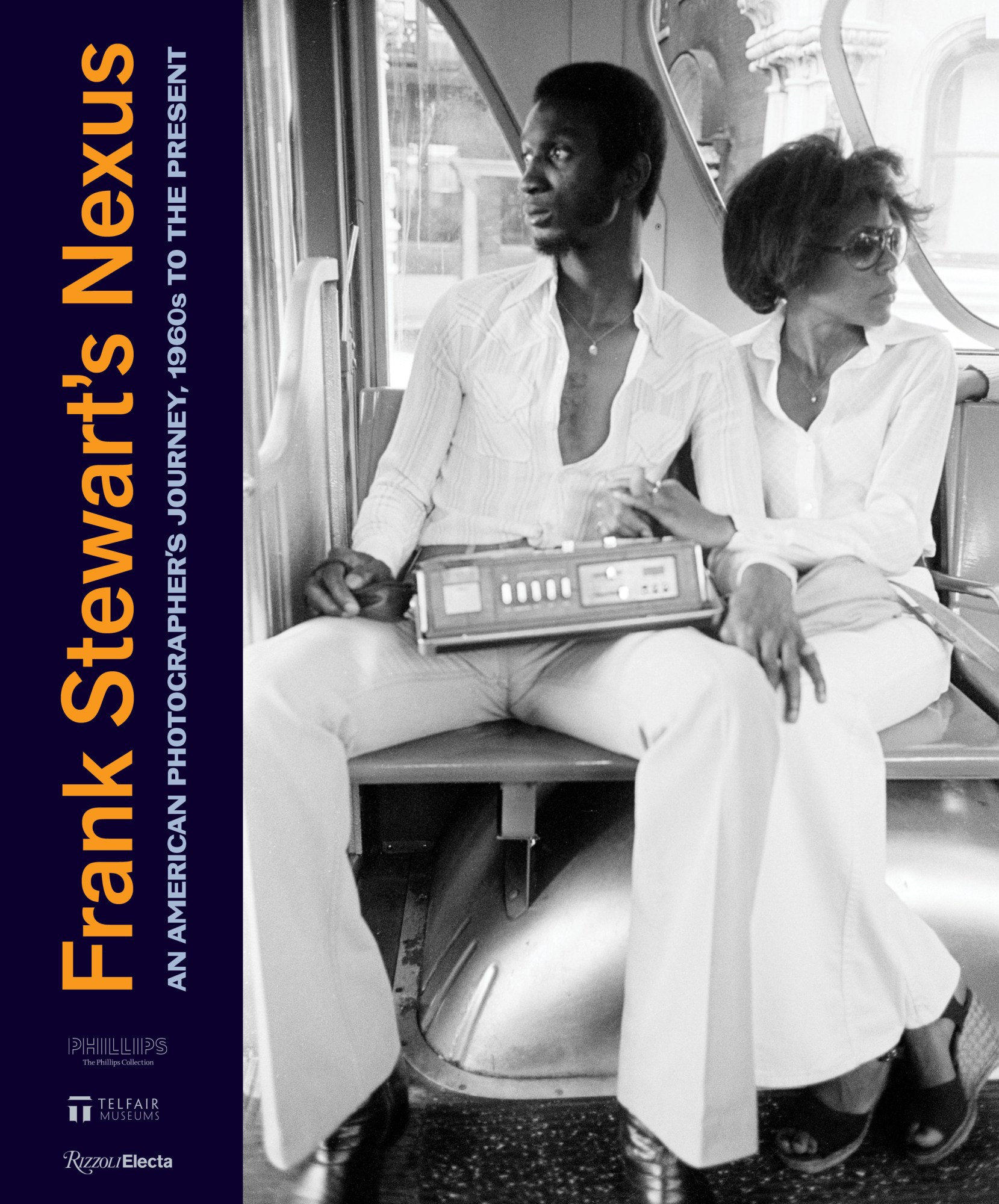

Frank borrowed Dotty’s Kodak Brownie and made his very first photographs, which marked the start of a six-decade journey around the world with camera in hand. In the new travelling exhibition and monograph, Frank Stewart’s Nexus: An American Photographer’s Journey, 1960s to the Present, he looks back at the intricate web of connections that forge profound cultural ties. Envisioned as a visual autobiography, Frank Stewart’s Nexus weaves a majestic tapestry of Black life, revealing the artistry, rituals, and expression of self that unites the diaspora across time and space.

Frank’s formative experiences shaped his ability to close the distance between strangers through the act of mutual recognition and respect. “I wouldn’t try to overpower, control, or impress anybody; I just come in, meet people, and talk to them to find out what they like and what they don’t like and not judge them by it,” he says. “I think people like that I don’t judge them, and everything becomes natural.”

After moving to New York in 1969, Frank met legendary photographer Roy DeCarava, who co-authored the groundbreaking 1955 book The Sweet Flypaper of Life with Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes. “The way Roy dealt with Black people in terms of photography, how much empathy and love he had in the imagery he produced,” Frank says. “It had a big impact on me. There were no positive images of Black people from the South. So when I saw Roy’s photos, it was like, ‘Oh, he’s a kindred spirit’, and I think he probably saw that in me too.”

In the mornings before school, Frank would visit Roy to talk about photography. Then, one day, Roy asked if he wanted to attend the Cooper Union, New York’s premier art school, where he taught. With Roy’s support and encouragement, Frank enrolled in 1971, studying photography with Joel Meyerowitz, Stephen Shore, Arnold Newman, and Tod Papageorge.

But it was a young African and pre-Colombian art professor named George Nelson Preston who would change Frank’s life, encouraging the young photographer to embark on an independent study program in West Africa in 1974. Over a period of six months, Frank travelled to Liberia, Nigeria, Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), Togo, Dahomey (now Benin), Ivory Coast, and Ghana, seeking knowledge, wisdom, and understanding that went far beyond what passed for American education as a young Black boy growing up during segregation. “African Americans had a whole, intact culture that was never talked about or written about in the history books,” Frank says. “I always wanted to know where it came from and how it was codified, so I started out in Africa.”

By the mid-70s, the African Independence Movement was in full swing, creating a cross-current across the Atlantic. Stateside, the Black Is Beautiful movement of Brooklyn-born brothers Kwame Brathwaite and Elombe Brath drew upon the teachings of Marcus Garvey, fuelling the spirit of Pan-Africanism worldwide and inspiring a generation of artists, intellectuals, and innovators to revisit the Back to Africa movement of the 20s. In the United States, collectives like AfriCOBRA and Kamoinge, which Frank later joined in 1982, centred the vision of Black artists at a time when they were largely excluded from mainstream institutions, media, and publishing.

After graduating in 1975, Frank shot stills for a film documenting Two Centuries of Black American Art, the landmark 1976 LACMA exhibition curated by David C. Driskell. There, he met and photographed leading Black artists, including Jacob Lawrence, Alma W. Thomas, and Romare Bearden, whom he remained close with until the artist’s death in 1988. “I worked with him for the last 13 years of his life, and he would break down what he was doing in the frame,” Frank remembers of his time with Romare, who reimagined the language of art and photography through collage. “Breaking up space was a thing for him, and he told me that if you take the people out of the composition, you get Mondrian. He had knowledge of everything. Guys back then like him were Renaissance men.”

At the same time, Frank was deeply immersed in the flourishing jazz scene. During the mid-50s, his mother Dotty partnered and later married jazz pianist Phineas Newborn Jr. As a child, Frank regularly visited their midtown Manhattan home, regularly accompanying Phineas to legendary clubs like Birdland, the Village Vanguard, and the Five Spot, where he met luminaries like Miles Davis, Count Basie and Roy Haynes.

In the mid-70s, Dotty introduced Frank to jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal. “He was the first one to take me on the road, and that was a mind-opening, mind-bending, mind-expanding experience,” Frank says. “He was famous, but nobody else was, so he stayed at a three-star hotel, and we would be at a hotel 30 miles outside the city. I got to see the real road.”

At the same time, Frank worked as a staff photographer for the Studio Museum in Harlem and travelled to New Orleans in 1976 as part of a folk art project. There, he met jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, who was performing with his father Ellis and brother Branford, forging a connection that would later result in a three-decade gig as senior staff photographer at New York’s prestigious Jazz at Lincoln Center.

In a majestic poem that opens the monograph, Wynton crafts verse as rich and thick as gumbo, paying tribute to Frank’s spectacular journey and giving readers a taste of the mystical blend to come in the pages ahead. “Go ’head Glorious Griot with your Leica ready set,” Wynton writes. “He line up all the angles (ain’t a gesture he don’t get).”

From the outset, Frank followed his star, seeking to understand how all these different influences across the diaspora became codified into African-American culture. Ultimately, it all goes back to the drums, which beat in rhythm with the human heart — one, two, one, two — and can never be separated from the people, no matter how far they travel from the motherland.

‘Frank Stewart’s Nexus: An American Photographer’s Journey, 1960s to the Present’ is on view at The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC through 3 September 2023; The Baker Museum, Naples, FL (14 October 2023–7 January 2024) and Telfair Museums, Savannah, GA (9 February – 12 May 2024). The catalogue is published by The Phillips Collection/RizzoliElecta/Telfair Museums.

Credits

All images courtesy of Frank Stewart