The link between Richard Curtis movies and one of the most revered producers and singer-songwriters of the past decade might not seem obvious. But, after telling James Blake that I started weeping at his recent London show, his response is to talk about the British director’s 2013 movie, About Time. “I was crying my eyes out watching it, and it was good to have that release,” he says. “I’m sure there were layers to why it made me cry, but that’s different for everyone.”

We all need that kind of catharsis from somewhere, and so, in turn, James is happy to provide it where he can. “I guess [my work] is me having some kind of emotion and trying to distil it into music, and then it coming out the other side and giving someone that reaction…” he says. “That’s the point: I want people to be able to work through their own thing that they’re going through, or even just giving them a release.”

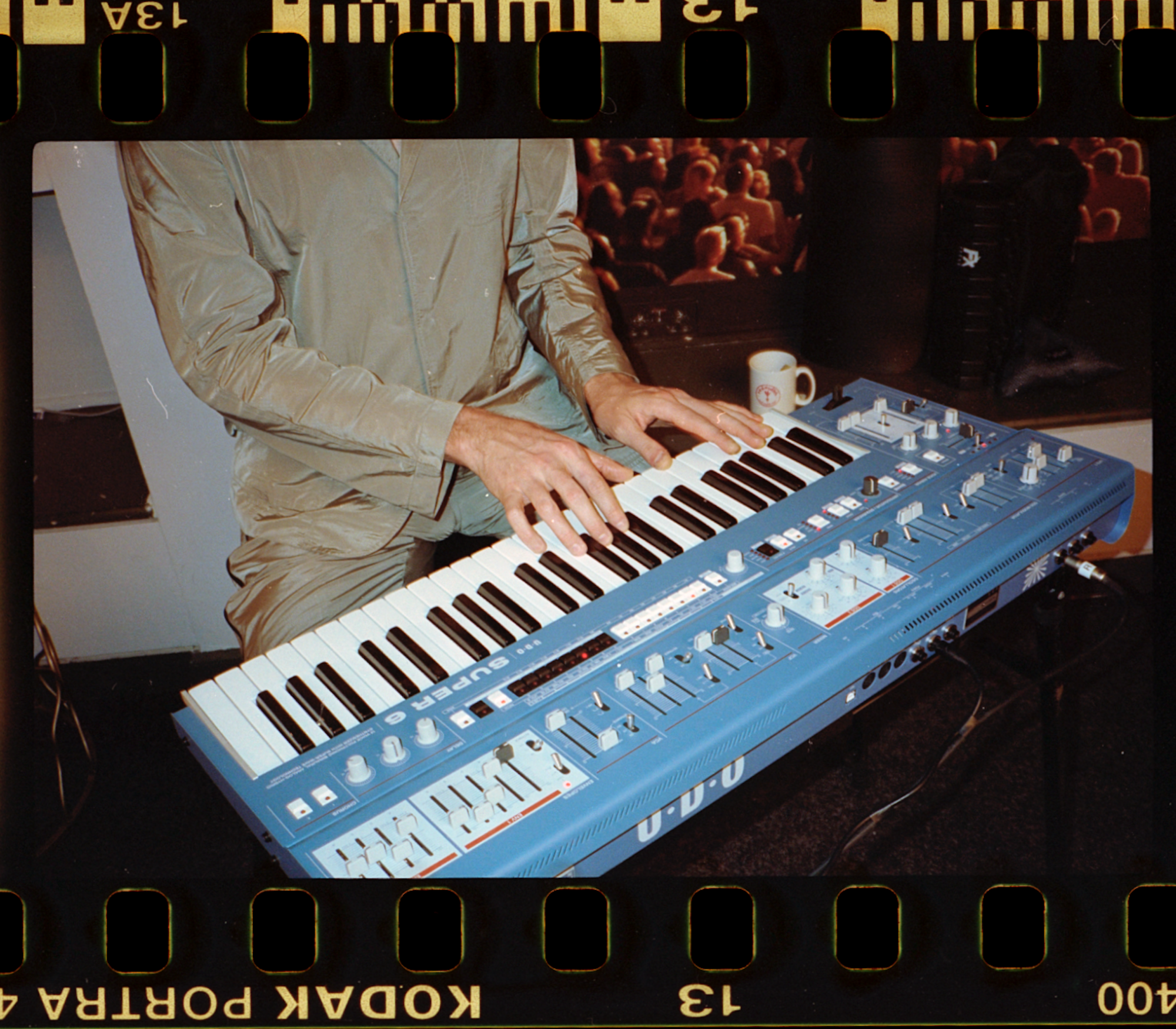

It’s a few days after that sold-out headline gig at Alexandra Palace when we talk. The 33-year-old artist is sitting in his London hotel room eating crisps, pensive and unassuming. He’s dressed in a bright green Lazy Oaf co-ord – he loves fashion as a way of expressing himself, he explains, wearing custom Dior for much of the recent Europe tour (“On stage I like to feel a certain way – I quite like long, flowing stuff”). Normally based in LA, he’s having a good time back in his hometown, decompressing from tour, seeing friends and family, walking the beloved dog Barold he and his partner Jameela Jamil share. But this is not all joy when living out of a hotel, he concedes with laughter: “A dog’s usual toilet regimen isn’t quite possible and there was… an incident and it was… very bad”.

The conversation is laced with funny asides like this, or self-effacing moments. We discuss his proclivity for stunning covers of songs; he quips: “It’s an amazing way of not having to write anything; maximum reward for minimum effort.”

In spite of his easy humour, James is often perceived as being ‘serious’ and ‘sad’ for singing honestly about his feelings – a belittling of men’s mental health that he addressed in a 2018 statement on social media and again in an essay in 2019, ‘How can I complain?’. “I’m aware of the perceptions that people might have of me,” he says, “but I think the point is that it doesn’t matter, and I actually don’t care anymore – and I think that is good for both me and my listeners.” He paraphrases Georgia O’Keeffe as he continues: “There’s criticism and there’s praise, and they both need to go down the same drain. I think coming into your early 30s, you hopefully start to feel more comfortable in who you are.”

It’s something you can hear on his most recent album, 2021’s Friends That Break Your Heart, a record that addresses relevance in a society obsessed with youth. Although he’s known for his work with some of the biggest, most celebrated artists in the world (Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar, Travis Scott), collaborating with UK rap behemoth Dave, and potentially, according to James, popstar du jour PinkPantheress, he insists he’s not especially interested in chasing relevance. “Relevance is not hugely important to someone like me. Anytime I’ve been aware of it or thought about it too much is when I’ve had my fingers burnt.”

Revisiting the music of Friends That Break Your Heart in a live context has been an intense and visceral experience. There are songs about past experiences, of drifting from loved ones, that he’s processing all over again. “Some of those songs are quite raw,” he says, “I’m daunted to play [them] because they almost take me back to the moment I wrote them and how I felt then, and I find it quite difficult. That’s probably a side of songwriting that isn’t talked about a lot – how hard it can be to go back and sing some of these things. As cathartic as they were to write, sometimes they become inescapable, immortalised fragments of your past.”

The record is also as close as James – who is probably still best known for his uniquely interior but vast, somewhat off-kilter productions and silky, intimate, quaking vocals – has ever gotten to traditional pop songwriting. “I was trying to perfect something on that album – the essence of classic songwriting, trying to make every lyric count, creating something that would be meaningful the whole way through,” he says, “And the rest of the album is what it is, but ‘Say What You Will’ is the pinnacle of my version of that kind of songwriting. Once I did that I was like, ‘I’m good, I don’t need to write any more songs’.”

Whatever will follow it is “more whimsical,” he admits. “It’s less focused on trying to get those messages across. It’s a bit more esoteric, probably more playful.”

This interest in future projects rather than sitting in the present is habitual, James says, though it’s at odds with how he’s trying to be these days. “The real joy is in the work itself, the people around you that you love, the sharing and laughing and being creative – moment to moment presence and joy,” he says, “You can plan and make time for those moments, but you can’t plan for how you feel when the achievement ends up feeling empty.

“I’m someone who can easily become anxious about shit in the future, about what I don’t have, what I’m not achieving – and I think the remedy to that for me was achieving some of those things and going, ‘Oh, I didn’t feel anything when I put that album out’ – I thought the adulation would make me feel something but it didn’t, and it never has.”

So he’s been trying to reframe things in his head: “Actually, what am I here to do? Is there something that really lights me up? For me, that’s the music, but also surrounding myself with people who make me tick, who really make me laugh, who I’m excited by, who make you feel like you’re in the right place.”

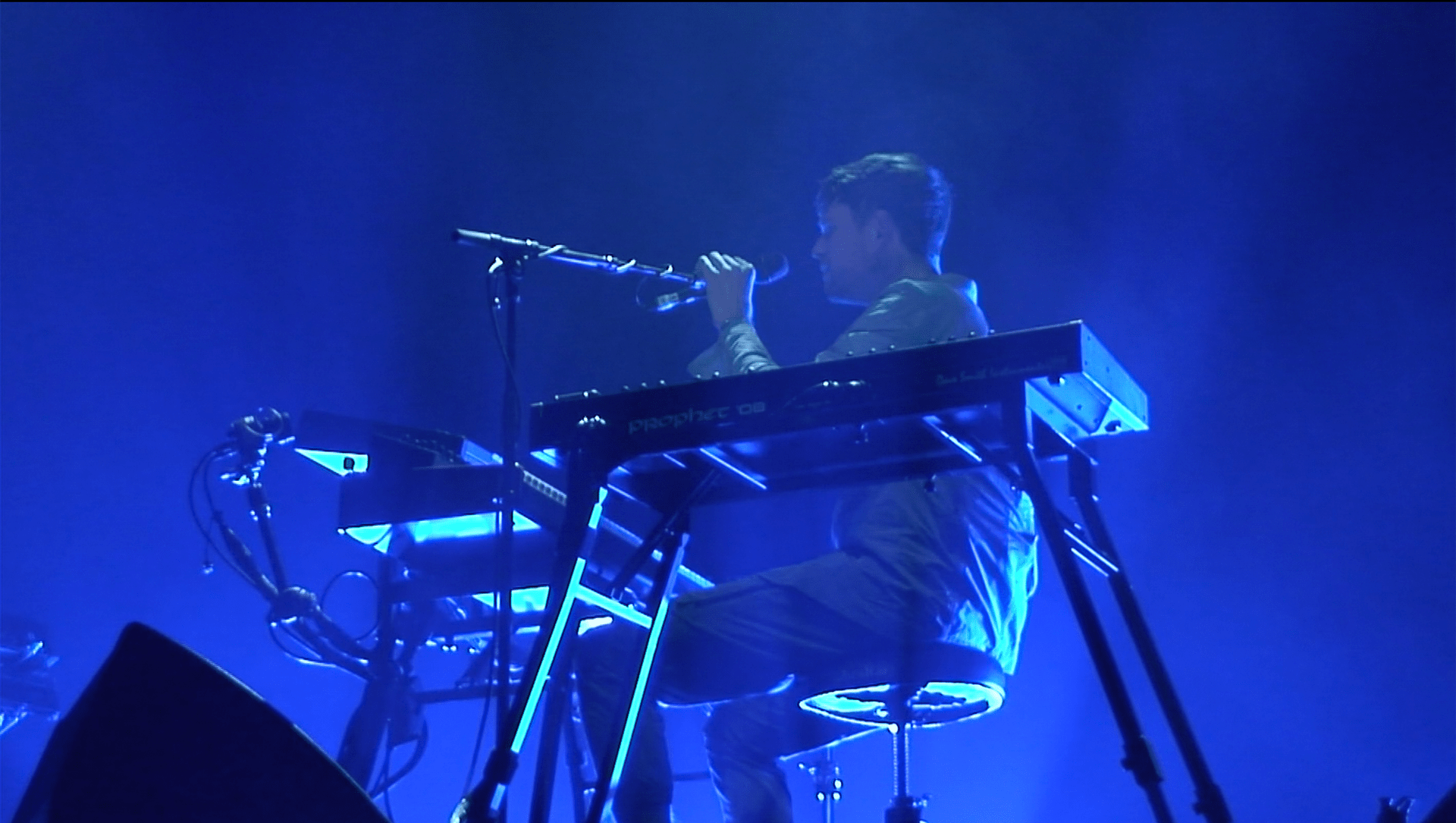

For now, James is still trying to take a moment to sit with the career highlight of 10,000 people singing his words back to him at a venue where he spent his teen years with his school friends turned bandmates, Rob McAndrews and Ben Assiter. “I literally had my first kiss at Ally Pally, there were so many formative moments there,” he says, understandably still a little overwhelmed, “Rob said afterwards it was like the end credits to a movie. Except it felt like the beginning of something too: a new era–,” he pauses, suddenly self-aware: “Which sounds like big talk, but that’s just how it felt.”

This sense of a new era might be rooted in Jakes getting older, and his shifting priorities. In the spirit of About Time – a film that’s essentially a romcom with time travel – I ask what he would say if he could go back and meet his younger self, hanging out at Ally Pally 20 years ago. “I would probably say, ‘It would serve you to stop being so self-critical’,” he says after a long pause, “Because it will stop you going forward.”

Then again, even he couldn’t have predicted this. “I knew I was trying to escape something back then, but I couldn’t tell where I was trying to escape to.” It’s definitely some kind of movie end credits moment, then: James Blake found home, acceptance and catharsis on-stage, in the very place he was trying to run from.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on music.

Credits

Photography Richard Dowker