“I always try to have my work reflect the atmosphere and energy I receive from the people and the places I am surrounded by, in the most honest possible way. Donbas was not an exception. I dove in to photograph a dystopian place stuck with an endless conflict and make a record of it.”

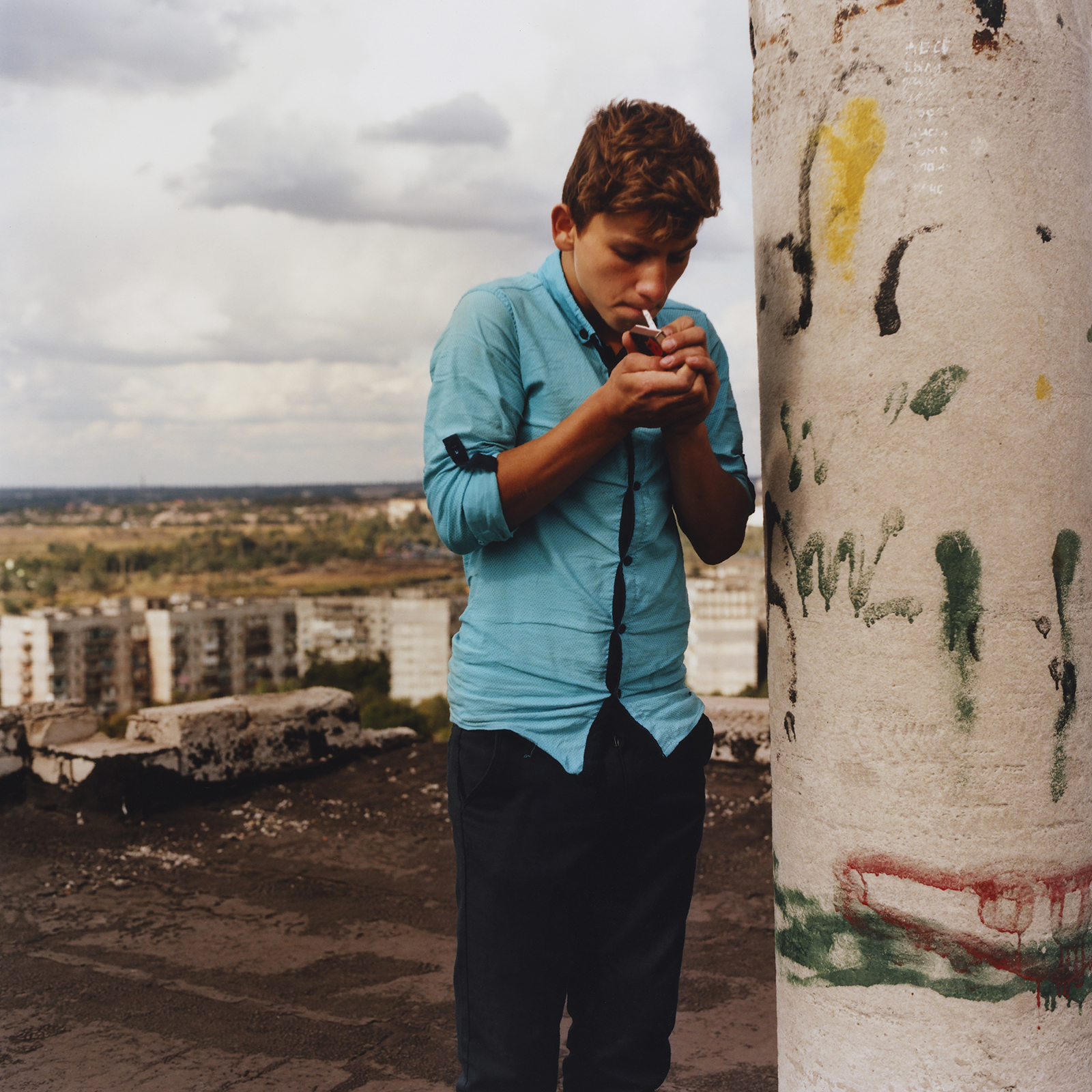

If JJ Lorenzo had to pick just one image to save from The European Forgotten Conflict — his newly-published series shot in south-eastern Ukraine in 2019 — he’d choose the one that opens this piece: of four teenage boys standing on the roof of a tall building. “That moment on the rooftop was magical,” he says. “My friend Kolia wanted to show me an abandoned Soviet housing block on his day off, but we didn’t know how to get inside. We met this group of teens hanging out outside, and they showed us how to climb to the rooftop.” To him, this interaction exemplifies the attitude of Ukrainian youth: “friendly, kind and open to meeting new people.”

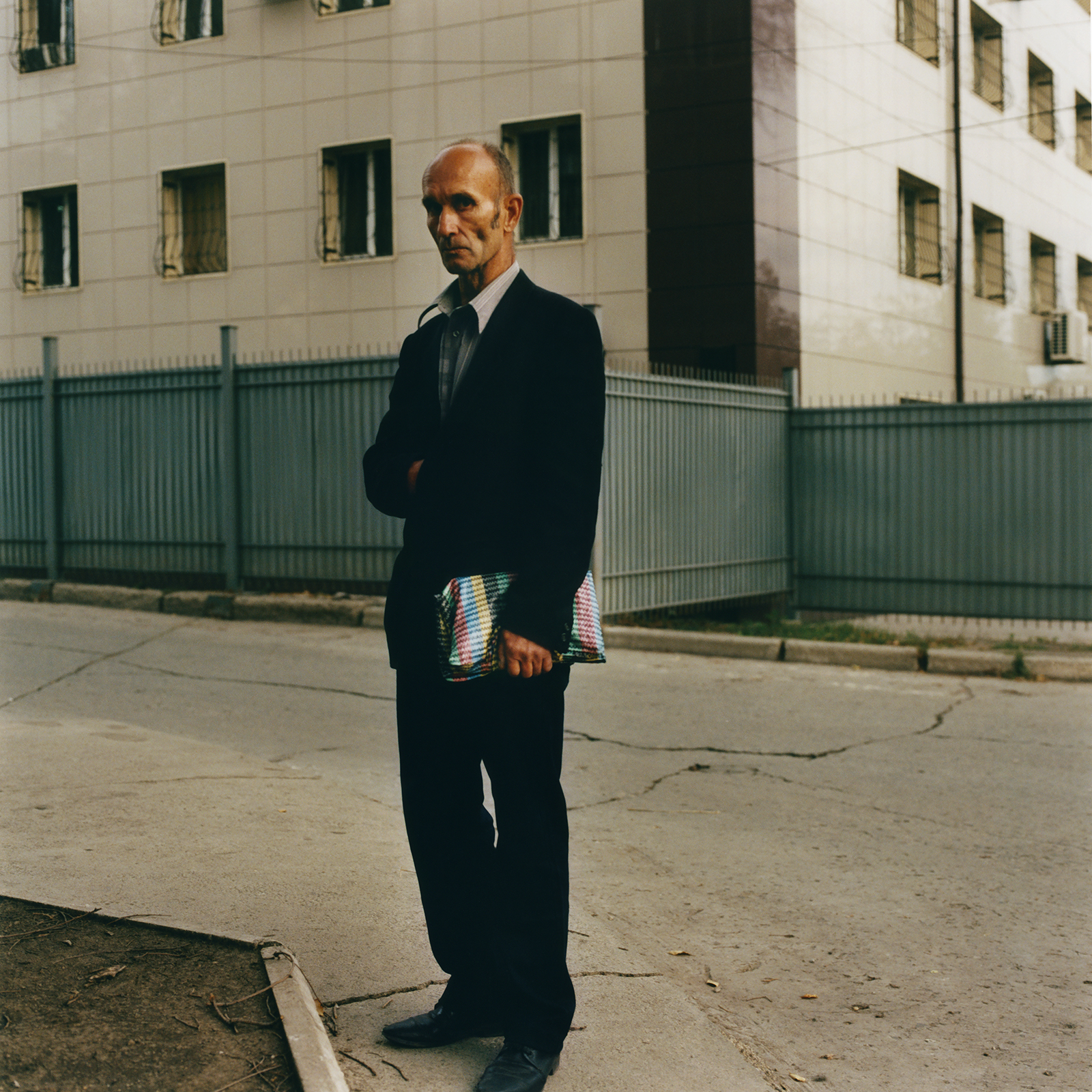

In his work, JJ looks for boundaries and “the friction they provoke”, something immediately clear in these images. Shot over a few weeks, his trip to the south east was the conclusion of a journey around Ukraine for his ongoing series Borderland, which began in 2018. By Autumn 2019, he reached the Donbas region, best known for its mining and steel industries and a population of mostly Russian speakers. “It has stronger ties with Russia, which sets them apart from western Ukraine,” he says.

The violent conflict between the two countries began in 2014 after Ukraine, a former Soviet state, began approaching the European Union. Despite a supposed cease-fire being agreed last year, as of the past few weeks, the conflict has worsened, after four Ukrainian soldiers were killed by Russian forces in Donbas. Now, Russia’s next move could decide the future of the region and the entire country.

JJ himself is originally from Spain and moved to London around nine years ago to develop his career as a photographer. But he’s stayed in touch with friends in the region, who describe to him the current heightened sense of danger. “They are more worried than usual because of the Russian troops on the border,” JJ says. “People are observing crowds of soldiers and a huge number of tanks and big weapons; even small villages have this military presence.”

His photos may not capture the army and their guns, but they do seek to translate an atmosphere of flux and the sinister consequences of geo-political instability. “Far-right groups arose in Ukraine since 2014, and even though they are a minority, their sinister presence cannot be ignored. One of those groups is Azov Battalion which is based in Mariupol,” he says, a city where many of these images were shot. “They have been linked with white supremacist and anti-LGBT ideology. Young people are an easy target for them: they approach them by inviting them to sports events or summer camps, seducing them with a romanticist idea of the motherland and a wide array of hate.”

Before starting, JJ asked himself, what might it mean to be born and grow up in Donbas in the years after the collapse of the Soviet Union? “Life is more complex for young people than for the rest of the youth in the country, he says. “They have [become] used to living with a permanent conflict, and the memories of how it was before 2014 seem like a forgotten dream.” Cities like Mariupol are filled with young people looking for jobs in the army or the steel industry, while “those who are lucky and have a better financial situation try to move to Kyiv, Kharkiv or even abroad to places like Poland.”

Overall, by presenting this series now, the photographer wants to draw the attention “of as many people as possible” to the plight of Ukrainians, to remind them “that there is a war going on in Europe and that it’s not as far away from home as we think. Aside from geo-political gambling, people’s lives are affected drastically by this endless conflict.”

Credits

All images courtesy JJ Lorenzo