In 2021, photographer and writer Johny Pitts — presenter for Open Book on BBC Radio 4 and author of Afropean: Notes from Black Europe — departed from London and drove clockwise along the British Coast with the intention of answering the question, “What is Black Britain?”. Johny and his collaborator, the Trinidad-born London-based poet Roger Robinson, cataloged their journey in the book Home Is Not A Place, which encapsulates their reflections on and encounters with contemporary Black British culture. The work is also presented as an exhibition in Sheffield — Pitts’ hometown — at Graves Gallery (open until December 24), which will migrate to Stills Gallery in Edinburgh in spring 2023.

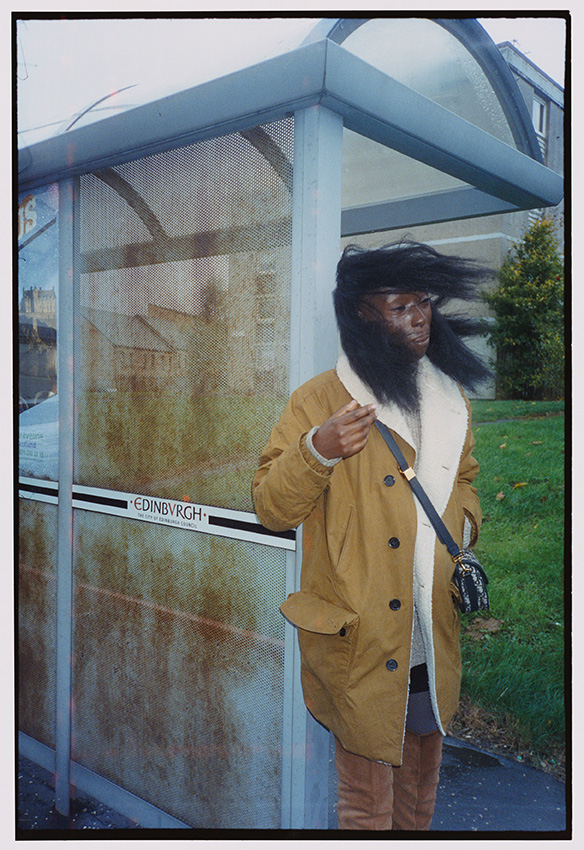

The result is a mix of portraits, contact sheets, distortions, reflections, and unselfconscious visual flaws; paired with texts by Roger, who highlights the agony of oppression (“we can’t tell / the sung from the screamed”) and the beauty of regeneration (“what is ritual without renewed vision?”). Both were eager to chronicle “Black life outside of any news cycle or on-trend hashtag”. In the text, Roger cites the Zulu concept of “Ubuntu,” namely that: “a person is a person only through other people”. The work conveys this sense of what is shared through community, thus offering a portrait of Britain — backgrounded by brick walls and hair salons, shadows and raindrops — for many who are otherwise excluded.

We spoke to Johny from his Peckham studio to discuss the way music infiltrates his photographic practice, the value of championing the ordinary Black experience, and the surprises that surface when pruning one’s own archive.

Let’s start with your “B-side aesthetic” theory, which is about choosing the creative alternative over the predictable option.

The B-side really comes from music. You would have an A-side release that conformed to the radio standards of the mainstream; then, on the B-side, you’d have either a remix or the extended ‘weirder’ version where the artist was allowed to really produce what they wanted to. This idea really suited me as I was putting together this body of work.

What I feel sometimes happens with Black images is there’s an insecurity, so we have to see Black people either as superlative — excelling in their Sunday best — or at protests or in ghettos. Instead, I wanted to create a kind of everydayness. The B-side idea emerges from thinking, Well, what is beautiful? I wouldn’t swap places with Prince Harry, David Beckham or whoever is considered on the A-side of Britain. I’m really happy about where I came from: there was real beauty, but it didn’t adhere to this notion of beauty often extolled in magazines. I wanted to create a different framework that could honour the kind of beauty that I saw where I grew up when it’s not being honoured elsewhere.

Who were your influences on this project — or who helped shape your vision of this beauty?

There are a few convergent traditions. I’ve got this book by Stanley Greene, an African-American photographer who spent many years living in Paris, and who was behind Noor Images. In the book, he said he wanted to take part in a tradition laid out by Roy DeCarava, which is “photography at the edge of failure”. I love this idea. Roy DeCarava did that a lot in his images — playing in the low end, in the shadows, in the blur. In some ways, it’s like the Jun’ichirō Tanizaki idea: that Japanese aesthetic of ‘praise of shadows’.

Another photographer who has massively influenced me is Eddie Otchere. He shot a lot of great hip-hop artists and drum & bass artists in the 90s, when they came over from the States to the UK.

Here, you mixed older work with new work. Can you talk us through how you create a visual rhythm with these different series?

I’m from a musical background; I was a music journalist and took a lot of photographs. If you think of Roy DeCarava and the project he did with Langston Hughes, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, it has jazz music encoded into the rhythm of that book through the black-and-white images of the Black community in Harlem.

If you go to a jazz gig now, it’s not really the music of the Black community. We went towards dub — Roger is a dub poet — and also hip-hop, particularly the Soulquarians like Erykah Badu, Questlove, Mos Def, Talib Kweli, Lauryn Hill, Q-Tip, and keyboardist James Poyser. You had these artists come together and work on each other’s albums: Common’s Like Water for Chocolate, Erykah Badu’s Mama’s Gun, and D’Angelo’s Voodoo. What’s interesting about those albums is that they were playing with this offbeat rhythm. The drums sample the way hip hop musicians, like J Dilla, would use a piece of music that contained real drums, and then program drums on a drum machine. But the syncopation of the drum machine would never match up perfectly with the live drums. So there’s always a slightly delayed rhythm. I was thinking: that’s what this body of work needs. It needs that strangeness, to reflect the Black experience in the West.

In terms of representation, were you drawn to certain people as you were circulating the country? I noticed quite a few uniforms, for example.

On the one hand, I’m trying to tell this very organic story of the Black experience, but every so often I try to subvert nationalist clichés and logos. I really got that from Gordon Parks with his American Gothic series, where there are these photographs of members of the Black community who are clearly struggling, pictured with the stars and stripes in the background. It sort of hints at the failures of the American dream, or how it doesn’t fit everybody. I wanted to play around with notions of monarchy, because we’re in a kingdom, which is still bonkers to me. I wanted to show Black people taking part in this country, even within these nationalistic ways: like a London guard, or a policeman. That juxtaposition was important for me. It’s like, Oh, wow, that’s so England — but it’s also somebody who’s Black. Those two things don’t have to be separate.

There are keywords or backdrops that, overtly or implicitly, relay additional messages. Is that an element that you were wilfully playing with, or do these spring up after?

I think wilful, to an extent. For the most part, when I’m out there, I don’t know what I’m doing: I’m just sensing something and working with the atmosphere. But for those kinds of images, I see the layers of meaning in a Black London guard. Having said that, you never know how things are going to land when you create a double-page spread.

At Glastonbury — after I saw a Black comedian talk about why we don’t see Black men at festivals — I took a photograph of my friend, foregrounded by a guy wearing a Nigerian football shirt; above it is the word ‘Babylon’. That was the most recent image from the whole series, and I slid it in at the last moment. Next to that is the oldest image in the entire collection, this musician and thinker wearing a T-shirt with a Union Jack that’s in Pan-African colors. So the discussion between the two images is really interesting, and I couldn’t have planned for that. Suddenly, the sum was bigger than its parts.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

It’s funny: I was looking just now at some of the images of Queen Elizabeth — because obviously, her image has been everywhere for 70 years in this country — and now that she’s passed away… As history happens, there are images that suddenly have a new resonance. This is a book about Black Britain, but maybe it could be described as a book about the end of the second Elizabethan era: the last queen to really have an empire.

It is also a book about class and the North-South divide and the state of this country. When you go north, when you come outside of the London echo chamber, so much of the country is a carcass: the high streets are dead, the clubs have gone. You go somewhere like Hull, or even Newcastle, and it’s just like: Oxfam next to Poundland next to a betting shop. It’s really depressing.

Is it worse now, though…? These socioeconomic depressions happen in cycles over time. We always think, in our own era, that we’re experiencing it the most severely. Does 2022 seem unprecedented?

There’s a lyric in that Black Star album I mentioned where Talib Kweli says: the most important time in history is the present. On the one hand, I agree with you: comparatively speaking, humanity has always gone through these huge upheavals. But we’re going through a looming recession, war in Ukraine, Brexit; we’re still dealing with the ramifications of Trump, Coronavirus, and when you speak to anybody who works with AI, they’re all terrified. I definitely think that we’re on the verge of something. Maybe it’s not the biggest change in history, but if you look at Gen Z, what they’re inheriting, I think there is a real break there. And then, of course, climate change.

How can one highlight these terrifying, shake-you-to-your-core issues, but also create a feeling of community or refuge? Can a project effectively contain both?

It’s a question I’ve been thinking about a lot. There are a number of traditions, especially from the Black community, where there’s a level of trauma, but also a sort of level of joy at the same time. I’m thinking of work done by the professor Robert Farris Thompson, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s favourite art scholar. He’d done a lot of research into this notion of ‘cool’, and how it goes back to ancient Liberia within Black diasporic communities. He talked about cool not as in ‘fashion cool’, but this ‘ancient cool’ that is poise under pressure. He traced it to what we can hear in Afro Cuban jazz, or we can see in the poise of civil rights leaders — the way Malcolm X or Martin Luther King or Angela Davis or Kathleen Cleaver would hold themselves. I think the Black Panther Party is a really good example of it, where there would be this cool composure even though the world was going to shit. I’m going to quote Black Star, again: navigate the treacherous and make it seem effortless. There is, in the Black tradition, this notion of a veneer of cool beneath the craziness that’s going on.

Another thing I think about is this notion by the sociologist Paul Gilroy called ‘Black vernacular culture’, where he talks about James Brown and when he screams on stage. Why is that so powerful? People are dancing to it, they are getting sweaty, and it’s funky — but they’re shaking away trauma. In that scream, it’s James Brown singing and being melodic, but encoded in that is an expression of the inexpressible. No essay could describe the pain of the Black experience in America like a James Brown scream can.

Whenever I produce a book, I always think of the utility of the book. What does it do? When people look at it, what is it achieving? And with this one, I wanted to offer a moment — for anybody, but especially for the Black community — to pause in this dream world. Melancholy without being too anxiety-inducing. I look at my favourite photo books in the afternoon with a cup of tea when I’m exhausted. That’s my humble goal for this book. I don’t think you can change the world with photography — but if you can offer a bit of respite for people struggling? That’s something.

Home Is Not A Place by Johny Pitts and Roger Robinson is available now and published by Harper Collins. The exhibition will be open at Graves Gallery in Sheffield until 24 December 2022 and Stills Gallery, Edinburgh 9 March – 10 June 2023.

The exhibition by Johny Pitts was commissioned by Photoworks for the inaugural Ampersand/Photoworks Fellowship.

Credits

All images courtesy of Photoworks.