Manchester courses through Kevin Cummins’ veins. Now synonymous with its greatest musical exports, the photographer has served as the city’s unofficial archivist for over four decades, witnessing the rise of The Smiths, The Fall and, most forensically, Joy Division in real time. Despite leaving the rainy enclave behind in 1987, he never really left. “I always retained links,” he says, smiling. “I was there last night to watch the [Manchester] City-Chelsea match.”

Dressed in a Stone Island overshirt, the badge tactfully removed, Kevin sits in the far corner of Bloomsbury’s Paul Stolper Gallery. It’s the opening of his new show and book, Archivum, and the space is filled with well-heeled collectors and subcultural aficionados, all there to view some 50-plus prints that had, until recently, been collecting dust inside a Kodak box. Now hung on the walls in clear plastic wallets, the collection forms a patchwork history of Joy Division from 1977 to 1984.

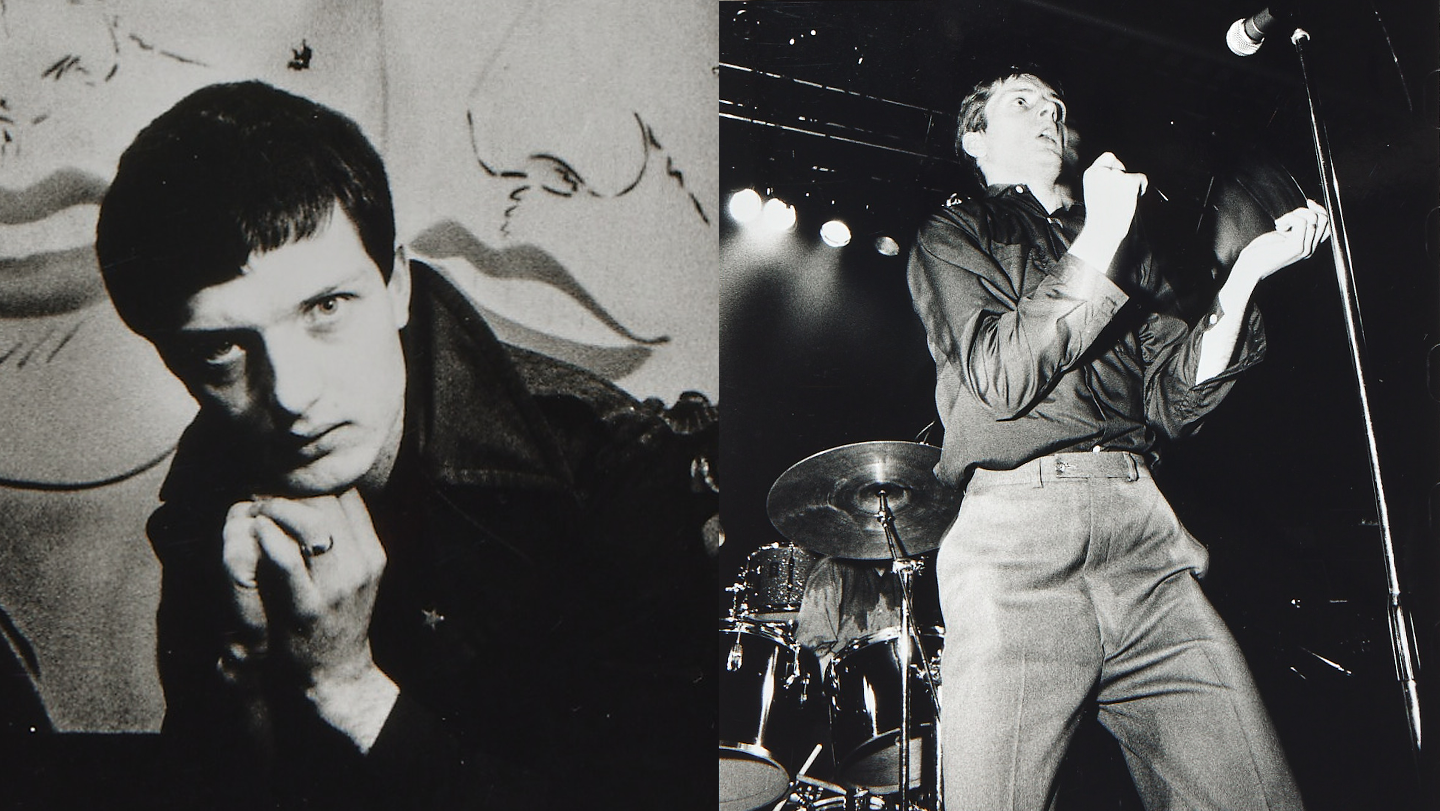

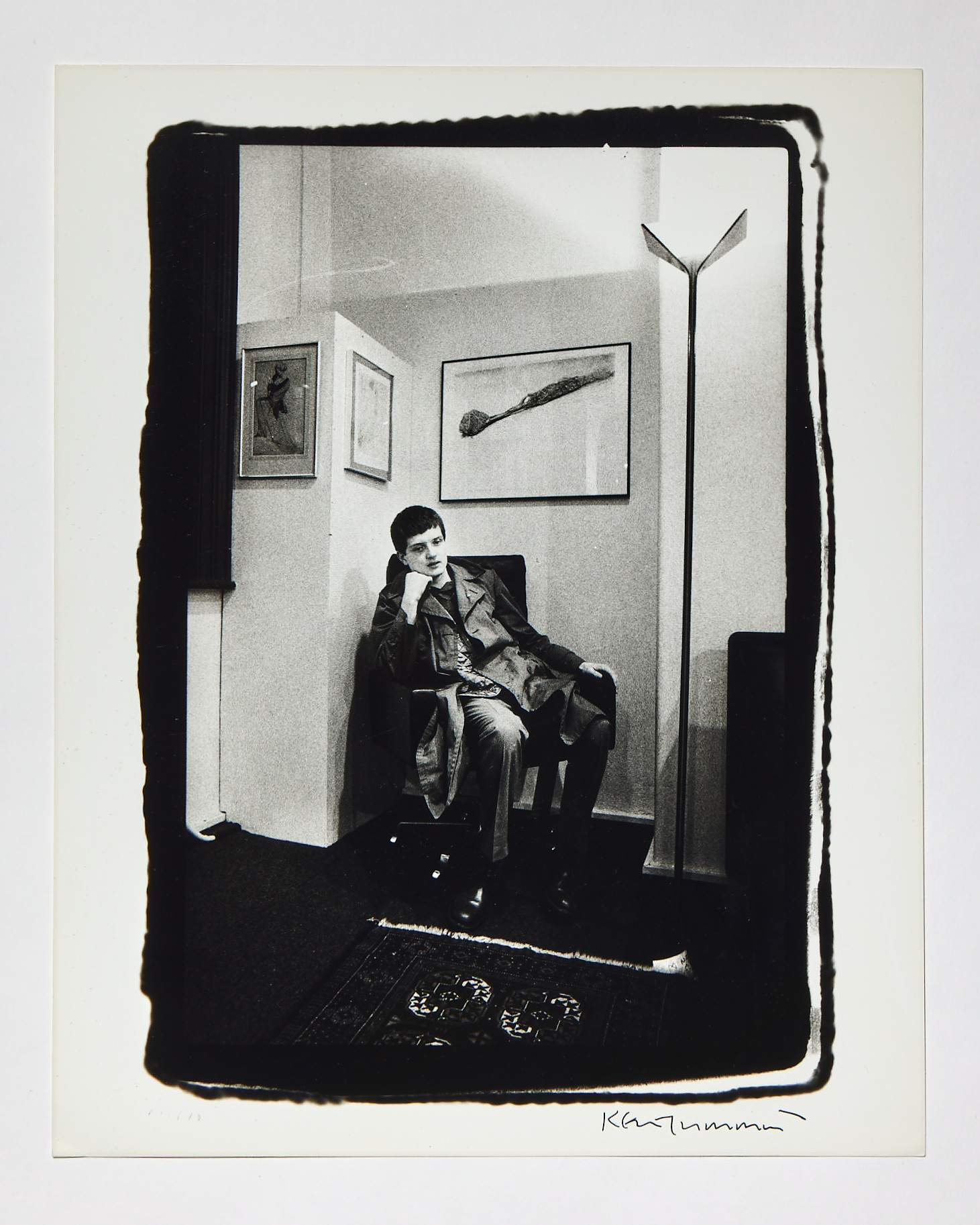

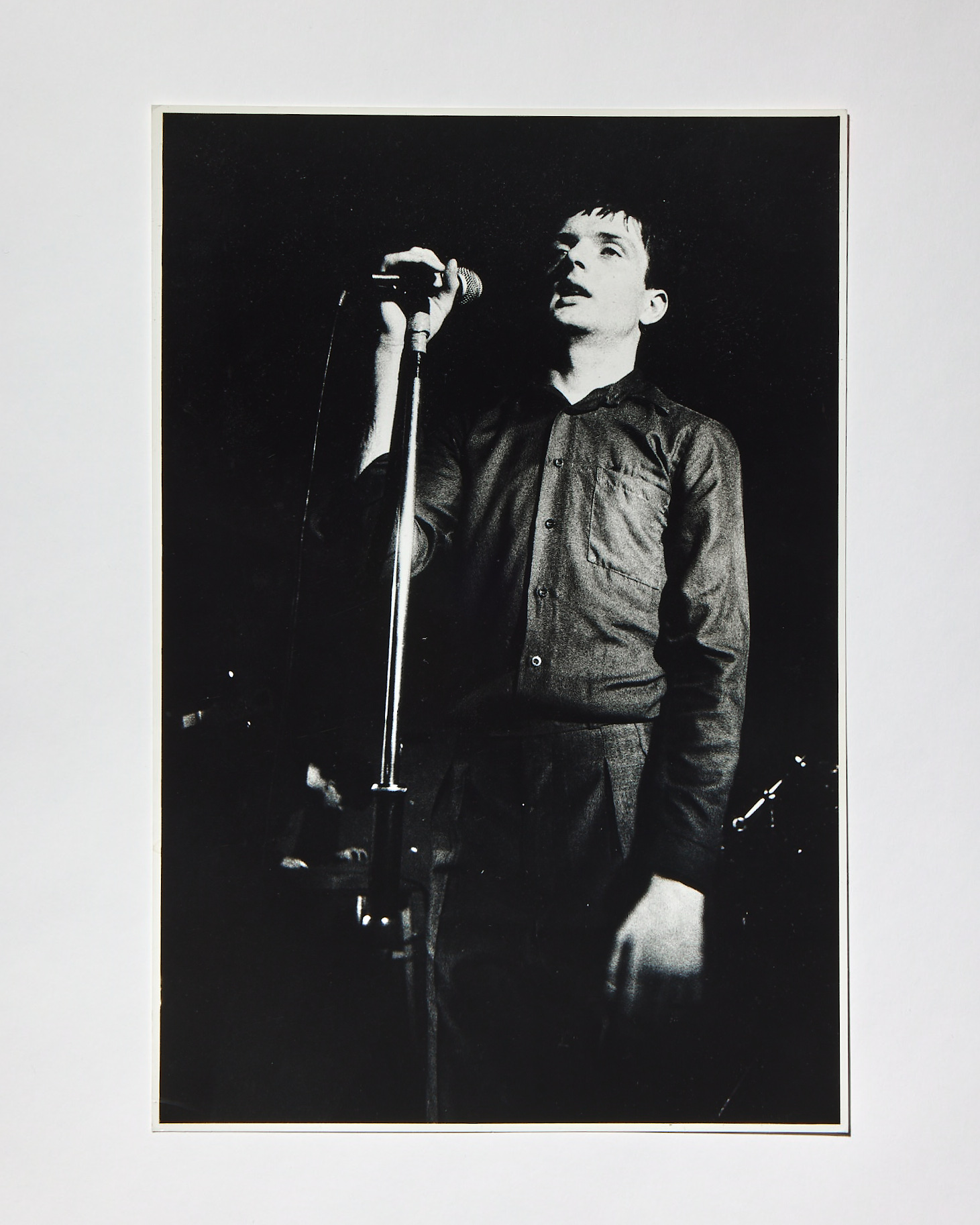

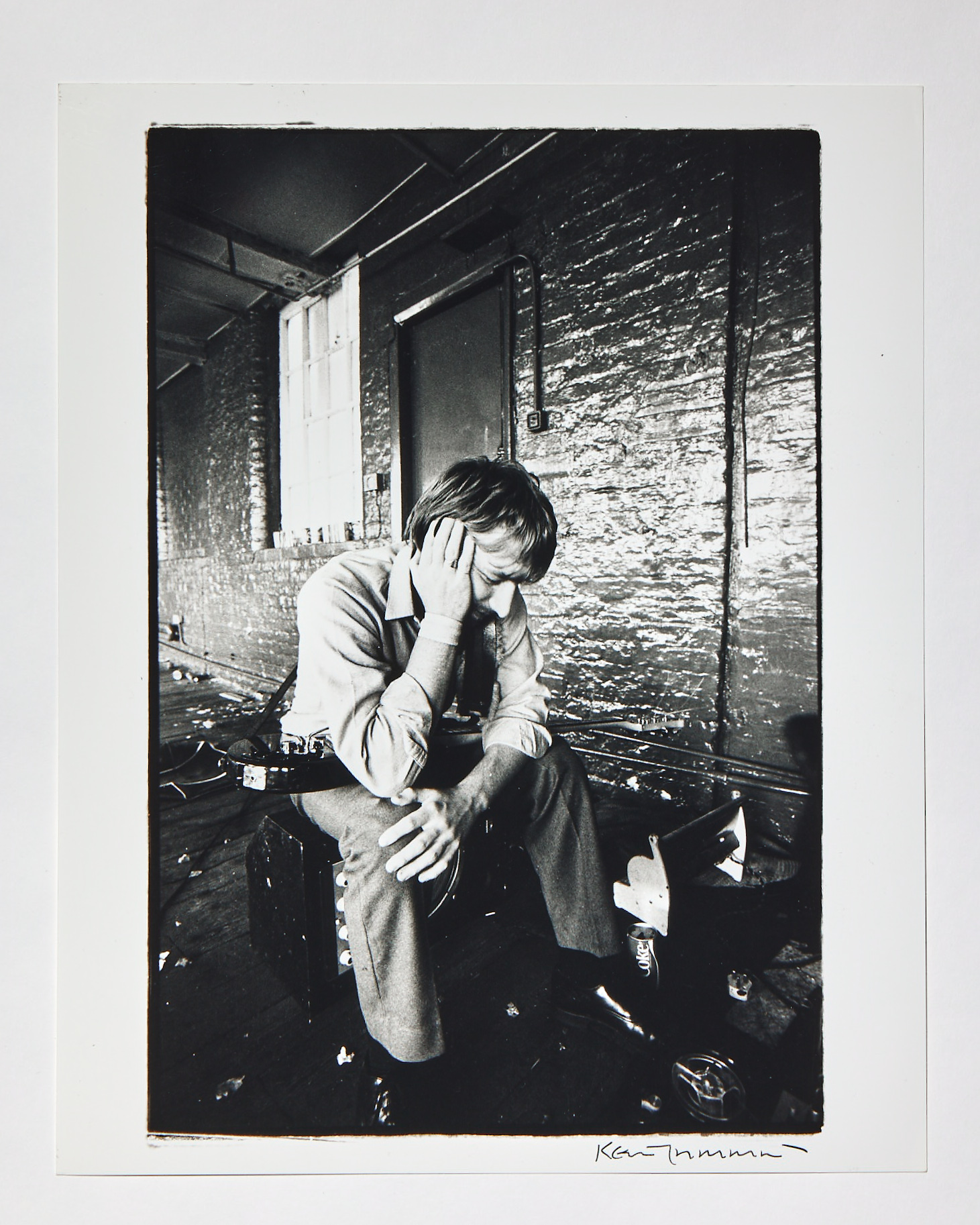

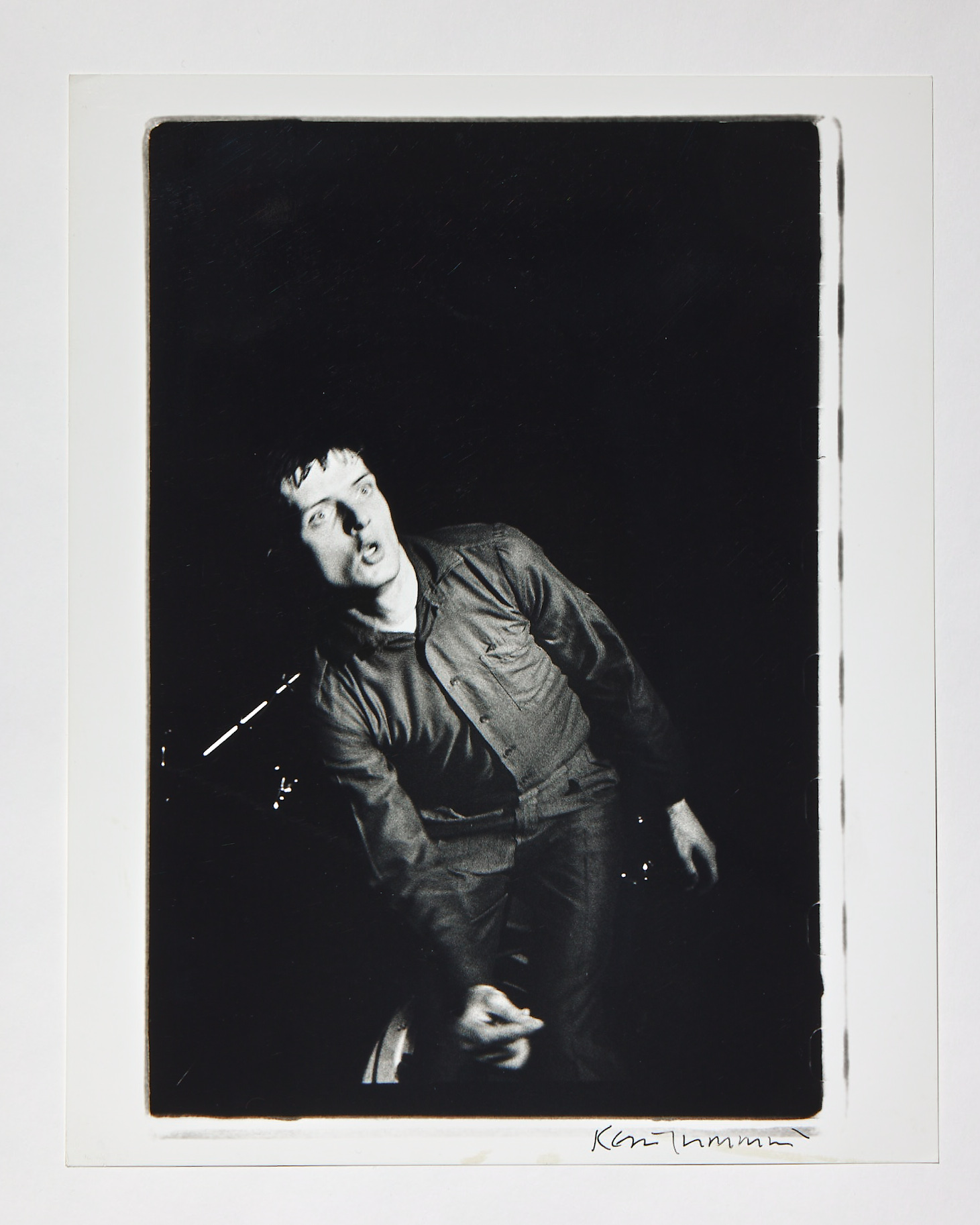

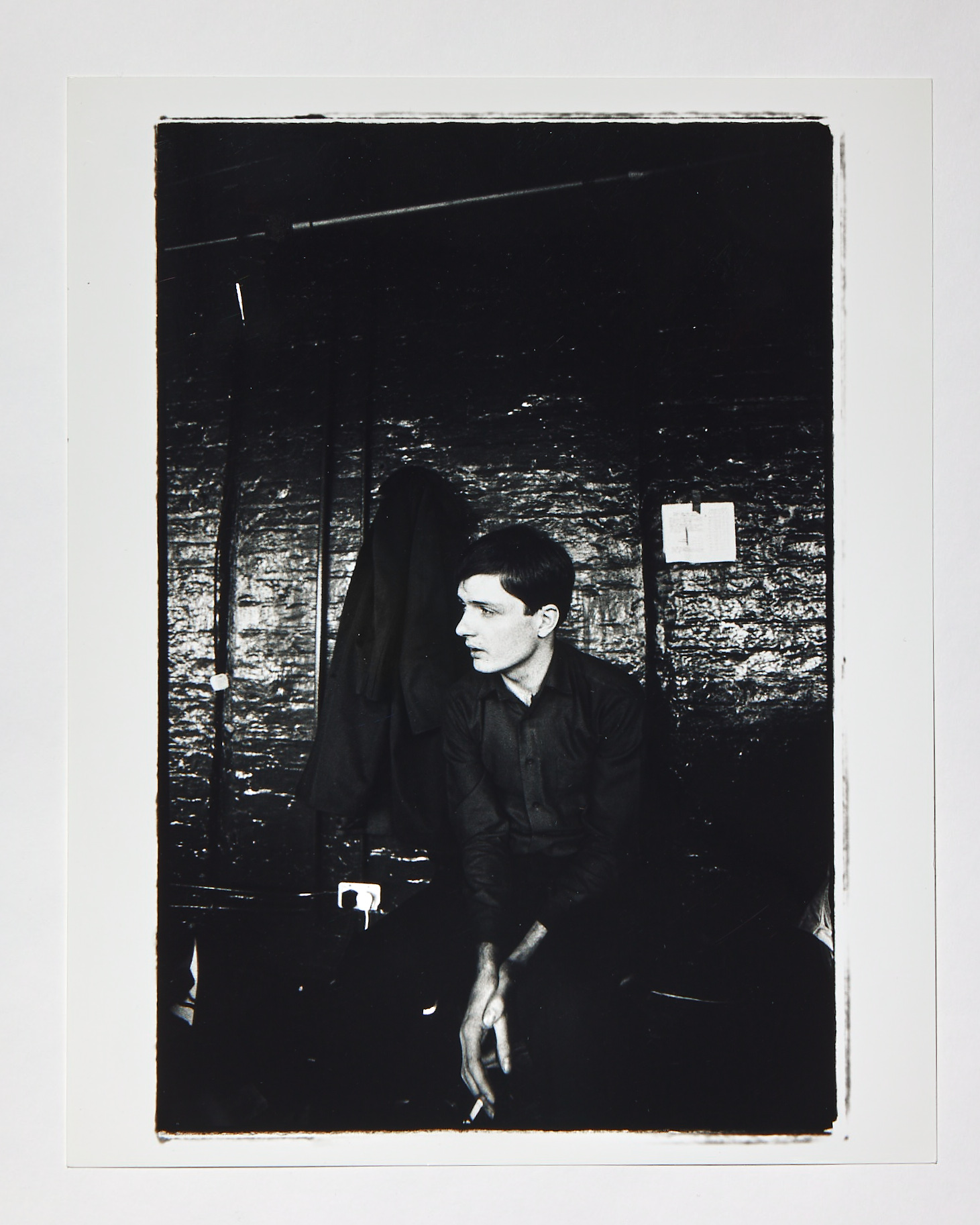

Capturing the band’s complete journey, from their original work under the name Warsaw, through to the heyday of Joy Division and, more recently, New Order, the images are categorised by gig, rehearsal or session. In one photograph, we’re welcomed into an old Mancunian haunt, Rafters, where a pale-faced Ian Curtis delivers his sonic sermon to a passionate crowd in leather chaps and brothel creepers. Next, we find ourselves in the bleak, quasi-Soviet settings of Hulme, the band posing above snowy freeways. Later, in photos taken after Ian’s death, we’re in New York’s Paradise Garage, the late frontman’s absence both obvious and poignant.

The imagery is a visual account of his entry into professional photography. Today, Kevin’s collaborators are as wide ranging as Madonna and Ice Cube, and he’s had institutional recognition in the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum, the National Gallery and Damien Hirst. These shots, though, are him at his most instinctual.

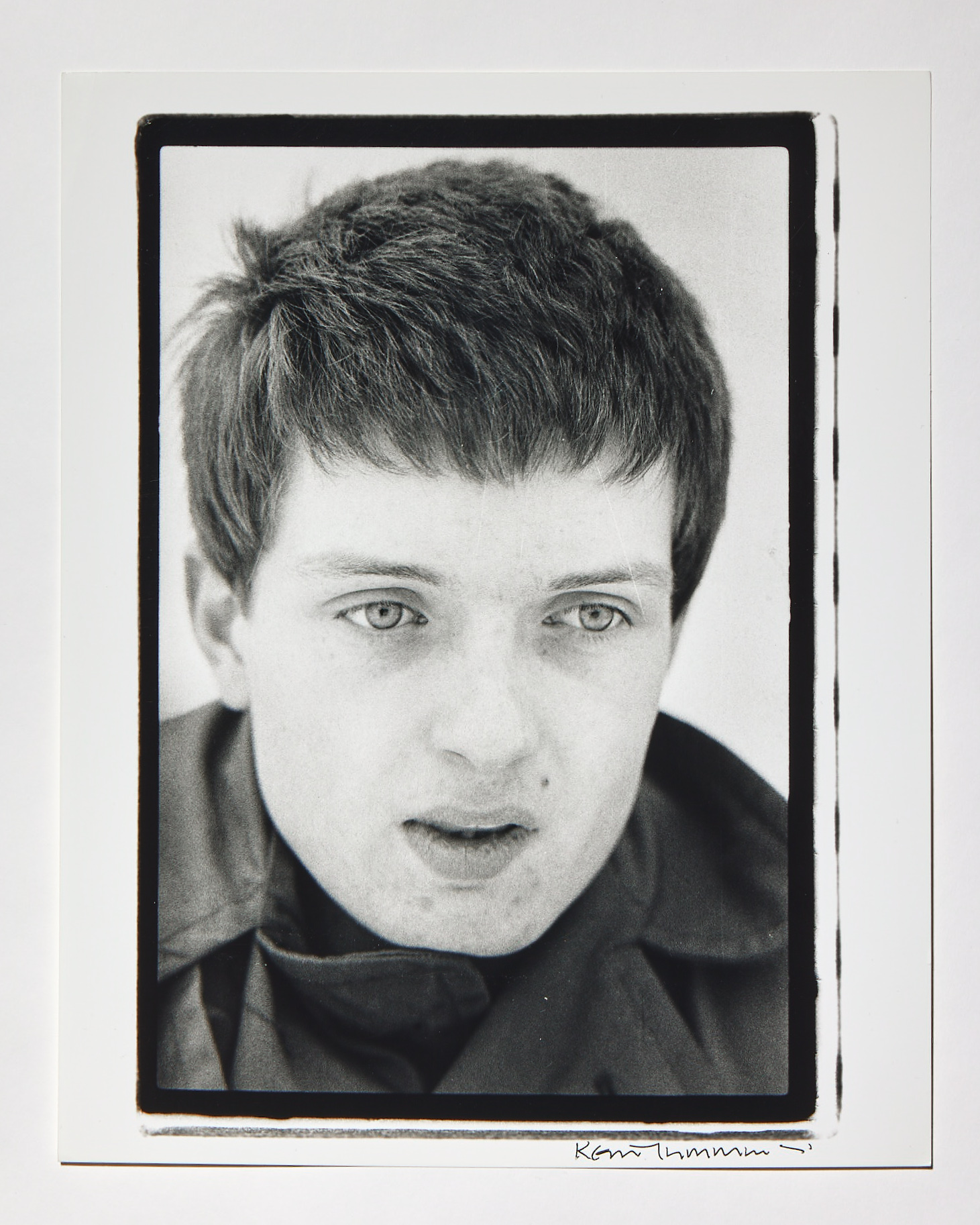

“To be known for the pictures you did while at art school and just after graduating, a certain amount of responsibility comes with that,” Kevin says. “You feel that if you’d had more experience, you might have taken the pictures in a slightly different way.” He corrects himself, though: the innocence was key. His pictures of Joy Division capture him learning to shoot a band, and the band learning to be photographed.

Poring over the work, anecdotes emerge. The photographs tell an accurate tale of what it was like to work for a weekly paper such as NME at the time, where he was regularly sent out on assignment. Whereas soft, tonal shots would simply wash out when the issue went to print, the starkly contrasted black-and-white imagery that Kevin favoured would remain impactful on the page. Wonky borders created in the dark room reveal the fledgling artist’s attempts to find a signature style of framing, while late nights developing on a shoestring budget tell the tale of a working class lad’s unrelenting desire to sanctify every shot in a half roll of film. Kevin would squeeze in extra photographs, keeping them for himself.

The costs of driving to and from gigs and ferrying photos from the North to the Big Smoke often left Kevin out of pocket. But it was worth it. Sure, the tight deadlines of a weekly left little time to philosophise on the cultural resonance of his rock photography, but he trusted his gut. “It was still seen a little bit as juvenilia,” Kevin says. “It was almost like an entry point job to then get a serious job. My parents would always say, ‘But when are you going to photograph something serious?’” Granted, Kevin would go on to appease them, shooting for the Royal Opera House, as well as ballet and theatre, but his true calling won over in the end.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

Carving out a space in British history was less his objective than an immediate wish to create strong iconography for a band he believed in. If his work could make its way onto the bedroom walls of budding fans – he also regularly shot the idolised David Bowie and was tipped off about secret Sex Pistols gigs by their manager, Malcolm McLaren – he was happy. Committed, he removed himself from the debauchery of gigs, staying sober whether he was among the punters of a Leeds University show or the unassuming dinginess of record label owner TJ Davidson’s rehearsal room. A conduit between Joy Division and the world, he advocated their brilliance before and after the people had caught on, only slightly aware that he was moving in circles made up by mavericks, including graphic designers Peter Saville and Ben Kelly, and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson.

“I always wanted them to look very cerebral, serious and intimidating,” he says of his framing of Joy Division. “The reality of a lot of those photographs is that the rest of the band were sitting behind me trying to make Ian laugh, and I couldn’t afford to take a picture of him laughing.” Never taking his exclusive intimacy with the boys for granted, Kevin reflects on his pivotal role in how they are perceived more widely, a responsibility that was emphasised further by the pre-digital era’s scant footage of Ian and his friends. He concedes that some people’s understanding of the lead singer remains skewed slightly. After all, it’s an easy – if not lazy – picture to form given his throes with epilepsy, the maudlin lyrics and a thoroughly documented divorce.

As far as Kevin is concerned, portraying Ian with grace and nuance was important, somewhere between a rock star and pensive Mancunian. “If I’d had a digital camera there, there would be pictures of him doing all sorts of terrible things and just behaving like a normal lad of his age, but that’s not what I wanted,” he says, laughing. He had his angle: “No one wants a picture of someone pissing in an ashtray. They want someone striking and beautiful.”

Kevin’s endeavour paid off. The Manchester that had drawn him in with its friendly, localised uniqueness and abundance of squats is now internationally recognised and increasingly gentrified. What he saw in the illegally occupied council properties, none-the-wiser authorities and infamously shitty weather continues to live rent-free in the minds of cultural magpies the world over. “I had an exhibition in Buenos Aires and people came up and said, ‘We love Manchester music’,” he recalls. “I said, ‘But it’s all different.’”

In his eyes, Manchester became Manchester because of its people, because of their pride in their hometown. The culture of the post-industrial city never declined. Post-punk lead on to the baggy scene, the Hacienda and the Stone Roses, and Britpop followed in their wake with Oasis – the latter bands both perennial names in Kevin’s catalogue.

Cautious of miring in nostalgia, Kevin understands his work as a form of reportage and contextualisation. Indeed, Joy Division is a loaded subject. Just as it continues to inform today’s cultural pioneers – Raf Simons, Mark Leckey and Supreme, for example – it’s also marred by a painful story of depression culminating in the lead singer’s demise. According to Kevin, it’s about legacy, not nostalgia. “I still see the band, and I still see Ian’s widow and daughter,” he says. “I don’t get upset looking at [the photos] anymore. I feel comfortable with them. And I want people to enjoy it.”

‘Archivum’ by Kevin Cummins is available to buy here. The corresponding exhibition runs until 23 December at the Paul Stolper Gallery in London.

Credits

All images courtesy of Kevin Cummins