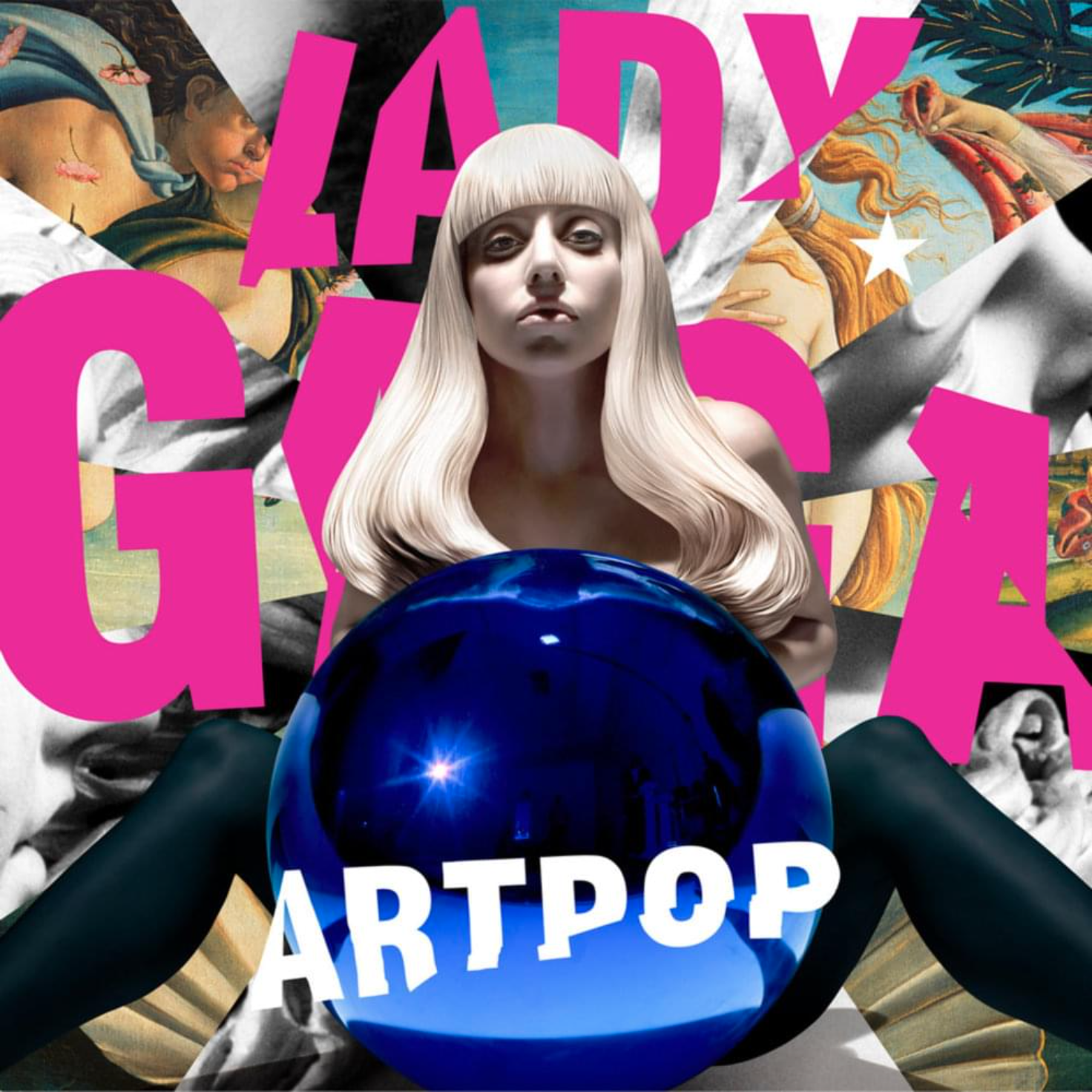

Every die-hard Little Monster will recall 2013’s ARTPOP differently. For some, it was the time the always beguiling, often challenging career of Lady Gaga entered a sparkling new era. She transported her conceptual pop framework to a place of new weirdness, making songs about Donatella, burqas and pigs, all while dressed like Botticelli’s Venus. But for others, this was the moment her career went AWOL; veering a little too deeply into the absurd. It would be fair to say this contentious lyrical left-field alienated the public alongside a contingent of her once loyal fans.

On ARTPOP, chaos was condensed into 14 erratic pop tracks that, despite being formed from the elements of mainstream chart music, threatened to derail her stratospheric ascent. The line between commercial and creative success she had flawlessly toed on The Fame, The Fame Monster and Born This Way felt jeopardised by this cacophonous meat-malleted pop album that was both unpredictable and relentless, traipsing across trap, trance and EDM. At the time, this felt like the end of Gaga’s pop dominion.

The record, executive produced by DJ White Shadow, was met with middling reviews upon its release and has been considered the low point of Lady Gaga’s career for some time. So much so that six years after its release, Gaga famously tweeted that she “didn’t remember” it. Plans for a sequel that had been in the works before the record’s release — comprising of additional songs from the ARTPOP sessions — were seemingly scrapped after the album shifted just a quarter of the copies of its predecessor.

The comparatively simple lead single “Applause”, released in the summer as a tease of the era, in retrospect feels like a bait-and-switch. It’s now tagged on at the end of a wild tracklist of songs that never settle on a cohesive sound. T.I. — he of “They wouldn’t let him into the country, poor thing!” fame — pops up on the trappy “Jewels N’ Drugs”. Then for the ultra-camp “Fashion” five songs later, Gaga — wearing what can only be described as a glittery condom — enlisted RuPaul to perform the track with her live. Nothing about the album made sense, which seemed to be Gaga’s point. After all, she did sing: “My ARTPOP could mean anything”.

But stans never forget, and those who stuck by Gaga and the record have been wondering what happened to that missing body of work she promised as a follow-up. Apparently, one reached out to DJ White Shadow personally to ask about its whereabouts. “Gotta petition Gaga on that one,” he responded. And so, that’s what fans have done: drafted a petition to get ARTPOP: Act II released that has since propelled the original record back to the top of the iTunes charts.

Moved by the gesture, Gaga has since revealed that she “fell apart” after ARTPOP’s release and the subsequent reaction it received. “We always believed it was ahead of its time,” she tweeted last week. “Years later turns out, sometimes, artists know.” Eight years on, that sentiment has started to override ARTPOP’s chequered history. The twisted exaggeration of pop’s most commercial motifs is now commonplace in the realms that once sniffed at that record. Unhindered visions are finally in.

What some said ARTPOP had failed to do — in trying to make commendable, interesting art from the most pedestrian pop sounds — is being manifested by those creating what we now know as hyperpop. It’s a subgenre reliant on abrasive, unpredictable synth work and the exaggeration of commercial, some say facile, elements of music. The Atlantic dubbed it “noisy, ugly, and addictive”. In retrospect, those words could apply to ARTPOP too.

With a roster of founding artists and associates, PC Music — the east London collective founded by A.G. Cook in 2013 — changed the way pop music was supposed to sound. The maligned tropes of the genre were reformed into strangely crystalline pop songs with simple melodies and clear-cut lyrics (see Hannah Diamond’s “Pink and Blue”). But that deconstructed, elemental way of producing also made way for something more obscure. SOPHIE soon bent pop sounds further on her debut project, including the single “BIPP” which dropped just weeks before “Applause” did. These artists were challenging the notion of what pop should sound like in tandem. They had the same objectives, only in vastly different realms.

Hyperpop’s early days were fundamental for what would come over half a decade later, as the genre expanded into music that arguably feels more in keeping with the thematic chaos of ARTPOP. 100 gecs, the producer duo formed of Dylan Brady and Laura Les, are now synonymous with the genre. The plasticky sound of what PC Music’s cohort makes prevails, but there’s a melting pot of more aggressive notes within it. Untameable dubstep, punk, trance, screamo and Europop overlap, each layer considered but, when listened to with a layman (or non fan’s) ear, sounds like mayhem.

As a group, they’ve criticised the idea that what they create is rooted in “irony”. It’s a common misconception that hyperpop exists in some sort of haughty, experimental realm which rips into pop music rather than creating something that makes full use of its most jubilant qualities. A 100 gecs song sounds like the feeling of sinking several cans of Monster and getting the shakes afterwards. It’s weirdly transportive.

It’s also hugely misunderstood by many. There was, at the time, a significant feeling that maybe Lady Gaga’s ideas for ARTPOP had gone over the heads of people she thought would understand her vision. What 100 gecs creates isn’t entirely present in ARTPOP — some may say Gaga’s project was less refined, the chaos representative of what existed around the record as well as within it.

But what ARTPOP and hyperpop share is an understanding that the binary definitions of genre are there to be played with, as if they didn’t even exist in the first place. ARTPOP’s crunching chaos — from balladry about “gypsy life” to saying “mount your goddess” completely deadpan over sexed up EDM — was a rebellion few major label artists at the top of their game were willing to make, fearing the consequences.

But hyperpop’s reputation relies on rebellion being the central focus of what is created. Still, PC Music’s stars and affiliates have crossed over into the mainstream. EasyFun, for example, writes and produces for Rita Ora; SOPHIE worked in the studio with Gaga for Chromatica. But their knowledge of the genre is so expansive that their presence is now welcomed rather than scoffed at. Fundamentally, a shift has occurred — 100 gecs now share a label with Ed Sheeran.

How funny to think that it would take over half a decade from ARTPOP’s release for chaos in pop music to go somewhat mainstream. In some ways, we can thank the pioneers of hyperpop — a genre that frames pop as an abrasive, challenging force — for helping a record by the world’s biggest artist experience its second moment in the spotlight.

There was once a time when Gaga told her fans that ARTPOP was made with “a tremendous lack of maturity or sense of responsibility”. On the contrary, eight years later that uninhibited, reinless approach feels emblematic of a wisdom beyond her years.