For centuries, London’s East End has occupied a mythic space symbolising the stark realities of class, racial, and ethnic divide in the UK. Tucked along the Thames, it became the centre for shipping and heavy industry, quickly creating a harsh landscape rife with poverty, pollution, overcrowding, disease, addiction, and crime ripped from the pages of a Charles Dickens novel.

Within the East End lies Whitechapel, an ancient parish that rose to global notoriety with the explosion of the halfpenny press in the late 19th Century. Sordid stories of “how the other half lives” whet the appetites of readers following the latest Jack the Ripper headlines. At the same time, the East End became enshrined in high culture as writers like Oscar Wilde, Jack London, and George Orwell drew upon the forbidden fantasies and harrowing truths nestled within its layered histories.

During the 20th Century, Whitechapel became a battleground with attacks coming from all sides. In 1936, radical right wing politician Oswald Mosley led the British Union of Fascists in a march on the East End, which had a large Jewish community at the time. Thousands of antifascists came out to block the march, only to have police turn on protesters in what became known as “The Battle of Cable Street.” The police withdrew in defeat and demanded Mosley send his band of Blackshirts away.

Although the people won, peace was short lived. Just give years later, Germany unleashed the Blitz, targeting the East End to destroy the city’s primary industrial, storage, and shipping facilities — decimating civilian life in the process. After the war, the East End was derelict, depopulated, and left to fend for itself. With the docks closed and railways cut back, industry spiralled into decline while “urban renewal” projects, which began in 1890s, had ground to a halt.

With the rise of Swinging London in the 1960s, the East End once again stood in the shadows of a brutal class divide. While the legendary Kray twins fed the public’s desire for stories of glamour, gangsters, and true crime, material conditions remained bleak for the community writ large.

In the summer of 1969, David Hoffman arrived in London after finishing his sociology studies at the University of York. As a teen, he did a wide array of odd jobs to make ends meet, including selling photos to the Yorkshire Evening Post and university newspaper — but quickly realised they wanted feel-good fare, not the deeper exposes into the human impact of structural inequality.

In 1971, David met up with some friends from York who were living in Whitechapel, and stayed with them for a spell before renting a room above Solly Granatt’s jewelry shop in Black Lion Yard, a narrow alley dating back to 1746 that became known as the ’Hatton Garden of the East End’. But David was living on borrowed time. In 1966, the city council designated the historic street for slum clearance. “Black Lion Yard was demolished and became a government banking hub for people in suits. It was a beautiful Georgian Street and now it’s just gone, like it never existed,” he says.

In September 1973, David moved to Fieldgate Mansions, a sizeable complex built in 1905-7 as part of an early commercial redevelopment strategy. It originally included 34 red brick buildings, each with eight 1-bedroom apartments with indoor plumbing at a time when it was rare. But in time, it fell into disrepair at the hands of slum landlords. By the time David arrived, many local properties in the area were left empty, drawing a broad swath of squatters from all walks of life, alongside the community increasingly comprised of Bengali immigrants.

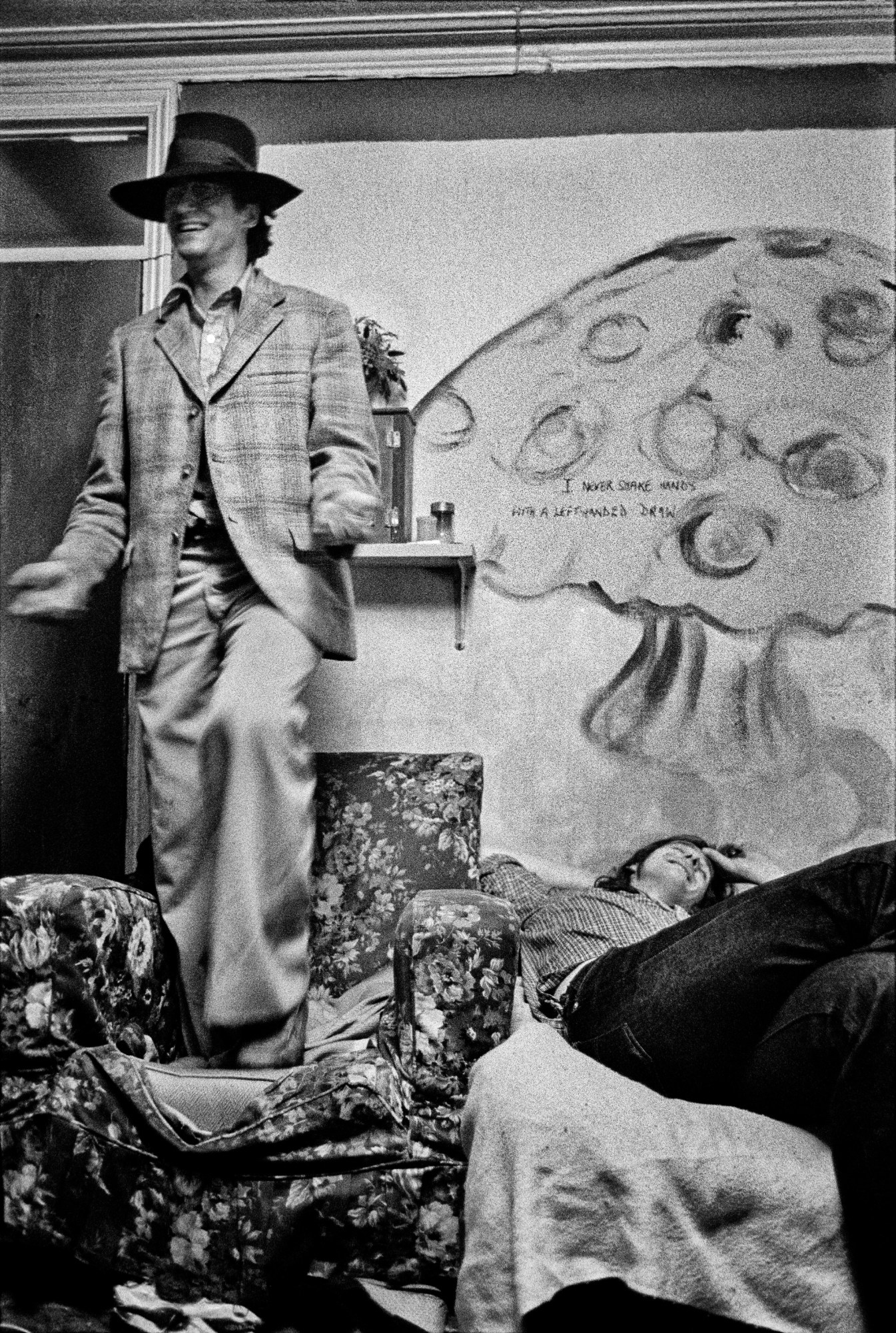

Fieldgate was home to an extraordinary mix of artists, bohemians, eccentrics, workers, pensioners, hustlers, and thieves who came together as a community to fight back against efforts of the state to push them out. With the publication of Fieldgate Mansions 1973–1985 and Around Whitechapel 1972-1992 (Cafe Royal Books), David looks back at this pivotal period of East End history — just as he was getting his start as a photojournalist.

“Whitechapel was a very derelict area; there were still lots of open ground where buildings been bombed in the war and most of the property was in very poor condition,” David says. “It was anarchic because it was all falling apart and it wasn’t very regulated. Many people were living rough, sleeping and dying on the streets. Homeless alcoholics and heavy drug users tended to gravitate towards Whitechapel, partly because there was a safety in numbers. That also meant services for them the area, and I think that helped.”

As the state ramped up evictions, the community was split between long time residents shattered by the relentless grind of poverty and a new generation of residents committed to collective resistance. “Many people were old, living on a pension or benefits, and didn’t have any power so when the council said, ‘We’re going to move you to a place with a separate bathroom, no leaks, warmer in the winter, cooler in the summer,’ most people swallowed this,” says David.

But squatters rallied as a force, joining together to fight against eviction from nearby private properties, which David chronicled in Parfett St Evictions 1973. Published in 1976 during his final year at college, David later learned this work comprised the very first British protest photography book.

“Whenever there was a sign of an eviction, lots of people would turn up and stand in front of the doors,” says David. “They built barricades and had guard dogs. The bailiffs left in defeat but would come back at four in the morning and knock in the door with a hammer. The houses would be put up for auction and one of the squatters, Doris Lerner, would go along in posh clothes, looking very suave. Houses were sold to squatters so this delayed things for a couple of months.”

Looking back at this era, David sees how much has changed within his lifetime. It’s no longer possible for a rag tag band of squatters to band together, occupy an abandoned property, and refashion it to their needs. “The world has become so regulated and people are much more tied down than we were,” he says. “We were able to wander around markets in the evening when it was quiet, pick up bruised apples and overripe avocados, and live of that. I was very young and all my friends were anarchists. There was that feeling that the establishment was working to keep us down. Housing was very hard to come by and was shitty. Jobs, when you could find them, were crappy and underpaid. We had to look out for ourselves.”

‘Fieldgate Mansions 1973–1985’ and ‘Around Whitechapel 1972-1992’ are published by Cafe Royal Books

Credits

All images courtesy David Hoffman