Oliver Frank Chanarin is on a journey, driving north from Barcelona up into the Spanish mountains where he and his partner recently purchased a plot of land. With the help of a local excavator, Oliver has spent the past few weeks digging “a very large hole” to be used as a water reserve for the home that will eventually stand beside it. “It’s getting pretty big now — the hole,” he tells me excitedly. “I’ll send you a picture.”

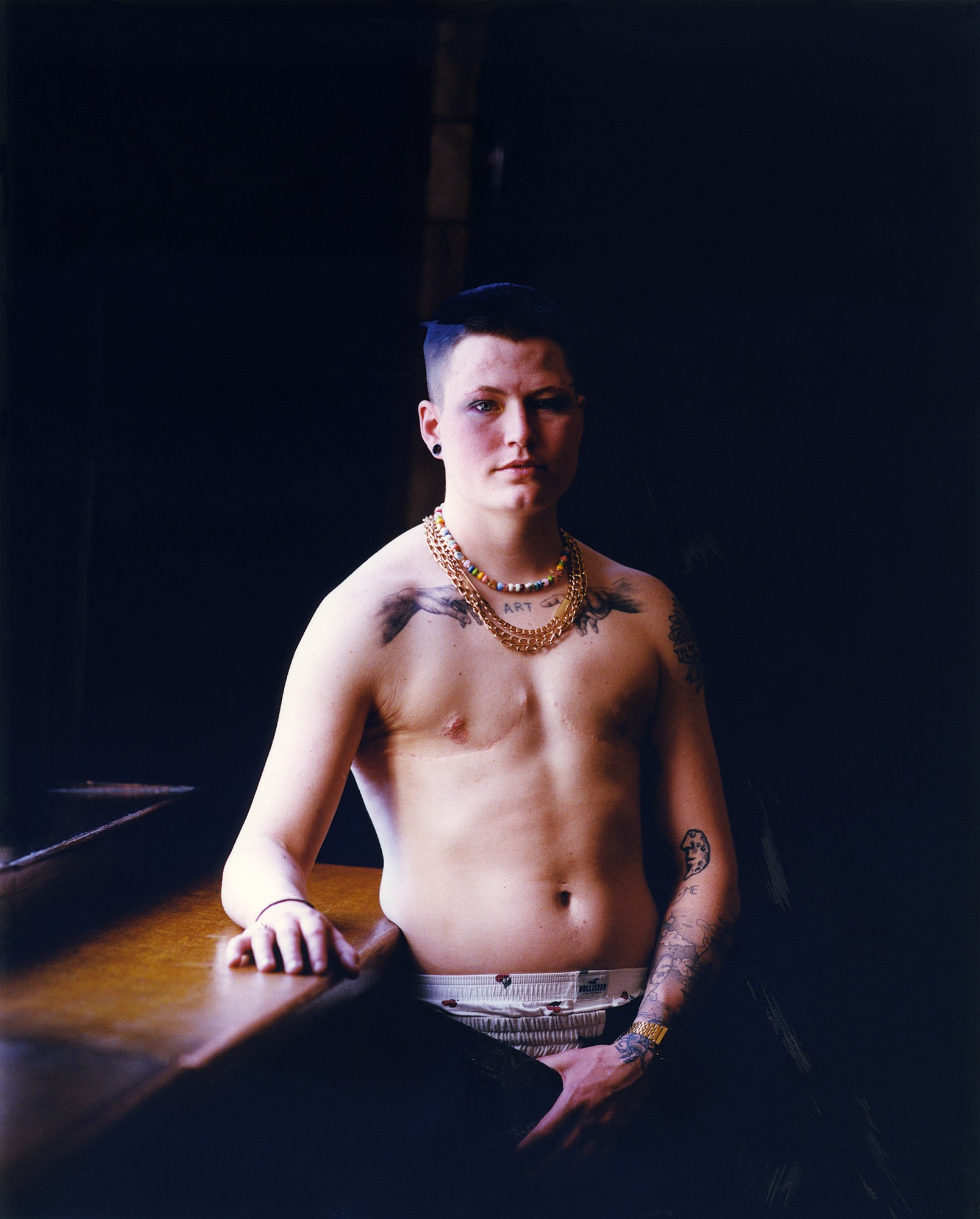

A couple of years ago, Oliver set out on a very different journey. Or, a number of journeys across Britain, investigating “the shifting terrain of documentary photography: our drive for attention, the complexity of being seen and our anxiety of being overlooked.” The result was A Perfect Sentence, an ironically, or as Oliver puts it “aspirationally”, titled photo book chronicling his journey.

The text Oliver wrote to accompany the images is a lyrical meditation on the complex ethics of documentary photography and the role of the photographer within that. “I’m not a writer, but I was kind of channelling W. G. Sebald,” Oliver says, somewhat shyly. “The act of journeying and recollection. I wasn’t able to take notes while I was taking the pictures because it was too much to focus on. Then, later, I sat down with all the images and tried to write from memory.”

In Austerlitz, one of W.G. Sebald’s most famous novels, the titular character observes: “I feel more and more as if time did not exist at all, only various spaces interlocking according to the rules of a higher form of stereometry, between which the living and the dead can move back and forth as they like, and the longer I think about it, the more it seems to me that we who are still alive are unreal in the eyes of the dead.”

I am reminded of Oliver’s opening passage: “I focused my attention, finger tips pressing on my temples, the sound of sand sifting across the sea bed effacing everything. Decades of sand deposits from further up this eastern coastal boundary had accumulated by stealth, gradually robbing beaches elsewhere and building underwater dunes, now separating the sea from the road.”

“I’ve been taking photographs for the past 20 years,” Oliver tells me. “And for most of that time, I thought I could walk into a room with a camera and be perceived as neutral. I wasn’t aware of the impact I was having. So making this work has been really confronting for me because, from the beginning, it was evident there was nothing neutral about me.”

Oliver’s initial plan was to travel across the UK, conducting an ethnographic study of post-Brexit Britain, inspired by photographer August Sander’s long-running research project, People of the 20th Century, which documented the lives of ordinary Germans over one of the most seismic periods in the nation’s history (1910 to 1954). August invites us to witness a pastry chef working over a copper pot, a farm labourer heaving a scythe along a dirt road, a circus performer standing in front of a painted caravan. Some sport naughty, even conspiratorial smiles. Others stare defiantly down August’s lens. The project was, in his own words, an attempt to distil “the complexity and universality of the human condition”.

There is an implied intimacy to all portrait photography that is often accompanied by a guilty thrill at gaining unearned access to a stranger’s life. Viewing August’s photographs through a modern lens, the feeling of trust between photographer and subject feels almost anachronistic, in contrast to the formality we tend to associate with early 20th century portraiture. August’s compositions are often subtly witty and, as Oliver puts it, humane.

However, Oliver increasingly felt that August’s 20th century approach did not lend itself well to a document of 21st century Britain. “It just didn’t relate to how people define themselves now, when a man can be a father, a son, a bricklayer and a fetish enthusiast all at once.”

Moving away from August meant deviating from the plan Oliver had originally pitched to the project’s backer, Forma. And without the reassuring structure of August’s work, Oliver found himself questioning his instincts. “I’m not very good at inventing something out of nothing,” he writes in the accompanying text. “Brexit had revealed how disconnected my political and social views were from the rest of the country. I knew the answer was to go back to the impulse that drew me to photography in the first place. Encounters with strangers; the beautiful accidental moments that come with getting lost in the world with a camera.”

The conditions were strange in a number of ways. The world had constricted unexpectedly due to the Coronavirus pandemic, and Oliver’s long-running and hugely successful collaboration with artist Adam Broomberg had recently come to an end. “I’d never done anything on my own, so it felt like starting again. I felt unmoored, like a planet that had lost its moon.”

This sense of loss echoes through the book in waves. When Oliver goes to visit a group of volunteer wound specialists, he recalls reaching out to them with Adam years before. “This was 15 years ago, when Adam and I were an inseparable artist duo, propelled through life on undiluted chutzpah and a shared fascination with photography and each other. It was a beautiful collaboration that lasted over twenty years until, like two small brain cells starved of oxygen, it eventually withered.”

On the first journey Oliver undertook, he was invited to teach a workshop to a group of teenagers in a community art centre. He taught them to take portraits using a large-format camera, processing the images in a lightproof tent. A photography assistant, Lucy, assisted throughout the workshop.

Afterwards, the group ate pizza together and took phone pictures of the “blurry, otherworldly, inverted” portraits they had made of each other. That night, before going to sleep, Oliver posted one of the pictures on his Instagram — a black-and-white portrait of Lucy. He wrote, “Thank you everyone for a great evening. Thank you Lucy for helping make this picture. See you soon.”

The next morning, Oliver woke to see a message from Lucy asking him to delete the picture. He had not had permission, she said. Oliver deleted the post and apologised. Later that day, the gallery Oliver had been working with on that leg of the project called him in for an urgent meeting. A lawyer had been consulted, and Oliver was informed that he had breached their safeguarding policy.

“In what felt like a ferocious act of erasure,” Oliver writes, the photographs made by the participants in the workshop were confiscated and destroyed. “Then, bewilderingly, all other plans for my visit to the city as well as the exhibition itself, were cancelled. Any images I had already made were embargoed… Afterwards I looked more closely at the safeguarding documents… Yes, I had transgressed, it was all there in the small print. We experienced what happened in that city by the river, where the boats churn slowly in the water, as a trauma.”

After that, the production process around Oliver changed radically. Getting lost and encountering strangers was now deemed too high-risk. Each stage of the journey now required meticulous forward planning. Where he had dreamed of travelling alone, he was now accompanied by a team of people tasked with gathering release forms, doing risk assessments and safeguarding anyone he interacted with. A team of one had turned into a team of four, which quickly became expensive.

“It was just a very different thing,” Oliver says. “Moving through the world as a group made spontaneity impossible. Everything had to be discussed and agreed in advance. I’m not saying this was entirely a bad thing. Historically, the power dynamic has always skewed in favour of the photographer. There’s been a shift, and now the person in front of the camera has more awareness of their power. That’s a good thing. It just means that a certain kind of, let’s call it, ‘street photography’, may no longer be ethically possible.”

It occurs to me that Oliver could have abandoned the project at this point. The pain of what he describes as his “misstep” with Lucy reverberates through the whole book, taking on a life of its own, as trauma does in the body. The book opens with a list of the boundaries, including ones Oliver transgressed by posting the picture of Lucy. They are presented almost as commandments, a manifesto for more equal power dynamics between photographer and subject.

“Don’t reduce me to tears as a form of control.

Don’t allow my allegations to go unrecorded.

Don’t assert your authority through sarcasm.

Don’t take me in a car on a journey alone.

Don’t capture my image without consent.

Don’t do things for me that I can do for myself.

Don’t walk with your hands in your pocket.

Don’t contact me.”

Opening the book in this way feels almost like an act of repentance, even self-flagellation. One can imagine a list of contrite commitments scrawled on a chalkboard: I will not capture your image without consent. I will not contact you.

The book’s accompanying text begins in a similar vein, with a melancholy recollection of standing on a beach, Oliver pressing his fingertips into his temples, contemplating the decades of sand that must have migrated from someplace further up the coast, “gradually robbing beaches elsewhere”, in order to end up before him at that precise moment:

“I pushed harder with my fingertips until the edge of my nails started to make it hurt: the sound of the turbulent, pounding sand incrementing with the pain. Other images flashed across my mind: the greyhound dogs parading ahead of a race; empty food shelves in the mini supermarkets that had mushroomed along the main street suspiciously offering nothing much – cigarettes, vapes, Doritos; crowds of West African workers, via Portugal, assembled at the city centre at three a.m. waiting for the free transfer by coach to the Bernard Matthews turkey factory; a coffin-laden hearse, always the same but always different, parked outside St. George’s Church for afternoon funerals.”

Later in the book, when visiting a military barracks in a coastal town, Oliver notices a screen displaying security status updates: “threat of attack medium; threat of attack high; threat of attack low”. In other words, the threat of attack is constant. I am reminded of this moment when, during our conversation, Oliver references a line from Wim Wenders’ memoir, that “the most political decision you make is where you direct people’s eyes”.

In A Perfect Sentence, Oliver consistently directs our eyes towards elements of perceived threat but finds relief and much hoped-for and planned-for joy on the fringes. We experience a shibari session, visit an ailing zoo, a Rolls-Royce factory, a homeless shelter, experiencing glimmers of the community and Britishness and chaos that Oliver had been questing for inextricably interwoven with the requisite awkward encounters, miscommunications, and missteps.

An integral part of the project was the community workshops that Oliver had proposed to facilitate along the way. But when spending time with men at a homeless shelter in the South-West of England, Oliver found himself asking what he had to offer them of tangible use. “As it often seemed,” he writes, “my role here was tentative and ambiguous: a witness; an interlocutor; a teacher, a friend. Taking photographs of these men wasn’t going to help them.”

Coming from the cloistered world of conceptual art photography, this kind of confrontation was new for Oliver. “I realised I had moved through the world in this kind of frictionless way. Gathering images of people and places and bringing them home, like a squirrel collecting nuts. So that, in a way, they became my property.”

Spending extended amounts of time in unfamiliar social dynamics without the protective shield of concepts or theories forced Oliver to contemplate the undeniable weight of his identity within those spaces. It isn’t possible to move frictionlessly through the world; he had just never been around to feel the burn. Now he was feeling it: all of the exquisite humiliation and discomfort and release that comes with making oneself truly vulnerable.

But in A Perfect Sentence, Oliver is far from the main character. Amidst the humour, humiliation, tenderness and joy, there are people from all walks of life and all over Britain living wildly divergent lives. The only connection between them, beyond shared citizenship, is that Oliver has chosen to direct our eyes towards them, no matter the friction this causes. And as we perceive his subjects, they stare back at us, too.

‘A Perfect Sentence’ by Oliver Frank Chanarin is published by Loose Joints.

Credits

All photography copyright Oliver Frank Chanarin (2023)

Courtesy Loose Joints