Rene Matić has been thinking a lot about endings. They separated from their wife of seven years recently, and have since been reflecting on ideas relating to death, transition and the perishable. Moments of joy can be particularly fleeting for the queer community, where there’s a reliance on spaces like gay clubs and underground music venues that are all too often temporary, says the artist, “almost as if they have to be because when things linger on too long, they get infiltrated and stopped.”

Worried that the intimacy and truthfulness of their own work might be changing as they become more well known, Rene has decided that their solo show at Chapter NY will also put an end to an ongoing photography series, flags for countries that don’t exist but bodies that do, which documents these safe spaces, the people closest to them and the persistence of love in hostile places. It’s intimate work, shot on a 35mm camera in living rooms and kitchens, backstage and in queues: a chronicle of queer life in Britain.

Rene thought the project would go on forever, “in the same way that I naively thought that a lot of things would last forever”, they say, but things don’t happen by accident as much anymore, there’s more awareness and the images have taken on a life of their own. “I’m questioning what it means to have a camera and to survey those spaces if I’m bringing a whole other audience into the space by having that image in a gallery,” Rene says.

Named after a text message they would send their friends whenever they’d see Rene’s wife, Maggie, kiss them from me alludes to an absence: “I’m not really there, but I’m still passing something on.” The photographs are taken from a body of work that has been several years in the making, and looking back — watching friends grow up and transition, physically and mentally, and shifting class as their careers take off — has been emotional for the artist. “I think there’s quite a big sadness for me about this show, it feels like a grieving of the series and also of other things — it’s like growing up.” Or, they say, “like admitting defeat.”

Rene met Maggie on Instagram in 2016, and was married soon after in Liverpool at the age of 19. “It’s crazy and it’s wonderful, and has definitely been the thing that has shaped me the most: the love that I’ve learned about and the care.” Initially, the artist wanted to create a show about how cross they were feeling about how hard it is to keep the world out as an interracial queer couple, and wanted to name it: “I stay alive for you.” But Rene didn’t have the strength to do that show, as the separation was too fresh and painful.

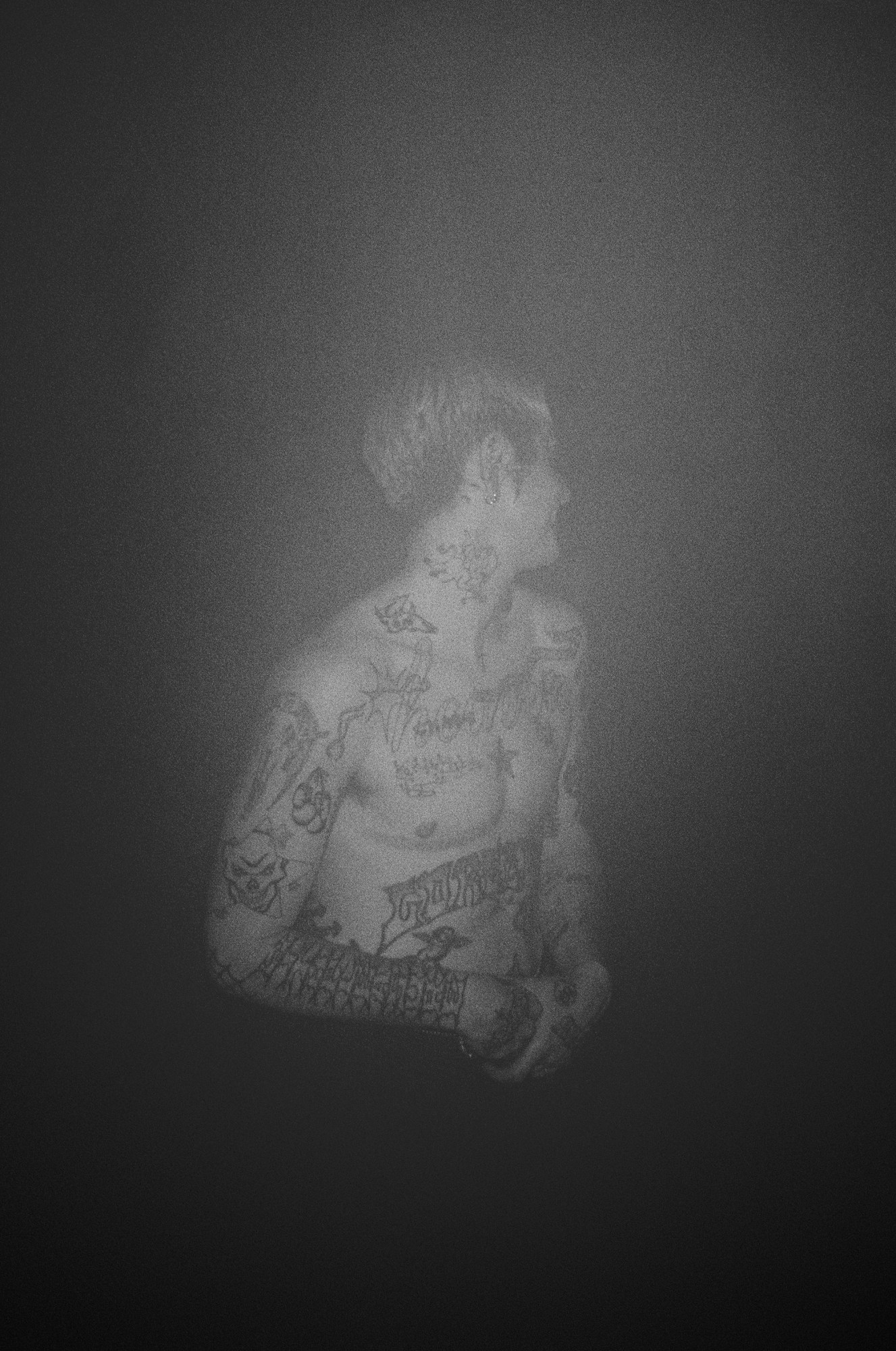

Instead, Rene has selected portraits of trans bodies in protest and celebration: a couple in red mesh at Glastonbury with a union jack hand-painted on one of the revellers’ skirts; the performer Travis backstage at the Hammersmith Apollo; a person holding a sign that says, “I am thriving in spite of this country.” “I want to show an othering of the other. Like to continue, the othering. I think it’s kind of powerful,” they say. “To not have to have these identities that people think they have a pretty clear view of. To skew that is important.”

Two poignant photos sit beside each other in the show: an image of the flowers to mark the Queen’s death, and candles at the vigil for Brianna Ghey — the 16-year-old transgender girl that was murdered in Cheshire — that encircle the word ‘human’. Both show death and grieving, on very different scales, and, like much of Rene’s work, draw attention to power structures at play. Importance is placed on one life rather than the other, which feels wrong — one life and person, surely, does not mean more than the other.

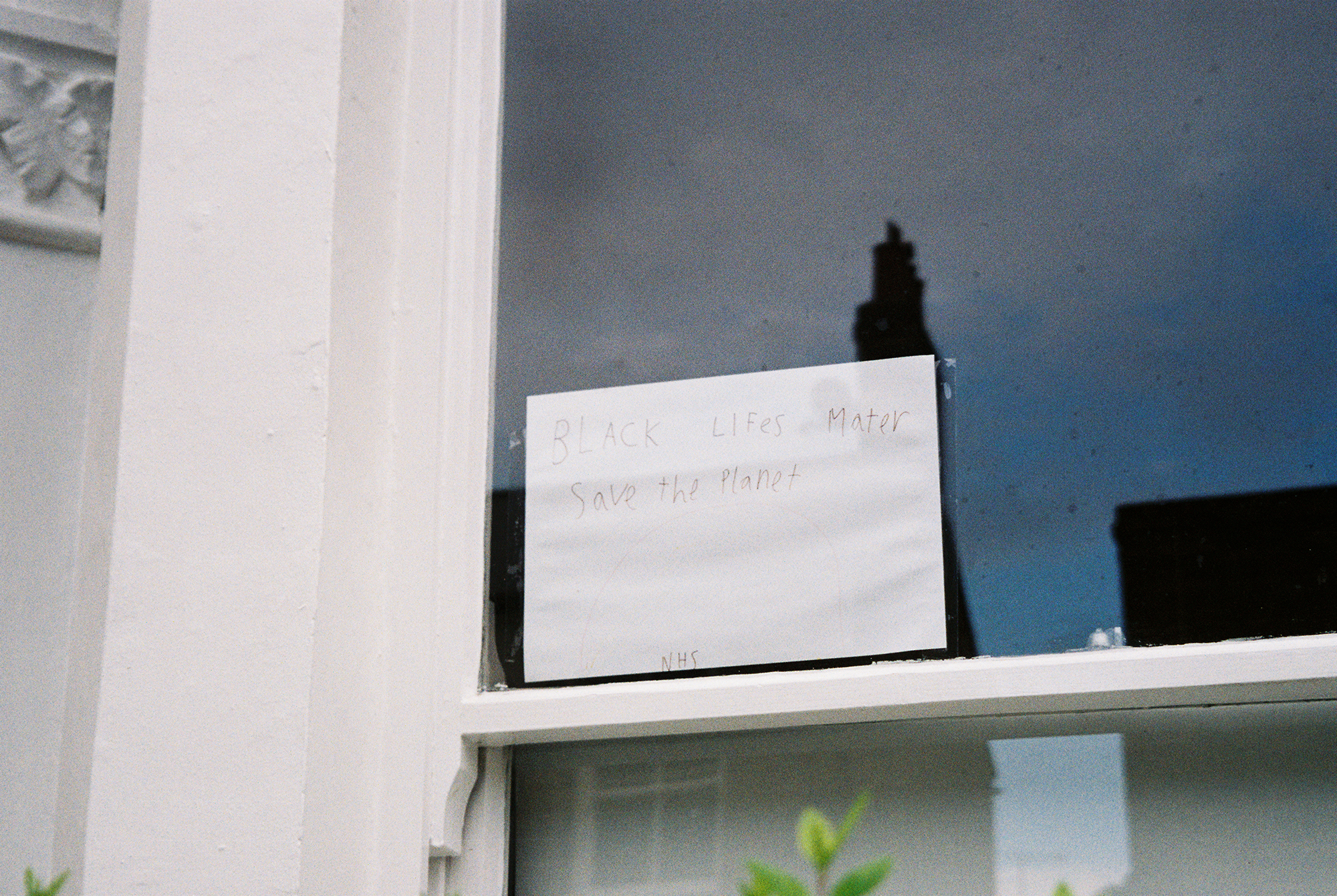

Throughout the images, text plays a key role: graffiti, notes, fleeting feelings and subliminal messages. A hand-written note on white A4 is found in a window in Peckham reads ‘Black Lifes Mater, Save the Planet, NHS.’ “It’s almost like a desperation,” they say. “Like desperation on desperation on desperation — me taking a photo of someone else’s desperation is me being desperate and like, this kind of call to action.”

Symbols of nationhood and religion are also speckled throughout the exhibit, loaded with a passive aggressiveness towards a Britain that has so much wrong with it and a government that seems unlikely to change. “Marriage to a person of the same gender was never meant for me. In the same way that the tattoo on my back, ‘Born British Die British’ was never meant for me,” says the artist, who reclaims the far-right slogan. Hanging in their show, the emblems are subverted from their original meaning.

Rene grew up in the Brexit town of Peterborough in the East Midlands, which they describe as “beautiful and inspiring” but at the same time “deeply problematic and awful.” In a place where everything goes, they say, often it does for better or worse. Last year, the artist explored their mixed-race heritage in a show at the South London Gallery called Upon This Rock, which included a video about their father’s experience as a British Jamaican skinhead. Back then, working-class kids would unite to dance to ska and reggae before the group took a turn to the far right.

References to dance are woven throughout Rene’s work: photographs taken in nightclubs and festivals, where bodies gather without needing to understand each other. It’s an out-of-language moment, they say, “it’s not Westernised, it’s not colonised. It’s a kind of utopia that can spring up anywhere.” But at the same time, there’s the knowledge that the dance floor won’t last forever, that it’s fleeting. For the queer community these spaces can be a relief and a way of survival, much like the fantasy of kink and dressing up, says Rene, who also captures Maggie in black latex, looking, Rene says, “fucking incredible.”

The whole show is defiant and full of love: a reaction to an environment that’s getting steadily more bleak in Britain. “The worse it gets the more numb you become, which is really sad,” they say. “But at the same time, the tighter my friendship group gets, that chosen family and the love, and the ways of survival get stronger, and we get better at doing that, which is not a good thing. Obviously, we have to protect ourselves.”

“I do look at love so much in my work, as a way of surviving and trying to find a way out of this kind of chaos,” Rene says. “The reason why I find [the show] quite sad is because it lets go of that a little bit. It’s tired. I think that really that’s what I’m feeling is tiredness: looking after myself and my family and my people. I’m tired of having to care and I’m tired of having to do this much labour for us to feel at least a tiny bit comfortable.”

kiss them from me is on show at Chapter NY from October 27 to December 9, 2023.

Credits

Courtesy of the artist, Arcadia Missa, London and Chapter NY, New York.