The Los Angeles neighbourhood of Altadena at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains, where Stephen Ross Goldstein moved last year, is a wildly different landscape from the vast red desert of his native Phoenix, Arizona — but it suits the 26-year-old photographer much better. “I think it’s hard to put physical or mental emotions into photographs, but using the foggy coast of the mountains to weave in and out of that narrative, and the portraits of friends and the people that I’ve met… It’s a metaphor for how I feel,” he says.

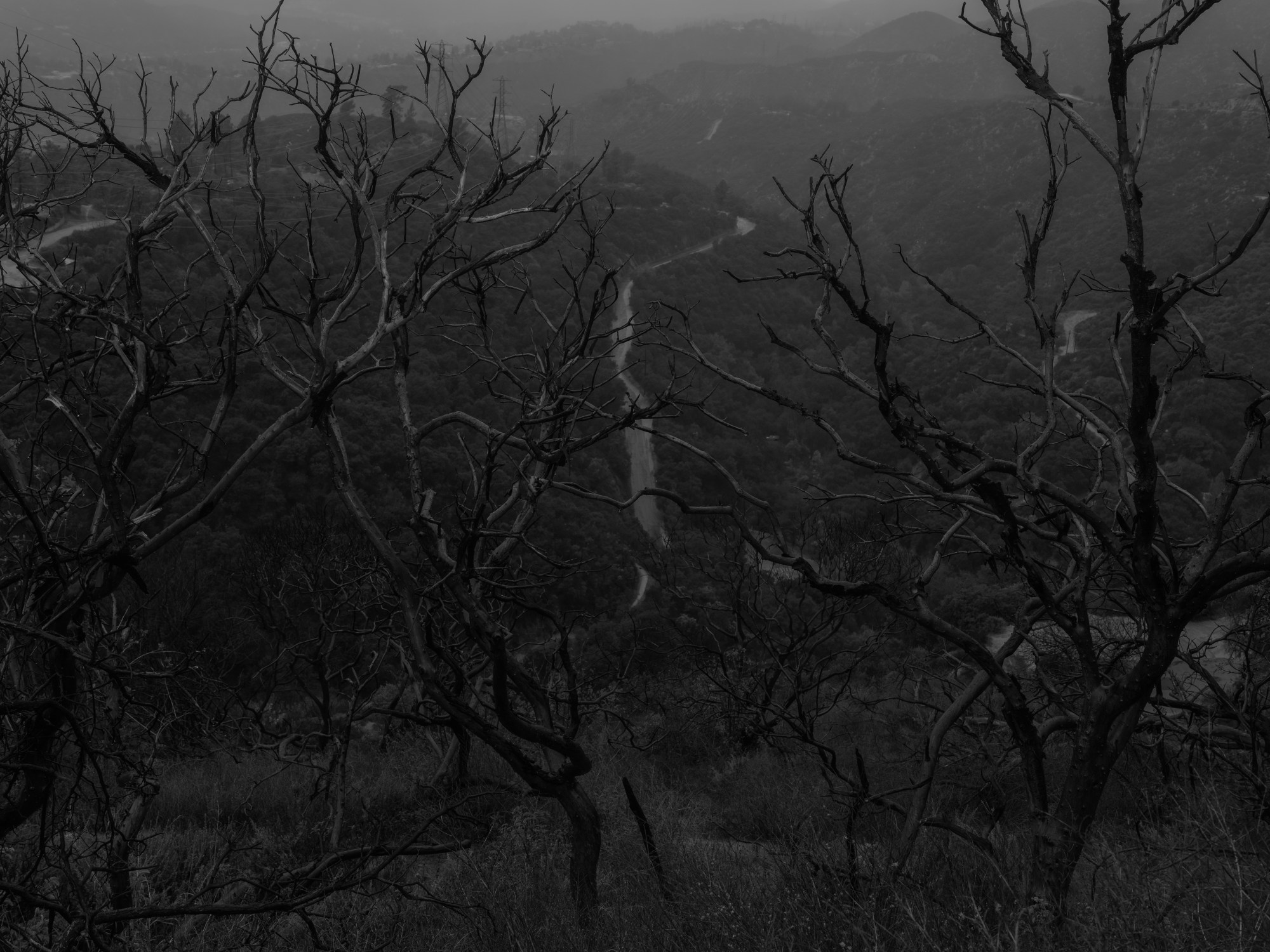

Photographing the inclement weather and complex landscapes has helped him put into pictures the anxiety he has felt about moving to a new place: the black and white images of fallen trees, rocky waters and tumbling waterfalls are full of melancholy and a sense of unease. “My work is a little bit dark,” he says. “I don’t shy away from the truth. I want to photograph people how they really are or places that are not so far out of reality.”

His ongoing project The Oak Echoes is a delayed coming of age story, he says, that’s “partially me emotionally and physically coming to terms with the diagnosis of an autoimmune disease that I had a few years ago, and finding community after moving to this new city to start over.” As much an exploration of his new hometown and a journey of self-discovery, as it is a celebration of his new friends and neighbours.

Stephen photographs his friend Brynne, running away from a waterfall during a hike in the mountains in January, on a treacherous day after heavy rain had raised the water to waist level. In another image, they lean against a tree: pensive, their eyes closed in thought. The moment is intimate and was unexpected, Stephen says, the light was suddenly turned perfect as they were looking at ants: “It opened up a sensitivity in my work that I think at that time last year that I’ve been playing off of.”

“In the past when I’ve photographed friends, I’ve been using a disposable camera at a party or a bar and I think it was a bit more spontaneous,” he adds. “Now I think it’s a more intimate thing to photograph friends. There’s a deeper connection as I’ve matured. I didn’t have that when I was younger.” Some of that comes from the time he spends with his subjects and his methodical approach. “A compliment I’ve gotten about my portraits is that it seems like I can photograph anyone who they really are, I’m not making them look extra good or worse or anything.”

Apart from a few candid group portraits of his friends playing chess on the side of a rocky path, most of the photos in the series are staged: “I like to see a moment and then will recreate it.” As a result, his work is full of love and tenderness: friends leaning on each other for emotional support or lying in the grass looking up at the sun in a way that is both cinematic and deeply personal.

Stephen is fascinated by photographers that came before him: the American greats like Mark Steinmetz, Robert Adams, his favourite Judith Joy Ross and the British photographer Chris Killip, who chronicled the deindustrialisation of the north of England. They all turned their lens on ordinary people in the places they lived. In particular, he references the Depression-era Farm Security Administration photographers commissioned to record American life between 1935 and 1944. Among them were Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, Arthur Rothstein and Gordon Parks, who focused on the lives of sharecroppers in the South and migratory agricultural workers in the Midwestern and Western states, as well as mobilisation efforts for World War II.

They chronicled poverty, migration, abandoned industry and over-farmed fields — periods of transition. The most successful ones were able to give dignity to a group of workers often dehumanised in the media and politics. One of Stephen’s favourite images is Dorothea Lange’s photograph of a farmer, working on a cotton farm in Arizona, with the back side of his hand covering his mouth and his hand looking huge: ”I find that to be the definition of a photograph,” he says. “I think that’s why I’m so fascinated by that era of photography, it’s so pure, black and white too. It’s not just the absence of colour.”

Like them, Stephen is drawn to ordinary people, landscapes and spaces rendering them hauntingly beautiful. Earlier this year, he was invited to photograph the 1920s interiors of an elderly woman’s home in his neighbourhood. She showed him to the out building, where her friend David lives, and is often found watching black and white Western movies. Stephen captures the floral curtains blowing in the wind that came through the half open door, and snapped several frames of the film that he’d pause at specific moments.

As interested as he is in documenting the lives of his friends navigating their early and late twenties, he’s also fascinated by the elderly residents in his neighbourhood like one man gardening, who he returned to photograph several more times in the year. “I met him when I was walking around Altadena, and he was telling me the history of the city,” Stephen says.

“I sometimes almost feel like I’m older. I photograph older people because I’m an old soul. Having this autoimmune disease makes me feel not my age, but I’m supposed to feel my age.”

Credits

Photography Stephen Ross Goldstein