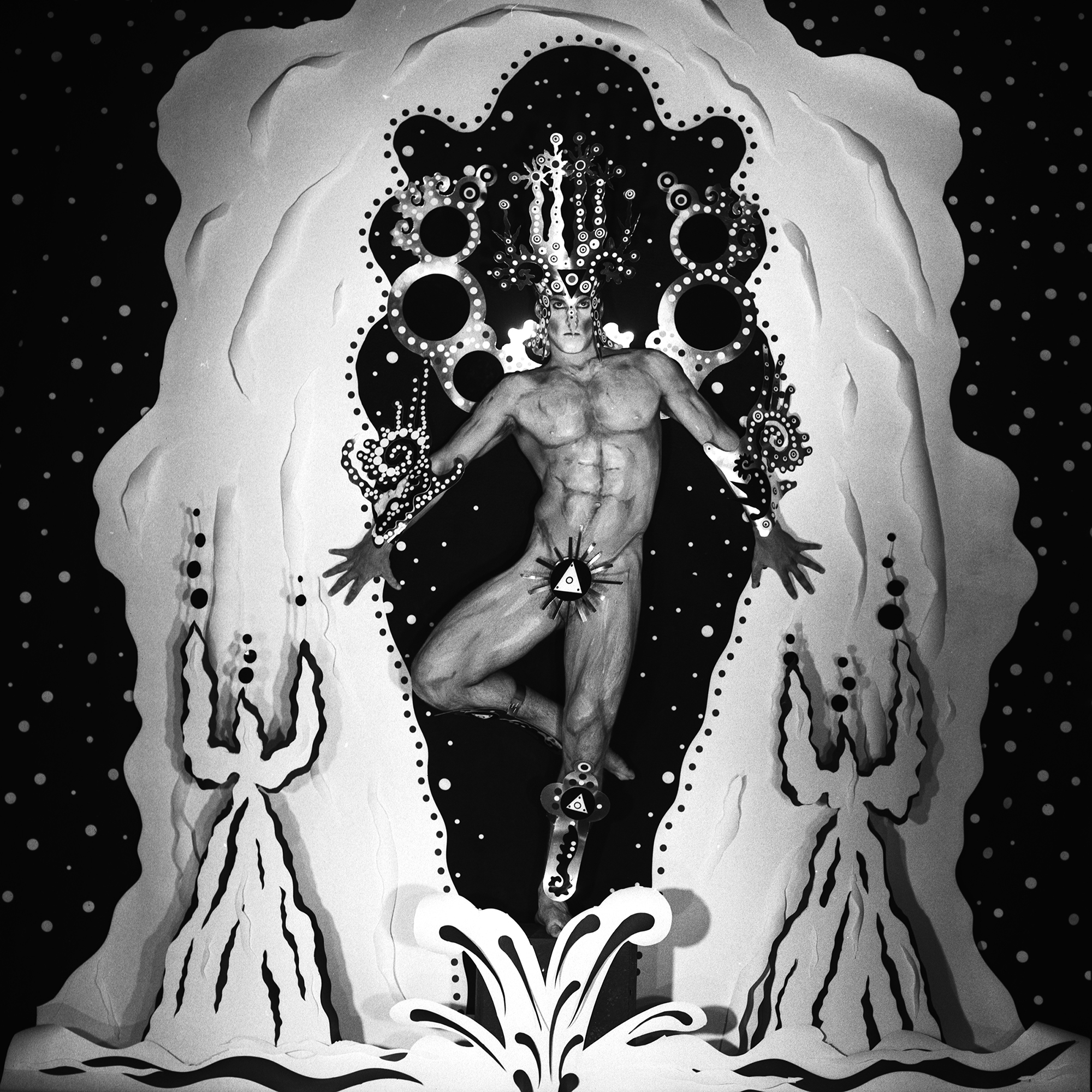

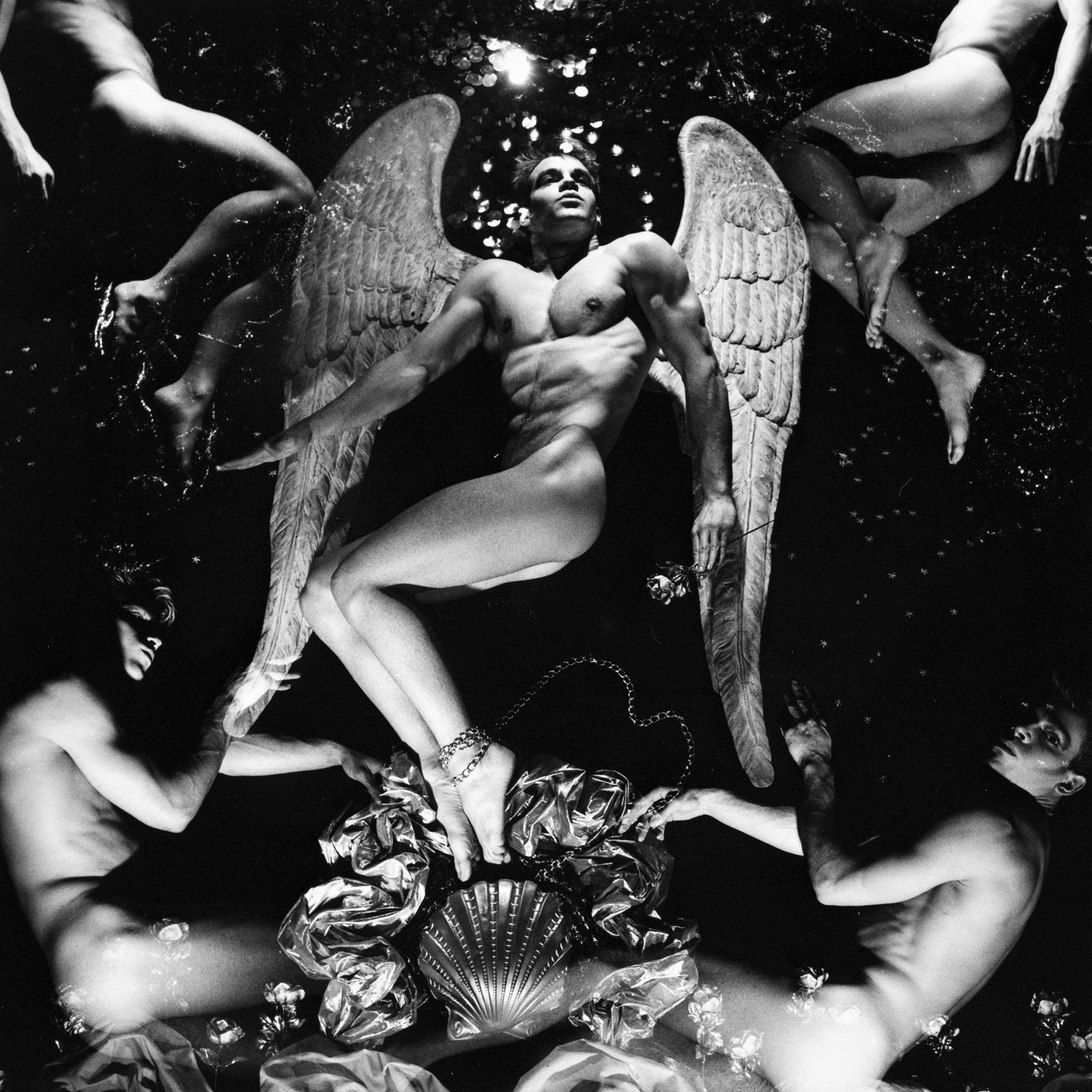

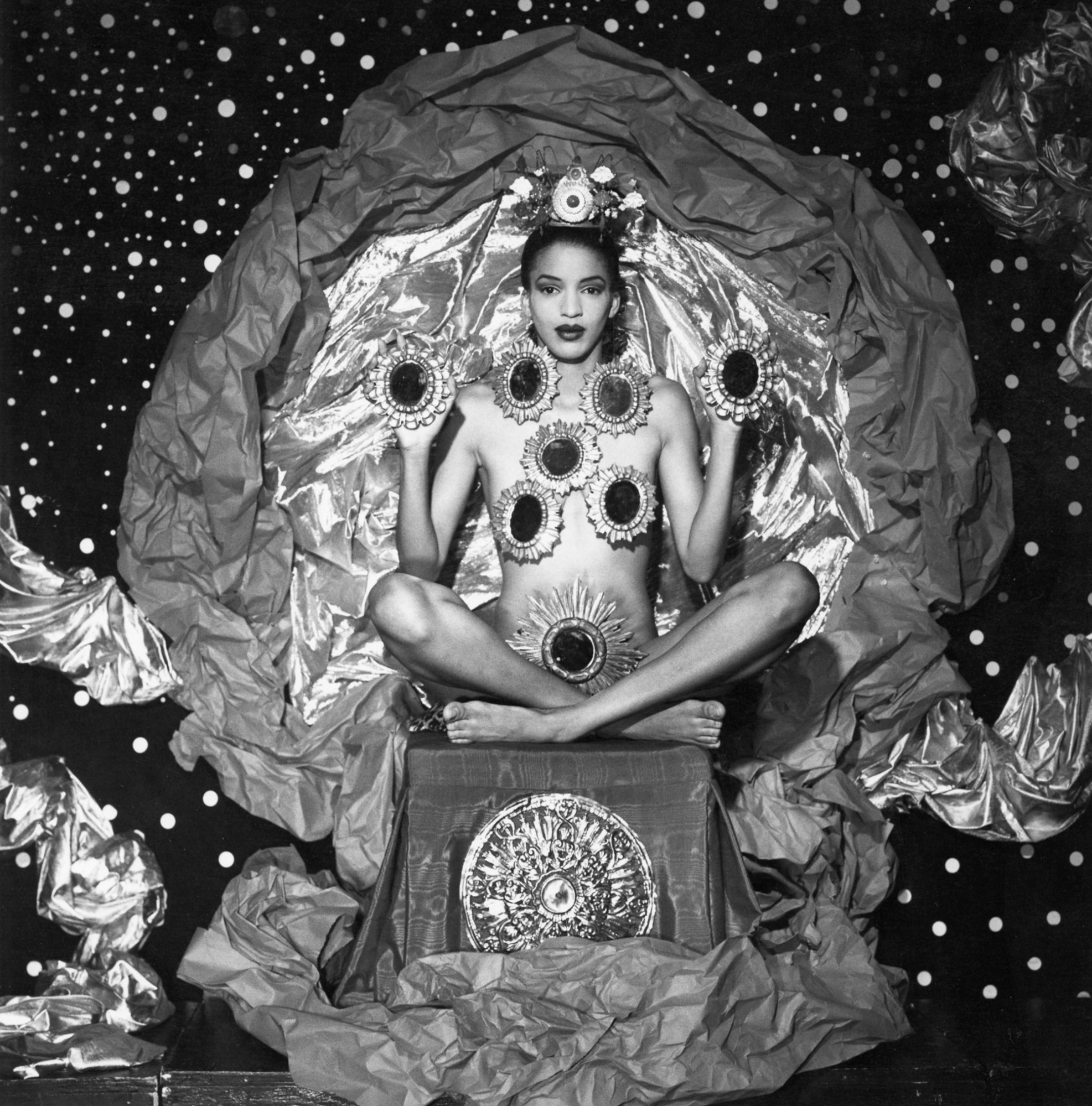

Standing at the forefront of the counterculture movement throughout his life, the artist and filmmaker Steven F. Arnold (1943-1994) planted the seeds of a revolution rooted in love. Embracing ancient archetypes that eschewed the false binaries of gender and sexuality, he developed a philosophy of queer mysticism that fused a wide array of religious, spiritual and cultural traditions. It was a magical celebration of both beauty and transcendence, embodied best by his tableau photographs of imagined queer gods and goddesses.

“Steven called it ‘androgyny of the soul’,’” Vishnu Dass, the director of the Steven Arnold Museum and Archive says. “From a young age, Steven was exploring gender fluidity and non-binary consciousness. That openness gave him a broad lens that broke down the walls of separation between himself and those around him. This translated into his work.”

Eccentric and theatrical, Steven recognised the hypnotic, bonding power of glamour, adornment and artifice. Steven intuitively understood that art could serve as a vessel for the divine energy that animated life — something which he would fully realise in his work in the years before his death from AIDS-related complications.

Steven’s sense of fun and play came during his childhood in Oakland, California. He spent countless hours in the attic of his family home creating sets, costumes and props for elaborate puppet shows. During high school, he met Pandora, who would become his lifelong muse and confidant. They would rendezvous in his bedroom for escapades of fantasy and bliss, playing dress up in bohemian clothes and studying mystic texts while sipping cocktails of champagne and cough syrup, and smoking joints laced with opium.

In 1961, Steven won a full scholarship to study painting at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). He then traveled to Paris to study at Ecole Des Beaux Arts but found he was not well suited for the narrow confines of academia. He hightailed it to a hippie commune on the Spanish island of Formentera instead. Three months and countless acid trips later, Steven returned to SFAI and and began making student films including his third, Messages, Messages, which synthesised his captivating vision of beauty, surrealism and esoteric mysticism. It was about, Vishnu recalls, “destroying who you think you are to find out what is at your core — that and openness and expansiveness.”

As San Francisco’s counterculture scene evolved from the beats to the hippies during the 1960s, Steven, then in his early 20s, was deep in the mix. “His very first job was lettering posters for Pauline Kael at the Cinema Guild in Berkeley, which is where he first found his love of film,” Vishnu says. Steven’s style and flair perfectly fit the style of the times. He designed psychedelic rock handbills for the Matrix nightclub, the Castro District’s Bead Shop, and Haight-Ashbury’s first vintage clothing boutique In Gear. While working at India Imports in the Haight, during the Summer of Love, Steven sold Jimi Hendrix his first sitar.

“Steven had several studios in San Francisco and everybody would gather around him because he was interested in design, fashion, architecture, and philosophy,” Vishnu says. “During the 1960s in San Francisco, there was a dissolution of the self that happened as a result of the psychedelic revolution and the Free Love movement, and people had been coming together in [what felt like] a new way.”

After releasing Messages, Messages in 1968, Steven, and his film collaborator Michael Wiese, decided to make the San Francisco premier a night to remember. In February 1969, they rented the Palace Theatre in North Beach and sold out all 2,000 seats on opening night. Impressed with their savvy, the theatre owners invited them back — and one month later they launched the Nocturnal Dream Shows, the nation’s first midnight movies showcase.

Each week, Steven and Michael curated a hypnotic collection of film fantasia that included vintage pornography, Betty Boop cartoons, and sci-fi and surrealist films from the 1920s for audiences that often included Janis Joplin, Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams. He also gave legendary avant-garde theatre group The Cockettes their start on Halloween 1969, which would eventually introducing the world to soon-to-be luminaries like Divine and Sylvester. As impresario, Steven sometimes dressed in drag, famously wearing one ensemble that made the rounds in underground magazines of the time, remarkably prefiguring the sensational dominatrix style of Tim Curry’s Frankenfurter in the 1975 cult classic The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

By the time Rocky Horror took midnight movies mainstream, Steven was cavorting with Salvador Dalí. Steven hit the global stage in 1970 when Cannes’ Directors Fortnight presented Messages, Messages, and then again in 1972, when they showed his first full-length feature film, Luminous Procuress, featuring Pandora in the starring role. That same year, Steven met Dalí at the St. Regis Hotel where the maestro arranged a banquet screening attended by the crème de la crème of New York artistic society. This led to the film being included in the Whitney Museum’s New Filmmakers Series. Soon thereafter he was brought into the Court of Miracles, a madcap private circle that included Donyale Luna, Amanda Lear, Mick Jagger, Ultra Violet and Marianne Faithfull.

Dalí embraced Steven as his protégé, dubbed him the “little prince”, and brought him to Spain so they could collaborate on the inauguration of the Teatro Museo Dalí. “Dalí inspired Steven to make his interior world external, which is something he had been doing for a long time, but I think his time with Dalí really catalysed the idea of translating one’s dreams, visions and fantasies into art,” Vishnu says. “The biggest thing Steven got from Dalí was showmanship. When Dalí was at home in Spain painting, he would wear pyjamas and his moustache would be floppy, but when he was in New York or Paris, he would be screaming, beating his cane, walking around with anteaters on leashes, and throwing ocelots at people. Thank goodness Steven was never as maniacal as Dalí. It comes from that 60s ethos of love and connectedness.”

After leaving the Court of Miracles, Steven made his way to Los Angeles during the late 1970s, establishing the Zanzabar Studio which would soon become a magnet for artists, musicians, designers, poets, misfits, drag queens, and hustlers. “Steven wanted to be free from the polarised politics of the world, so he created his own universe that people could enter,” Vishnu says. “He had several different waves of people over the years. If someone came in and showed creativity in the way they were presenting themselves he would adore it, even if it wasn’t great, because he wanted to encourage people to keep going and to find their voice. He felt that making honest art was a way to heal, and he encouraged that.”

Between 1981 and 1993, Steve created his final series in the Zanzabar Studio: a pantheon of queer gods and goddesses set amid surrealist tableau photographs that are the apotheosis of his life in art. Collected in the new exhibition, Theophanies, opening 11 August at LA’s Fahey/Klein Gallery, the works engage myth, mystery, sexuality, spirituality, life, and death with Steven’s signature blend of splendour, spectacle, wit, and wisdom.

To create these hypnotic images of heaven on earth, Steven would wake up and head straight to work, storyboarding his dreamscapes — a practise he mastered during his filmmaking days in the early 1960s. Once the vision was clear, he would begin building the tableau using whatever materials he had. With little money at his disposal, Steven repurposed supplies like cardboard, metallic and patterned fabrics, buttons, cut paper, and paint. He then paired it with his extraordinary collection of antiques, vintage costumes and bric-a-brac.

“Steven would mark out a square on the floor, lay down matte back velvet, arrange all of these pieces, and then climb a ladder, look down, and let his vision expand,” Vishnu says. “If he was working upright, he would often have cushions, a candle and a Tibetan singing bowl. He would sit in front of the installation, open his consciousness, and go into a meditative state, [arranging] things until he got it right.”

Once the tableau was complete, Steven would style and paint his models, then instruct them in poses drawn from artists such as Michelangelo, Bernini and Camille Clovis Trouille. “Steven recognised the power of the image and understood the glamour he was creating was an illusion and a mirage,” Vishnu says. “He knew a good picture can cause a change of consciousness or a questioning of certain rigid values, but he was also exceptionally playful and never took anything too seriously. For example, the photograph ‘Inseminating the Marvelous’ features Steven’s favourite antique mannequin dressed to the nines and model Tony Ward, nude, with a comet issuing from his groin into the cosmos. The effect is simultaneously cheeky, sensual, sexy, reverent, and quite profound — with a humorous nod to the orgasmic, interconnected web of all matter.”

Although Steven died nearly two decades ago, his legacy lives on in the joyful embrace of gender fluidity and LGBTQ pride that he uplifted throughout his life. “I’m sure he came up against difficult judgments, but he was never in the closet,” Vishnu says. “Steven embodied and celebrated everything that people are fighting for today, which had already become a reality within his studio. I think Camus said it best: ‘The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.’”

Steven Arnold: Theophanies is on view 11 August – 24 September, at Fahey/Klein Gallery in Los Angeles. Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on photography.

Credits

Photography Steven Arnold, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles.