“Ugly is attractive, ugly is exciting. Maybe because it is newer,” said Miuccia Prada in a much quoted 2013 interview in T magazine. When it comes to shoes however, while ugliness may be attractive, and it may be exciting, it is often also about being old. It’s about wearing a shoe that will provoke your dad, who has read an article in the Sunday Styles section, to ask you “Am I ‘trendy’ now?” as he proudly holds up his Birkenstock, stained with mud from Woodstock, for inspection.

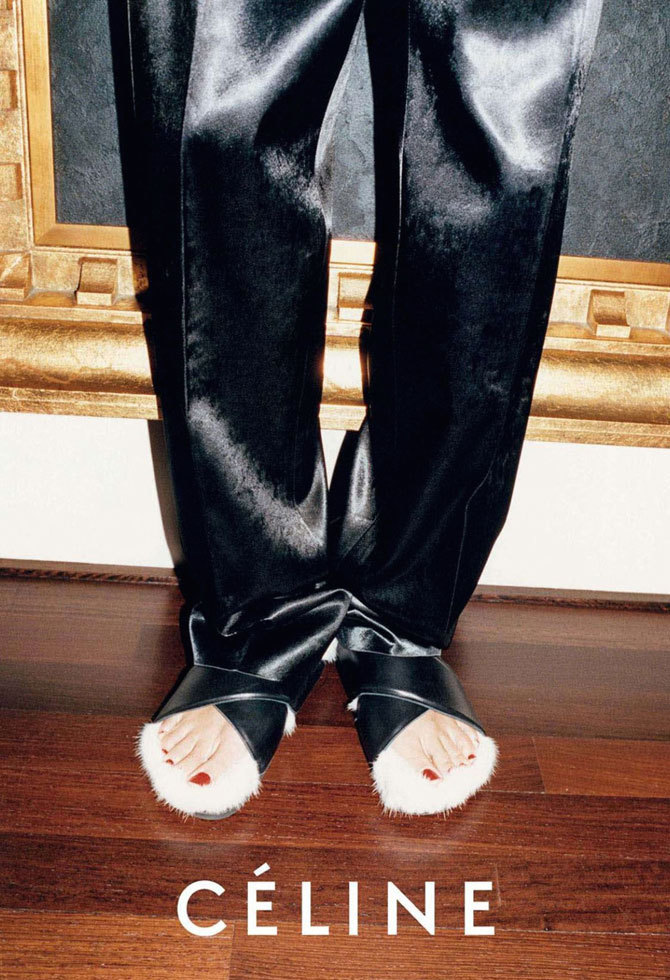

Since Phoebe Philo sent a mink-lined version of the Birkenstock Arizona down the runway during her spring/summer 13 Céline show, much ink has been spilled over the shockingness of the fashion world’s embrace of the Birkenstock, a shoe which Rebecca Mead recently traced from 18th-century Germany to present-day Brooklyn in a 5000-word piece for the New Yorker. The year before that, we had seen the beginnings of a pool slide renaissance. While Phoebe was creating the “Furkenstock” in Paris, in London, Christopher Kane had already figured out the perfect way to shake up his sugary collection of spring/summer 12 ready-to-wear: high fashion sports slides. “An ultra-high heel, especially with a mini skirt just looks so old now,” Kane said. His rubber-soled brocade sandals were a bejeweled throwback to the shoes you wore in the shower at summer camp.

Add to this list Tevas — references to which have appeared in collections by Prada, Patrik Ervell, Bottega Veneta, Lanvin and Opening Ceremony (now in its second season of collaboration with the brand) — and it’s a fashion fact: we can’t say no to a functional, sporty shoe. Almost anything that looks like it might be podiatrist-approved. But why? And why this sudden rash of revivals now? And how does this impact the non-Style.com-reading world at large? And, most pressingly, is the arrival of the high fashion flip-flop, as seen on the runway at Vuitton and Dior last week, a sign of the impending apocalypse or the beginning or another wave of ugly functional shoe mania. Should we all buy stock in Havaianas now?

For answers about fashion’s fascination with ugliness, we can look, as always to Miuccia Prada, and her former employee Jonathan Anderson. Both have been grilled extensively on the topic.”The investigation of ugliness is, to me, more interesting than the bourgeois idea of beauty,” Prada has said. “And why? Because ugly is human. It touches the bad and the dirty side of people.” Prada was one of the first designers to present oddly familiar, inelegant sporty footwear on the runway. In 1998, she debuted a nylon-strap sandal that appealed strongly to anyone who had ever worn and enjoyed a Teva. “I was very much criticized for inventing the trashy and the ugly,” said Miuccia.

By 2010, however, a shift had occurred. In her review of Prada’s fall/winter 10 collection, Cathy Horyn wrote, “Some of the outfits almost dared you to call them ugly. But the methods of examination have begun to feel dated.”

Miuccia’s rebellion against the constraints of Milanese “good taste” in the 90s (including her Teva 2.0) paved the way for a new generation of designers who were ready to explore “bad taste” straight out of the gate. Take Jonathan “J.W.” Anderson, Prada’s former visual merchandiser, who told The Independent in 2012, “When you find something really new, I always find it’s really ugly because your eye isn’t used to it.” Or Christopher Kane, pioneer of the high-fashion pool slide, who claims “there’s no such thing as bad taste.” Has Miuccia Prada’s boundary breaking created a post-taste fashion world? She’s certainly helped create a world in which a fashion editor can proudly wax lyrical about a shoe with a “squishy cork footbed” and “roomy toe box.”

But the real question is this: If ugly shoes come in two kinds — the theatrical, which sacrifices function for form (think: the McQueen “Armadillo”), and the quasi-orthopedic — why does our current obsession with ugly footwear center on the second kind?

The shoe from the wellness world of ugliness — the shoe which references sportswear and the medically prescribed — has a certain uncanniness. It harks back to the footwear of family vacations (the Teva), the school gym (the slider), or your former-hippie relatives (the Birkenstock). Where the OTT ugly shoe might distort familiar proportions to the point of obscurity, the practical ugly shoe gives us something we at least partly recognize. It is uncanny, in the Freudian sense. So what would Freud say about our fascination with a Vuitton flip-flop?

The Vuitton flip-flop has a thick-soled shape similar to that of a FitFlop but it is not a FitFlop. It was designed by Fabrizio Viti, made to be worn with crocodile-skin biker jackets and crepe pants in Palm Springs, and will probably cost many, many times more. It is both familiar and unfamiliar. And because of that, according to Freud, it both repels and attracts us — which is a psychic situation ripe for obsession.

There is also the question of comfort. Fashion historian Valerie Steele, in a discussion about ugly footwear with SHOWStudio’s Lou Stoppard last year, said of Céline’s furry Birks: “maybe [Phoebe Philo] was intending them as a funny sort of rejoinder to all of these sickening high uncomfortable heels that were going on around then.”

Steele’s comment acknowledges the obvious USP of many ugly practical shoes: arch support. It’s easy to knock a Croc before you put one on. But with your instep cushioned by a springy cloud of foam, you no longer care that you look like Mario Batali. (Crocs, incidentally had a moment last summer too, when they could be spotted on off-duty fashion professionals in Fire Island.)

Steele also points out that this desire for comfort is a reaction to a different strain of fashion. While a pump with a platform might say “I go to clubs with velvet ropes outside on Saturday nights.” The inelegant but comfortable shoe says “I know who Phoebe Philo is, I read books and I like Georgia O’Keefe.”

The obvious ugliness of the practical shoe is, in Steele’s words, “like a secret masonic handshake” between insiders. It is witty. And wearing a riff on a Teva or Birkenstock or FitFlop is the subtlest kind of fashion in-joke. It means you can dip your toe in the waters of eccentricity without having to wear an entire ensemble from Rei Kawakubo’s “lumps and bumps” collection.

Interestingly, though, the Céline “Birkenstock” also did wonders for the sale of real Birkenstocks. And high-fashion sliders fueled a craze for the very adidas sandals, available in sports stores nationwide, which they aesthetically trumped. It’s all part of that trickle-down effect, from runway to mass market, well noted in fashion theory. The Nike pool shoes we wore last summer may have come from a Foot Locker, but they were also an outer ripple from the initial shock of Phoebe Philo and Christopher Kane’s 2013 and 2012 collections. Or, in the words of Miranda Priestly in The Devil Wears Prada, they were “filtered down through the department stores and then trickled on down into some tragic Casual Corner where you, no doubt, fished it out of some clearance bin.”

Our fascination with the inelegant shoes of decades past is a perfect illustration of fashion’s cyclical nature — a cycle which is powered by those rare designers who can make us rethink our notions of ugliness and beauty. So what will it take to move fashion forward for spring/summer 16? A Miu Miu Dansko clog? A Balenciaga five-toe running shoe? Dries Van Noten MBTs? A Marc Jacobs SnUgg? Here’s hoping.

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson