This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Earthrise Issue, no. 368, Summer 2022. Order your copy here.

The Kogi are an Inidgenous group of people that live in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains in northern Colombia.

Living in harmony with the land, their belief is based around Aluna ‘The Great Mother’, and an understanding of the Earth as a living being, and humanity as its children. Faced with the rapidly increasing ecological destruction of our planet, they have been playing an active role as ‘Elder Brother’ to warn the world of the modern-day devastation of resources by ‘Younger Brother’.

They voiced these warnings in 1990, with the documentary From the Heart of The World – The Elder Brother’s Warning, and subsequently in 2012, realising that the importance of the message was still not grasped, with the sequel Aluna. In revealing the traditions which have kept them alive all these centuries, they hope to share their planetary sciences and convince the rest of the world to take responsibility for the environmental damage caused by its actions.

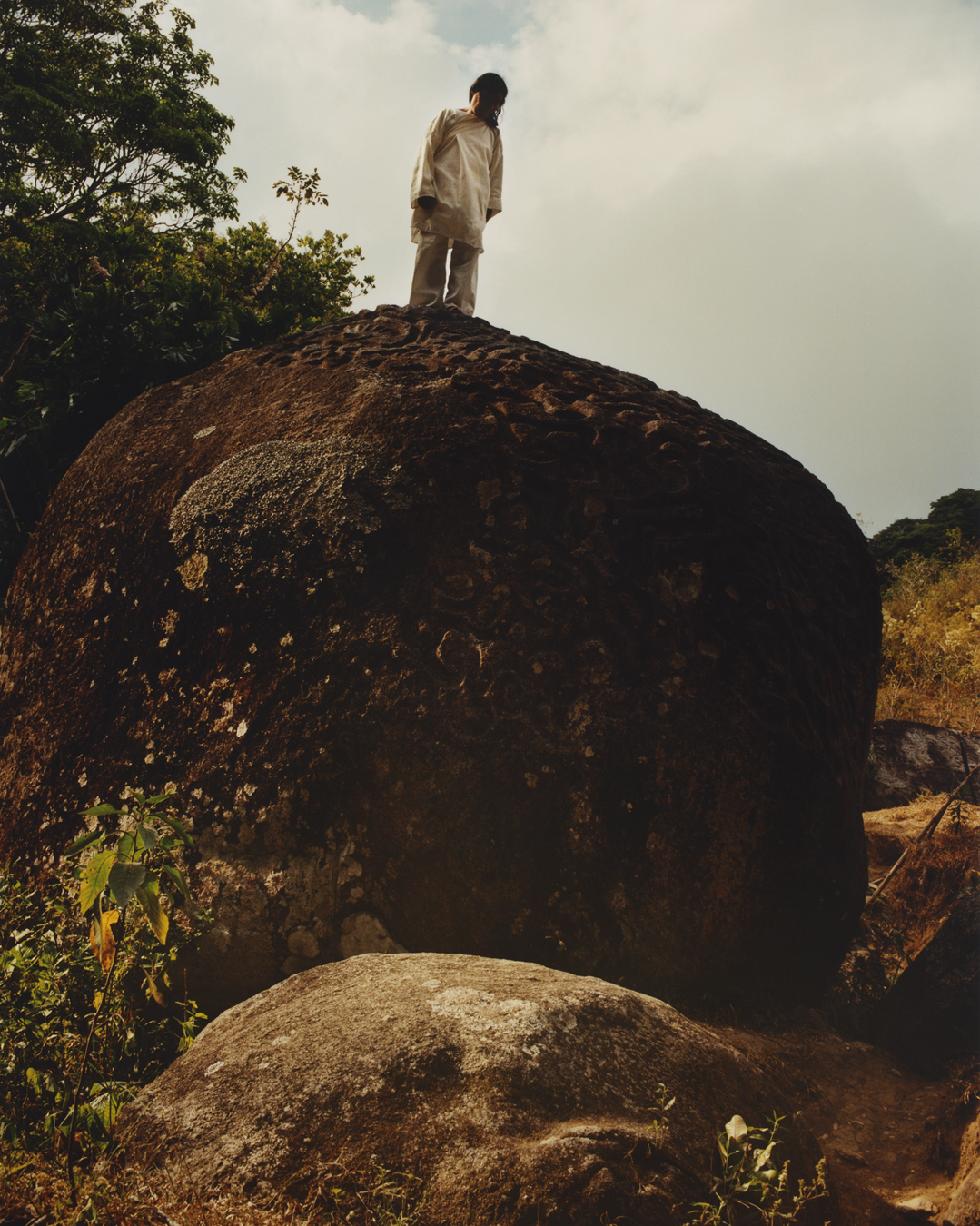

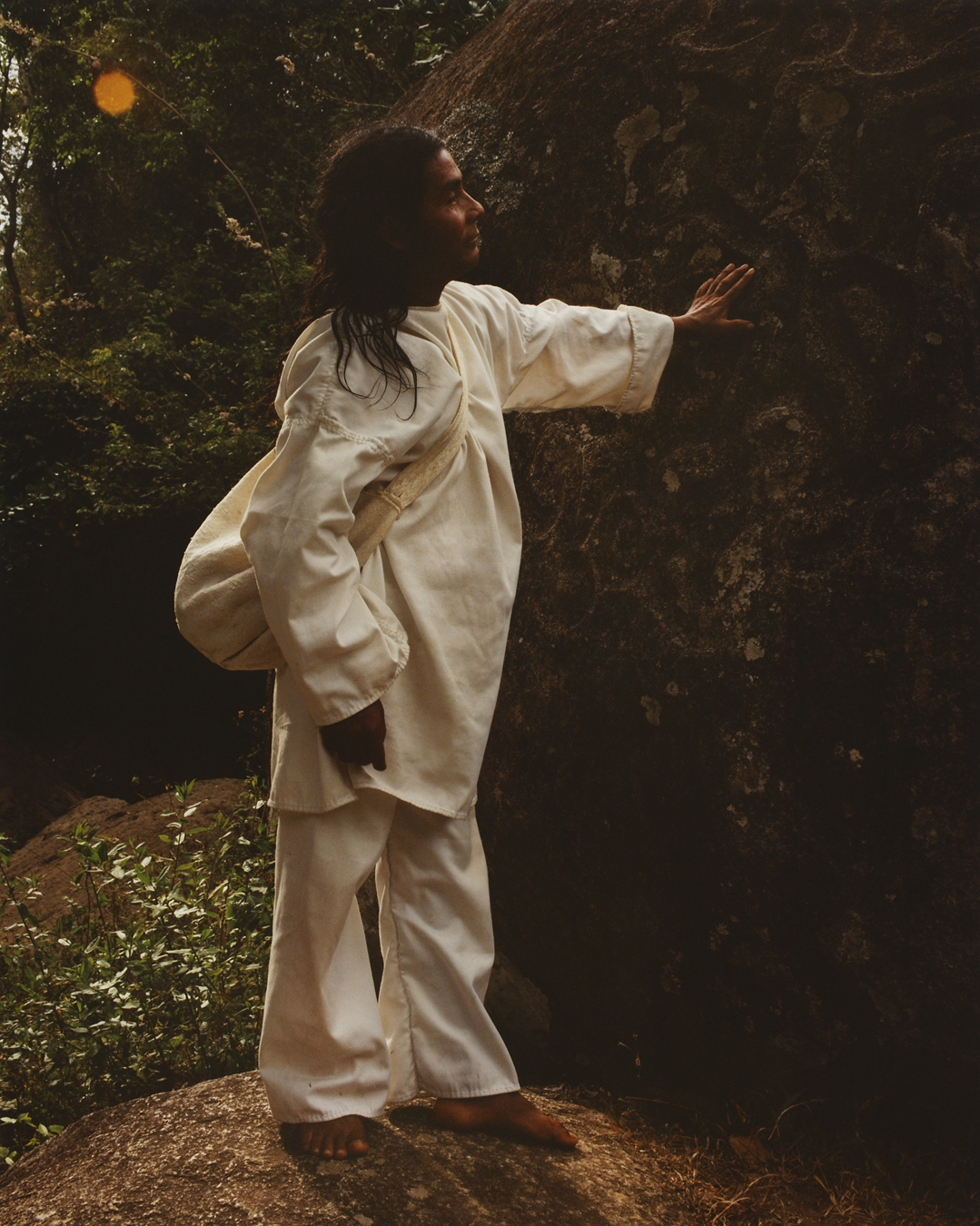

Photographer Théo de Gueltzl has spent time with many of the various Indigenous peoples of South America, and most recently with the Kogi. This photo essay gives a unique insight into their society and relationship with nature. Dressed in pure white cotton clothing, we see them pictured in front of the thatched huts in which they live, and on top of the Donama – ancient carved boulders central to their pilgrimages and rituals.

“The Kogi’s cosmogony is linked to their environment,” Théo says. “They feel that the way the Western world wants to impose itself on the rest of the world is terrible: it breaks the balance that exists between nature and us. They see a lot of direct reactions from nature in their environment. After the creation of a dam, or after the building of a big port in places that are sacred to them, they feel the ill effects.”

“What happens to the Earth is what happens to us. And, what happens to us is what happens to the Earth.” Benjamin Gil Gil

The Kogi believe that every element of nature has a spirit and the land is connected by ‘threads’. Whether it be the roads that weave through the jungle, or the stories they tell as they walk them. All these threads join the world together on a spiritual plane.

“They spend their life walking up and down the mountain, which is what they call ‘threading’ the land. The women spend their time threading bags and clothes with the cotton they get from the trees in the mountains. And then men thread their stories, while walking up and down the mountain,” Théo explains.

In an effort to spread this message, Kogi brothers Benjamin and Eliseo Gil Gil, are writing a book with the purpose of further strengthening their traditional knowledge. Not only to share the importance of helping Mother Earth with the rest of the world, but also to give other Kogi people in the mountains an opportunity to access and visualise their law of origin. As Benjamin explains, “What happens to the Earth is what happens to us. And what happens to us is what happens to the Earth.”

To find out more about the Kogi we spoke to Santiago Giraldo, who, for the last 22 years has been working as an anthropologist in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, to preserve the cultural and natural heritage of the region through research conservation, and community development. He is the CEO of the Fundación ProSierra Nevada de Santa Marta and Director for Latin America of the Global Heritage Fund.

Can you tell us what kind of relationship you have with the Kogi?

I know some of the Kogi population in the State of Magdalena and I have been friends with some of them for the last 22 years. I have initiated multiple community development projects with them, building schools, bridges, health posts, and solar microgrid installation, and we are in frequent communication; especially with the inhabitants of the Buritaca river basin due to my work as an anthropologist and archaeologist in Teyuna-Ciudad Perdida.

What can you tell us about the Donama stones featured in these images?

The first reference and photos of the Donama stones date back to 1921/1922 when John Alden Mason, curator of the Chicago Field Museum, visited the Santa Marta area to do research. The stone is a large petroglyph, associated with a Tairona habitation site near the present-day village of Bonda. What the site meant for these ancient populations is a relative mystery, although there are multiple interpretations.

Can you tell us what challenges the Kogi community are facing today?

The Kogi, like any other Indigenous group today, face multiple challenges. It is not easy to refer to the community as a whole since they inhabit a fairly large area and have internal political divisions, as in any society. This makes the different leaders think in diverse ways about what the priorities are. From an external point of view, I consider that the most difficult challenges are poverty, and the lack of access to decent education and health services.

The Kogi are interacting more often with the modern world, how do you see that affecting them?

The Indigenous population of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta has been in contact with the non-Indigenous population since the beginning of the 16th century, and before that with many other Indigenous groups that surrounded them, so they do not live, nor have they ever lived isolated from other societies. Their lifestyle reflects the time we live in and they have autonomy over the level of interaction – or lack thereof – that they want to have with the non-Indigenous world and with other Indigenous people who are different to them, so there is a wide range of attitudes between young men and women, adults, and seniors. How does that affect them? I think it’s a slightly paternalistic position. I prefer to think that as a society which has managed to survive for so many years, it has enough tools to decide upon and manage its interaction with the rest of the Colombian society autonomously.

What do you think about the preservation of ancestral communities and cultures? And how can we ensure its preservation in the case of the Kogi?

The Kogi should be the ones who decide what to do with their future. They can decide what – or indeed whether – they wish to change. My role has been to focus on developing joint projects with them, aimed at improving healthcare, education and family income. These projects are designed when requested by the authorities in each village, so, in general, the work is based on what each village specifically wants. On the other hand, I think that it is normally impossible to preserve ancestral cultures from the outside: all societies change, either a lot or a little, slowly or quickly, but they change due to historical events and situations they must face up to. Therefore, trying to “preserve” a society and attempting to prevent change is futile, and pretending that a person, institution or the government can do so reinforces that paternalism and assumes a position of unbearable pedantry. i.e. thinking that some foreign or local white guys are going to ensure that an “ancestral” society maintains its norms and customs without fail and that they know what is best or worst for the Indigenous population.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more from the new issue.

Credits

Photography Théo de Gueltzl

Special thanks to Mamo Manuel, Mamo Luis, Eliseo Gil Gil, Benjamin Gil Gil, Santiago Lourido, Natalie di Sabatino, Camilo George Jimeno, Sandy McLennan, Lorenzo Perafan and Arregoces Coronado Zarabata