Tom Sachs’ story originally appeared in i-D’s The New Worldwi-De Issue, no. 363, Summer 2021. Order your copy here.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Printed material has always been part of your work, over the years you’ve done so many amazing artist books and have almost reinvented the use of print as an artistic medium. So maybe we should start there, because the work in this issue of i-D is almost like a printed exhibition.

Tom Sachs: A zine is a homemade magazine, I’ve been making them since high school. About a decade ago I made a decision to make a publication for every art show I ever did, whether that was a fancy museum catalogue or something I did myself on a photocopier. It’s a ritual to make a zine. And I cherish the zines other artists give me, because you can’t always afford the space for a sculpture or a paint-ing, but there’s always room on a bookshelf.

I remember the show at Thaddaeus Ropac where you issued every guest a Swiss passport.

Those passports were zines, effectively. They were one of a kind zines. A passport is a very important book and we were trying to make it less important. We wanted to lower those barriers. The Swiss passport is a status symbol, not only of national identity but also phony neutrality and freedom to travel anywhere in the world. Borders are artificial, created by governments and the corporations who control them.

The Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky always said that we live in an age bereft of rituals. And I think rituals keep us from forget-ting what must not be forgotten. But ritual is also a daily practice. I read every morning and that’s a type of ritual, even if it is rela-tively banal. I walk in the park every day, and I buy a book every day. Those are my rituals. What are yours?

I’d love a personal answer before we talk about the rituals of work and exhibitions. On a good day I don’t look at my phone first thing in the morning. I don’t look at email, Instagram, text messages, WhatsApp, Twitter or Discord. I go and make a chawan, a tea bowl, so the first thing I do is touch clay, prioritise mental output before input. You have the greatest connection to your subconscious mind right when you wake up. That’s the moment where things don’t make sense in a logical, intellectual way. I always try to draw, make, or do something that’s output before I start the day, because the day will eventually find me. The emails will eventually track me down and crush my spirit, by making demands of my attention that would be better served through making sculpture.

The power of my art comes from my intuition. There’s so much information going around in the world that I have to be very disciplined each morning to find my own thoughts within myself. By connecting first thing in the morning with my subconscious and creating some-thing, I’m cultivating my mind more, and strengthening my intuition.

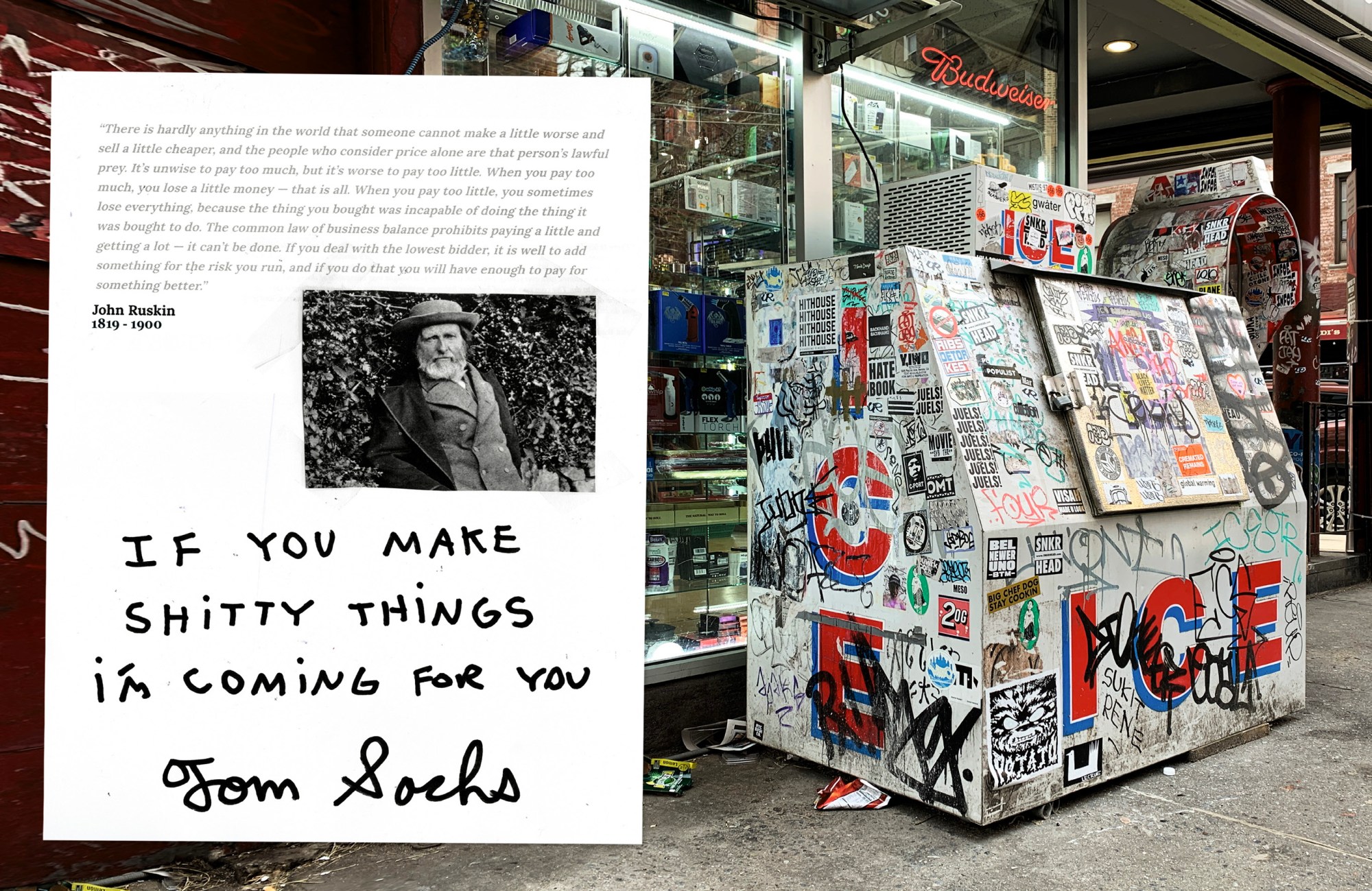

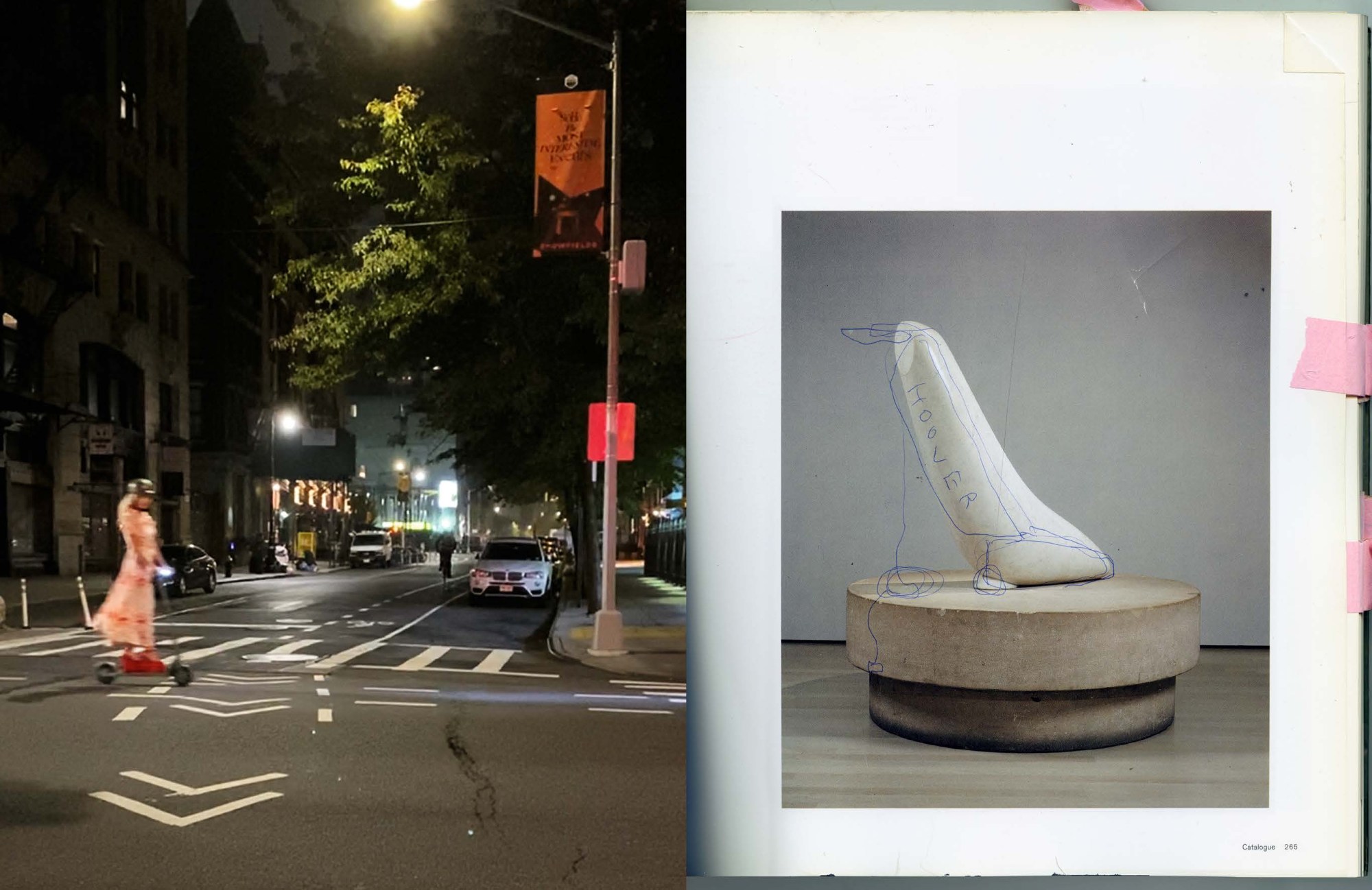

The ritual that’s most interesting to me is the ritual of the streets, because the streets are always where I find my inspiration. The first image that I have of my wife is on the street with her bulldog. I find things in dumpsters on the street. I collect images on my camera in the street. The idea of the street extends to the bodega and ultimately the museum. Whether it’s a surveillance camera stack, a garbage can, a laundry basket, a bottle rack, or a Brancusi, it’s all the street to me.

There is really a fabulous new book, which I read in German during the first lockdown, by Byung-Chul Han, and the book is called The Disappearance Of Rituals. And he talks about the fact that we have a lot of communication now, we live in an age of more and more information, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that we have more memory, and that maybe amnesia is somewhere at the core of the digital age. We have a lot of communication and not a lot of community. He talks about this 21st century crisis of community which produces a narcissistic idea of authenticity and a mass turning inward, but he talks also about us as individuals living in atomised society, and the importance of rituals in that society, and to paraphrase him, the disappearance of ritu-als is a means of diagnosing the pathology of the present. It’s only through ritual that we can create our communities, because rituals create something symbolic between members of this community that isn’t commodified.

There’s almost a melancholia that I experience in the city now. I used to love walking down Lafayette Street or Canal Street and seeing all these unique shops and artist spaces, but we’ve seen nearly every amazing mom and pop shop disappear. There’s been a global loss of hardware stores and McDonald’s has replaced every little diner. There’s this loss of identity in the city, a loss of individual culture. But some places are still holding on, fighting; that’s the power of walking, or taking the subway, whether you’re in New York, or London or Tokyo, it can connect you with what is really going on in the city. To travel by plane is sin. By foot, virtue.

Covid sucked the life out of the street. We connect now with computers. Zines have, for better or worse, been replaced with Instagram. We find community there but it’s so algorithmically refined that it doesn’t demand engagement. It simply provides yet also connects, and that’s an upgrade. My Discord @tomsachs has many discrete channels for discussion on topics ranging from rockets to repair, to art and to existence. It’s a place, like the street, where people meet.

Let’s talk about the exhibition you have coming up, then, that relates to this work in this magazine. I wanted to ask about what you want to prepare for this show of pure sculpture, because you’ve always oscillated in a way, I feel, between 2D and 3D. One of your really early works I remember was when you used duct tape to recreate Mondrians on pieces of plywood. It wasn’t so much about appropriation, but about repetition, and difference, and a lot of the work exists in the space between 2D and 3D also.

I think of those Mondrians as sculptures. They’re like sculptures of Mondrian paintings. I’ve always done both painting and sculpture, because, as Germano Celant said, “It’s an expression of my insecurity, I want to show that I want to do everything.” Last fall I did a show at Acquavella Galleries of just paintings, I called it Handmade Paintings. I just tried it as an experiment. I thought this was a very successful show of paintings because they didn’t rely on the aspect of my painting that wasn’t good enough to be represented in a sculpture. Or, that I didn’t have to rely on something in painting to take care of something that I wasn’t able to represent in a sculpture, or vice versa. The painting and sculpture weren’t there to help each other, maybe, is a better way of saying it. I feel like an adult.

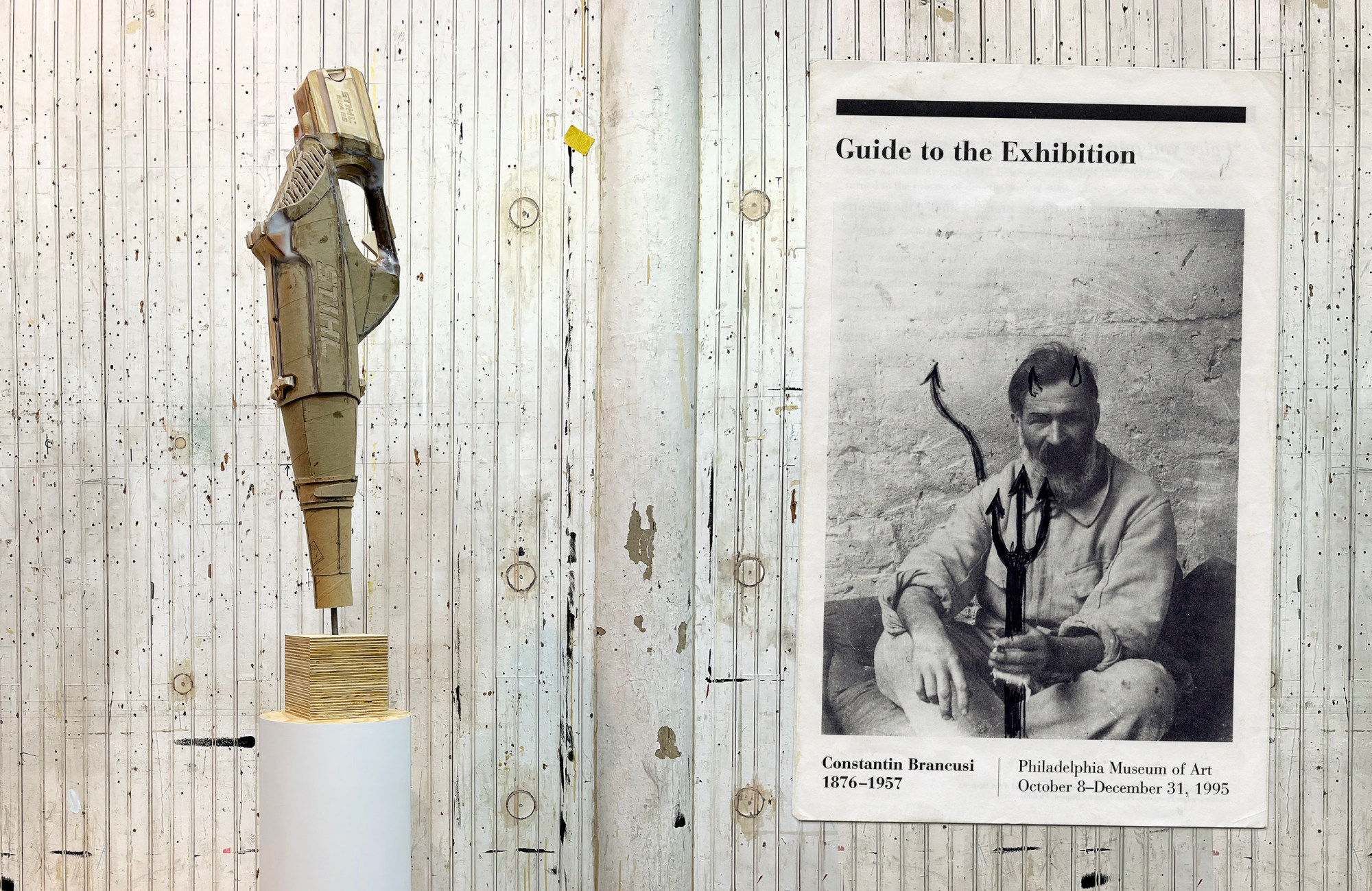

This show in London will be my first only sculpture show. There’s nothing on the walls. I was able to really connect with my youth, with studying Brancusi and David Smith and Julio Gonzalez and Etruscan and African art, and really trying to get into formal issues of sculpture. My dream is that I’m going to eventually be able to do an abstract sculpture show.

I haven’t seen the latest Paris show in person but I have seen images online. It’s interesting to think about the way the plinth plays an important role in that show. I was thinking about Barbara Hepworth’s 1968 retrospective at the Tate, and the way she used concrete plinths in that, or the way she positioned works directly on the floor, really rejecting the rules of displaying sculpture.

I don’t think I have the confidence to display a work directly on the floor, I need to bring it up to eye level. But if you bring it up to eye level on a regular plinth – like a plywood cube – the plinth is bigger than the sculpture. And I remember seeing a show of some amazing sculptures that were displayed on these plywood boxes, and I thought it was so stupid because the pedestals were taking up more space and value than the sculptures.

So I started trying to work out a form that would be complementary to the sculpture. That’s what Brancusi did, he made the base as important as the sculpture itself, he made it another space to explore texture and colour and form, and some of the shapes of the plinths are taken directly from Brancusi, but others from industrial shapes. Contrast brings attention to the form.

I wanted to ask about your relationship with another artist of that generation, Marcel Duchamp, and the problems of the readymade, and how you choose an object, but this question has also got me thinking about something else. I spoke a few days ago to Honey Dijon, and we talked about fashion designers who work with recycling and upcycling. And there’s almost a connection now between the readymade and upcycling, these ideas of sustainability, recycling. I don’t think these were concerns of Duchamp, but I think now we can maybe see these connections.

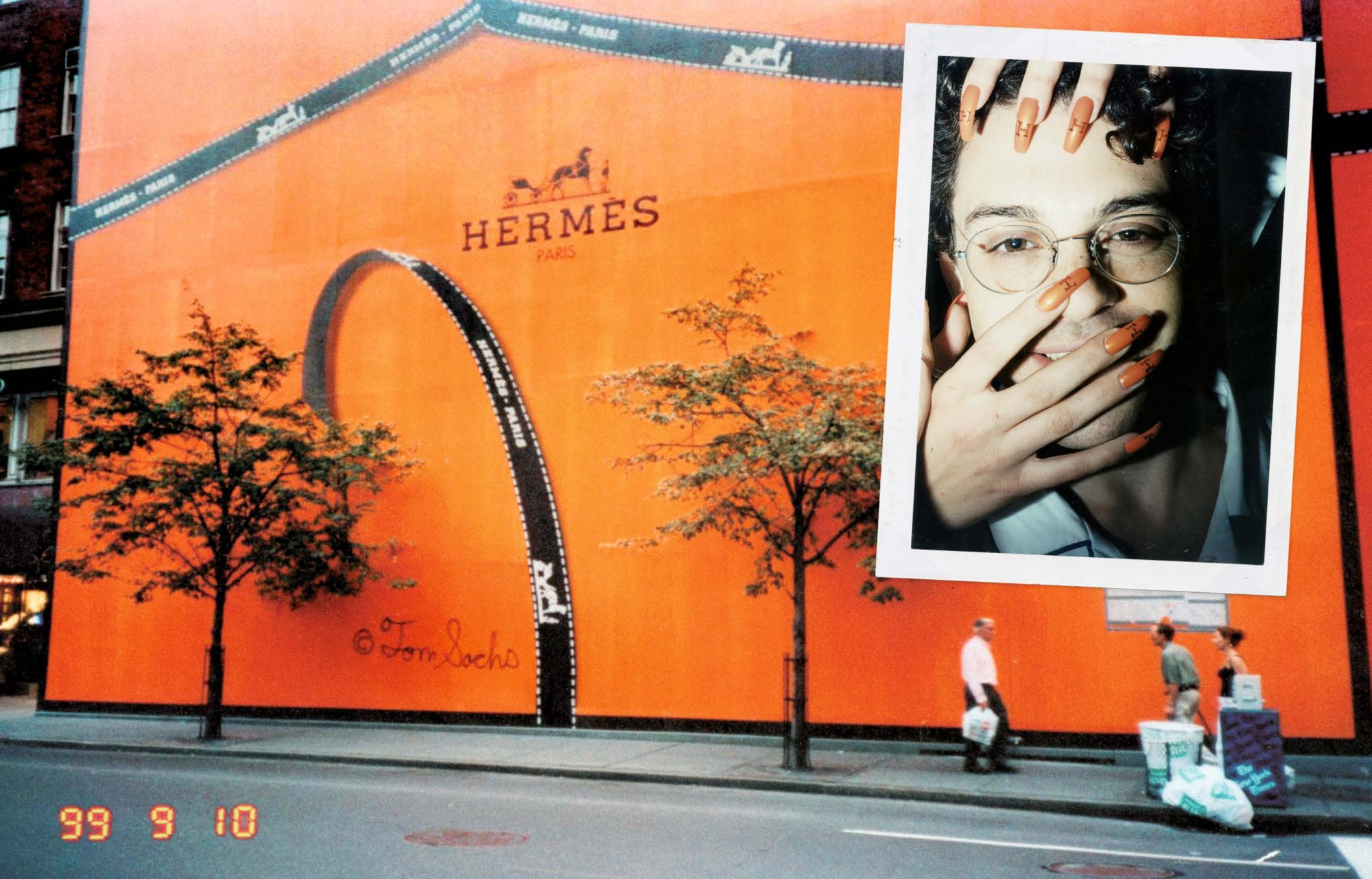

In a way Duchamp is my parent, my ancestor, and the confidence of Duchamp just to exclude everything else and say, “This is art” is not a casual thing. These objects are very well selected, and hopefully I’ve inherited some of that criticality because I’ve been working very hard at it. To go back to the Mondrian works, it really comes from a sympathetic magic; I wanted a Mondrian and couldn’t afford one, so I made my own. I wanted a Swiss passport and couldn’t deal with the headache of becoming Swiss, so I did that show. Lee Scratch Perry became Swiss. I always thought it was amazing Jamaica’s greatest visionary has Swiss as part of his national identity. He’s Jamaican and Swiss, how many people can say that?

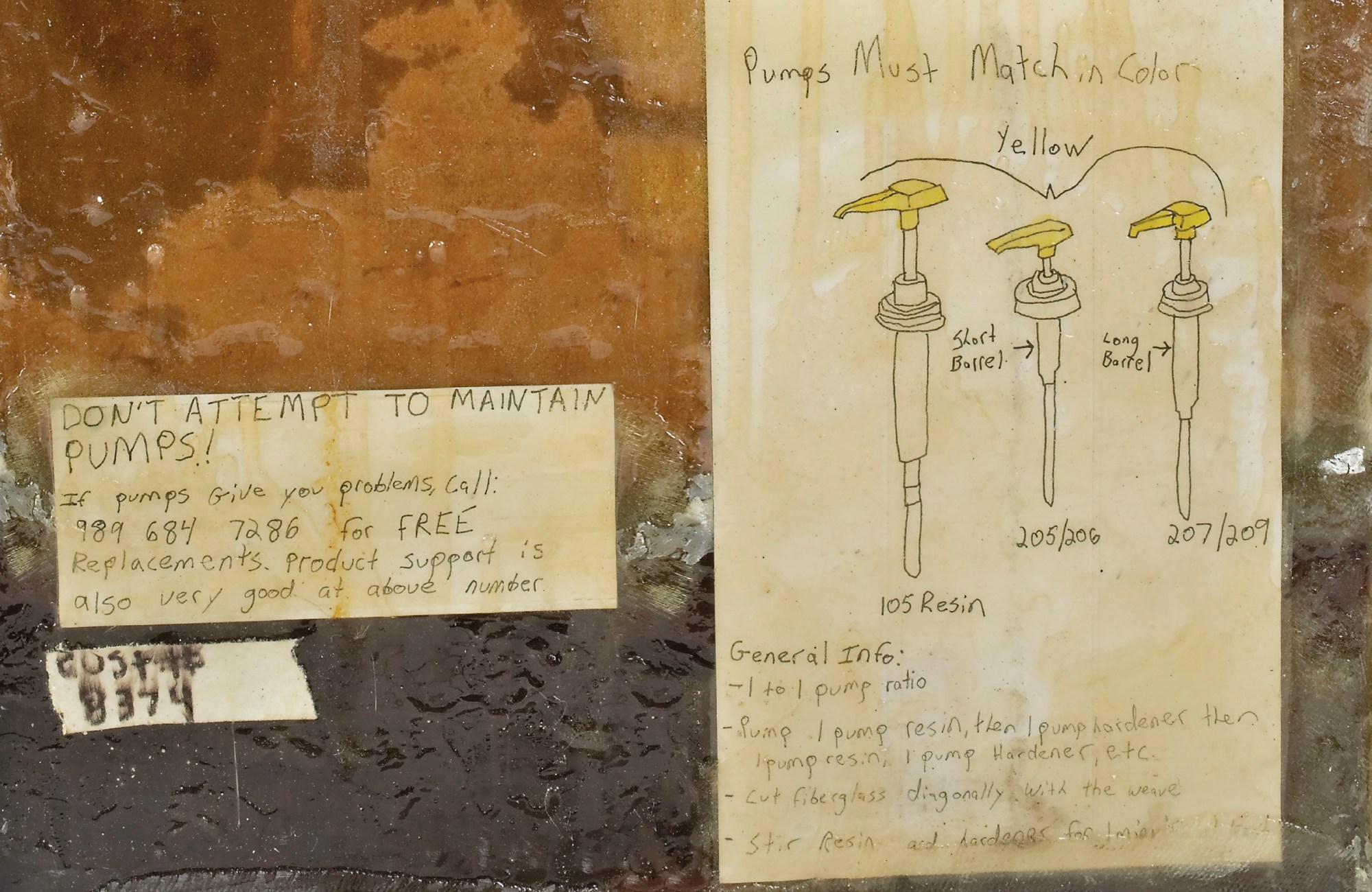

Recycling is important because all these materials come from the dumpster. When I pull the plywood out of the dumpster and cut it, and use it, it’s not recycling, that’s repurposing, a higher level of sustain-ability. Recycling is at the bottom of the hierarchy. Reuse is much higher, durability more than anything is the most important thing because making something last is the highest standard of excellence. It’s also the most ecologically sound. The wood that has the plywood cut edge, as an example, is evidence that it was recycled, or that it had a prior life. That prior life’s important biologically and culturally.

One thing I wanted to talk about too was the links to brands in your sculptures. I was curious about this question of appro-priation, and what is a source and what is a copy. And what is fascinating in your work is that the process also gets inverted, and that you work with brands to reach millions of people who otherwise would not see your exhibitions. And we do need to find new forms of collation and dissemination for art. I have done a lot of studio visits over the last couple of months over Zoom and there’s a lot of interest from younger artists in brands, brand-ing, and infiltrating the idea of a brand with collaboration. You have done this, and you did this very early.

I try not to collaborate too much anymore, with the exception of Nike, because it’s a lot of work and I need to stay focused on my own sculptures. But with Nike we’re able to do things that neither of us could do without the other, so that’s a true collaboration. It represents the values of my studio and it represents the values of Nike, and it’s a chance to make some lasting products. One of the things that’s most exciting to me is that these are not products that I’m making for Nike, but products that Nike is making for me and my team. Everything we make together is something for me and my community. I want to make things, whether those are sculptures or sneakers, that speak to me and to you and our friends. If it expands beyond that, and to art environments like muse-ums and galleries, that’s fine, but the origin must be for us.

One thing I think is that we need to liberate ourselves from short term-ism, especially in the sustainability debate, and we need to go beyond exhibitions, create longer duration projects, maybe gardens, or farms, and I know a lot of people working in farms at the moment. I think we all want our chairs, for example, to last 80 or 100 years, but why shouldn’t this be the same for a shoe?

Isamu Noguchi said: “Technology is the true development of old tradition”. It’s important to build on the past. Whether it’s a sculpture or a sneaker, innovate incrementally and only when necessary. We haven’t really done that many things with Nike in the past decade, but they’ve all built on the last thing we did. I think one of the problems is producing too much. We want to be an example of how you can get more done by doing less. We are careful, and take our time, and we take care of our shoes and our bodies and the planet.

Before we go we have to talk specifically about this body of work you have made for this issue of i-D, which will accompany the upcoming exhibition in London. Can you speak a bit about how you designed these magazine pages to accompany the show?

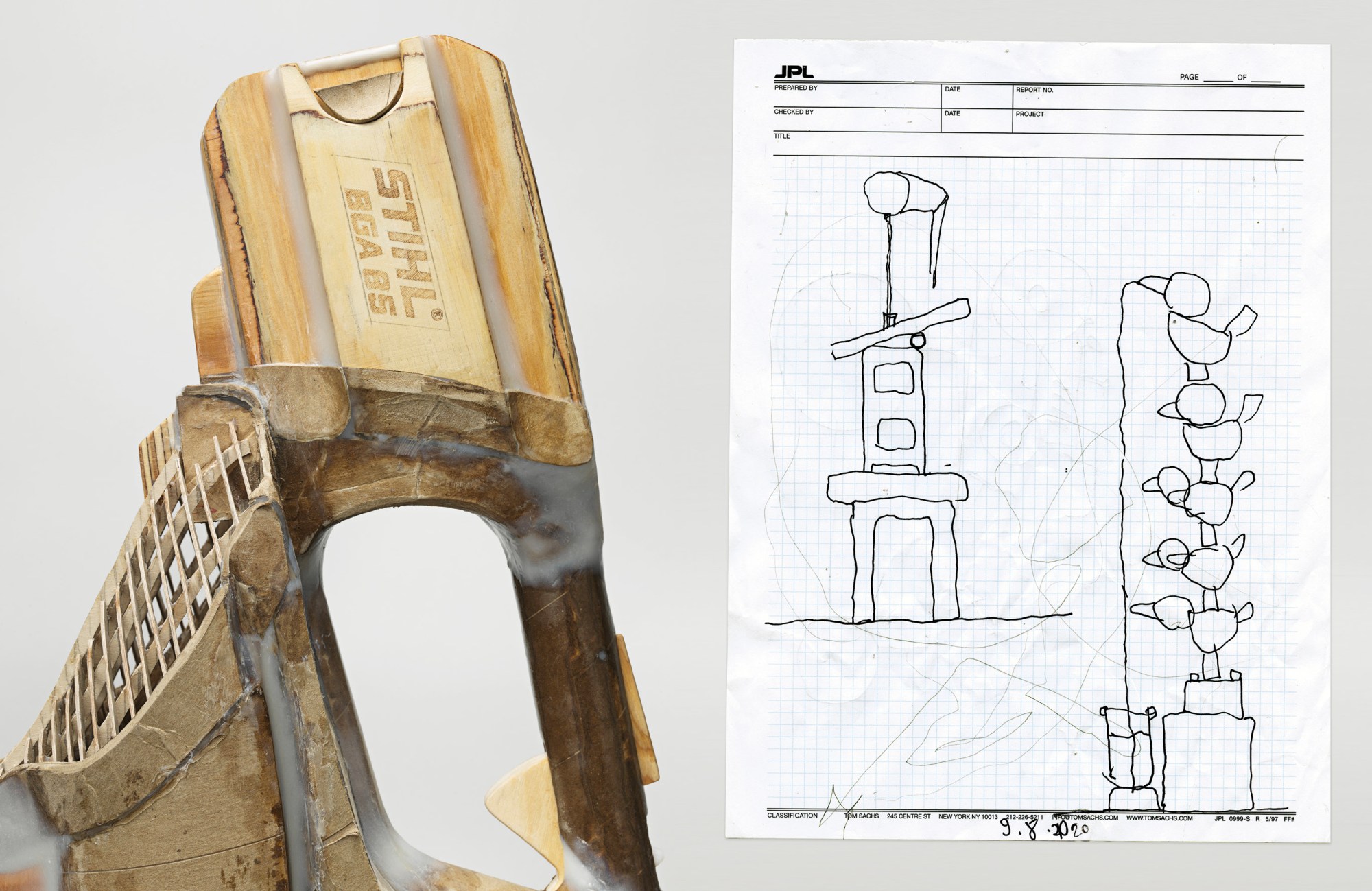

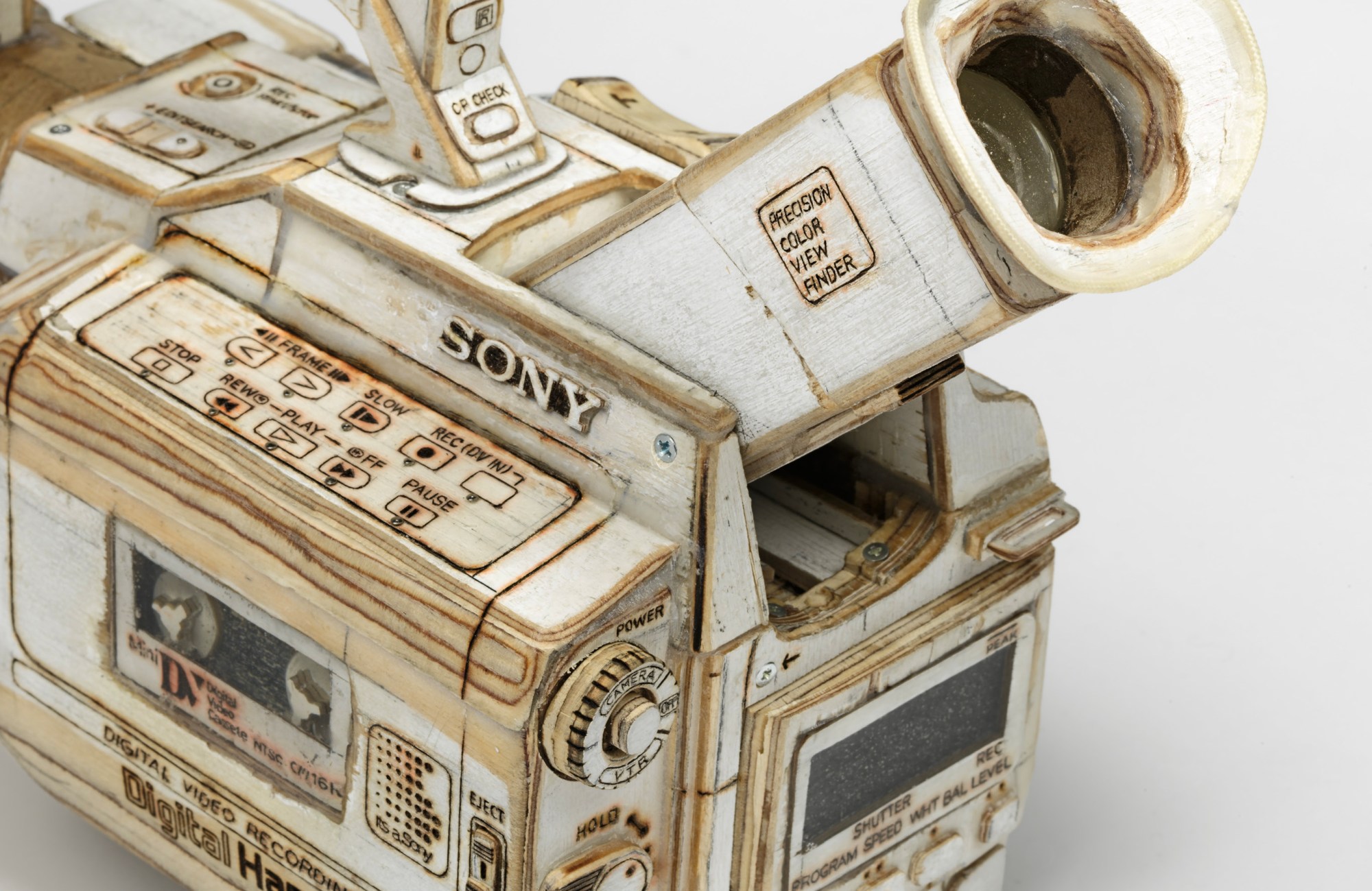

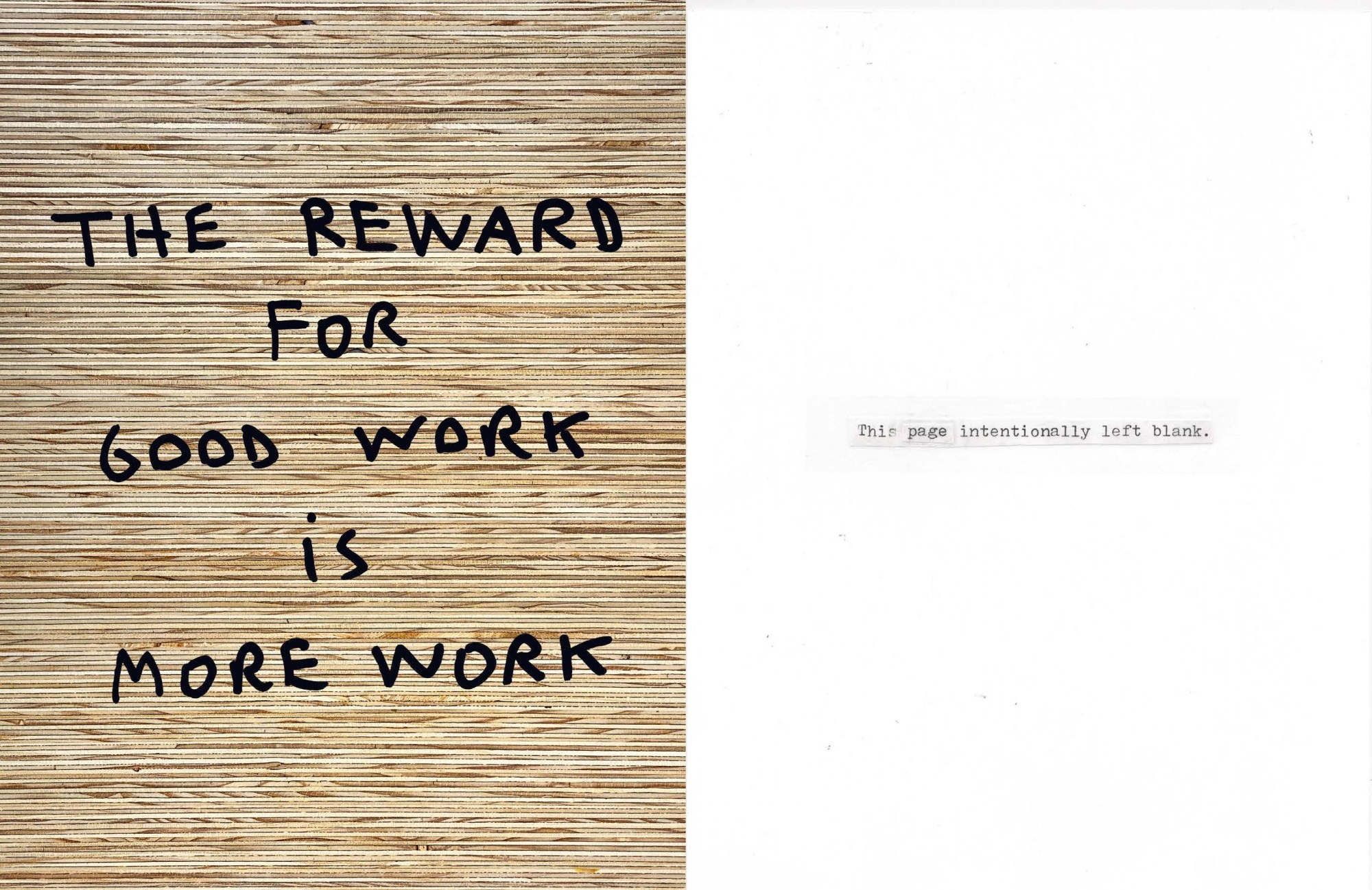

One thing I wanted was to make sure that everyone can see how terribly made these sculptures are. It’s important that people come and see my work up close and say things like: “Wow, it’s really terribly crafted, you can really see the evidence of how it was made”. To me it is the highest compliment. The iPhone has no evidence of it being made, everything is hidden. I could never make something that perfect, and Apple can never make something that’s as flawed and fucked up as one of my sculptures. I want the accompanying photo-graphs to be analogues of those sculptures.

These photos have qualities that I’m looking for in my sculpture. They show the creation, information, and the story of them being made. The one ritual that we didn’t talk about is the ritual of working, and of making sculpture, and I feel like everyday I have to make some-thing. Like a vampire who must drink blood every day, I must touch clay or cut wood.

And I think as always for this last question I’d like to ask you about your unrealised projects, and we’ve spoken about some before, but I’d love to finish on that.

Imagine a giant gallery in the shape of a human, and you enter through the door, and that’s the mouth, and then you go into the brain. Maybe inside the brain there are images and experiences of what’s going on inside; maybe it’s pornography, maybe it’s money, maybe it’s puppies; it’s the human mind as perverse and as loving and beautiful as it can be. You go through all the organs, the hearts, the lungs, and then at some point you’re either reborn through the vagina or you’re excreted through the ass. It’s an opportunity to explore all the different organs of the body. Each organ is a room. You’ll travel through the fingers and the hands and the feet and into the liver and the pancreas, and have windows coming out of the eyes. It would be an incredible opportunity to explore medicine. It might be linked to this other project – starting my own medical school and making myself the first student. I’ve been studying the body, it’d be good to put those together.

That could not be a better conclusion. Thank you so so much. It was exciting.

Thanks, Hans Ulrich. Thank you so much.

Credits

Photography Genevieve Hanson

Additional photography Tom Sachs, Serena Smith and Sam Ratanarat

Design Serena Smith and Tom Sachs