Louis Vuitton is a French fashion house, but under Virgil Abloh’s four-year tenure as its creative director of menswear, it also became a home to his community of like-minded artists. Yesterday’s AW22 show — the late designer’s eighth for the house — served as a poignant reminder of that. Quite literally, in fact. Before he died, Virgil conceived of a set where guests would enter through a sky-blue porch, the kind of quintessential suburban American dreamhouse facade, and find themselves in a sunset-hued skyscape, peering over a giant smoking chimney and into a fairytale-sized bedroom. For his first Louis Vuitton show, Virgil built a Yellow Brick Road, a cinematic reference so loaded that it commanded to be taken literally. Now, for his last show, he built a house, the kind that Dorothy clicks her red slippers to get back to. Despite his constant globe-trotting, never-ending scrolling and constant communication — the idea of a homecoming was clearly on his mind. And though Louis Vuitton may be associated with travel, any seasoned traveller —Virgil included — knows that the best part of any voyage is coming home.

To say that Virgil was simply a fashion designer would be like calling Louis Vuitton just another luggage manufacturer. It’s bigger, more symbolic than that. For decades, there have been designers that have pushed the parameters of what women could look like to extremes — and there are plenty of muses pinned to their imaginations as symbols of self-invention. Virgil, in hindsight, was doing that for men at Louis Vuitton — especially for men of colour. He was never a designer claiming to invent something new because there’s little that has not already been done. Instead, he sought to expand on the symbolism of preexisting clothes and their associations — sportswear, tailoring, logos and leather goods — and flip the connotations, offering new ideas of how men can express themselves through the way they dress, and how clothes can play a role in the life we see for ourselves.

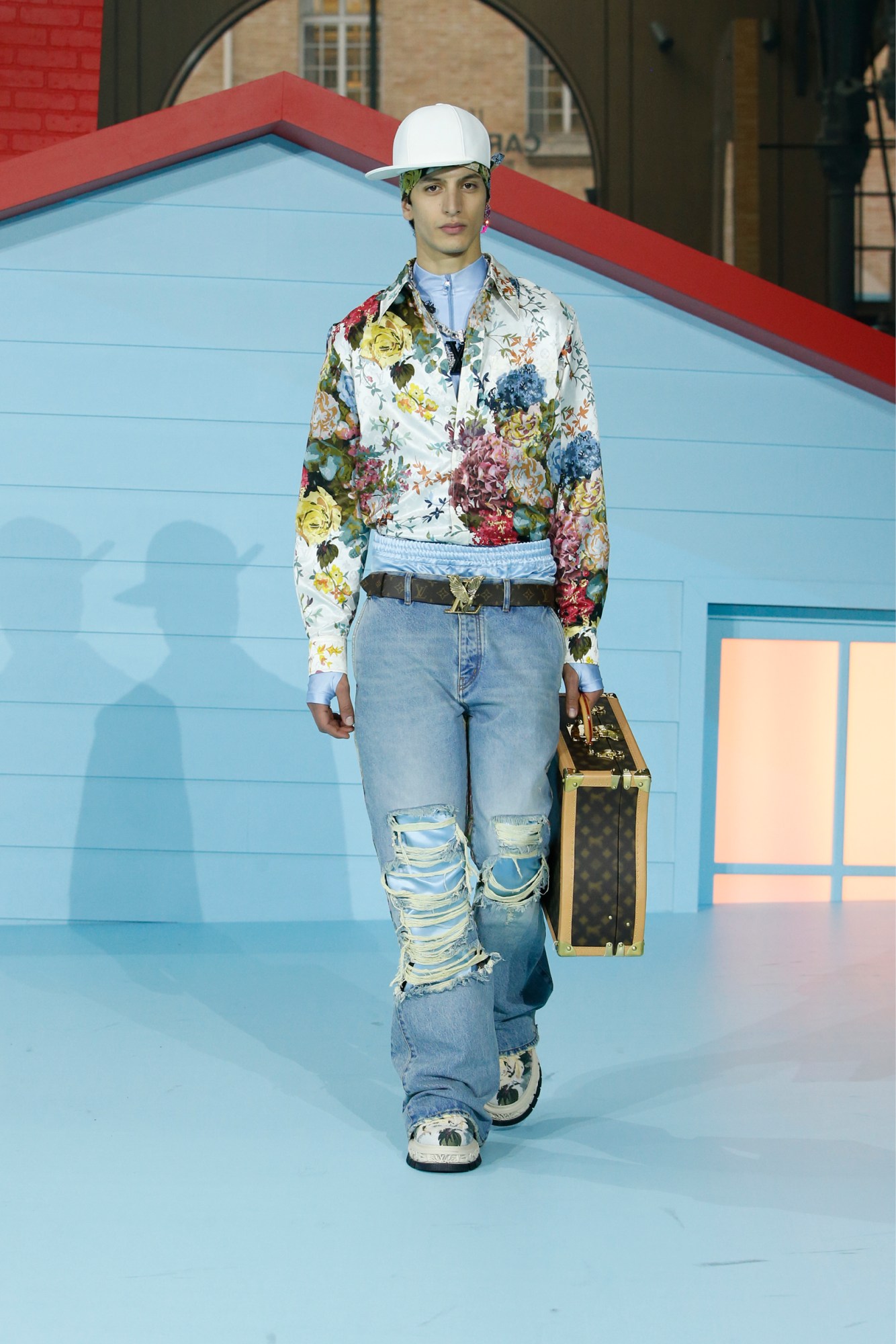

After all, why can’t a hoodie be made in luscious Medieval-style bucolic tapestries, fit for a red-carpet gala? Why can’t djellabas be rendered in beautiful damask silks and shown in Paris alongside the staples of Americana? Why can’t denim skatewear be transformed into bejewelled monograms, and tie-dyes appear as mottled shearlings? And who says that you can’t put your best foot forward in a pair of pristine Nike Air Force 1s? Virgil called it ‘Maintainamorphosis’, “the principle that ‘old’ ideas should be invigorated with value and presented alongside the ‘new,’ because both are equal in worth.” Dress codes, for him, were social and political ciphers that are far too often employed for division, and so he playful toyed with them as a way of ushering in change below the surface.

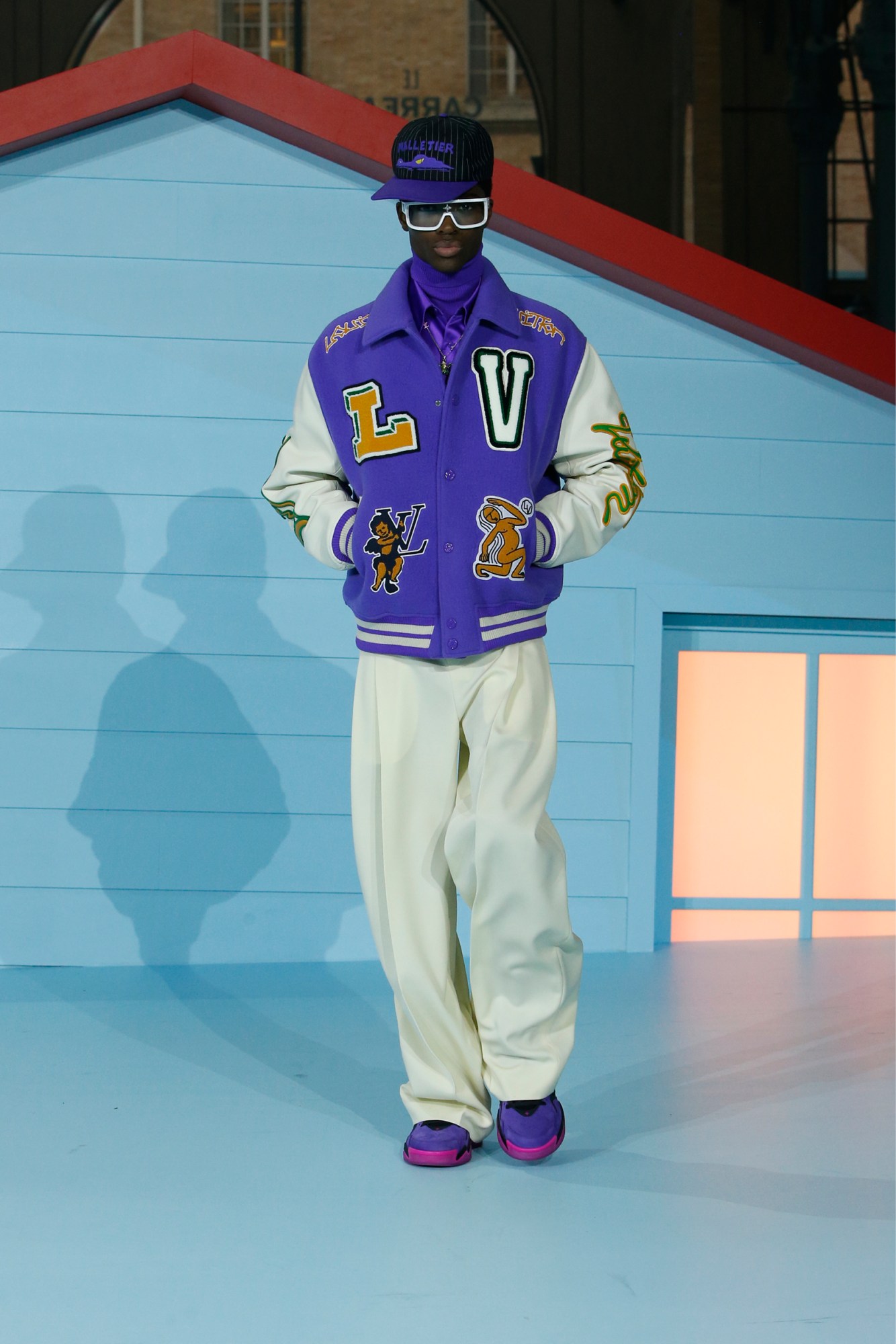

Louis Vuitton’s AW22 collection was half-designed by Virgil before his death, and completed by his devoted studio team, who took a bow after the show. They all wore violet T-shirts, which had one of the late designer’s beloved quotation-mark messages emblazoned across the back: “I have an idea…” And here was a collection full of them, so many that it’s impossible to describe one unanimous theme. Here were modern-day-dandy silk suits, whittled at the waist with slouchy cargo pants; workwear styles taken to new heights by extraordinary fabrics; graphic sportswear in plush velvets and pleated tulle skirts. Throughout, patches of childlike cartoons of clouds, cherubs, wizards and even the Grim Reaper appeared as badges of pride, and to finish, a breathtaking chorus of angelic-white looks with kite-like lace wings and bridal veils streaming from baseball caps. You got the sense that Virgil was pondering the notion of mortality and after-life, considering it through the unspoiled eyes of a young boy.

The clothes were brought to life by the contorting movements and wandering rhythms of 20 dancers and 67 models, who at one point filled the space, looked up to the skies and froze in stasis, almost like the life-size statues of his muses that can be found on the menswear floors of Louis Vuitton stores around the world. It was heightened by the dramatic soundtrack, composed by Tyler, the Creator, Arthur Verocai and Benji B, and performed by the Chineke! Orchestra, the first professional orchestra specifically celebrating diversity in classical music. Each musician sat on chairs with hand-painted epithets by Jim Joe, the street artist and one of the first people to visit the Louis Vuitton headquarters when Virgil arrived.

Ultimately, that’s what made this show so special. It was a celebration of Virgil, completed by his close-knit community of artists, collaborators and employees. When he first joined the French house, so much of the discourse surrounding the announcement focused on his beginnings in ‘streetwear’, a term that has been misused and racially-charged since becoming a buzzword. “In my game of inverted commas, streetwear is a community founded in subculture, while ‘streetwear’ is a commodity founded in fashion,” he once said. Virgil’s community was just as much a part of his vision for the house as his designs, and his shows and collaborations provided an opportunity to bring more people to the table. Another great line of his: “When you’re lucky enough to get a ride to the penthouse, it’s your duty to send the elevator back down.”

Much can, and will, be said about Virgil’s impact on the course of fashion history. Yesterday, however, it was simply clear to see. In just eight collections, Virgil radically shifted what Louis Vuitton’s menswear could look like, and therefore what it could mean to a whole new generation of guys from around the world. Who knows what will happen next, but for now, it served as a culmination — and celebration — of his short-lived but long-lasting lasting legacy. Long live Virgil Abloh.