Despised, disputed, adored: paparazzi are undoubtedly amongst the most colourful figures in the history of photography. Privy to births, breakups and betrayal, their presence truly knows no bounds. PAPARAZZI! – an ambitious new exhibition in Vienna – examines the influence and aesthetics of the so-called ‘stolen image’, compiling around 120 works by approximately 20 photographers whose subjects range from Brigitte Bardot to Lenny Kravitz.

The term paparazzo can be traced back to the fictional photographer of the same name in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960). The film follows Marcello Rubini, an embittered tabloid journalist navigating the high society of Rome in pursuit of his next story. At his side is Paparazzo, a dogged photographer who will do whatever it takes to get the money shot.

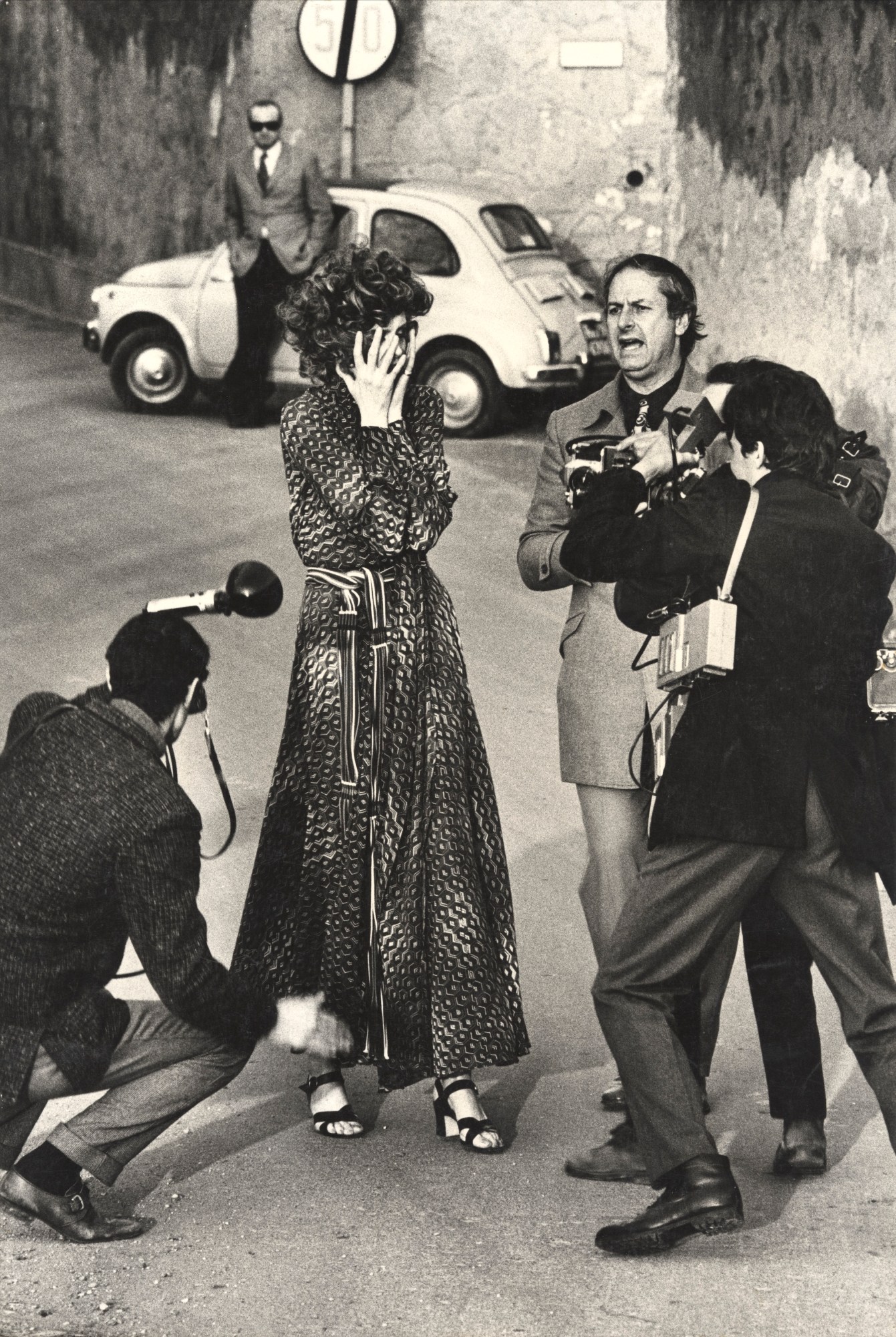

“The Italian movie industry and Cinecittà really had a boom at this time with a lot of international and Hollywood productions being produced in Rome,” exhibition curator Fabian Knierim says. “Italy, like many other countries in Europe, was slowly recovering from the war, and a group of predominantly young men seized the opportunity the influx of movie stars presented to them. Their methods were rapid and inventive, and they worked hard to land on the front pages of the world’s papers.”

There are several origin stories of how Fellini came to call his character Paparazzo. In an autobiography, he wrote that the name comes from an opera libretto. Another story goes that the word is a contraction of “pappataci”, meaning mosquito and “ragazzi”, meaning guys or boys. Fellini also once said the name sounded, fittingly, “like a buzzing insect, hovering, darting, stinging”.

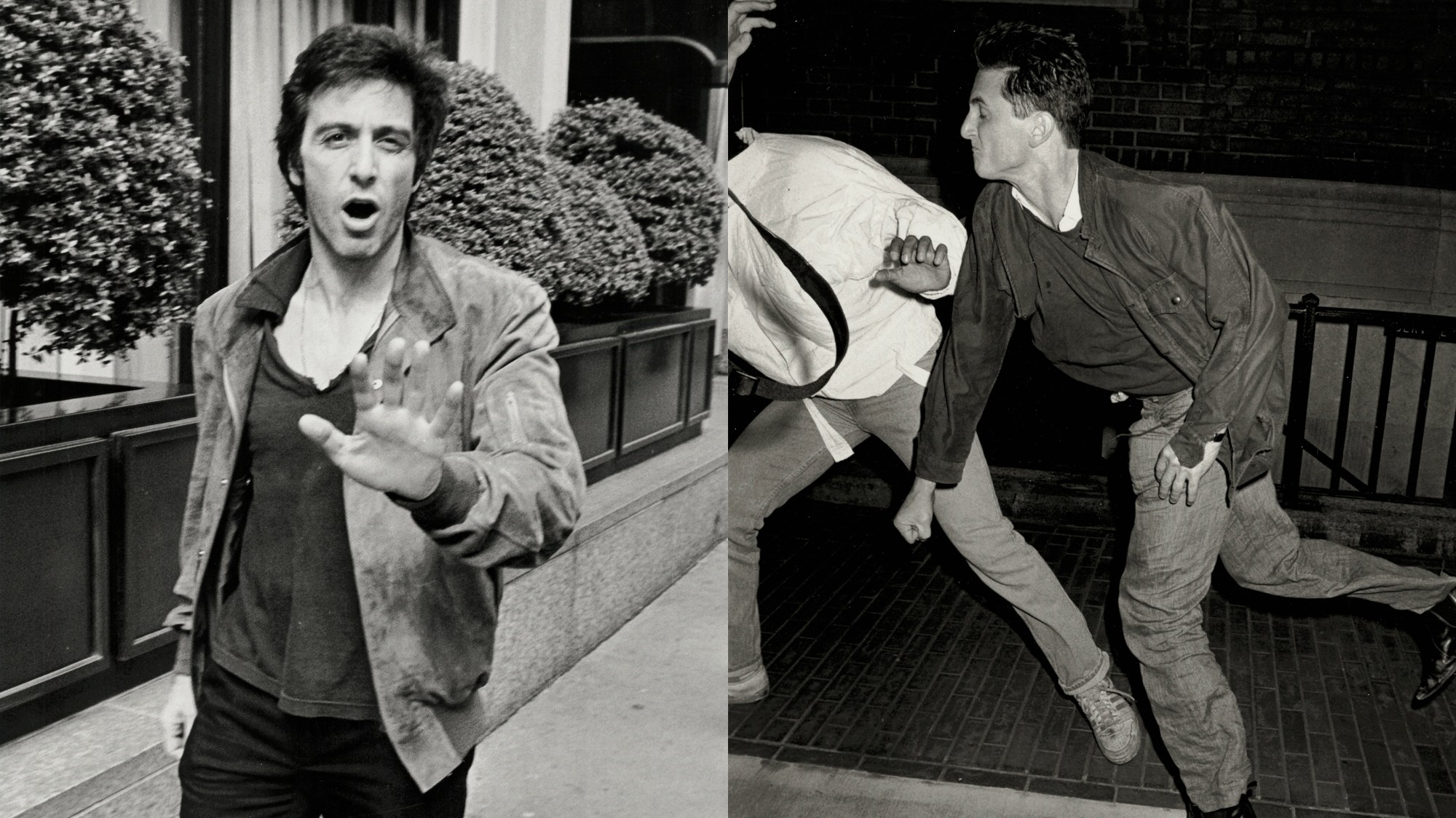

From the late 50s to the mid-60s, paparazzi photography earned its reputation as a predatory practice whereby the ambitious tousled to catch unposed, informal images of stars like Michelangelo Antonioni and Sophia Loren. In production for La Dolce Vita, Fellini was famously advised by one of the original celebrity-hounding street photographers of the day, Tazio Secchiaroli. In a particularly tenacious pursuit of Ava Gardner and Walter Chiari, Tazio set off a flash close to Ava’s face and was rushed by an angry Walter while his partner Elio Sorci watched the drama unfold through his viewfinder.

The exhibition catalogues similar memorable moments, including a case of life imitating art as Anita Ekberg defends herself against the intrusive paparazzi with a bow and arrow. Fabian describes the circumstances of the exhibition’s most iconic image: “A group of three or four men had been hounding [Anita] all evening and eventually followed her to her house and were waiting outside her door. She reemerged from the building fully fitted with a prop bow and arrow and shoots it straight at them. In one pap shot taken by Marcello Geppetti, the actress appears as a small figure in the dark distance pointing the arrow directly at the camera. She is quite literally shooting back at them. I think it’s such a powerful image of reclamation.”

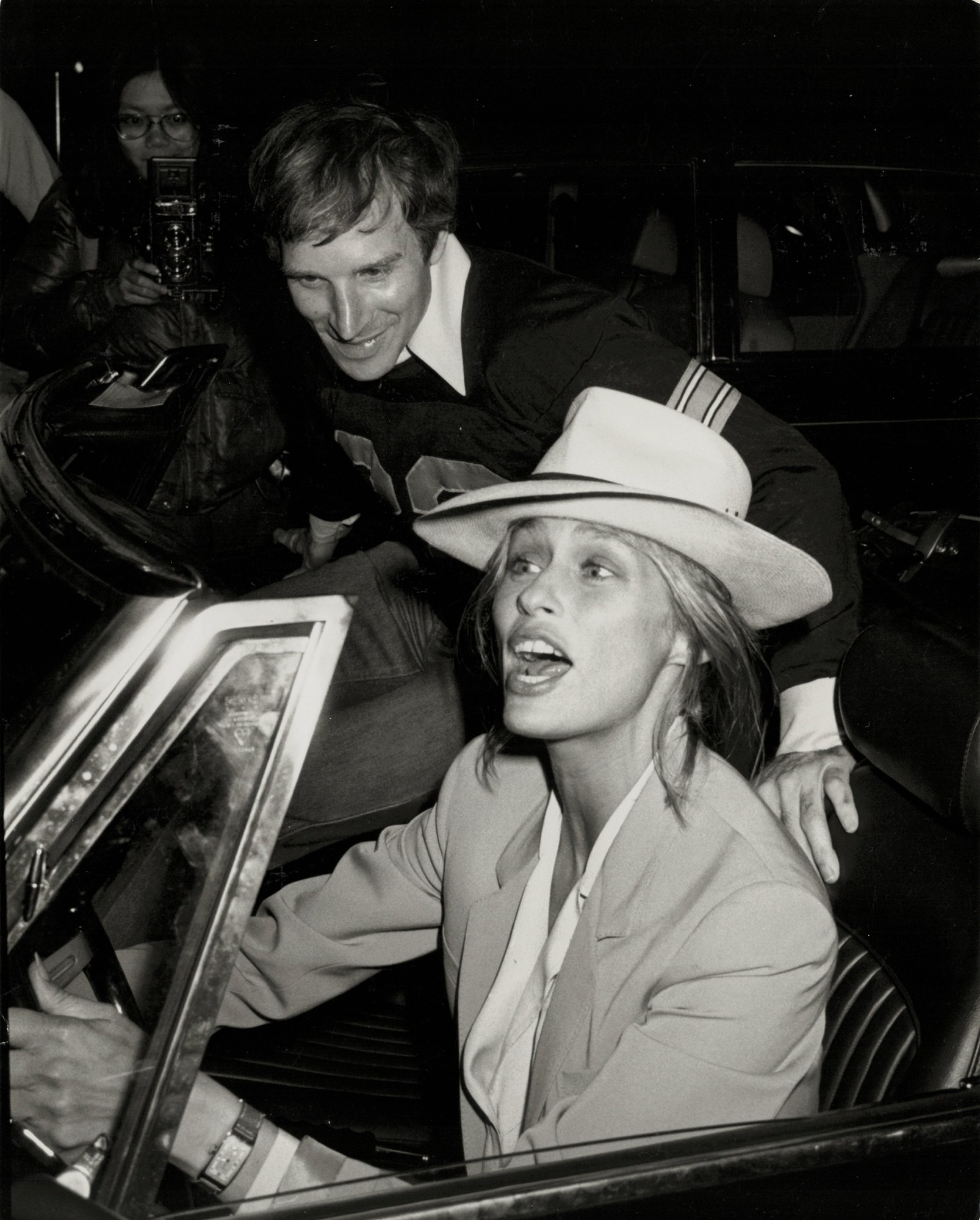

The relationship between celebrities and paparazzi is complex to say the least. While some personalities navigate this attention with precocity, leveraging it for publicity, others struggle under the constant scrutiny. The photographers that followed Britney Spears’ every move throughout the scandalmongering 00s, for example, vilified and shamed her to the point of exasperation, fuelling public displays of frustration.

“I think you can very much see the division of gender roles in [Britney’s] case,” Fabian says. “You have a female subject and mostly male paparazzi who perform as vehicles for the male gaze, monitoring how women should behave and how their bodies should look.” When Britney shaved her head in 2007, pap shots were being sold for as much as a million dollars.

The ruthless means with which paparazzi photographs are obtained surfaces the age-old debate around the ethical boundaries of journalism and the right to privacy. But while many would consider the role of the paparazzi as a morally dubious one, there’s a case to be made for them fulfilling a wider web of desire for celebrity images. “The paparazzi serves as the eye for all of us,” Fabian says. “We try to distance ourselves from the controversy of their position, but in the end, we all like to gossip and feed our voyeurism, and they nourish that. In La Dolce Vita, there is depth to the character of Paparazzo. He is a key figure of popular culture, akin to the private eye in a pop novel. They are a product of the star system but on a broader scale, a product of the spectacle of society we are living in.”

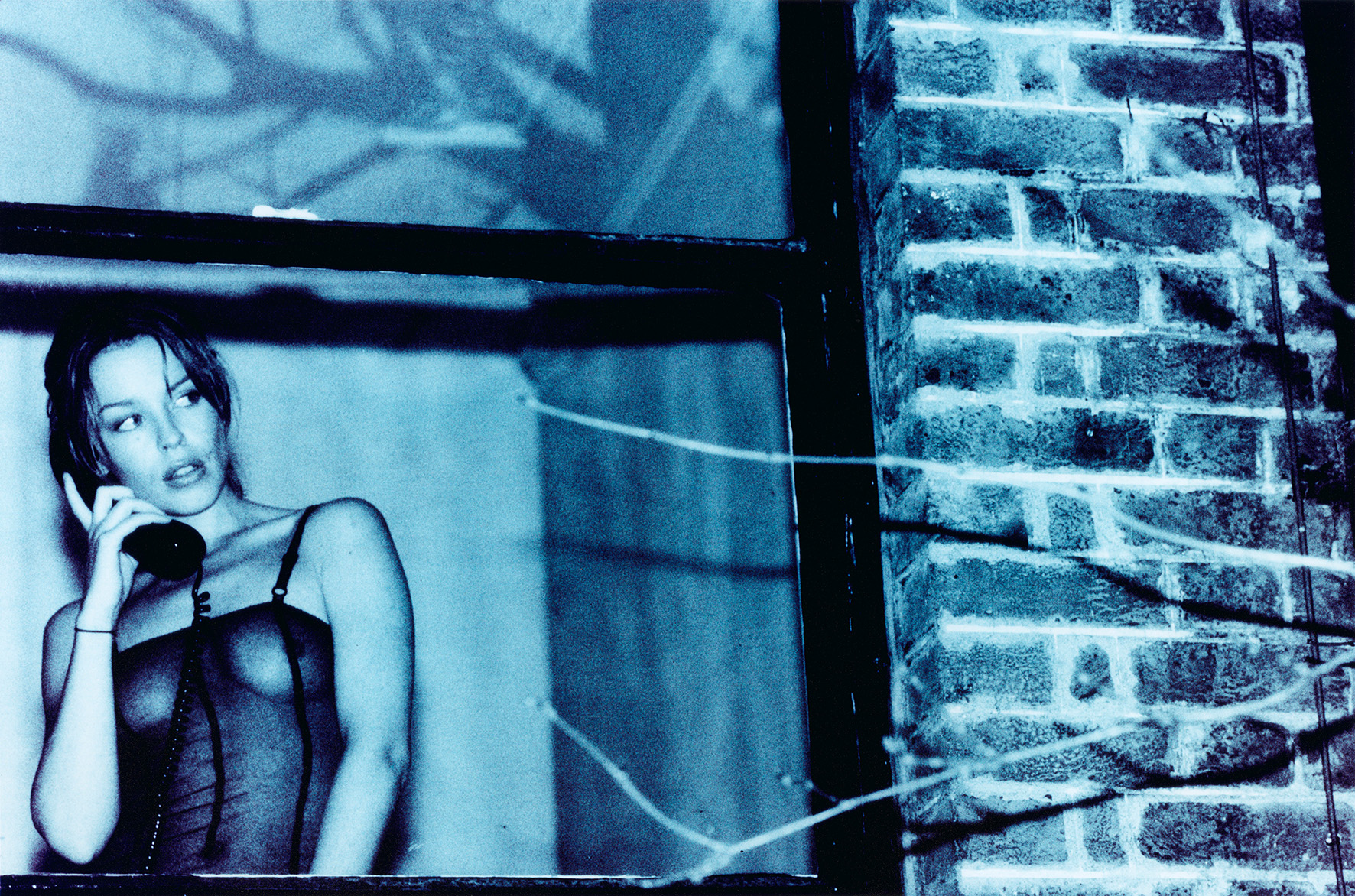

While social media platforms amplify the reach of paparazzi-style content, they also muddy the waters between traditional paparazzi and everyday individuals seeking a glimpse into the lives of the rich and famous. Instagram has succeeded in demystifying our construction of ‘celebrity’ somewhat, but an incessant appetite for the non-curated suggests that there will always be a place for a grainy telephoto lens pap shot of some hot young couple on a yacht.

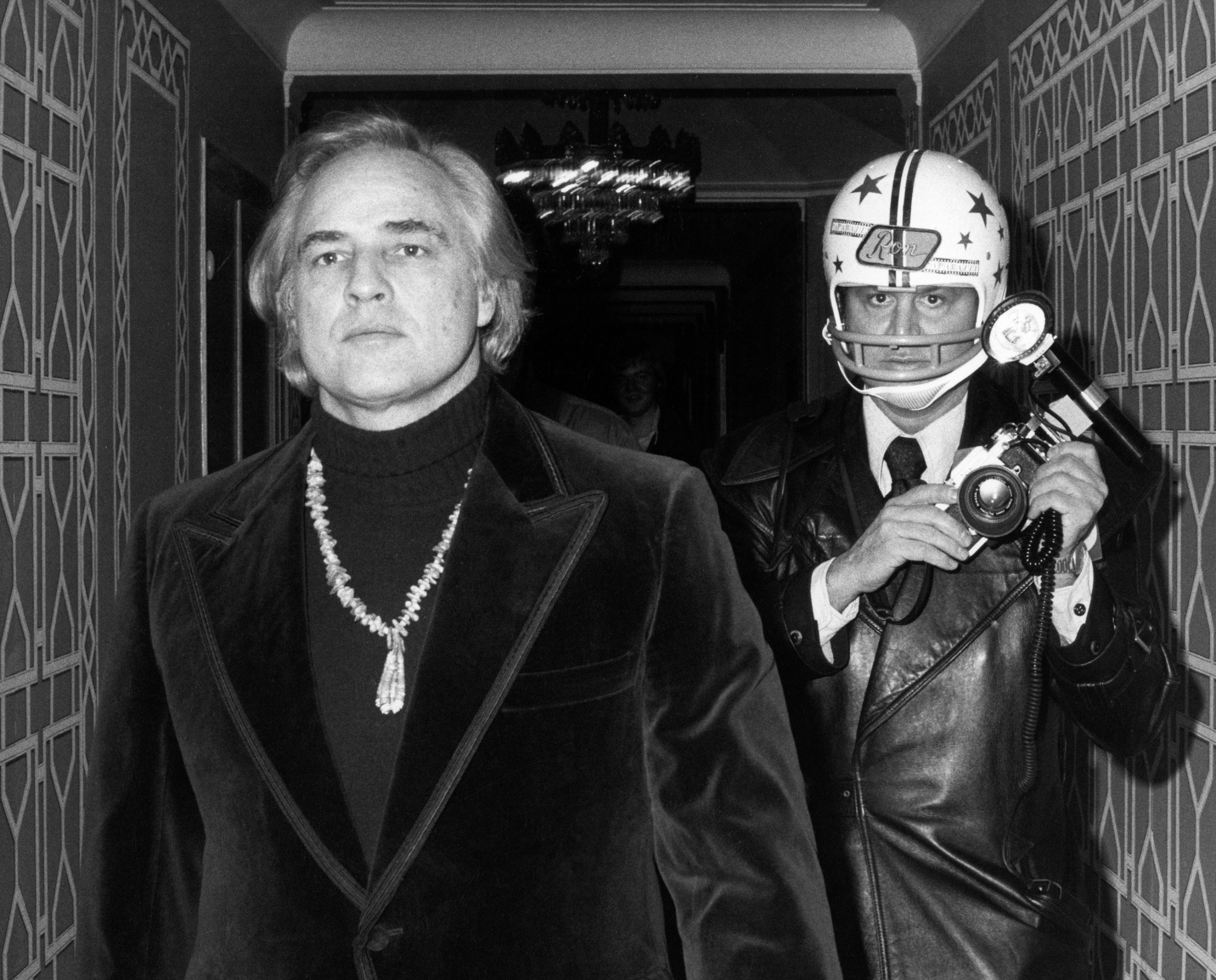

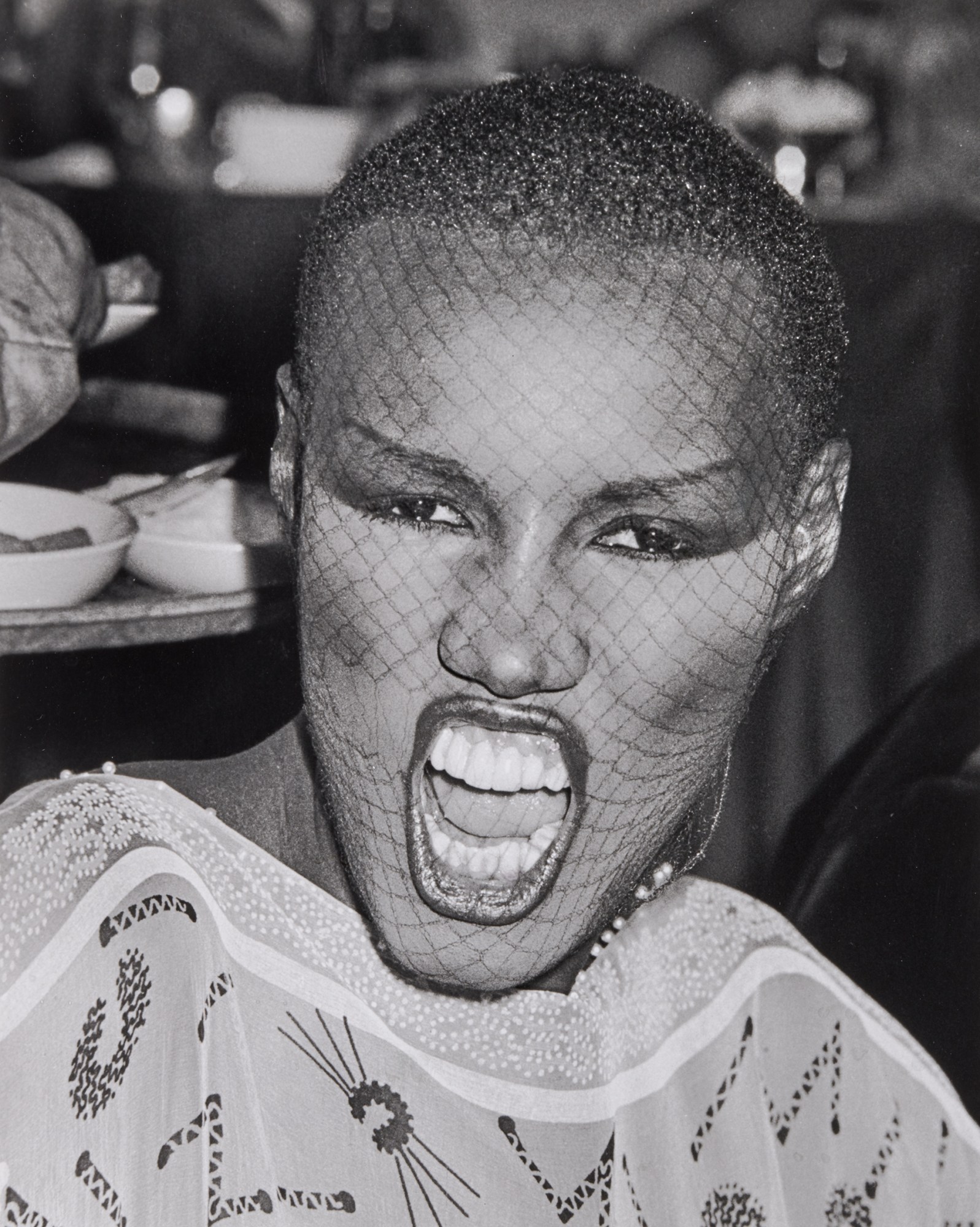

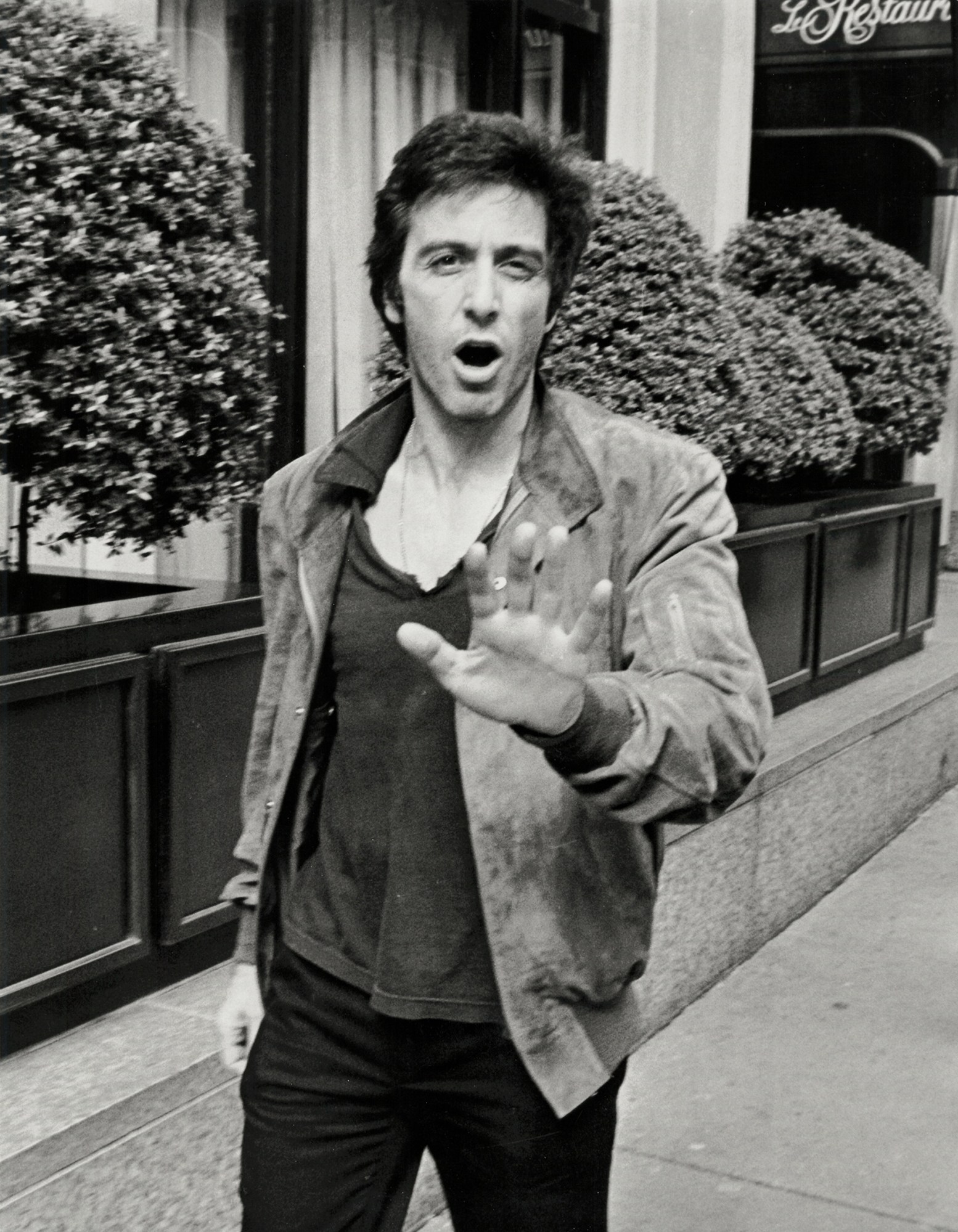

It’s only recently that the view on the history of paparazzi photography has changed. Today, the images of outstanding representatives such as Ron Galella and Marcello Geppetti are appreciated as unbiased portraits and testimonies to an era. The exhibition has admirable scope, acknowledging the fascination that the phenomenon has repeatedly exerted on other areas of image culture and art via series by Helmut Newton, Anton Corbijn, Alison Jackson, and the Austrian collective G.R.A.M. From the late 90s until the early 00s, G.R.A.M. appropriated the paparazzi style of photography, manipulating images to re-contextualise everyday scenes into dramatic moments loaded with secrets. Photographs of celebrities and regular people hang side by side, calling into question the authority of celebrity fetishism and deceptive media on perception.

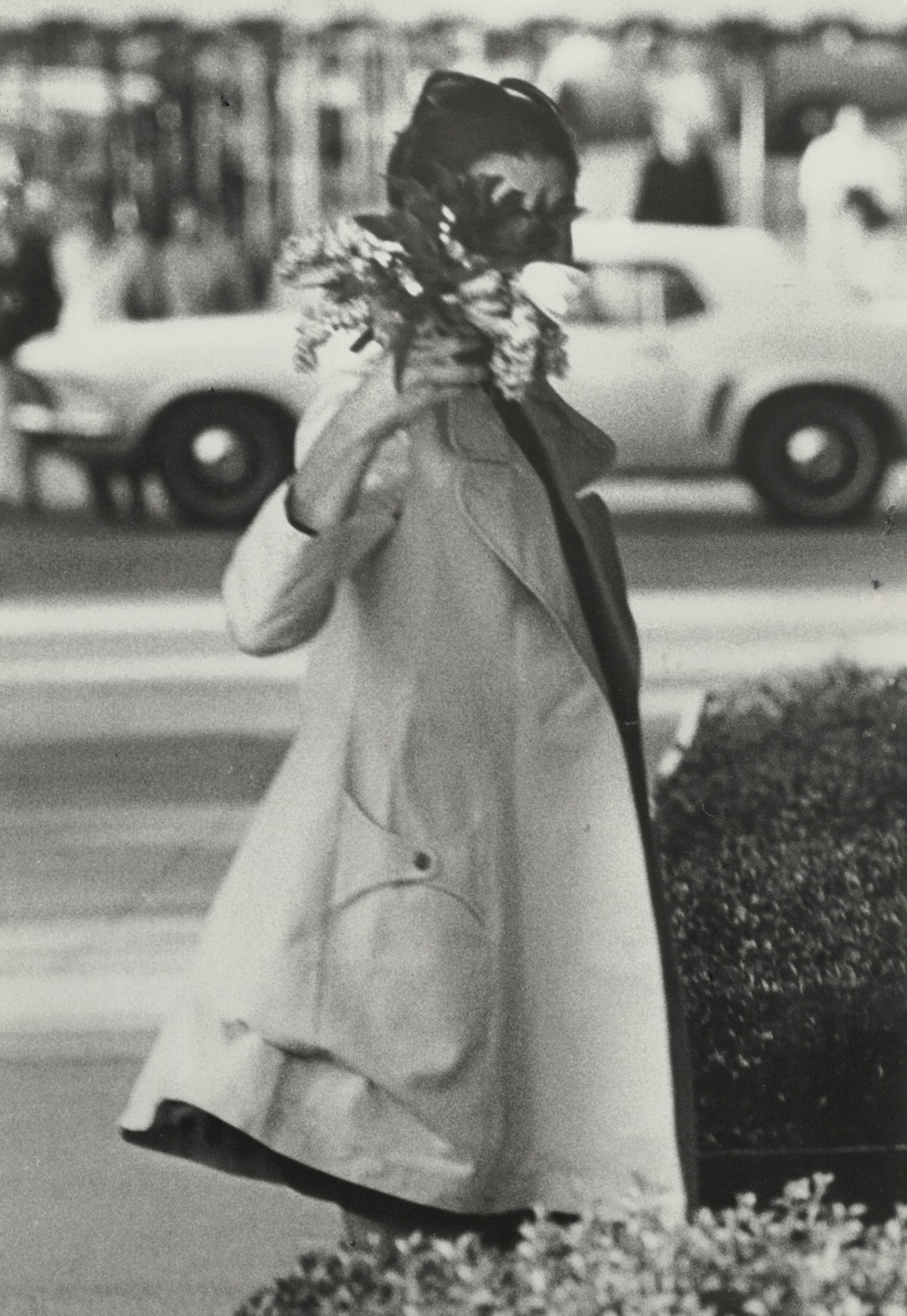

“What I hope PAPARAZZI! highlights is this real appreciation for a photographic craft grounded in authenticity and directness,” Fabian says. “These are images that are often out of focus with layers that obstruct the view. They’re always an image that is cut out from a larger narrative. In this sense, they are also cinematic. The viewer is considering the before and after of the shot. What led us to this moment?”

In an age where the line between public and private spheres blurs with each click of a camera, examining this fascinating genre becomes more than just a glance into celebrity culture — it’s a microcosmic practice of our society’s evolving relationship with images, fame, and the intricate dance between public attention and personal privacy.

‘PAPARAZZI!’ is on view at Westlicht Museum for Photography, Vienna until 11 February 2024.

Credits

Images courtesy Nicola Erni Collection, Marcello Geppetti Media Company, Helmut Newton Foundation, Alison Jackson, Anton Corbijn / Antonymous B.V. and Ron Galella Ltd.