As a biracial teenager growing up in the early 00s, Andres Norwood knew he had to watch his back in Highland Park — a predominantly Latino neighbourhood in Northeast Los Angeles — where his mum taught at school and he used to party. The Highland Park Gang were targeting Black people indiscriminately: they murdered a man in his sleep, shot a 15-year-old boy on his bike, beat people up and scrawled racial slurs on a family’s driveway. In a 2006 gang trial, they were painted as a hate group and prosecuted under laws typically reserved for white supremacists.

For Andres, whose mum is Chicano, a third-generation Mexican from Chihuahua, and dad is an African American from Detroit, his “Blaxican heritage”, as he calls it, wasn’t understood. “You’re kind of conflicted between two cultures,” Andres says, and because of the gang culture, he was forced to pick a side. “I gravitated towards my Black side because I felt like I was more accepted because of the way I looked, and the way people perceived me.”

At his Catholic school in Montebello, and among the Mexican community of Alhambra where he lived, Andres faced discrimination: “[People] knew I was Mexican but they didn’t accept me in that light, so I was constantly having to prove myself.” In part, he blamed the sprawling nature of LA where “everyone’s kind of segregated,” and stays within their communities: “it’s very conservative and not so open-minded.”

It wasn’t until Andres moved to New York at 27 that he felt truly accepted. “It was so fulfilling because there’s so many Afro-Latino cultures out here: you have the Puerto Ricans, Haitians, Dominicans and even Colombians, so people are exposed to that and everyone’s mixed,” he says. “It made me proud of who I am.” A trip to the Mexican states of Guerrero and Oaxaca — where large populations of Afro-Mexicans reside, many descendents of slaves trafficked in the colonial era (about 15 times as many were taken to Spanish and Portuguese colonies than to the US) — inspired the photographer to turn his lens on the Black Latinos at home.

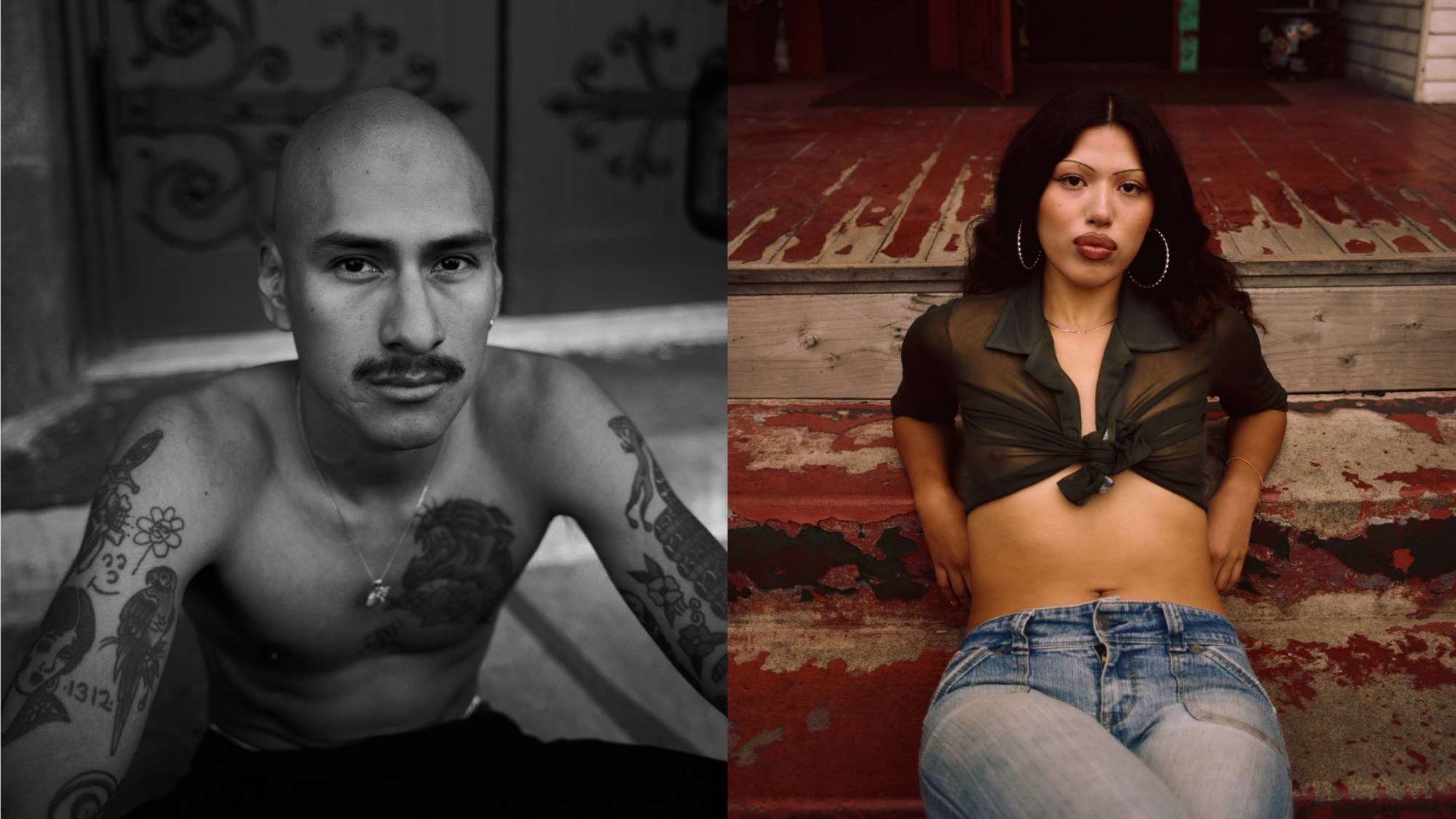

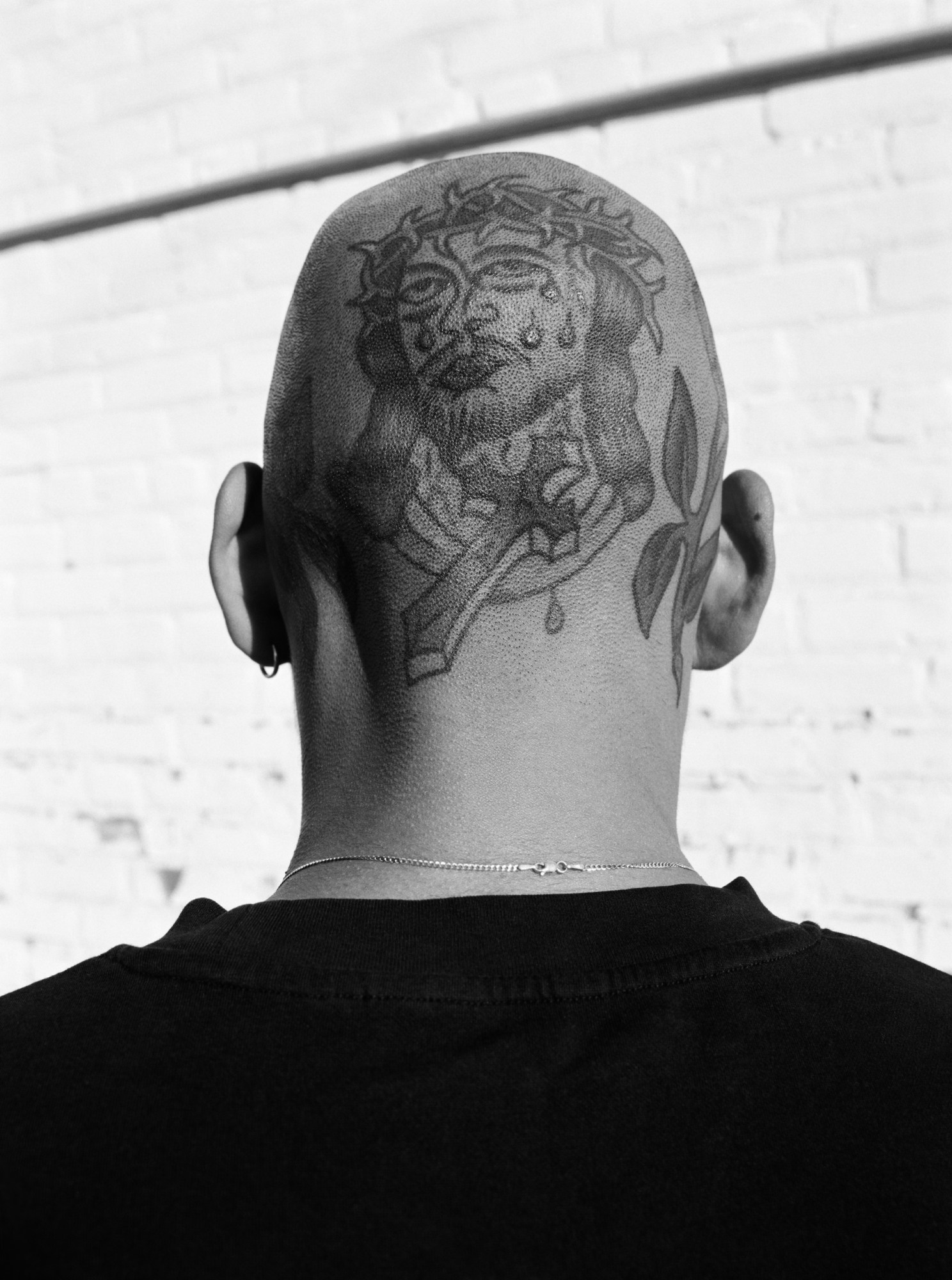

In a series of portraits that were taken earlier this year for LA Conexion, a collaborative show with the Jamaican-Puerto Rican artist Wendell Cole, he showed his Latino and Afro-Latino friends from the East to the West Coasts. There are powerful black and white photographs of Chachi on the stoop of a brownstone in Brooklyn, including one of the back of his head inked with the Catholic iconography of a Jesus weeping. In Montebello, Zion bears a tattoo on his chest of the African continent combined with a Mexican flag; while Fresa in Panorama Heights drips in gold necklaces and flaunts bold cat-like makeup. Kim in Boyle Heights has razor-sharp eyebrows and huge hoop earrings, cutting a striking figure that would not be out of place in a fashion magazine.

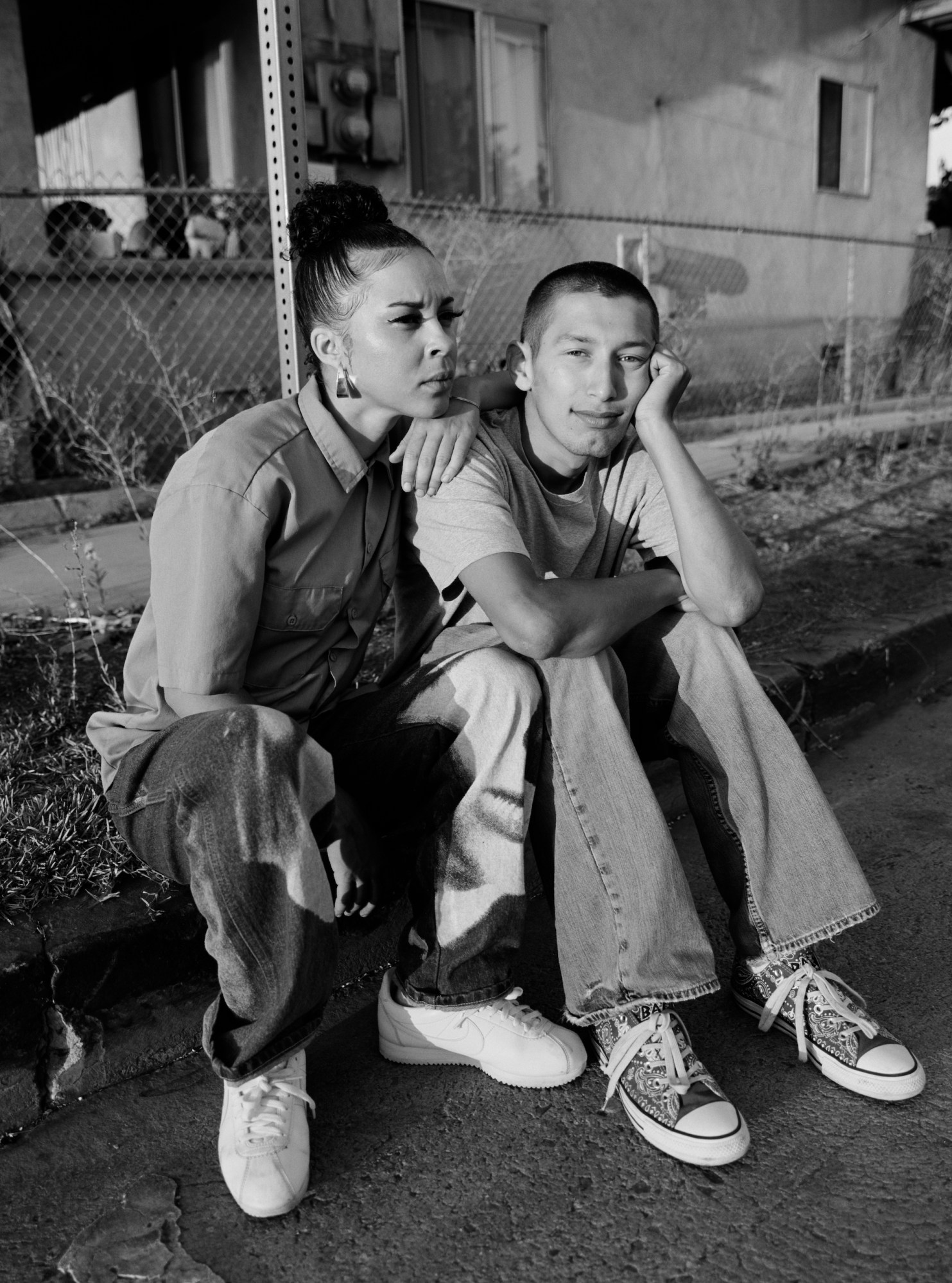

Carmelita Mae, who Andres has been friends with since high school, sits with her brother on their block in Boyle Heights, where her Mexican family has lived since 1905 in a house they proudly own. “If you know me, you know where I live,” she says. Her father, who was Black, faced “total racism” from her mum’s Mexican side, which involved her grandfather chasing after him with a shotgun to stop the pair from marrying. They did anyway, ultimately having four children together, before Carmelita’s dad passed when she was young. It meant she was raised by her mother’s side in the predominantly Mexican neighbourhood and gravitated towards that part of her identity.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

Carmelita has light skin too, so didn’t face the same colourism that her darker-skinned siblings did in a society that believed social mobility was tied to complexion. According to Pew Research Center’s National Survey of Latinos, half of Hispanic adults said discrimination based on race or skin color is still a “very big problem” in 2021. But that’s not to say she didn’t get racist remarks: “we get questioned for being in our own neighbourhood,” she says.

Even to this day, some of Carmelita’s Black friends refuse to visit her in Boyle Heights — the last holdout to gentrification in LA, where residents fight against rising house prices and white art galleries, and cling onto the borough’s Chicano identity. “I’ve had ex-boyfriends drop me off and be like ‘run to the house because I’m not sitting in a car out here.’” She didn’t experience the same fear of gang violence as Andres and her brothers — who have been held up at gunpoint on more than one occasion — but understands that crime is all too often racial.

Microaggressions are also common, with her Latino friends and family commenting that she doesn’t look Black or speak Black. “It just really gives me that insight into the expectation people have of what a Black person is and what that kind of person should sound like,” she says, adding that there’s often a fetishization of her racial ambiguity.

After George Floyd was killed, Carmelita remembers that a lot of her Mexican friends were coming forward “fighting for victimhood,” saying things like: “what about brown lives?” But that’s not the point, she says, “We are both equal in this struggle, because sadly this is more of a white America.”

The Puerto Rican scholar, Miriam Jiménez Román, who chronicled the Afro-Latino experience in the US, told The New Yorker in March 2021:. “Until we understand and recognize that we have our own biases, our own prejudices, our own hierarchy, and our own issues with white supremacy, we really can’t address those other issues that affect all of us.” She continued, “All lives matter, yes. But if you don’t talk about the lives that seem to receive the least attention, the lives that have no value, those who have been told they’re basically worthless — until we give value to the worthless, nobody has any worth.”

What Andres hopes his project will show, in capturing the diversity of the Latino community on both the East and West Coast, is that there is space for both to exist.

Credits

Photography Andres Norwood