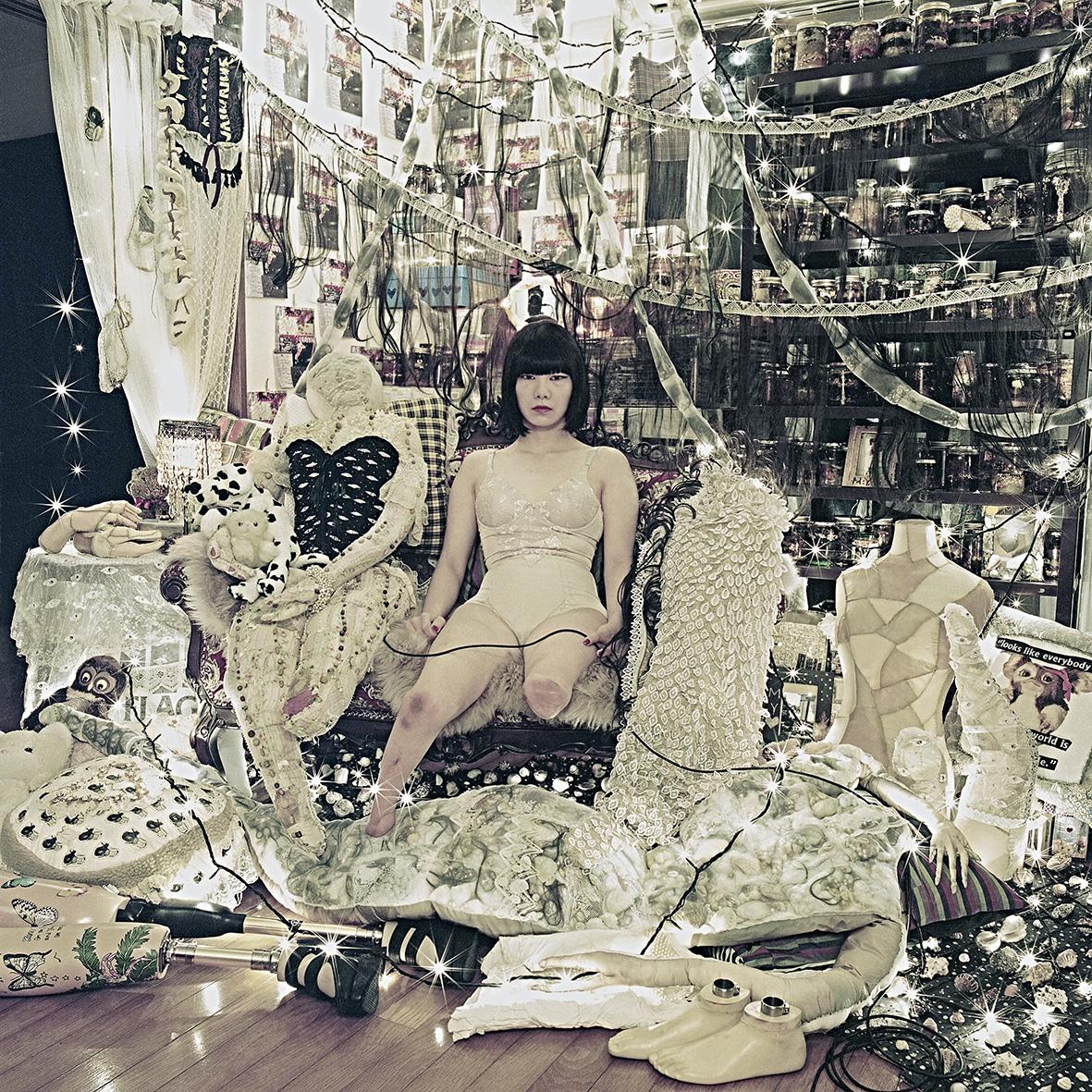

With her customary look of cool defiance and a sharp black bob, Japanese artist Mari Katayama stares ahead in the centre of her childhood bedroom. The walls behind her are barely visible beneath patches of fabric, hanging beads, illustrations and stacks of boxes, while the trove of objects at her feet include prosthetic limbs embellished with painted garlands, and stuffed fabric mannequins that have been sewn by the artist.

It is in this bedroom that Katayama’s life-long compulsion to stitch, cut, model and make was first stirred. Its cornucopia of hand-made objects is testament to the symbiotic relationship between craft and photography that has shaped her work ever since. The photograph in question is part of leave taking (2021), a new series of work that will be displayed as part of her eponymously titled exhibition at Kaunas Gallery, Lithuania, her largest outside Japan.

Born with tibial hemimelia, a rare congenital defect that left her with a cleft hand and both legs severely shortened, Katayama first immersed herself in craft as a matter of necessity. The crude prosthetics she wore as a child made finding clothes impossible; coming from a family with a strong DIY ethos, learning to make her own garments was the obvious solution. “Ever since I was a child, my entire family was always busy making things around the house,” says Katayama. “Sewing clothes, ink painting, writing haikus… I owned a needle, thread and a brush before I could even write.” Making became, “the natural thing to do” for Katayama and so, when she chose to have both legs amputated at nine, her ability to retreat into a world of uninhibited creativity helped her make the transition on her own terms.

It was in 2011, while studying art history at university in Tokyo, that Katayama’s artistic awakening began in earnest – though not in the way you might expect. Working as a late night jazz singer helped with her course’s tuition fees, but it also gave Katayama the chance to reinvent herself. “Every day I wore a wig, heavy make-up and a long dress to go on stage and sing,” she says. “I hid the fact I had two prosthetic legs and only two fingers on my left hand. No one ever found out about my disability until the end. I’d been deceiving people with my appearance all my life, so it wasn’t new for me.”

During one performance she gave wearing flats, Katayama recalls being heckled by a drunk member of the audience who told her that, without heels, she could not be considered a woman. “It was as if I had found myself in a situation where I had given up and run away instead of facing up to what I couldn’t do,” she says. The experience prompted her to visit a prosthetic limb factory and develop new prosthetics that could be worn with high heels. The resulting High Heel Project has been ongoing ever since, and sees Katayama take to the stage in vibrantly coloured five-inch stilettos to perform as a singer, model or keynote speaker. Earlier this year, Katayama partnered with Italian luxury shoemaker Sergio Rossi on a special series of heels, and in 2024, she hopes to participate in the Venice Biennale for a second time with work she has undertaken as part of the project.

The prosthetics themselves have become a recurring motif in her photography, often appearing as embellished props within an ornate mise-en-scène that Katayama meticulously plans with illustrations and diagrams. Whether in her studio, bedroom or outdoors, the languid nature of Katayama’s pose bears traces of Botticelli or Titian, elevating her body with an elegance and grace rarely afforded within historical portraiture while questioning the idealised female form it has endlessly reproduced.

Defying limitations, turning obstacles into opportunities and disrupting narratives around disability have all been a natural part of Katayama’s rise to international fame. Photography entered her repertoire by chance. Using a shutter release and herself as a mannequin, she took photographs to share her hand-made creations over MySpace and Japan’s social network, Mixi. These meticulously arranged, somewhat accidental self-portraits evolved into her most recognised work as well as her activism. In bystander (2016) and on the way home (2016), Katayama crafts haptic, multi-limbed wearable sculptures (reminiscent of Sarah Lucas or Korean artist Lee Bul) that play with notions of otherness and alienation while responding to singular beauty ideals with a cascade of irregularly shaped limbs.

There’s a punky non-conformism too, a sense of sticking the finger to a country whose Eugenic Protection Law forcibly sterilised people with disabilities or mental illnesses as recently as 1996. “The Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics seemed to have increased the positive attitude [towards disabled people] a little,” says Katayama of her home country. “But those are over and unfortunately we seem to be going back to the old days.” Within this glacial speed of change, Katayama’s work is an increasingly urgent beacon of visibility for disabled people in Japan and a reminder that, in the artist’s words, “Everyone has the right to choose how to be seen.”

After becoming a mother for the first time five years ago and reaching a new, internationally acclaimed stage of her career, Katayama finds herself in a state of transition once again, shedding the need of her younger days to ‘fit in’ and her material efforts to do so. This process became the focus of last year’s leave taking, shot among the vestiges of her childhood bedroom. “A large number of objects I had created over the years were about to be entered into the permanent collection of a European museum, and I wanted to take one last group photo of these works,” explains Katayama, whose transparent, spectral appearance haunts each photograph.

“As I mended and photographed this collection of the last 20 years, I began to feel that I had made these objects as a substitute for a ‘correct body’. But I am now sure that I don’t need a ‘correct body’ any more. It is the objects that will disappear from my life, and the perfect pose I tried to attain in those works – almost like a mannequin – is equally not needed anymore.”

Credits

All images courtesy the artist