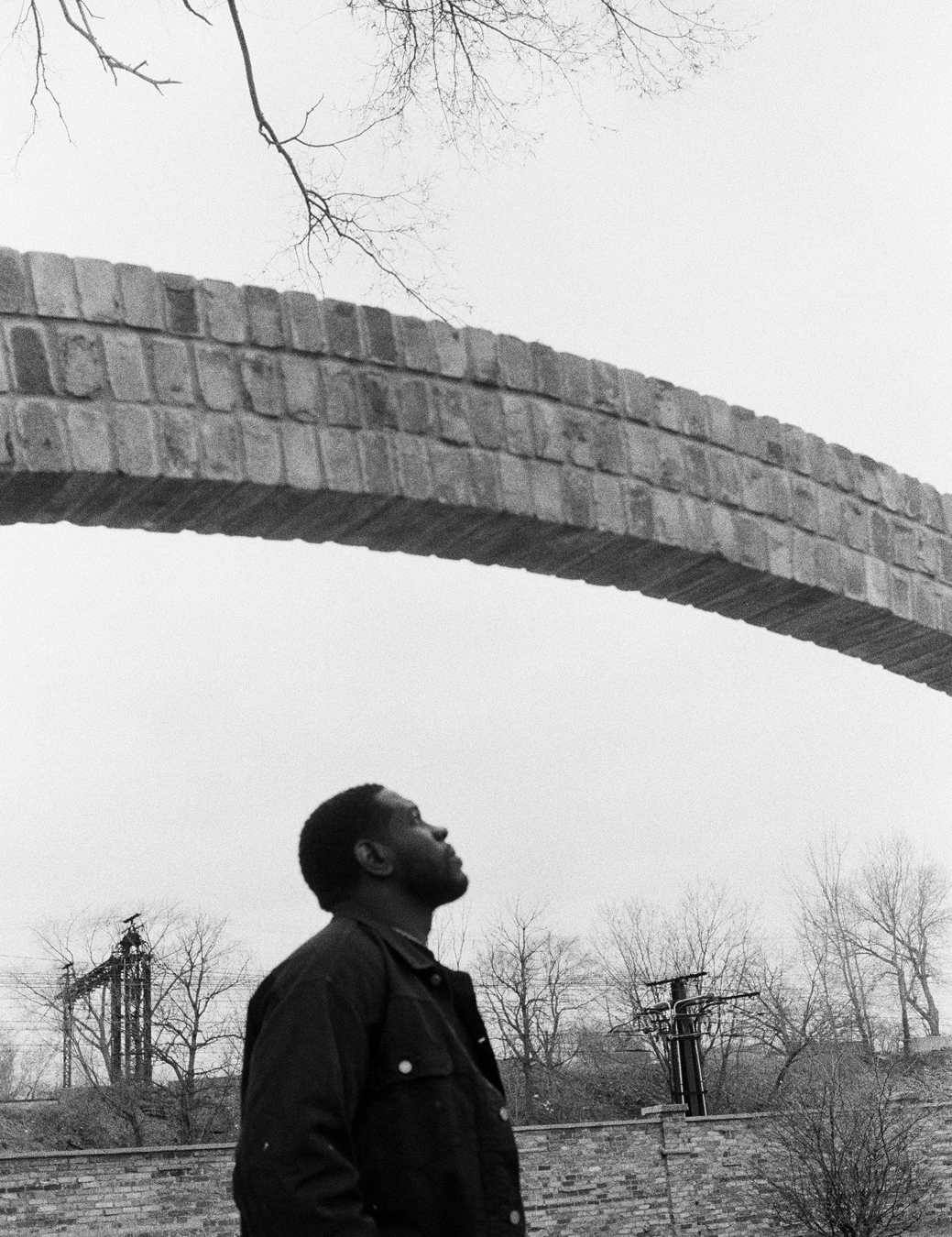

What do we know about Theaster Gates? Raised on the West Side of Chicago, he’s an artist known for his innovative blend of materials, civic-minded initiatives and modern spirituality. His work has reached many corners of the human experience, rallying for social justice and encouraging us to consider the world we live in in unique ways.

For example, in the work My Labour Is My Protest, shown in an exhibition of the same name at White Cube in 2012, Theaster sourced and parked a yellow fire-truck in front of the gallery and partially covered it with tar, a material associated with slavery. The fire-truck was from Birmingham, Alabama, and was decommissioned after the peaceful demonstrations of civil rights activists in spring 1963 were met with violence from the police, who used fire hoses and police dogs to disperse the protesters.

At the core of Theaster’s work is the idea that social change can come about through artwork; his labour is his protest. He is in no danger of submitting to apathy. His career as a professor at the University of Chicago while also leading the Black Monks – an experimental music ensemble – secures his status as a polymath, but it is his work directing the Rebuild Foundation that ensures this work is remembered through the lives of others. Rebuild is a not-for-profit established in 2010 to provide free arts programming while transforming vacant structures throughout the South Side of Chicago into cultural institutions, often turning the raw materials from these renovated buildings into community works. All of this has made Theaster a powerful voice for change in the art world, one which has traditionally overlooked BIPOC voices – ensuring that the community is at the heart of all things. Enter Easy.

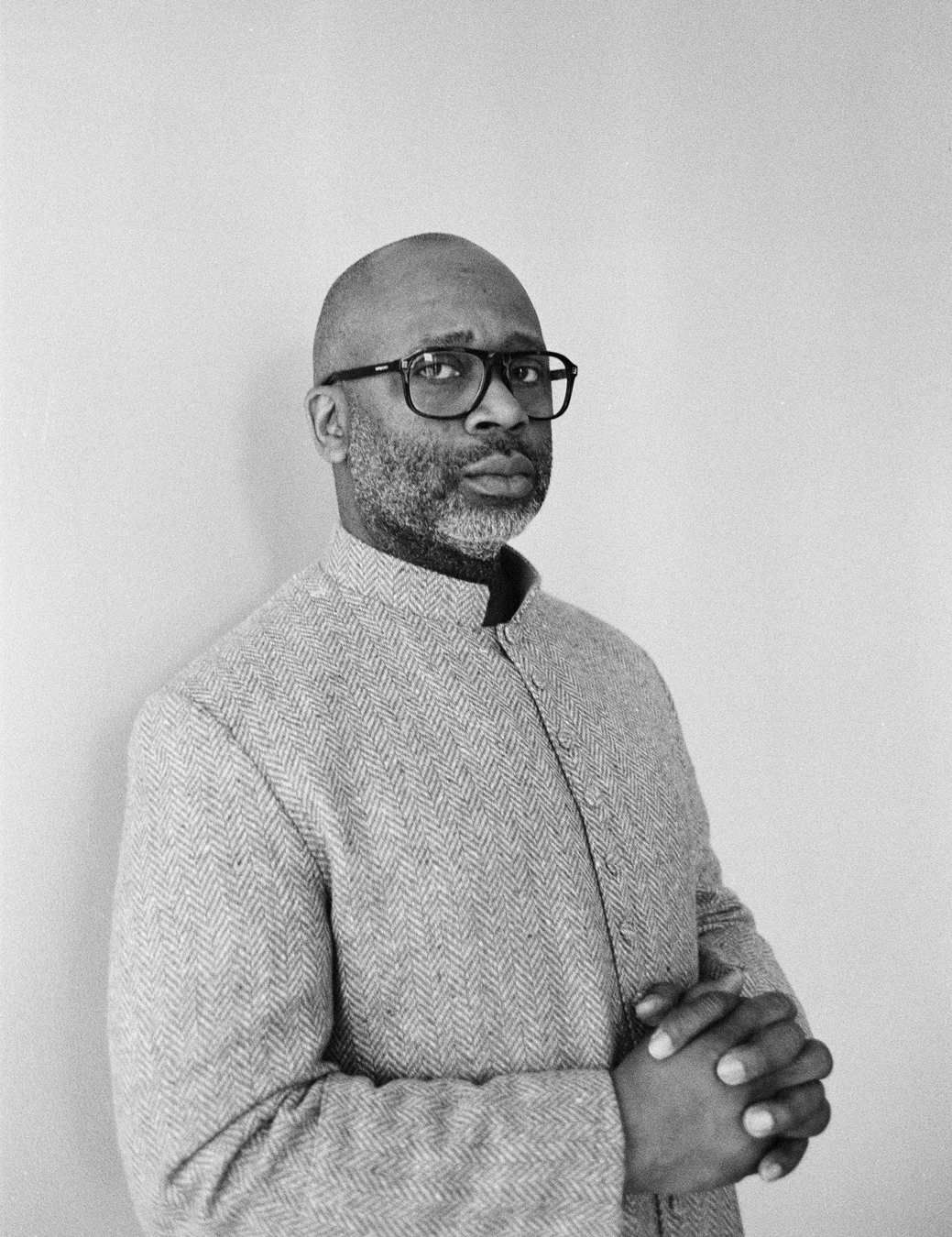

Easy is one of those figures you see everywhere one should want to be. Fellow Chicago native Isimeme “Easy” Otabor, founder of Anthony Gallery, streetwear buyer turned art gallerist, has partnered with Rebuild Foundation to produce a series of exhibitions highlighting the importance of Black space, Black art and Black artists at the Stony Island Arts Bank. Self taught, and an advocate for expanding the art world, Easy, with Theaster, has a vision to allow people to see art in ways that are more relevant to them. Theaster and Easy create art and bring art to people in ways that move people into self-interrogation, joy and learning, they create new ways of art having value where we live.

So we took some time to sit with these two inspiring figures, to hash out their frustrations, wrestle with what needs to be done, and celebrate the collaboration they have produced as a framework for other such initiatives.

Hey, everyone! I wanted to start by asking how the collaboration between you both came about?

Easy: I met Theaster a few years ago in passing, through Virgil. Man, I just loved what he was doing for the community. I think anyone who sees what Theaster’s doing in Chicago wants to be involved. And Theaster was receptive and open to listening to me, so I thank him every day for that.

Theaster: With Anthony Gallery being in the Arts Bank, it felt really mutual as Rebuild Foundation was trying to figure out how we could create more opportunities for Black entrepreneurs. Our buildings have amazing assets, and Easy and his squad offer this other level to a generation of young people.

“It’s hard to think you can do something when you’ve never seen it done before. Theaster has been showing me that things are possible.” Easy

When I was doing some research on Rebuild, I found an incredible quote: “Black autonomy alone is too radical for current America.” Theaster, I was interested whether you still think that Black autonomy is too radical and what this collaboration does to serve that purpose of breaking that apart?

Theaster: Even if I think it’s too radical, it’s something that I feel super committed to. You know what I mean? The hope is that by not just operating spaces, but owning spaces, Black people have the ability to control their destinies a little bit better. I think that this idea of Black autonomy is really just thinking about how we do business more deeply and support each other. It’s a radical idea, but it’s one worth pursuing. Easy is aligned with that. He would like to spend his dollars with people of colour. It’s been a really amazing match.

Some of the greatest movements and artworks in history are born from this sense of ‘doing it yourself’ and claiming space. I’m thinking about the BLK Art Group, an 80s collective whose self-organised exhibitions critiqued the institutional racism of the British art world, and the impact their work had on future generations. Autonomy and action are at the core of Black creativity. In the UK, we don’t have any real dedicated space to explore Black creativity like the Studio Museum in Harlem, or the African-American museums. Do you believe Black-owned spaces impact the history of Black art? How do Black spaces safeguard those practices so that we can see and understand them better?

Easy: To be honest, I just love being seen. When you see us working together it shows possibility. The biggest thing for the Black community is knowing that a dream and a vision can come true. It’s hard to think you can do something when you’ve never seen it done before. Theaster has been showing me that things are possible.

Theaster: I also think that when you look at the history of Black galleries and spaces like the Studio Museum in Harlem, the African American Museum in LA, that there had been, from the 50s and especially from the 60s and early 70s, a relationship between Black people’s political voice and desire to be seen, and the ability to manifest spaces where people can be unapologetic about the ways that they reflect on, celebrate and resist in Black and Brown spaces. So, I feel like the Arts Bank is part of a lineage. And I absolutely took cues from the Studio Museum in Harlem to try and create a space that was welcoming to all. But its mission was really about celebrating the things that Black people have made and have owned, and the culture in general, and that in some ways the Arts Bank and our other spaces should be indicators of how possible it is for others to do this work. We’re a miracle and we’re just representing what’s possible.

Theaster, how much of your work is about protecting legacies and archives, and also creating these, as you say, possibilities? I’m interested to understand whether you think that there are still limitations to presenting Blackness and Black experiences in white spaces or more institutional realms.

Theaster: The truth is I think that it’s good for artists to show in all spaces. We should not limit our agenda to a Black-only enterprise. If there are places that are dedicated to Richard Tuttle, Eva Hesse, Donald Judd, Arte Povera and Christo – and they’re committed to the preservation of modern art – then we should also have spaces that are dedicated to the possibility of a Black ideology and philosophy, to a Black aesthetic, to Black intention and Black makers. I would never ask the Chinese American Museum to reflect on the Black experience unless there was some adjacency between the Black experience and the Chinese experience, of which there are many, but you know what I mean? But I also love the fact that the Chinese American Museum in Chinatown may want to just talk about Chinese Americans in Chinatown. And by doing that, these culturally-specific institutions help to cultivate and preserve the truth of the legacies of people’s nations. That’s amazing. We don’t want to neglect or negate ourselves.

So perfectly put. I was really curious about the future of the programme. I’d love to hear about the selection process and how you’re engaging with the community.

Easy: It’s a step-by-step process. I wanted to roll it out in a way where we slowly get better and better every show, you know? Coming in on Theaster’s point about Black artists showing in different spaces. It’s interesting, our summer show – in a Black-owned building, with a Black curator in a Black gallery – will be showing Tom Sachs’ furniture. So doing the opposite of what we just talked about – I can’t wait for the kids to see it! These juxtapositions show the possibilities that are there, and encourage the younger generations to think about how art should be viewed. Our end of-year group shows are a bit more of a level playing field, showing the youngest to the oldest artists in the game. I want to include more women, women of colour, and Brown artists, you know? We really want it to be like, man, this is how it should be.

How has the reception been so far within the communities and with the different artists?

Easy: Just seeing people from the North Side that wouldn’t normally come to the South Side, and seeing them intertwine with people that they wouldn’t normally get to meet or talk to. That’s what I live to do: to make these spaces where these people wouldn’t normally meet, you know?

Theaster: Our chosen community comes through every Sunday to dance and kick it, but Anthony brought this new energy that felt a bit more turned up. And so, for the cats who were like, “Maybe they’re not really artists, maybe they’re just like skaters or into the music or fashion.” All these young cats, it was less siloed than in the contemporary art world I live in. It felt like people were coming out to support each other and kick it with their homies. There were a lot of friends of friends of friends. Now there’s a combination of the Bank’s historic audience with these other folk who are young and free. It’s such a good collision of cultures, and it reminded me again that Blackness is not monolithic. It’s nuanced and fly. There’s so many ways of being Black. Seeing a more complicated representation of that Blackness come as a result of these exhibitions that we’ve been having has been incredible.

You mentioned Blackness not being monolithic. I find this quote by Raymond Saunders interesting. In his essay, Black Is a Color, he states “Certainly the American Black artist is in a unique position to express certain aspects of the current American scene, both negative and positive, but if he restricts himself to these alone, he may risk becoming a mere cypher, a walking protest, a politically prescribed stereotype, negating his own mystery, and allowing himself to be shuffled off into an arid overall mystique. The indiscriminate association of race and art, on any level – social or imaginative – is destructive.” How do you negotiate political activism and art in your work and how does this collaboration reflect those values?

Theaster: I think that it’s reasonable that some artists would imagine that art is a political weapon or tool. And I think that some artists have that right. What I want to make sure of, though, is that if there are artists who feel like the only thing that they want their art to be is about creativity or catharsis or their own self-discovery, then I think that’s fine, that has every right to exist. I think the arguments around representation and abstraction have to do with how willing we are to make hyper-tangible our political or social beliefs and motifs. But for me, I want to make sure that a young person, when they are growing up, recognises that the arts could give them any number of ways of feeling vital and purposeful in the world. If they find themselves wanting to be activistic and they want to use their talents toward their activism, amazing. If they find themselves wanting to just paint the colour blue then they don’t have to say any more than that. You know?

“The hope is that by not just operating spaces, but owning spaces, Black people have the ability to control their destinies a little bit better.” Theaster Gates

Exactly.

Theaster: We have to make sure that we maintain a diversity and a balance of voices. It’s in vogue to be political, and maybe even the demonstration of your political activism leads to more capitalism. It becomes cultural capital and financially beneficial to say, “Oh, I’m about the environment,” “Oh, I’m about the police boycotts,” “Oh, I’m about that life of protests.” And sometimes you just got to check your heart and make sure you’re not on bullshit.

How do we safeguard the legacy of Black artists?

Easy: Buy what you like and support artists. Everyone should have the freedom to wake up every morning and do what they love and feel like they’re being supported.

Theaster: Easy, I’m thinking about the politics of collecting and cats that are now in it. Do you think art is important to everyday people who don’t have a whole lot of money?

Easy: The whole reason I started doing this was that I used to draw because I didn’t have a safe space. Being in high school, everyone, including my teacher was like, “Why you doodling? Why are you doing this? There’s no career in that.” People feel like the art world’s too intimidating, but there’s always a starting point. I come from streetwear, sneaker culture, fashion, and I think that’s what Anthony Gallery’s always striving to do, and that’s what Rebuild’s always striving to do: we’re asking ourselves how can we find access points to get people into places where we’ve been excluded.

How do we interrogate history within the museum space? How do we confront these pasts? How do we engage with new artists that are doing that work? There’s been a lot of resistance. I’m curious as to how you see this fitting in in Chicago and also in the communities that you’re building?

Theaster: It’s only been the last five years that any large white cultural institutions have been paying very close attention to Black art. We had to have national resistance and museum-shaming happen to consider the power of the Black voice and Black culture and to create opportunities for Black artists. Major institutions are in the middle of shifting their values and I think one of the main reasons, honestly, is because collectors started collecting more Black art. Black art became the hottest work being made in the world, right? It’s not as if some kind of affirmative action model has made museums change their minds. The truth is, people went where great art was taking place and it happened to be in Black spaces. Historically, institutions blocked Black artists because they wanted to protect the white artists that were coming on the scene between the late 40s and the 80s. So certain things never got written about, like Noah Purifoy or Martin Puryear or Elizabeth Catlett, Adrian Piper… take your pick. Artists had to make their own collectives. Things are wild at this moment because they’re resetting. I think it’s really important to look at these histories and to figures like Peggy Guggenheim as a model – once she liked something, whether it was Surrealism, Dadaism or Modernism, she bought it in-depth, she used all of her family’s wealth to buy as much art as she could. They bought art and then they had dinners for artists, and they had sex with artists, and they talked about artists, and they hired writers, and they took photographs. If there was any cue to that, it’s not enough to buy Black art, or to show it. We have to own the publishing companies and create new museums, in the

same way that Jewish people created museums when they were excluded from WASP museums. Unless we’re willing to do the whole thing, we will find ourselves fifteen years from now in the same fucking situation: mad because white people haven’t accepted us. This should be the moment where we do more than just expand our purchasing power. We have to expand our structural belief in the arts.

Credits

Photography Blvxmth