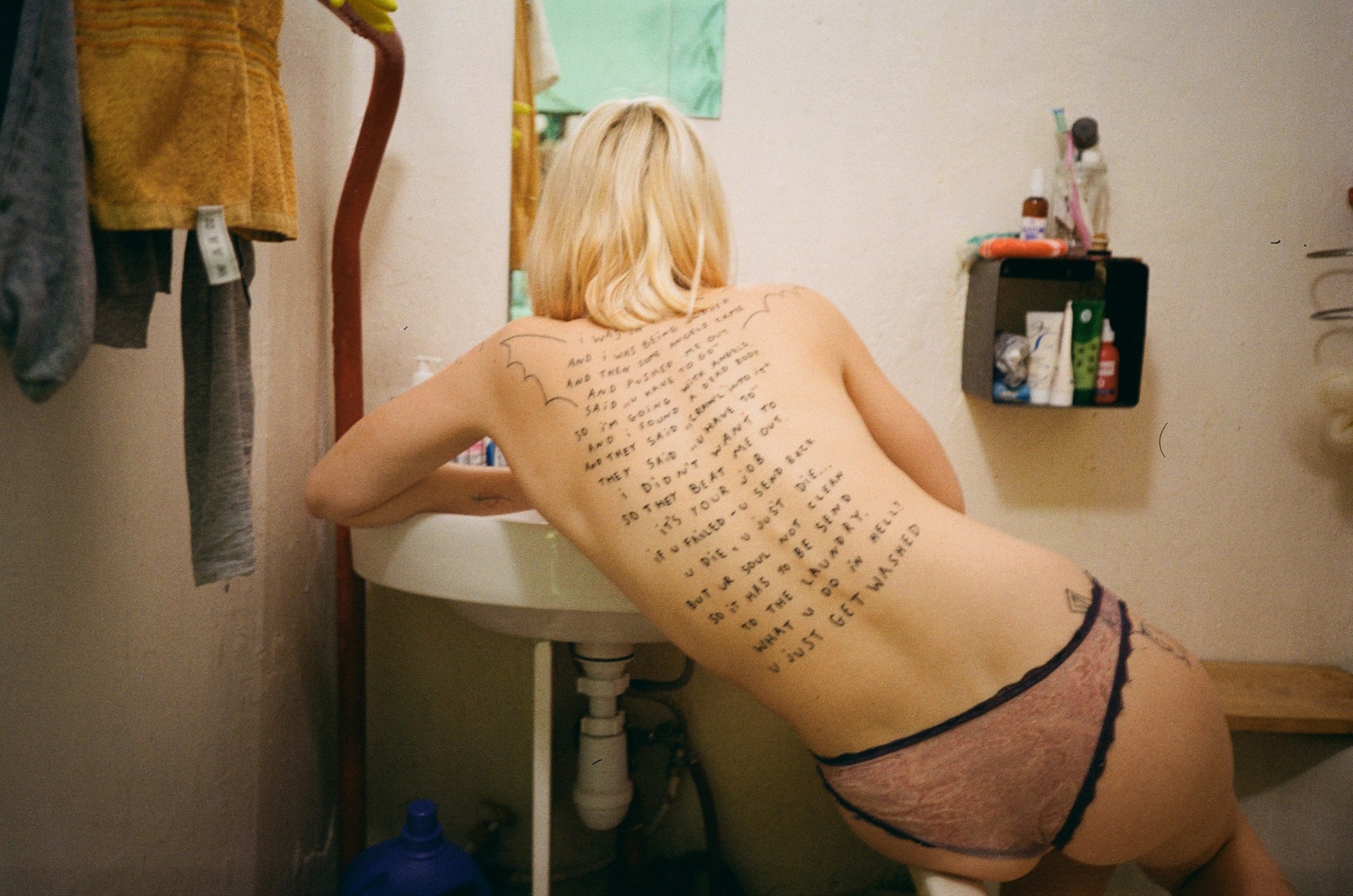

In her zine My Last Voyage in This Fucking World, photographer Sofiya Loriashvili has created an homage to her beloved native Ukraine. The slender publication is a time capsule of her last visit — in early 2021, across multiple cities within a two-month period — amongst Ukrainian friends and family. The settings are grungy rooms or the chilly outdoors; the subjects are playful or inscrutable. There’s a portrait of Sofiya’s tattoo artist in a Soviet-looking pharmacy; the interior of a drug dealer’s apartment with an unenclosed toilet, a lot of garbage and a cat; a suitcase-turned-dining-table riddled with paraphernalia (including Schopenhauer’s Metaphysics of Love); filthy bathtubs backed up with shaved hair.

The ensemble is hedonistic, spontaneous, undaunted — but underpinned by affection. Despite this wild spirit, the photographs have a built-in melancholy, highlighting the irreparable rift between then and now. The images of friends in a cemetery – with dark smoke from the crematorium engulfing the horizon behind them – are a queasy viewing in today’s devastating wartime context.

We met Sofiya at a coffee shop in Paris and discussed shrugging at nudity, the unreality of war and why the term “trashy” is sometimes code for “prude.”

You’re French-Ukrainian. What has your experience been around this hybrid identity?

I was born in Ukraine but came to France when I was five. My mom moved here: it was the idea of ‘Europe’ and it was ‘better.’ From ages 8-10, she got back together with my dad and we returned to Ukraine. Then we moved back to France when I was 10. I’ve lived here ever since, but I spend at least a month in Ukraine a year. My whole family is there, except for my mother.

Did you study photography?

I actually am just finishing my first year, at [Paris art school] Les Gobelins. I presented a portfolio of trash cans and portraits I made of people who were HIV positive. I’m going to school to have a framework in my life. I was getting out of rehab and needed structure. I’m not an autodidact — I don’t learn well on my own. I’m already doing photo, and I’ve done shoots for young designers, but if I want to push myself further and do commercial work, I need to take courses where I learn about lighting, etc. I need professors, I need constraints — having carte blanche can be complicated. I hadn’t been in school for a while, and it’s hard to get back to that rhythm, but it’s interesting.

How did My Last Voyage in This Fucking World begin?

The idea was to make a photo album. I used almost all the photos I took over about two months in Ukraine in February 2021 — good thing my computer organizes images automatically in iPhoto! — and I wrote about what I remembered. I am very, very attached to Ukraine. I have a little Ukrainian flag tattooed here [points to shoulder] — I speak about the country like it’s my mother. It’s always been a place of security for me. When I wasn’t doing well, I’d go. The air is different there. I mean not really, but. I don’t realize that a war is going on there — not really. What I do realize, concretely, is I can’t return. That’s what hurts: the fact that my home has been taken away, the place where I feel good. It’s like someone took away my mother’s breast. Maybe because I live in France, I have a strong link that even Ukrainians themselves don’t understand. But, in any case, it’s extremely present.

Can you tell me about the people in these photos?

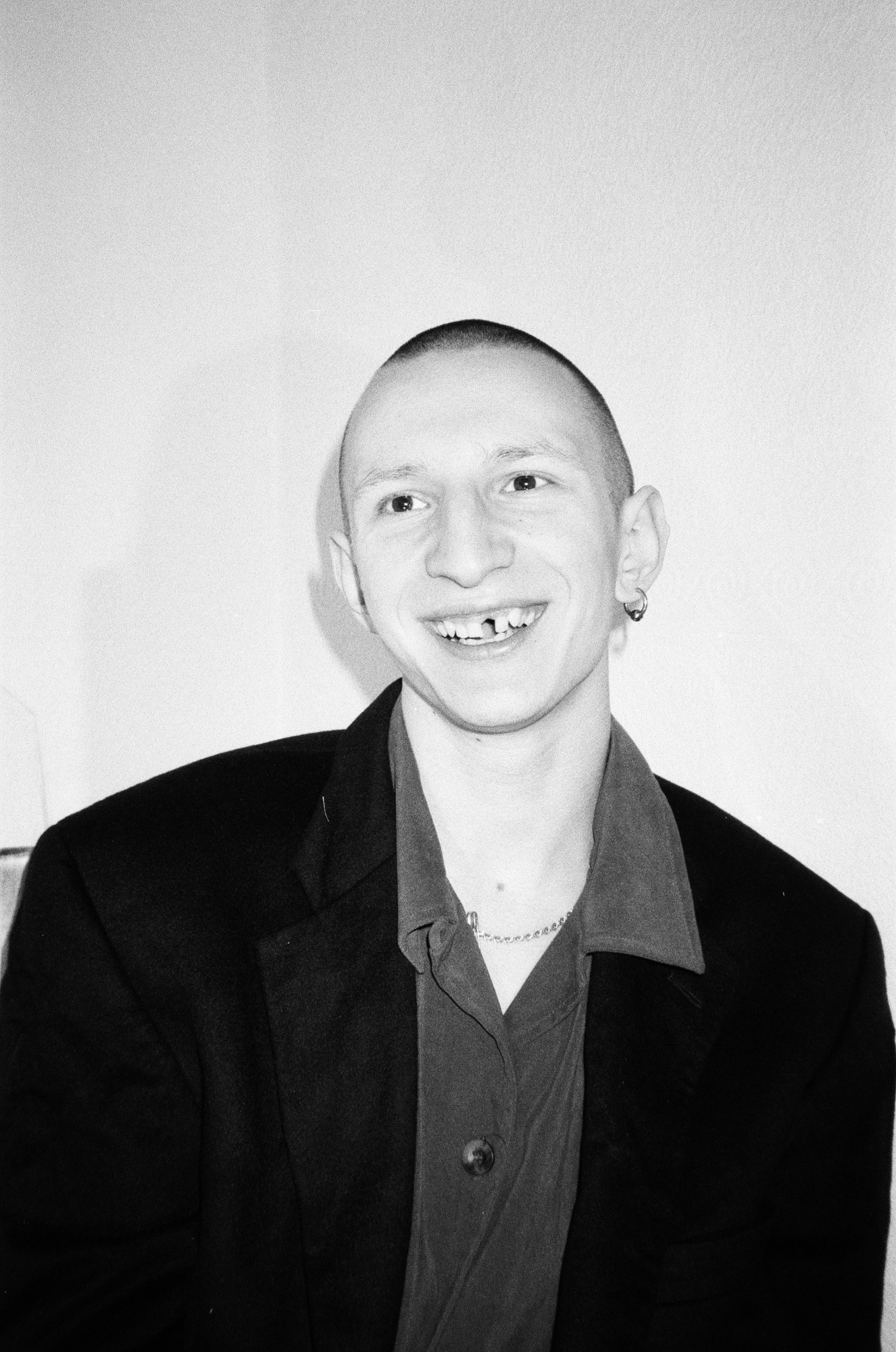

It’s almost all friends — it’s just me documenting my life. I always have my camera on me in my pocket. My friend Diana I met in rehab, and Dima, my tattoo guy, represent a kind of Slavic friendship — we can spend time together but do our own thing in silence. With French friends, we always need to discuss.

But many of these are new friends. Maybe because I feel more at home in Ukraine, and I’m more open there. In Paris, when I take photos, it stops there — we don’t see each other again. I met this couple, Sophie and Alexeï, via Instagram. I contacted them to take their photos. We drank tea, we smoked, we talked. They had a beautiful balcony outfitted with windows usually used in trams. I took unposed photos of them. They’re actually not together anymore.

I also met three guys during this trip, via Instagram — we followed each other and liked each other’s work — and we spent the whole two months together. Malek is an artist who paints; Ilya works with metal; Vlad was shooting a short film, and suggested I act in it. I don’t really know what it was about, but at some point we shaved each other in the bathtub. They all live in Kharkiv, but they came and stayed with me in an apartment I was renting. In Slavic countries, it’s much more open regarding strangers and staying with people you don’t know. We were going to do this film, so it seemed easier for them to stay with me. We got along amazingly, and have been close since. It’s just lucky. Some internet meetings, you forget about each other quickly. In this case, they just kind of followed me everywhere. I wasn’t doing well during this period. They held my hand and guided me, and I photographed them. Another friend was staying with me — someone I met in rehab—and he was shocked we all just wandered around naked.

How did you arrive at that point?

I myself didn’t have any period of adapting. The boys had known each other a long time, but it was the first time they got naked in front of each other. They were a little uncomfortable at first, but it was for ‘art’ — that’s how they justified it. They were observing each other’s bodies, discovering each other. It was very amusing to watch from the outside. I thought it was interesting to see friends reveal their nudity to each other. I mean, they don’t have a macho nature, but yes, there’s still something that’s instilled in them about ‘being a man’ from their families. But they’re already pretty different, relative to the masculine norm in Ukraine, with their colorful tattoos. They’ve been insulted in the streets with homophobic slurs before: they’re definitely on the margins.

But, very quickly, they were fine about being naked. It was really a friendly, easy-going spirit. They were like kids. A lot of people see these images as “trashy” or “provocative” — even a friend of mine called my work trashy once, and an exhibition review described my work as “Le trash poétique.” But to me, it’s much closer to childishness. There’s this fear around sex and sexuality. Nudity is a way of overcoming that, and photography acts as a kind of psychotherapy.

It can. Admittedly, nudity isn’t always as lived-in and uninhibited as it is here — it can be exploited through the lens.

Right. Here, though, they appropriate nudity for themselves! They’re at ease.

Which photographers depict nudity well?

Plenty, plenty, plenty. When I was younger, I was really inspired by Slava Mogutin, a Russian artist exiled in the US. He’s gay, and addresses his sexuality; he’s worked with Bruce LaBruce. I love what they do together — there’s lots of absurdity in it. I don’t know why I like it exactly, but I do.

What was the setting for all these images?

I rented this apartment that was really horrible, but good to take photos in. It was absolutely freezing: there was only this tiny, dingy heater in terrible shape, and the floor was gross. The water heater had a life of its own. The apartment was a two-story loft. Its grossness was almost charming, in a way. But after a month, when the boys left, I moved to my grandparents’ place. And we also went to Odesa for one of the boys’ art shows. We rented an apartment and were five people in two beds. The artworks didn’t arrive on time, so Malek made new ones and then burned them in a performance.

What is the present status of the people in your photos?

One is a refugee in Paris. Ilya and Malek didn’t know Alexei, but after the met through me they are staying together in Lviv. For now, it’s safe; they’re creating art. They have no military history, so they haven’t been summoned for duty. They’re not worried about that — but they’re worried about money. I send them money from time to time. There’s no work. They live from day to day — they live in the present. I live in the future or in the past, but certainly never in the present the way they do.

My dad has been summoned for duty. He sent me a funny photo showing his battalion [on her phone, extends a photo of a horse and cart]. My grandparents are together. My grandfather does a kind of neighborhood watch with his Rottweiler in Kyiv. Everyone is quite positive — or, at least, they’re positive in what they tell me so that I don’t worry. Part of me has trouble believing the whole thing. It’s taking me time to process. I think I won’t truly realize it for a while. At first, I was following everything, but now I mostly just wait to hear what my friends and family are telling me.

Which Ukrainian photographers do you follow on the ground?

I follow a group of girls who created an organization that supports the soldiers, started by a Ukrainian photographer, Kris Vóitkiv. And I follow Nazar Furyk — I like what he does, it’s really brut. But I mostly follow my friends in Ukraine: I watch their stories — although they don’t really post about themselves anymore. And all I know is: as soon as I can go back, I will. To see what it’s like and, of course, to take photos. Maybe this will become a longer series: before, during, after.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more photography.

Credits

Photography Sofiya Loriashvili