On the evening of 4 April 1988, a then-22-year-old Norman ‘Normski’ Anderson was backstage at London’s Brixton Academy, primed to take pictures with his compact camera. It was one of the biggest, most anticipated nights in the city’s hip-hop calendar, as powerhouse crew Cold Chillin’ – featuring Big Daddy Kane, Biz Markie, Roxanne Shante and MC Shan – had touched down in the UK’s capital. As they emerged from their dressing room, their tour manager saw him, and approached.

“Oh, who are you?” he asked Normski.

“I’m a photographer.”

“Oh yeah? What are you doing tomorrow? We got a gig somewhere else in England, do you want to come and take pictures?”

Without hesitation, he agreed. “He probably looked and thought: ‘There’s a motherfucking Black guy with a camera – you never see that shit,’” Normski says, remembering the moment. “I went home thinking: ‘I’m going on the tour bus, yeah!’ And then when I got on the tour bus, they all fell asleep – they got jet lag. Roxanne Shante is sitting there sucking her thumb, Biz Markie is asleep and I’m sitting opposite Big Daddy Kane, [he’s] fast asleep. I took a couple of snaps anyway.”

Now, over three decades later, those pictures he took – of the iconic rappers peacefully dozing with their heads against the tour bus windows, and Roxanne with her head on the table in front – are published in Normski’s debut monograph The Man with the Golden Shutter. Having first picked up a camera aged 12, immersing himself in London’s underground music scenes soon after and thousands of gigs and parties, the book is a deep dive into the broadcaster, DJ and photographer’s extensive picture archive between the mid-80s and early 90s. In that time, he was front-and-centre documenting with his camera, as hip-hop – then jungle, 2-step, and techno – burst from nascent, fringe music genres into the mainstream consciousness.

Music photography came naturally to Normski, who drummed in a band and became obsessed with taking pictures in his early teens. While his contemporaries were building home studios, he was drying prints in his parents’ bathroom. Simultaneously, across the Atlantic, funk music was becoming infused with break beats and lyricists began rapping over it – led by DJ Kool Herc’s pioneering mixing of records 50 years ago – and a cultural, musical and fashion movement exploded onto the streets of New York and beyond.

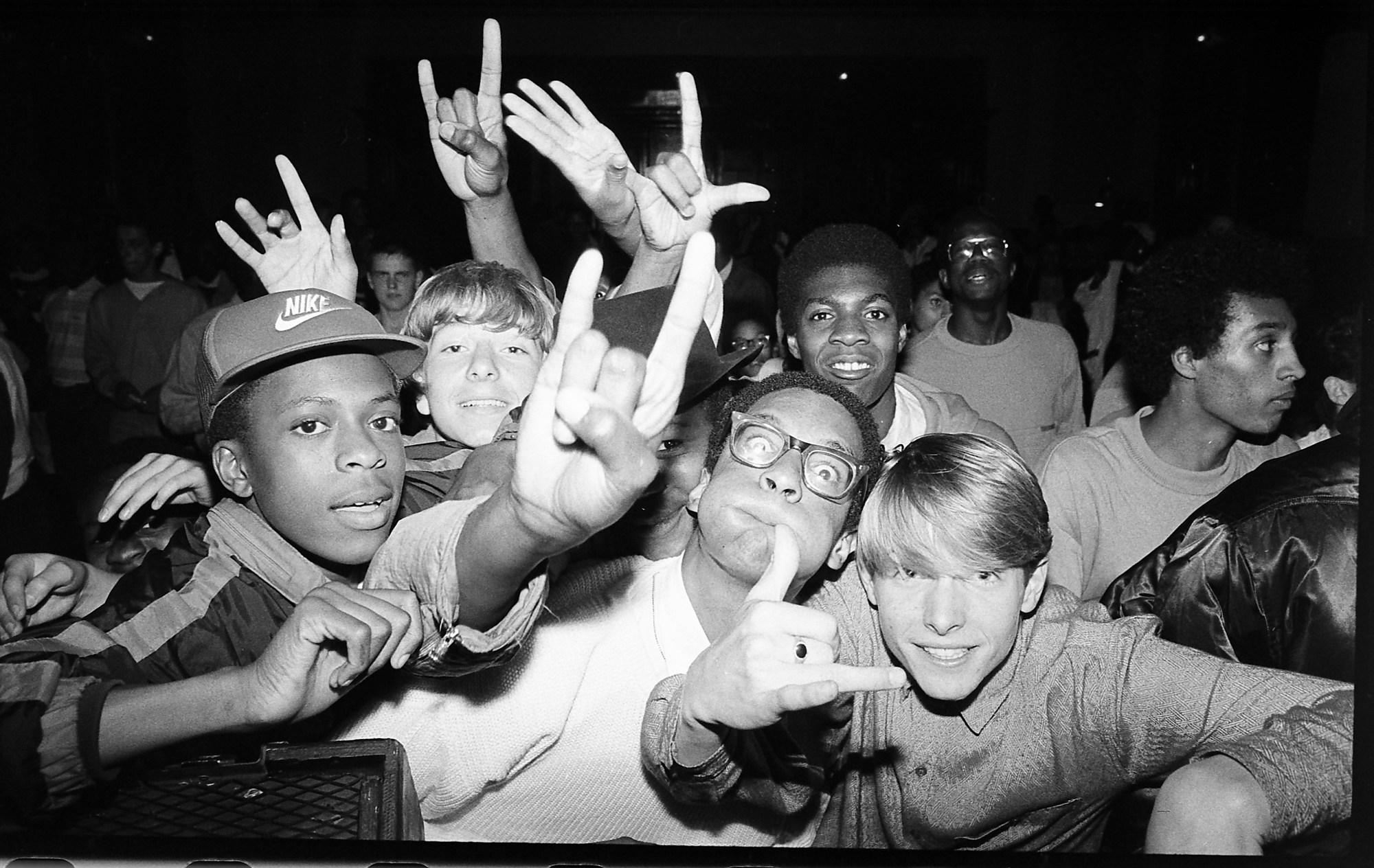

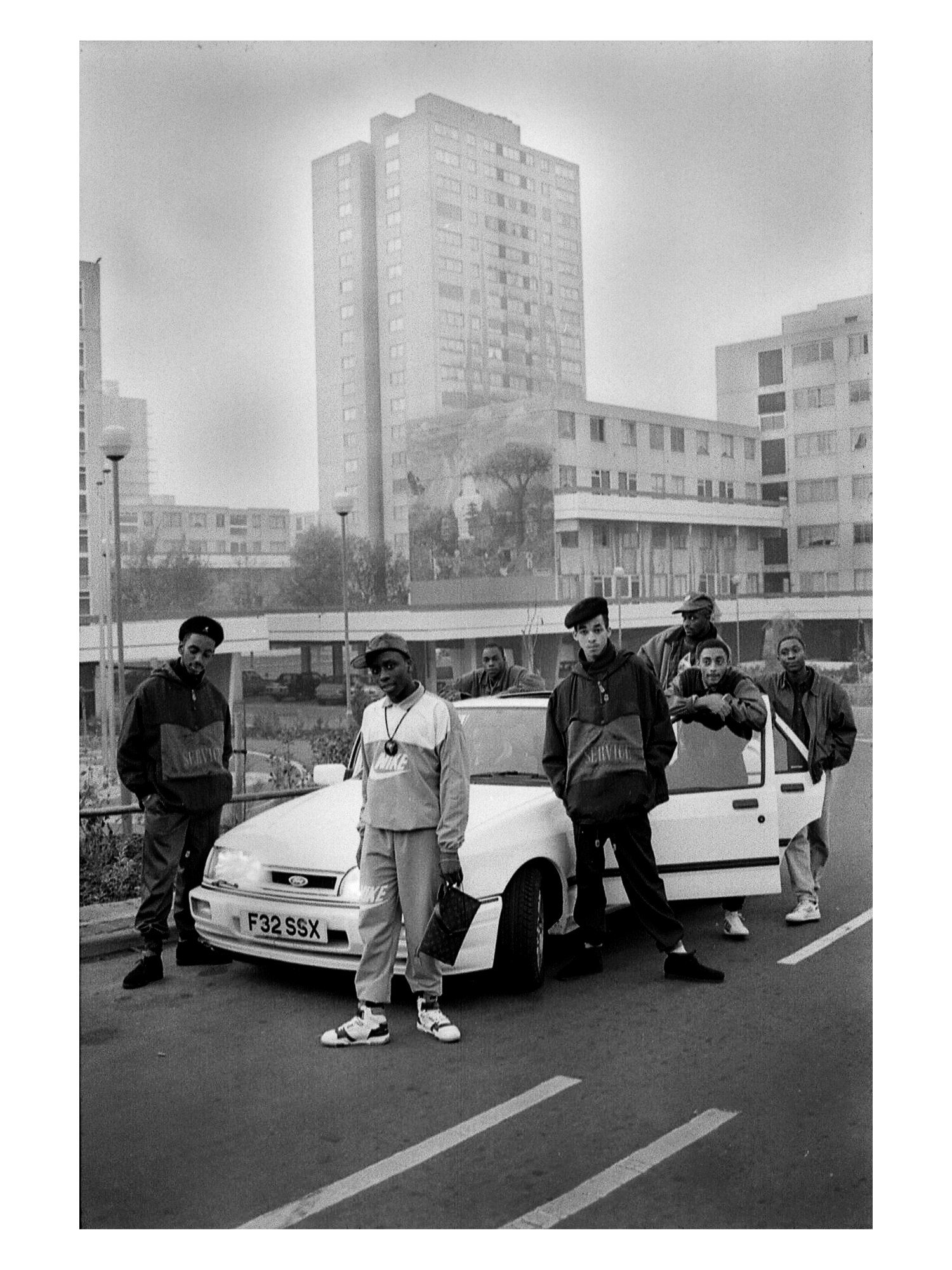

Hip-hop soon reached London, where its breakdancing and beatbox-powered loudness was initially met with apprehension and side-eyes. “There wasn’t a lot of space for this new scene,” Normski says. “When you saw it, it was mostly bad press at the beginning… kids just being on the streets – they thought you should be at school or at work. [But] it was young people on the streets, hanging out on corners doing these crazy dance moves on the floor.

“They were carrying kitchen lino around to put on the floor so they could spin on it – it was like an outdoor club that didn’t have a home yet. It was unusual for this country to see this new activity.”

Normski, though, was drawn in by the culture’s vibrant spirit, and he would bring his camera to shows, taking shots from the crowd while pushing his way as close to the stage as he could. But what started out as a hobby and obsession became a way of making a living after a chance conversation with Ray Edwards, who worked for one of the biggest music promoters in the UK. Ray immediately took a shine to the young photographer, and helped him gain the access that would kick-start his career.

“He said ‘Oh, you take pictures? Well, if you’re any good at this you could do really well,” Normski recalls. “‘We can’t pay photographers, but what I can do is get you a photo pass. Go and sell the pictures to different mags’.”

So that’s what Normski did, soon becoming a familiar part of the scene, shooting for music magazines like Melody Maker, NME and Hip Hop Connection. At the latter, he was given two pages at the front of the mag titled ‘The Man with the Golden Shutter’ – the inspiration for the book’s title. A newly-founded i-D became one of his most regular landing spots, after he burst through the doors of its Covent Garden office one afternoon riding his bicycle. The magazine’s former fashion editor, Beth Summers, and founder Terry Jones “were very trusting friends who believed in me”, he says, “who gave me an opportunity to do my fucked up shit in a magazine about fucked up shit”.

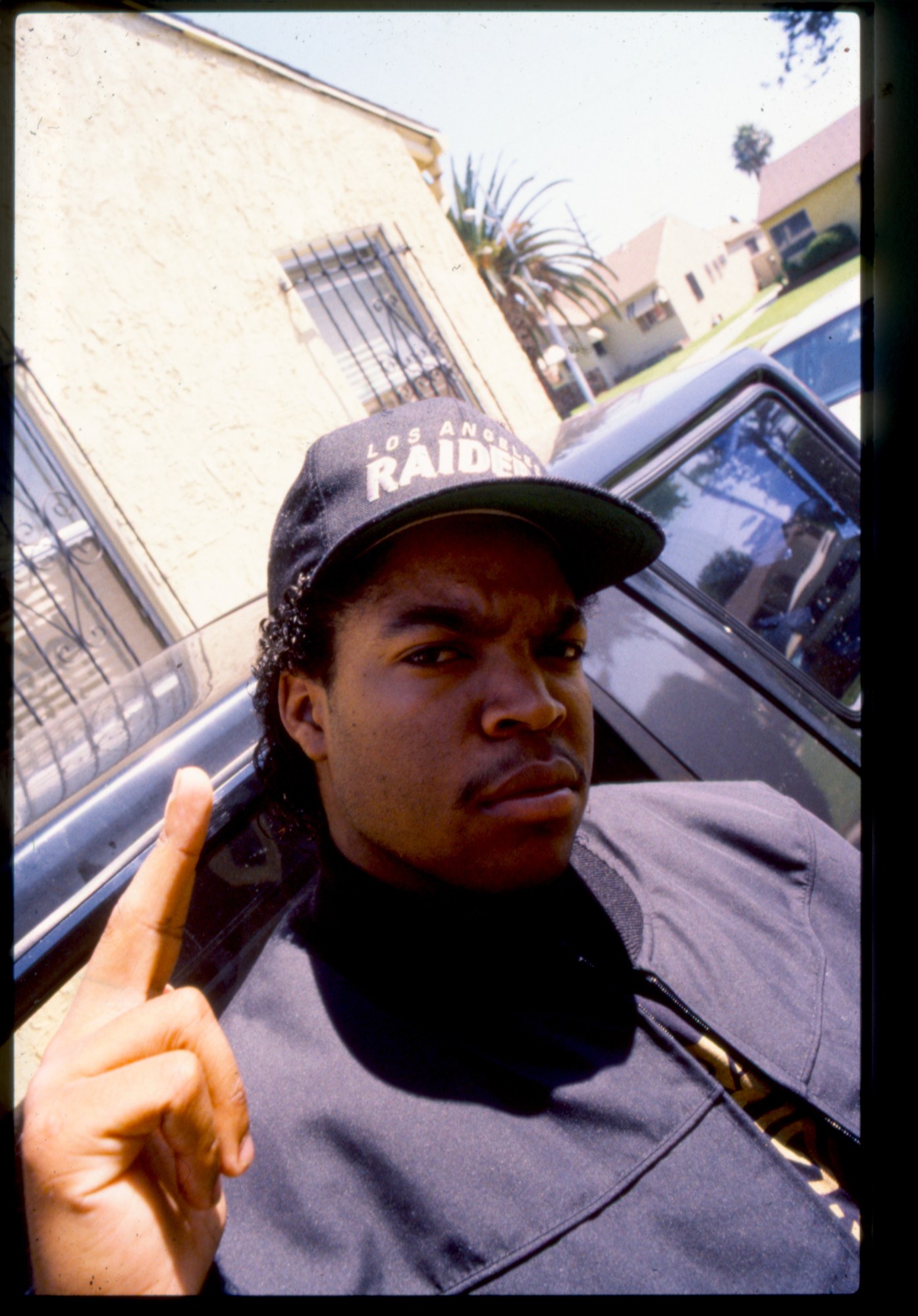

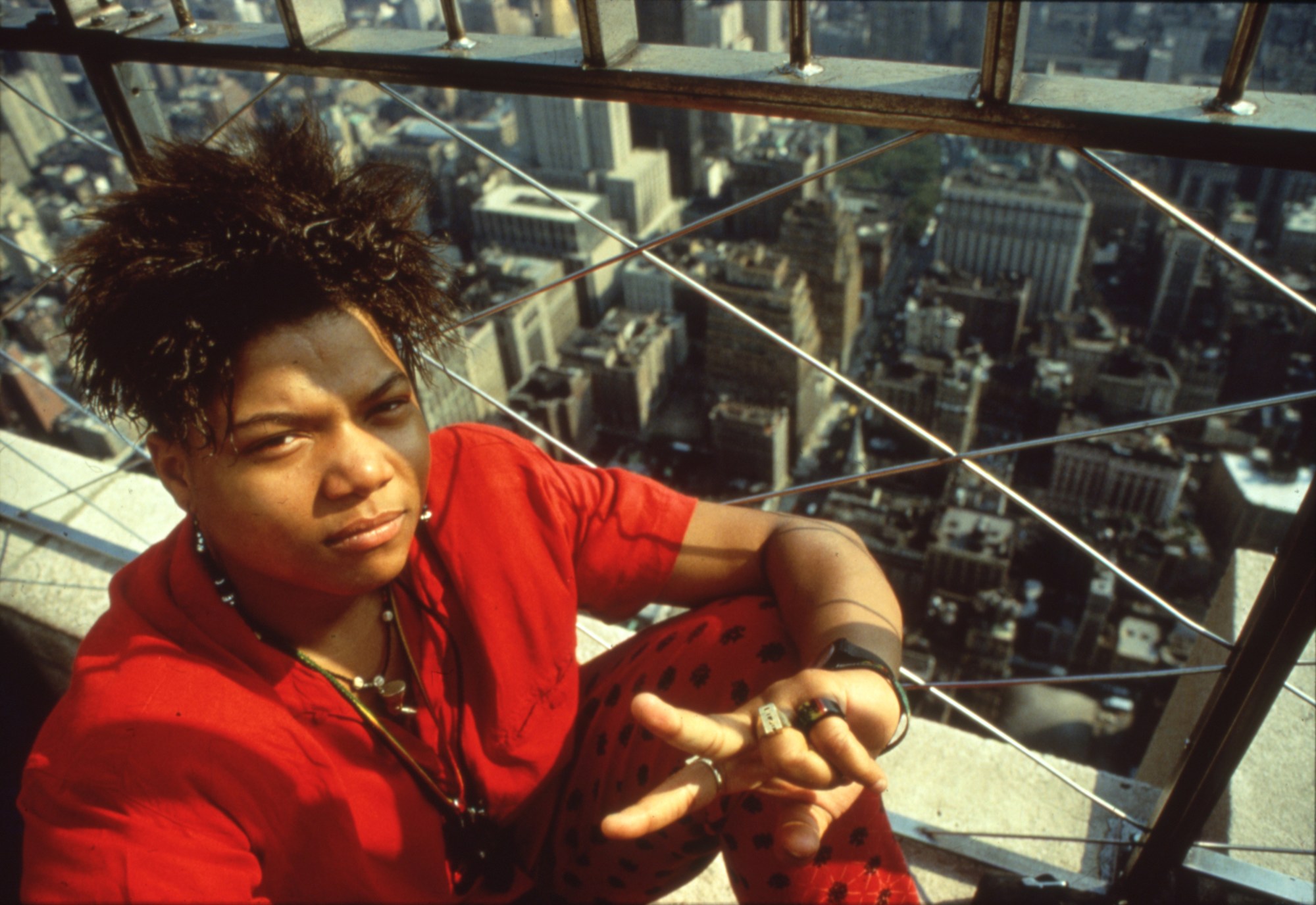

The photobook features a diverse array of his work from the period, including several portraits he took for magazines. There’s up-close-and-personal action shots at gigs, record sleeve covers, snaps of legendary DJs going head-to-head at afterparties, and candid pictures of legends hanging out away from the stage. Stars of the era like Big Daddy Kane, De La Soul, NWA, Flava Flav and Run DMC all feature, alongside all-female London crew She-Rockers and UK-scene stalwarts Hijack. “Anyone who knows about UK hip-hop particularly knows the names Hijack, MC Duke and Demon Boyz – oh man, these guys are fucking trailblazers.”

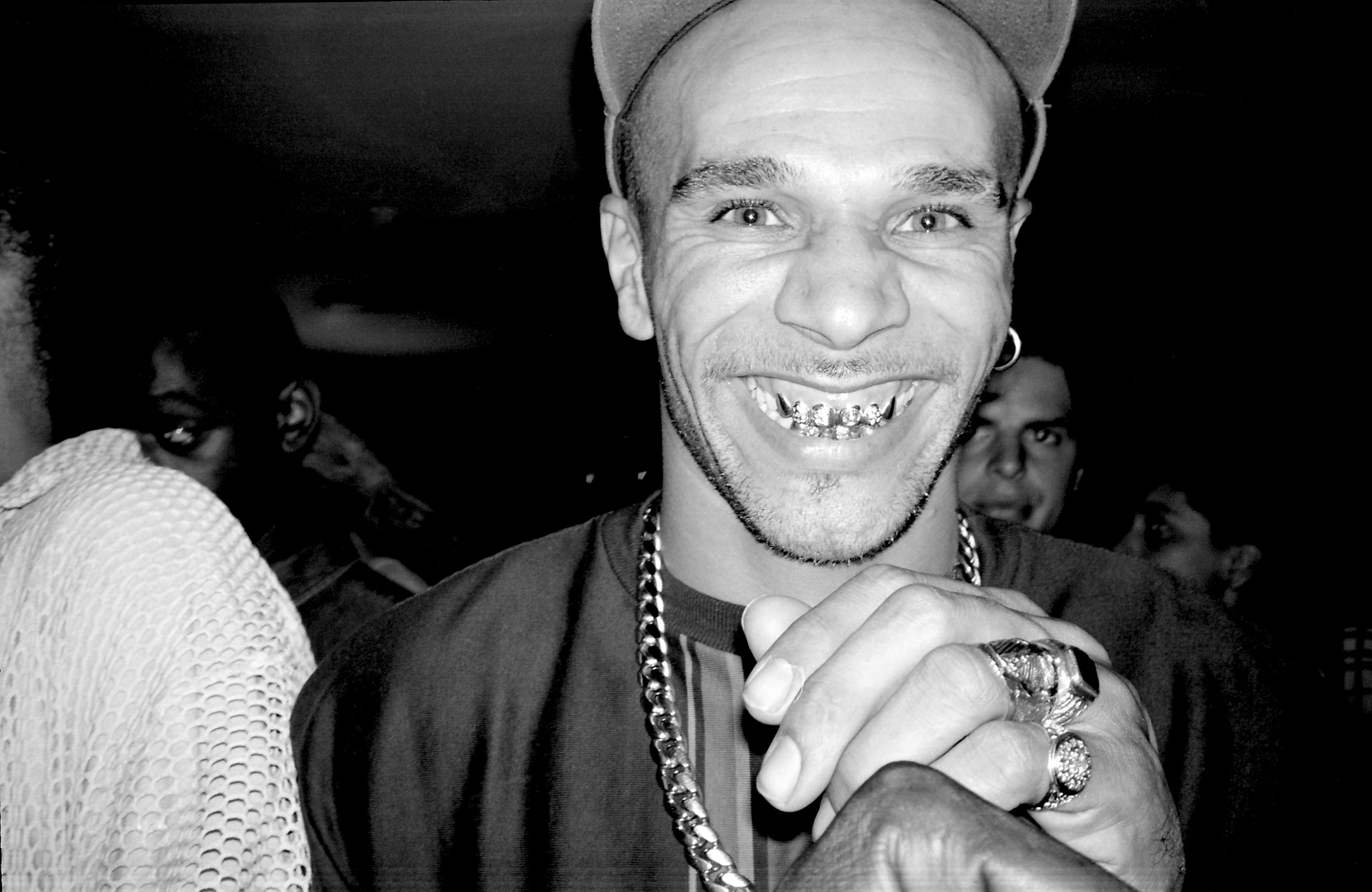

Time spent in the US, and a trip to Detroit saw him become the first Black photographer to snap the techno originators The Belleville Three, while drum & bass pioneer Goldie also makes appearances across the book’s pages. But among all the legendary artists featured, and the history documented in each shot, perhaps what shines through the most is the intimacy of Normski’s connection with his subjects. As a young purveyor of the underground, he captured the stars before the bigger bucks came calling, and their public images became tightly curated.

But it’s also testament to Normski’s own creative methods and personality. He’s an engaged talker and listener, which behind the lens translates to an uncanny ability to help the artists he works with relax. “I want to know what makes you feel good, where you hang out when you’re on your own and just want to get away from the world. When you’re in your element is where I want to be. And I think a lot of people are like ‘Fuck, I love this guy’, because it’s not work, [I’m] making it a bit of fun.”

While Normski would eventually move away from photography in the early 90s, he took that same personality in front of the camera, as he hosted BBC2 music and culture show Dance Energy, while also moonlighting as a DJ. It’s been a diverse, influential career, and now decades later, the book’s release is an opportunity to reflect on a vibrant period. “It means everything to me. I’m finally able to share a lot of experiences that I was blessed to have,” he says. “All these moments, together, so you can really get a feeling of what the fuck I’ve been through.”

Normski: The Man with the Golden Shutter is published by ACC Art Books

Credits

All photography Normski