In 1979, after a long day of shooting the biggest stories of the day for the New York Post, Martha Cooper would drive through Manhattan’s Lower East Side. On this trip back to the office she would typically use up the rest of her film on whatever caught her eye. Charmed by the “kids being creative” in the city, she created Street Play.

One day while working on Street Play, Martha came across a young graffiti artist who went by the name of HE3; she photographed him on a tenement rooftop, caring for his pigeons. He showed her his notebook, and an elaborately sketched “HE3”; he explained that he was practising how to spray it onto a wall.

“Until that point, those unintelligible bunches – like DAZE or DONDI – didn’t make sense because you expected graffiti to have a message,” says Martha. “I didn’t realise kids were writing their nicknames. Once I understood that what I was seeing were individual names, seeing graffiti became like a treasure hunt.” What started off as a hunt soon became a passion. Her encounter with HE3 led to her meeting the now-legendary artist Dondi White aka DONDI, who told Martha about the vast array of graffiti that goes unnoticed, just below the surface of what typically meets the eye.

“He kept talking about these big pieces I had never seen,” she says. “Top to bottom, whole [subway] cars – and I had no idea what he was talking about. I had never really looked at the outsides of trains.” Martha decided to go and see if she could catch a glimpse for herself, travelling uptown to 180th Street in The Bronx, where she knew that the trains passed above ground. “The first time I went, the ‘LEE’ [painted] train with the poem on it was sitting there,” she says. “It must have been freshly painted the night before – it was my very first day of looking.” Excited, she returned the next day, where a fully painted carriage tagged with “BLAZE” passed by, most of its windows still marked. Now on a roll, she drove up and down the tracks looking for places to shoot passing trains – an activity that would lead to her quitting the Post in 1980 in order to pursue it full time over the next few years.

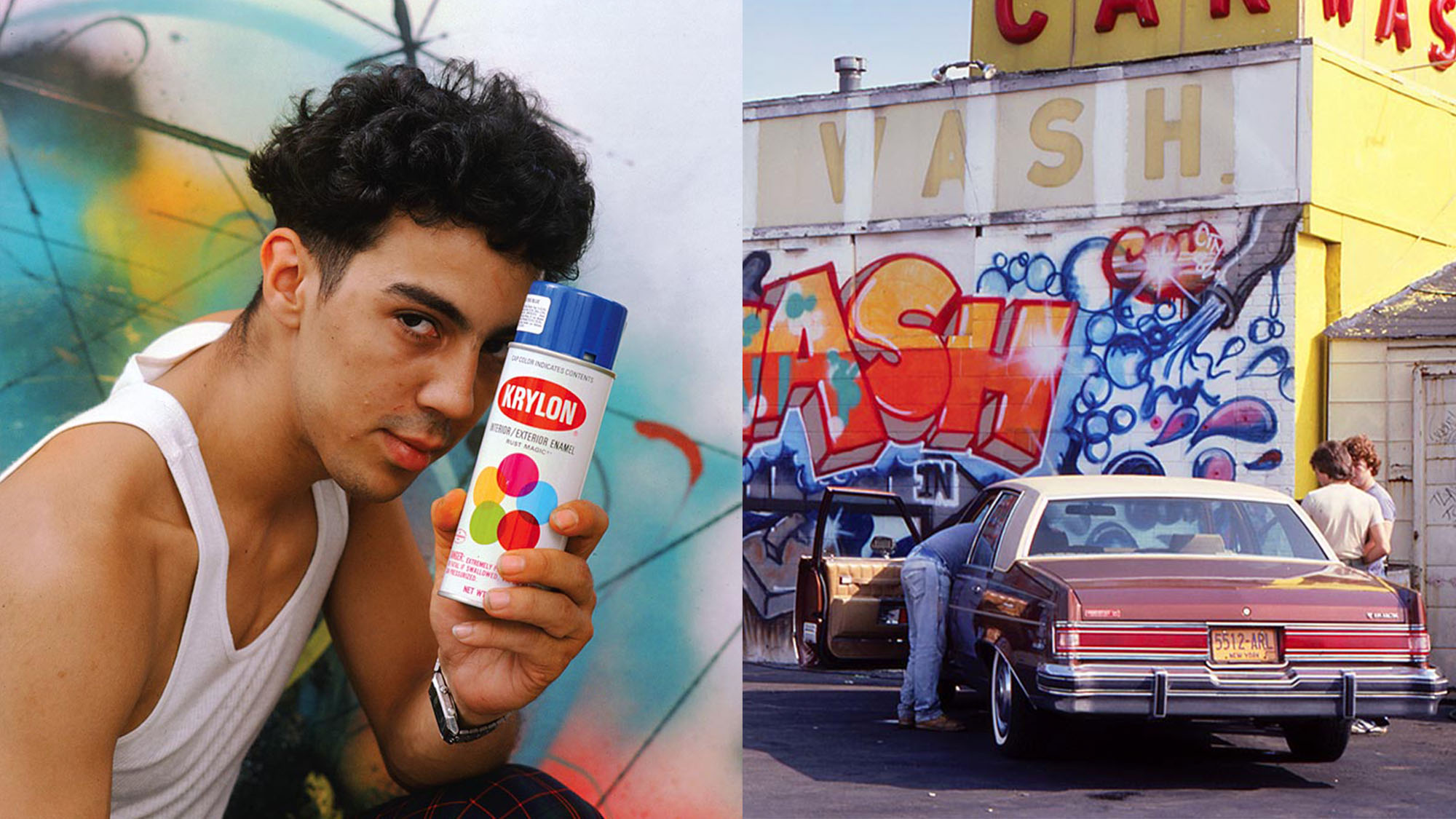

The soon-to-be published photobook Spray Nation compiles hundreds of Martha’s photographs of New York City graffiti in the first half of the 1980s, splashed predominantly across and inside subway cars and stations, but also other aspects of the urban jungle: buildings, signposts, and metal railings. Her photographs capture the distinctive and iconic style of underground graffiti at the time – in-your-face colourful, intricate and calligraphic – which has gone on to inform movements and styles across the world.

What is perhaps most evident, however, is the underlying sense of fun in the graffiti. In a young scene, the excitement, as well as playful rivalry between artists, comes through in the works and shots of writers that she captured. “It’s an art competition that takes a lot of skill,” explains Martha. “It takes a lot of planning to pull off a great piece at a great spot, and that adds to the excitement.” But it was also incredibly fleeting. Large, extravagant pieces of graff could be scrubbed clean or repainted overnight. Martha’s photographs have helped to preserve them in time. “Photographs were always important to graffiti writers,” she says, adding that she would give them small prints of pictures she’d taken of their work. “The photos were proof of their actions.”

Her dedication to documenting the graffiti led to her flipping her day job working hours to night shifts. “I was able to switch my hours so I could go up and watch trains in the morning, because rush hour was the best time to catch the trains on one side and afternoon on the other side,” she says. “I wanted to shoot so the sun was hitting the train – not backlit.”

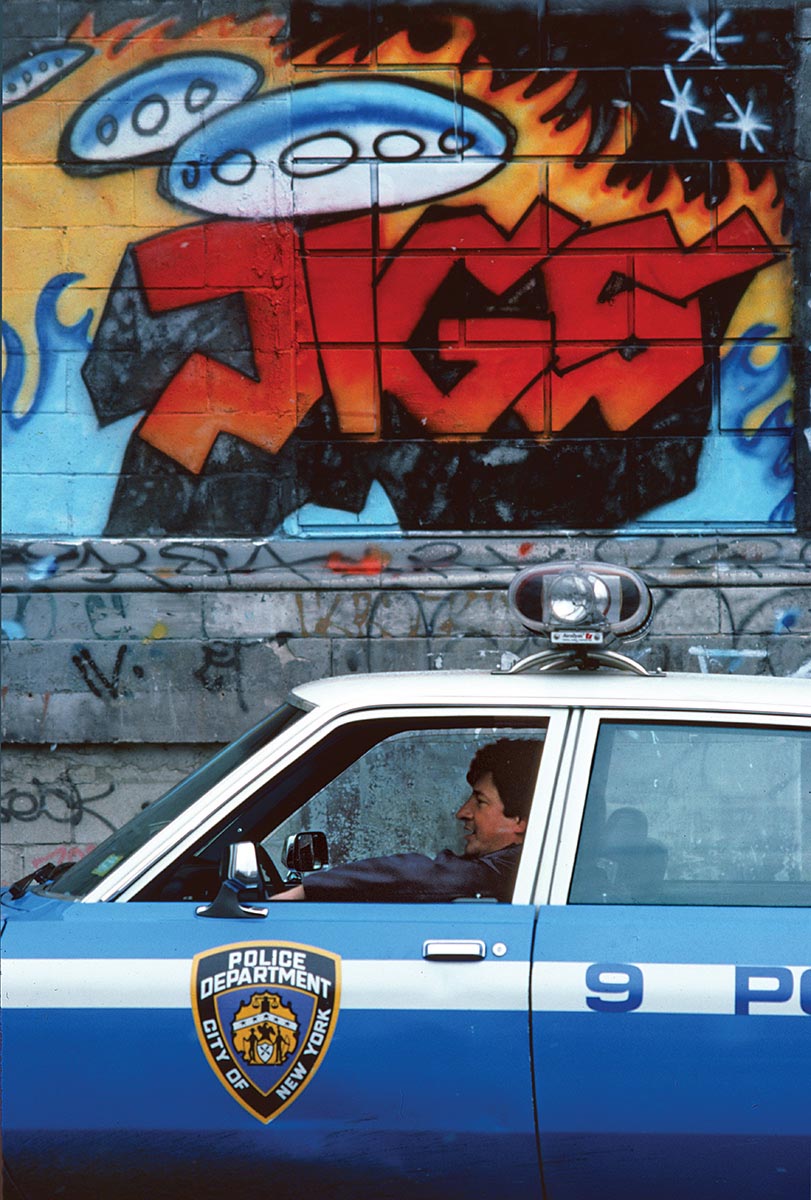

It also led to her searching out new, and often sketchy, places to shoot. She often clambered into fenced train yards or hung around parking lots in the middle of the night, hoping a sprayed subway car would pass for a shot. “You never knew what you were going to run into in the yards,” says Martha. “There could be cops or rival writers. It could be dangerous – you might get beat up or arrested. I never knew if I would be protected as a journalist.”

While she never had any run-ins with the law herself, by the mid-1980s the authorities had started to clamp down on graffiti tagging, and the artists responsible. By 1985, New York City was spending $42 million a year on graffiti clean up, often taking trains out of service immediately if they had been tagged, only returning them to service once every inch of spray paint had been scrubbed. This, plus tougher policing and more stringent security, put the brakes on a once-thriving scene.

The drop-off came around the time of Martha’s first photobook about NYC graffiti – Subway Art, a joint project with fellow photographer Henry Chalfant – was published. Now considered a classic, and often referred to as the “graffiti bible”, the pair initially struggled to find a publisher, and once they did, many retailers refused to stock it. “When the train painting stopped, there was a lull,” Martha says. “There was a feeling something had been happening but somehow it flatlined. I imagined there would be a reaction when the book was published but there was virtually none. It was so disappointing.”

Yet in the decades since, the movement has turned into a worldwide phenomenon, as graffiti came to be seen in many of the world’s major cities. Legal street art has also been embraced by many metropolitan authorities, and works by big name graffiti artists continue to sell for millions of dollars. “In the early 80s, the scene was primarily NYC-based and very underground,” says Martha. “I thought it was a New York phenomenon that couldn’t happen anywhere else. I thought it would disappear – wrong!” Despite this, she still sees flickers of that 1980s underground spirit in today’s artists. “Berlin’s 1UP Crew are the epitome of urban adventure. They painted in a subway station with fire extinguishers loaded with paint while the trains were still running and there were people on the platform.”

“Illegal graffiti is super exciting,” she adds. “I understand the attraction.”

‘Spray Nation: 1980s NYC Graffiti Photographs’ by Martha Cooper, Edited by Roger Gastman © Prestel Verlag, Munich · London · New York, 2022.

Credits

All images © Martha Cooper