Bel Cobain says her music has lacked consciousness until now. Even though the grippingly emotive lyrics of her most popular tracks: “At The Bay,” “Leader” and “Introverted Stoner”, do much to synthesise how many of us feel. She writes relatably about her mental health, the complexities of relationships and her daily life, with one song even asking the age-old question: where’s her phone charger? Six years on from her first release Mint in 2018, Bel has collaborated with the East London initiative, The Silhouettes Project, on their 2020 album that united more than 30 rappers, singers and producers, and become a fixture in London’s new wave jazz scene. She’s acutely aware people are listening and knows it’s vital that her new EP, Radical Forgiveness, has a message. “I’ve used music as a crutch or as a gateway into something, and I just want to be responsible with that gift,” she says.

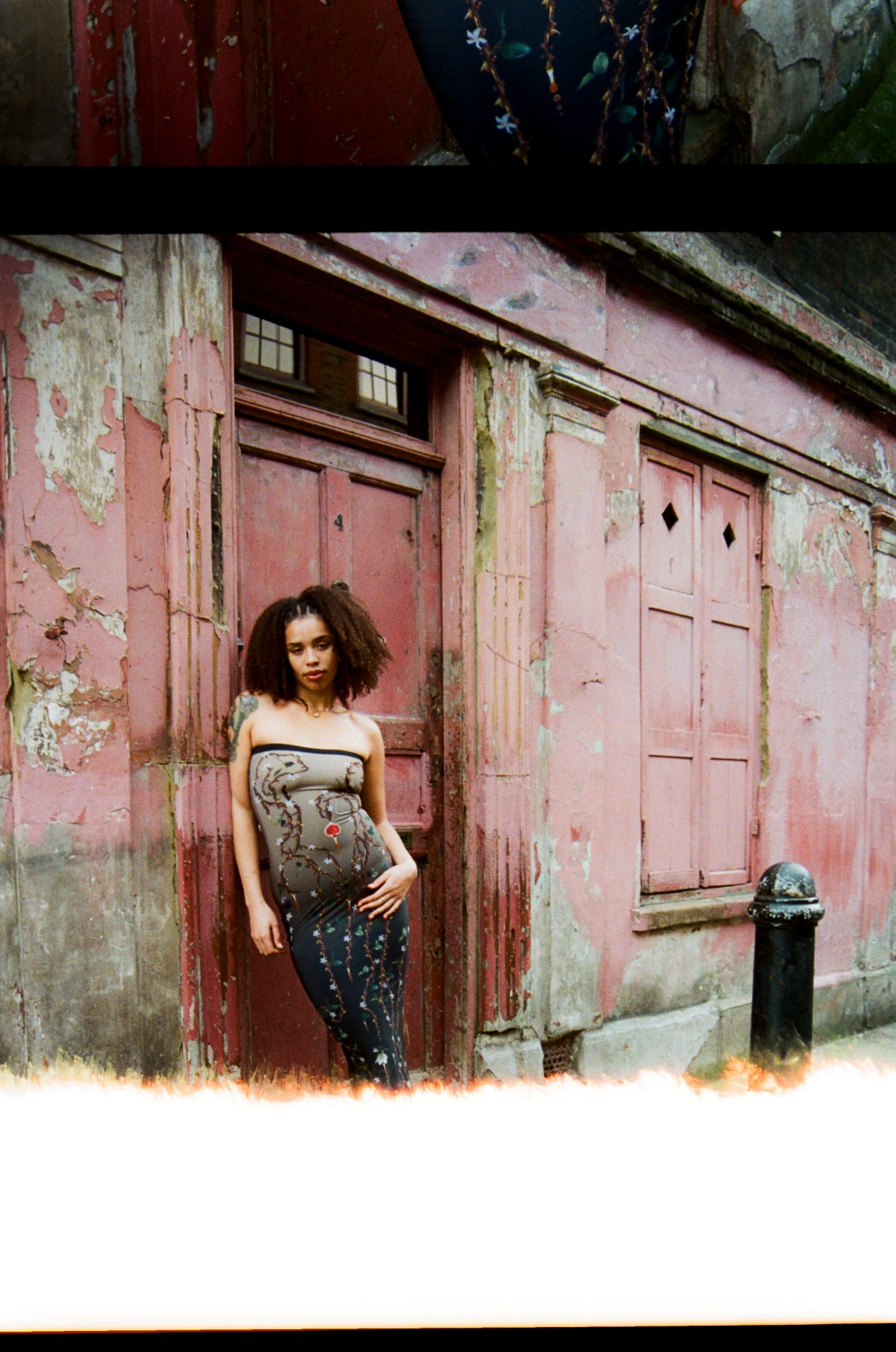

When we meet in Shoreditch on a sunny November day, a couple of streets over from where she lived during the pandemic, Bel exudes warmth. She flicks her hair back and forth with a vulnerability that disarms an abundance of confidence. She’s articulate and poetic, much like her lyrics, but the 22-year-old Londoner is also outraged: “There is no sense behind this world that we’re living in.” She’s thinking about Israel’s ongoing bombardment of Gaza and a war in Ukraine, among other conflicts. “How the fuck, on one side of the world, can the worst atrocities be existing and simultaneously, we’re sitting in a coffee shop having a laugh? All of our families are at home safe.”

“One brain cannot quantify the reason for life when those two things are going on,” she continues. Written earlier this year, her song, “Worldly Bliss”, tries to make sense of it all. It opens with haunting synthesised vocals that sound almost like the morning call of a bird, while she raps: “No need for the mindless weapons/ they make in a blink of a second/ and call this heaven/ How can I question this?/ Worldly bliss.” She reflects on her privilege — why does she deserve to be warm, fed and safe while others do not? “I’m not ready for this minefield,” she sings, “we live but you die slow.”

Following in the footsteps of artists like Kendrick Lamar, who she calls one of the “modern greats,” Bel is dedicated to building a collection of EPs before she releases her first album. “I like the idea of that freedom before you say to the world, ‘I’m ready to give you a message’. When I say ‘radical forgiveness,’ I’m not there yet, it’s just something I’m exploring,” she explains. Bel wants the EP to feel like a journey: the main single, “Pressure to Exist”, is soulful and rootsy and depicts the artist as a victim. “Unlikely” is much more jazzy with a drum and bass rhythm throughout, while “Worldly Bliss” and “Came Over Me” distil alternative R&B and hip hop. The last song “Awakening”, is a lighter dance track that encourages the listener to move, and for her to move on.

“Pressure To Exist” is an ode, Bel says, to a time when she fell ill and “didn’t know my left from right anymore.” It was her last year of school, and she’d been studying hard to become a doctor, but suffered from a mental breakdown and was diagnosed with psychosis. She ended up being homeschooled by the council and sat her GCSEs, but the last thing she was capable of doing, psychologically, was go to university. Instead, she went to study animal management and graduated with a BTech in horticultural sciences. She found solace in nature, which became a lifeline for the singer.

This past year, Bel’s spent a lot of time connected to the earth: trading in the red-bricked streets of Hackney for the wild sea of Folkestone in Kent at an artist’s residency. In March, she travelled to Mexico, where she spent time between Mexico City and Oaxaca. She’d been to the country before, and stayed on a tiny island off Puerto Escondido called Chachua, where she was inspired by the boldness of its people and the untamed creativity.

She wrote “Unlikely” between Mexico City and Oaxaca to reflect on a series of spiritual “not connections, but more like invasions” she felt there. “We were haunted,” she says. One day, Bel’s friend went out to get some chocolate and came back home with none. He said, ‘I’m not going back out there again. I saw a woman that was not a woman. She was standing outside a shop, looking at me madly, like you shouldn’t be here, and then walked through a wall.’” Bel tried to capture the intensity of what was going on with the song’s hypnotic baseline, playing the beat again and again during her stay at an artist’s house. “The lights turned off and I felt a brush against my cheek, and I looked at my friend and he’s brushing something off his face as well,” she says.

Bel wrote the lyrics in the two weeks she was there, and still finds it hard to believe that they came from her own experience. In the song, she also reflects on the colonial genocide of Indigenous peoples across Mexico, where hundreds of thousands of Apaches, Mayas and Yaquis were brutally murdered or forcibly converted, with their knowledge and practices almost entirely wiped out. “I feel sorry for my people/ who got rigged by the systematic default,” she sings, contemplating the after effects of Spanish rule on the Indigenous people who, she says, cannot maintain wealth anymore.

Bel often straddles the line between the academic and the spiritual. It helps her “merge colossal feelings with the academic essence of science”. “Spirituality is just one step from science. In science we learned that energy is never lost, it’s only borrowed and transferred. It’s completely connected with the physicalness and the manifestation of things and understanding how we all interrelate,” she says. “The moment you completely surrender to that, that’s when you can start doing magic and manifestation because you’ve surrendered from your attachment to these things.”

After her breakdown, Bel really lent into her spirituality — needing to believe there is something bigger than her. It correlated with her making music and looking at the natural world in a serious way. “[Nature] really gave me physical evidence for being alive because nothing’s perfect,” she says, pointing to a plant: “This fucking thing in here, it’s trapped by that stupid pot. When you go to Mexico, you see them in their natural environment. That’s a bit of me. I was not planted in big enough soil when I was younger and now, as an adult, I can choose where I want to be and put my roots really far.”

Bel grew up on Pembury Estate, a series of 1930s walk-up blocks in Hackney Downs, with her mum, who used to play a lot of progressive and psychedelic rock. That ilk of music had political elements to it, she says, with bands like Pink Floyd proving to be formative for the singer. She was also dragged on marches for much of her childhood: “back when Tony Blair was doing his fuckery.”

Radical Forgiveness is Bel’s attempt at telling the world she cares. “I don’t just want to be a pretty face with a voice,” she says. “I want to make sure that if there’s anything I leave, it’s a clear message for people to wake up, smell the coffee and do something about it. I’m on radical energy,” she says. “Maybe not always radical forgiveness, but radical energy.”

Radical Forgiveness is out now.

Credits

Photography Milo Matthew