“Can you hear the chicken?” Brazilian photographer Rodrigo Oliveira asks over Zoom with a smirk. He’s in his childhood home in Barra de Guaratiba, a seaside suburb of Rio de Janeiro about 30 miles to the west of the city. The chicken crowing in the background comes as little surprise: Rodrigo’s rural surroundings often serve as the backdrop of his moving and tender portraits of Black queer folx. It’s the perfect setting for an artist interested in life on the peripheries of geography, race and sexuality.

“My photos of the Black community are mostly in [metropolitan] Rio,” Rodrigo says. “If I photograph with a connection to the ocean or there’s a beach setting, it’s definitely here [in Barra de Guaratiba]. That’s when I’m bringing my friends over, or sometimes I want to have a date and I end up photographing the person. A lot of the time I’m with my partner, and I take a lot of photographs here with him.”

After a long stint studying biology in Australia and Germany on scholarship, Rodrigo started his portrait work when he returned to Brazil, the pandemic keeping the young photographer in his home country for the first time in years. An initial interest in conservation served as the incubator for his interest in photography, but he was looking for something more important when he returned to Barra de Guaratiba. Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement and Civil Rights Movement, he set out to document the Black queer community in his suburb and in the favelas of Rio.

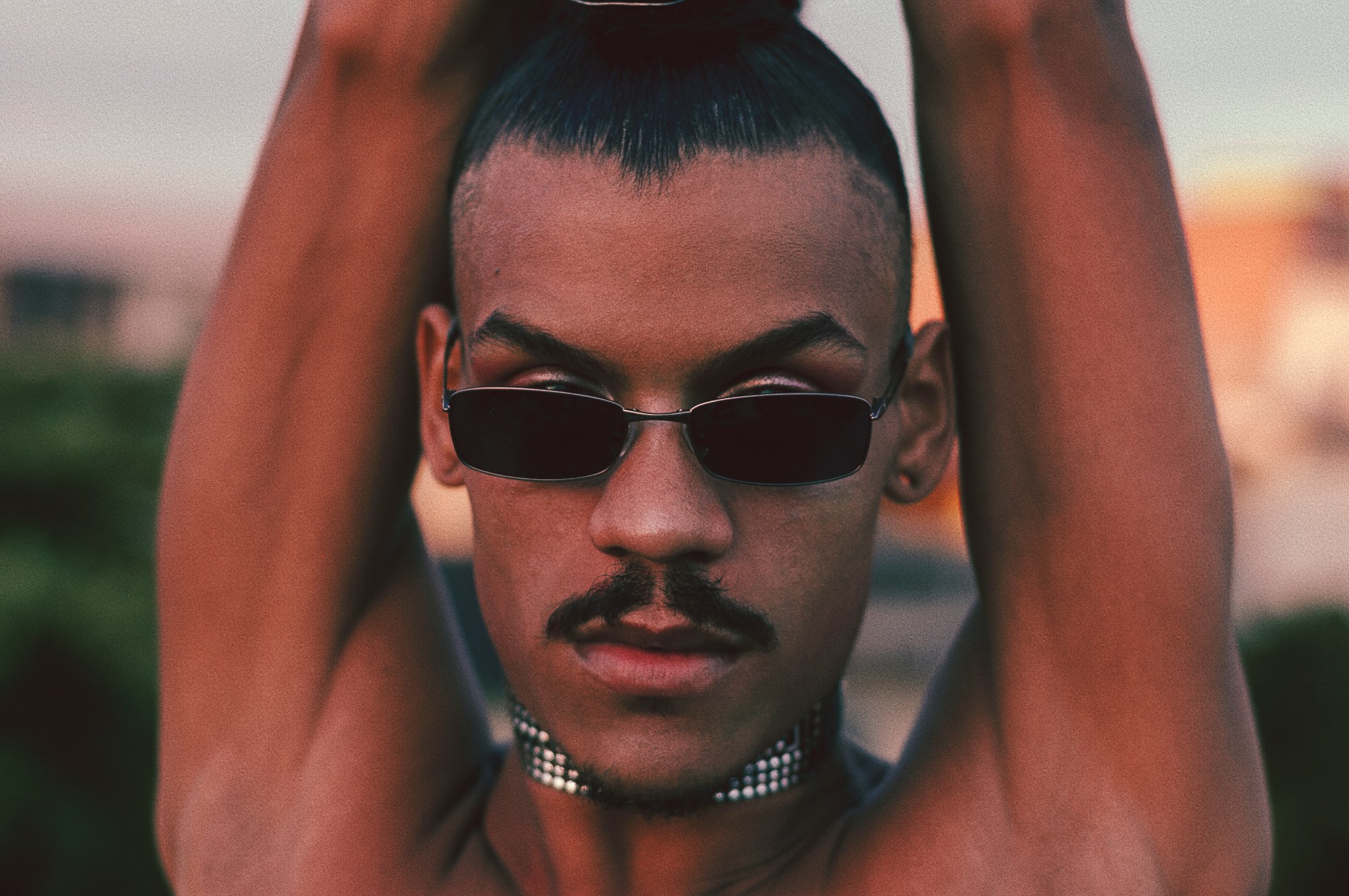

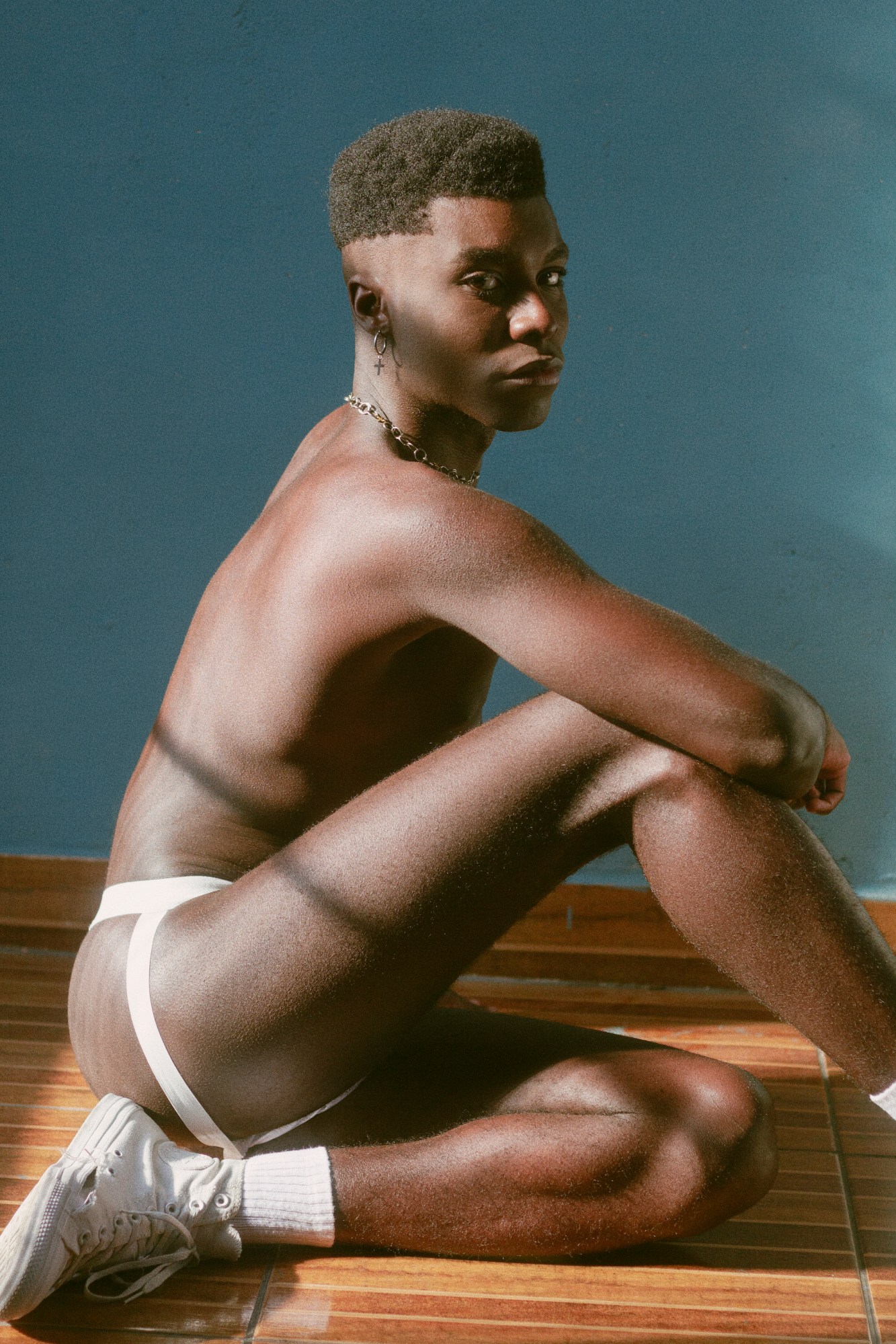

The resulting photo series, titled Carioca, Negro, Queer (Carioca, meaning someone from Rio, Black, Queer) is as much a document of joy as it is a site of resistance. In the face of Jair Bolsonaro’s notoriously anti-queer and anti-Black political reign, these warm portraits of Rodrigo and his partner, of his friends dolled up to the nines sharing drinks, and of Black and Brown queer folx feeling themselves — by themselves and with each other — paint a different picture of the favelas. It’s hard, certainly, but it’s also beautiful, fabulous and teeming with love.

“The work that I’m doing is for us, for the Black community in the peripheries, for us to see ourselves in a better light,” Rodrigo says. “I want us to celebrate the things that we actually have to celebrate: we’re beautiful, we’re powerful, we’ve been through so much, and we’re still here and strong and fighting. I’m doing this so we can realise that we deserve to feel beautiful. We deserve to be loved.”

Here, Rodrigo tells us about capturing Black queer joy in the favelas, the persistence of radical love in a police state and using his work to change the narrative about his community.

What was it like for you as a young creative to grow up by the water in Barra de Guaratiba as opposed to metropolitan Rio de Janeiro?

It’s very unique. It’s a fishing village, so it’s kind of a more primitive way of living. We’re very chill and easygoing people here, so it’s like we’re on vacation all the time. Growing up here, I had to cross a pretty big bridge to get [to school], and my former primary school was like 20 meters from the ocean. Right behind me there’s the mangrove [of the Guaratiba Biological Reserve]. Growing up here, there’s that feeling of always being connected to the environment, to our surroundings and there’s a respect for nature. Everything here is just so dreamy: the scenery, the sunsets… it makes me feel in love with life. This dreamy experience defines a lot of my photography. It’s the way that I’m used to seeing the world: passionate and in love with everything that I see.

How did you get your start taking photographs and what drew you to photography?

I was born in 1992, the end of film, and it took a while for [my family] to get a digital camera. I used film for quite a long time and I just loved it. I remember [taking] a picture and it would take one or two months for my family to develop it. It was always that surprise and expectation to see the outcome of the pictures. It’s always like that: even going to take a digital picture, what you see through the viewfinder sometimes is very different from when you look at the picture itself. The thing that I think clicked and made me really interested was when I was photographing in the rural side of Rio, not within the city. There was this huge lake, and I was photographing the little insects. At the time I was studying biology, and thought I’d start with wildlife photography and documentary conservation. I took this close up of a dragonfly and I wasn’t expecting the photo to look the way it looked. From there on, I just kept going.

At what point did you graduate from dragonflies to people?

I was still studying biology in Australia on a scholarship from the past Brazilian government — otherwise I wouldn’t have the cash to do that. I was saving money to take a trip and decided to go to South Asia — Thailand, Cambodia and Singapore — and I was going there thinking I would take mostly landscape shots and wildlife shots. But when I got there, the people were so interesting and open to being photographed. I couldn’t really connect with them through verbal communication: the camera was what was connecting us. I never stopped taking portraits after that.

When did you decide to specifically photograph the Black queer community in the favelas for your Carioca, Negro, Queer series? I was really moved that you were doing this project, especially in the face of the political climate Bolsonaro has fomented in Brazil.

This is the longest I’ve been in Brazil ever since I moved overseas because of the work that I’ve been doing with the Black community here. When I was back, I didn’t know what I wanted to photograph, and felt like I missed a purpose. At one point I was studying American culture and American literature, and was looking at the Black Lives Matter movement and the Civil Rights movement. I wanted to study the whole Black history in America and my own country. I wasn’t part of the community, which is mostly within the city of Rio. I wasn’t really going into the city and seeing what was actually happening; life is really slow where I live. I was either always missing everything or the LGBTQ community here wasn’t alive at all. When I got back, it was so different, the way people were expressing identity. Everyone was very shy before and now things are changing. We’re getting more comfortable with ourselves, standing up for ourselves and being honest for ourselves. Seeing people come to life and being the best of themselves was really inspiring. There’s also a lack of representation of the Black suburban life in Rio, which is highly marginalized. I wanted to break that down and do something for my community to uplift them. I documented my impression of what was happening with my community, how they’re coming to life, unionizing and fighting, realising that we are stronger together.

What personal realisations have you come to photographing and documenting Black queer identity in the favelas of Rio and in Barra de Guaratiba?

Where I live is very isolated from the rest of the city. It’s like I’ve been sheltered from everything that we see on the news about crime and violence and everything. The image that people that are sheltered from that media have is that all these things happen within the favela. I realised that that’s not the case at all. There’s less interference from the state there, so people are neglected with health, security and everything else. The danger for them is the police, who a few weeks ago killed 24 people in a drug raid. I started to admire people who came from the suburbs and favelas. It’s really unfair how we’re portrayed, and seeing everything that the government already does to our people, the police coming in with all this rage. The police and government are the threats, and people have to do what they have to do to survive.

And within all of this framework of state-sanctioned violence, you capture a persistent joy.

I’m doing my best to portray my community in the best light. The way that I see ourselves is the way that we are, with all the beauty and the power and the strength despite everything that is happening. I hope everyone can wake up to the reality of what actually is going on here. I’m hoping my work will put my community in a position to break down everything and assure the way that we want to be seen and deserve to be seen. It is time for us to tell our own narratives. Our stories have been told by the eyes of others for such a long time — we have a voice and a space now.