In 1968, nine-year-old Russell Peacock and his family moved from outside London to a brand new suburban enclave that had cropped up on the edge of farmlands around Rochester, New York. “It was surreal, strange, and foreign to us,” Russell says, remembering a golden era of neighbourhood parties and barbecues replete with local moms sporting blonde wigs and white go-go boots.

“Our house was three times the size of our old one, and we had two cars, a telephone, and fake wood paneling in the family room. It was the American Dream,” he continues. “My dad was a Little League coach but he had no idea how to play baseball. My brother and I were a bridge to American society because kids assimilate a lot faster. Within two or three years I lost my accent because I didn’t want to stand out. When I started school, I had to stand up in front of the class and talk about where I came from, like I was from Mars.”

By mid-century, the twin engines of entertainment and advertising seized upon the suburban industrial complex to craft a gold standard of middle class success that could be bought and sold. Within the fairytale image of home ownership, a white picket fence, 2.5 children (and a dog), lay deeper truths of white flight, redlining and environmental racism.

“I never aspired to that kind of lifestyle,” says Constance Hansen, Russell’s wife. “My mom was born and raised in Harlem, and she was a single mother raising two kids. We lived in Southside Chicago, a rooming house in Miami and then we moved to Fort Lee, New Jersey, literally on the George Washington Bridge. I was always rebellious and wanted to be a badass. The suburbs weren’t even something I was thinking about.”

That is, not until 1996 when British Vogue commissioned Connie and Russell — as husband and wife photography team Guzman — to shoot a fashion editorial for the magazine. In that moment, they decided the time had come to turn the nuclear family upside down for “The Suburbanites.”

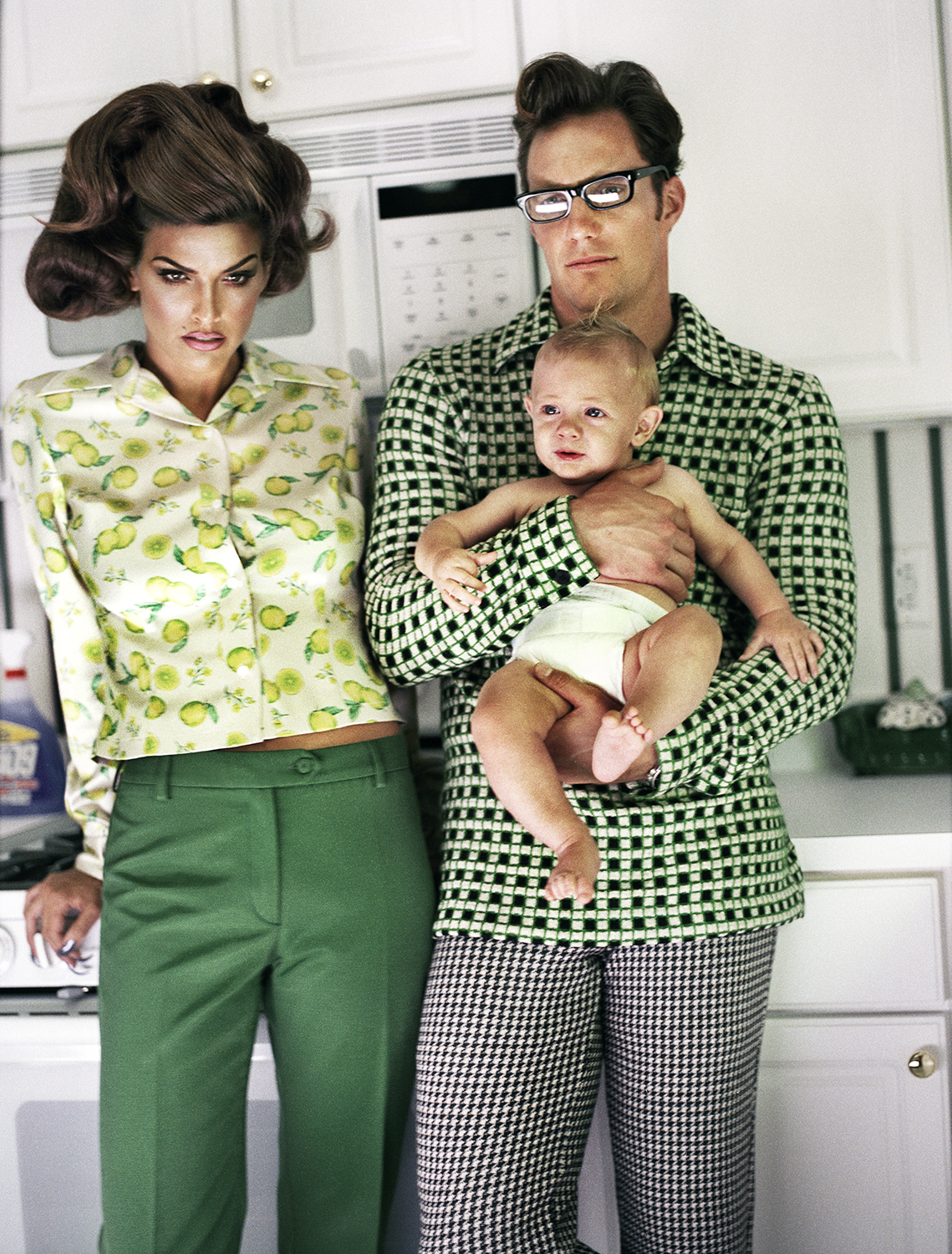

By the mid-90s, suburbia had become a surreal landscape, revealing certain cracks in the American psyche. Removed from their roots, nuclear families became isolated and neurotic, filling their emptiness with consumption. It was the perfect backdrop for a playful, tongue-in-cheek celebration and critique of the very cycle of consumption that fashion photography helped to perpetuate.

From the outset, Connie and Russell positioned Guzman as the quintessential outsider in a notoriously exclusionary industry. Long before the term “disruptor” was in vogue, Guzman embraced a subversive approach, blurring the boundaries of gender, identity and beauty in their work. After getting their start working with fashion designer Geoffrey Beene in the late 80s, Guzman was on the rise.

Allergic to labels, Connie and Russell have never identified themselves by what they shoot: music, sports, fashion, dance, advertising, editorial, portraiture — it’s one and the same in their eyes. “We were a specialty item,” Connie says with relish. “They never asked us to do sexy because it would be so weird, but we just couldn’t help ourselves.”

But the 90s was the perfect time for their singular blend of iconoclastic charm. Budgets were high, and there was a firm boundary between the business and creative sides of photography. Whether collaborating on album art with Janet Jackson for Rhythm Nation 1814 and En Vogue for EV3, or crafting unforgettable campaigns for Louis Vuitton and Kookaï, Guzman was everywhere, dominating the billboards, music charts and the magazine racks.

Connie and Russell reimagined the landscape of suburbia with a sinister twist, while also delighting in its innate campiness. “We thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be funny if everything was fake and it turned out to be this scary place you can’t ever leave?’” says Connie, who took inspiration from The Prisoner, the 1967 British TV show chronicling the story of a spy who discovers he has been captured and sent to live in an elaborate prison cleverly remade as an idyllic village.

Working with stylist Jo Hambro, Connie and Russell assembled an all-star team that included models Shana Zadrick and Danny TMan, and descended upon Society Hill, a brand new suburban complex in Jersey City. Eager for their close up, Society Hill staff allowed Guzman to shoot in the model home that was fully staged down to the fake food in the kitchen. “They were so excited, they didn’t know what we were going to do,” Connie says.

Connie and Russell set to work on “The Suburbanites”, crafting a tale as old as time. She wanted it all: the man, the child, the house. But now that she’s got them, she’s quickly losing interest. Fortunately, he’s thanking his lucky stars and will gladly do whatever it takes to keep her satisfied. Whether that means giving her the Top Gun treatment in the bedroom, dancing the Frug or being Mr. Mom, he’s got it covered.

“The guy in the story is really happy. He thinks he’s the cat’s meow,” Russell says. “And we just went with it. We were literally laughing the whole time. There’s that one shot where they are dancing in the living room and we were giving them directions like, ‘Dance harder!’”

Credits

All images © Guzman. The Suburbanites, British Vogue, 1996.