“We are all pilgrims who seek Italy,” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote in a poem after returning to Germany following a two-year sojourn across the peninsula in the late 18th century. Intoxicated by the intense passion that fuelled the nation’s imperial history, Goethe returned to his diaries on the road to pen his famed travel book Italian Journey four decades later.

Amid the romance, adventure and splendor he encountered in Venice, Verona, Bologna, Naples, and Rome, it was the untamed island in the south that captured his imagination. “Italy without Sicily leaves no images on the soul: here is the key to it all,” he wrote while visiting Palermo — a city that he admitted was “easy enough to survey, but very difficult to know”. Now, a new photography exhibition in Turin, Palermo Mon Amour, acts as a love letter to the city.

Founded in 734 BC by the Phoenicians as Sus (“flower”), a subtropical paradise on the Mediterranean Sea, the city (now called Palermo) is the crown jewel of Sicily. Over three millennia, the island has been caught in the relentless tide of imperial forces on the rise. After the Kingdom of Italy annexed Sicily, the people rose up and took to the streets of Palermo in 1866. Theirs was a popular cause, and could only be crushed by martial law.

As the nation spiralled into fascism, longstanding Anti-Sicilian prejudice and policy rose in the north. After Mussolini’s ignoble defeat, Palermo welcomed arriving American troops with open arms but, truth be told, the greatest enemy of the people was already inside the city’s ancient walls: Cosa Nostra. Although its origins are shrouded in secrets and lies, the mafia was becoming what then-politician Leopoldo Franchetti described as an “industry of violence” by 1876.

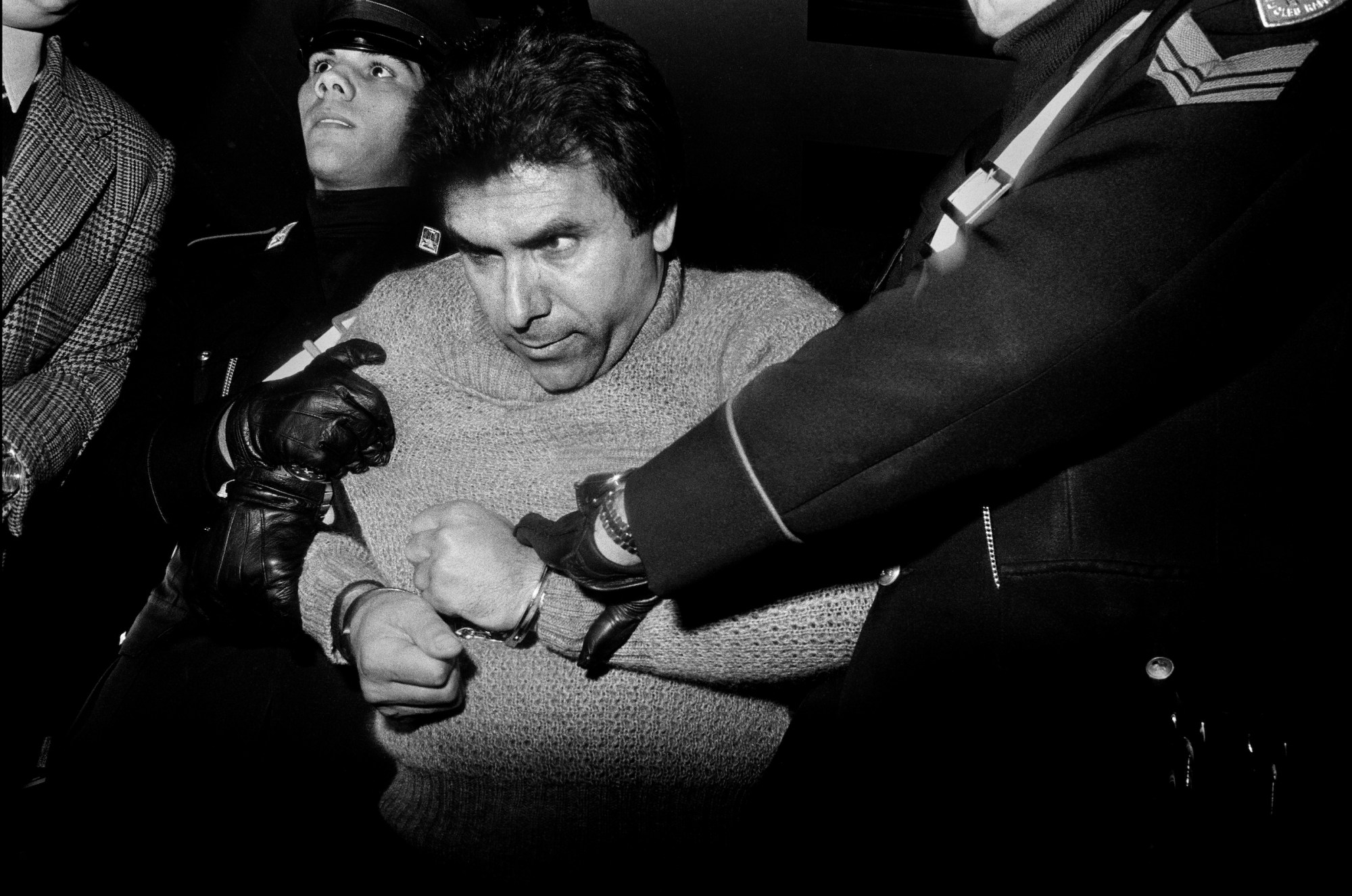

Although Mussolini actively suppressed their influence, the mafia came back with a vengeance after the war and transferred their power base from the countryside to the cities. Palermo was effectively occupied while omertà (the code of silence) reigned supreme. The streets became battlefields between warring families, while the bodies of trade unionists who refused to comply were gunned down in broad daylight, turning the city into killing fields.

But Palermo native, Letizia Battaglia (1935–2022) fought back, using photography to break the code of silence. In 1971, Letizia launched her photojournalism career at the age of 40, using the camera as a tool for justice. As the first Italian woman photojournalist at a daily newspaper, L’Ora, Letizia centred the voices of murder victims and their families in her work, chronicling the harrowing impact of organised crime over a period of 20 years.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

“I was sure they’d kill me. It gave me courage,” Letizia said in the 2019 documentary film, Shooting the Mafia. Despite death threats, anonymous letters and smashed cameras, Letizia persisted, creating over 600,000 images that she once described as “an archive of blood”. But exposing their crimes was not enough; Letizia became a politician and worked with investigating magistrates to bring about the convictions of 474 mafia members in 1986.

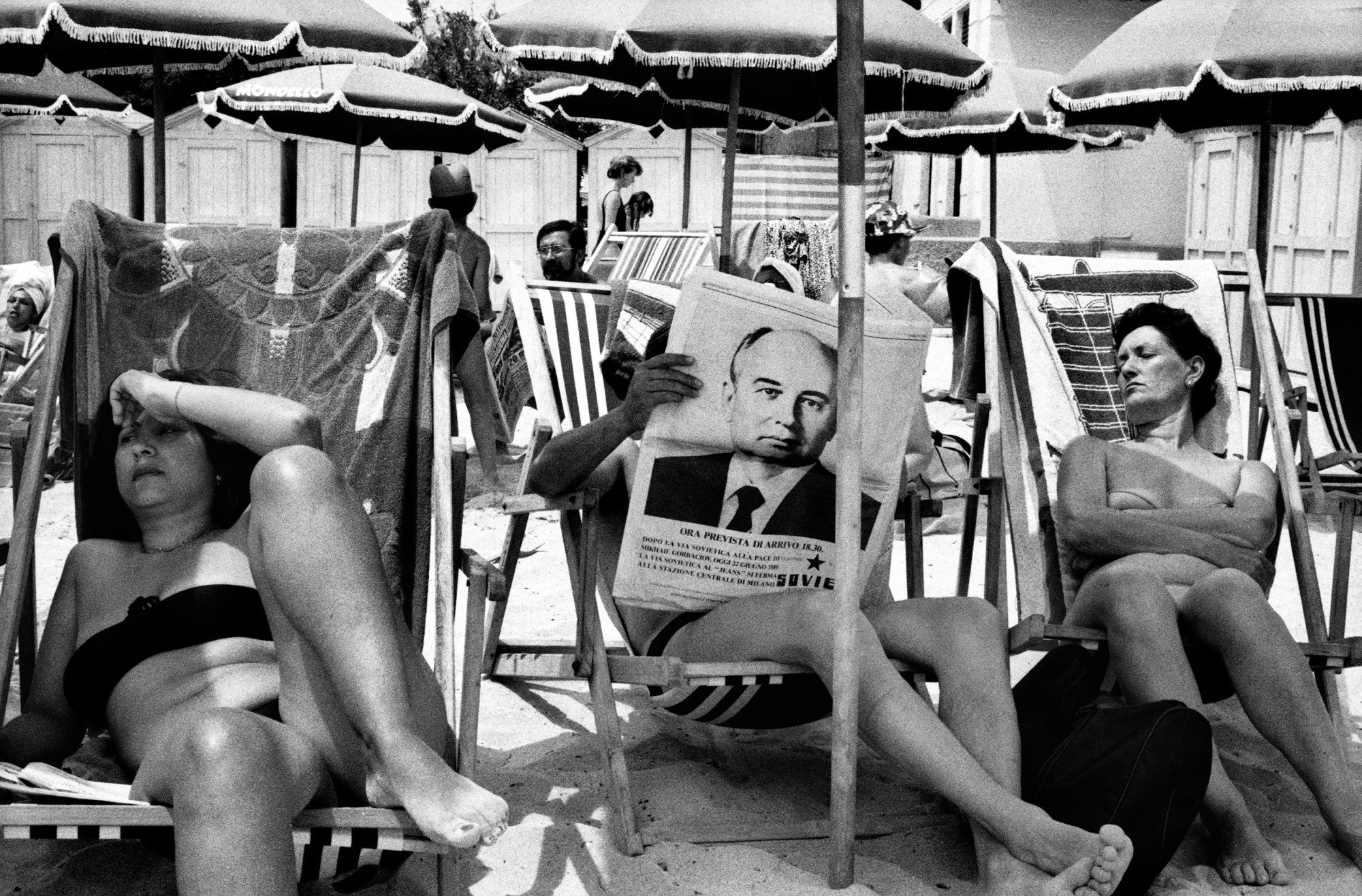

The Palermo Mon Amour exhibition, from Fondazione Merz in partnership with the Centro Internazionale di Fotografia Letizia Battaglia, honours the first anniversary of her death. Curated by Valentina Greco, the exhibition explores the transformation of Palermo between the 1950s and 1992, through the work of Enzo Sellerio, Letizia Battaglia, Franco Zecchin, Fabio Sgroi and Lia Pasqualino. Tracing the threads of postwar Palermo as it emerged from the shadows of conflict only to face the ferocious assault of mafia clans vying for power, the exhibition offers a layered, lyrical look at a city shrouded in myth.

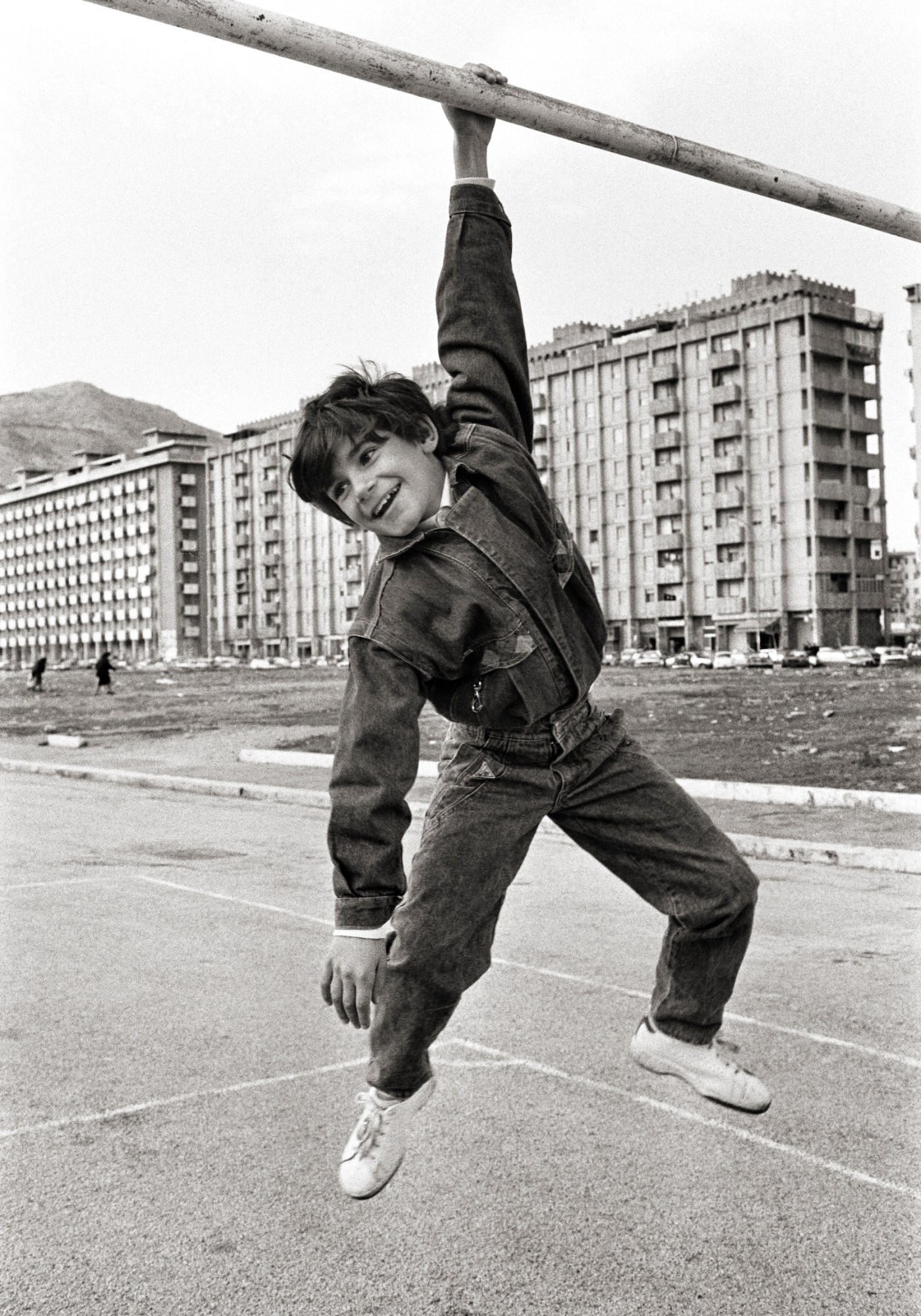

Coming of age in Palermo during the early 90s, Valentina witnessed the generational changes sweeping through the city, forging a deeper understanding of the role photography has played in shaping its image. “Many people think Palermo is a city of violence, degradation, darkness, and decay but there are also contradictions,” Valentina says. “There have been so many periods of different groups occupying the city, meaning it has these juxtaposing styles and layers of history. There’s the aristocracy, student movements, the punk movement, and all this creativity. The photographs in the exhibition look at how previous generations from the 1950s, 60s, and 70s were reacting to the ups and downs of city life.”

The exhibition begins with the work of Palermo native, Enzo Sellerio (1924–2012), who got his start as a photographer in the 1950s just as the nation was emerging from the shadows of war. Embracing the allegorical mystery and raw majesty of Italian Neorealism, Enzo adopted an approach that he described as, “Watching the centre from the periphery to find that the periphery is the centre”.

“There’s an intimacy between the photography and the cinema within this exhibition, especially in Enzo’s work,” Valentina says. “You can see the 1950s was the start of it all.” But by the 1970s, the violence on the streets of Palermo had become too much to bear. He ceased photography until shortly before his death, and devoted himself to his own book-publishing house.

It was at this time that a new style of photojournalism emerged, one heralded by Letizia and Franco Zecchin (b. 1953). Hailing from Milan, Franco arrived in Palermo in 1975 and began working at L’Ora at the encouragement of Czech-French photographer Josef Koudelka. “L’Ora was published twice a day; that shows the speed at which the photographs in that period were being shown,” says Valentina. “It was even more powerful than the words that were written because it was giving a glimpse at what the actual situation was.”

Deeply attuned to the darkness and desolation of the raging mafia war, Palermo native Fabio Sgroi (b. 1965) started photographing the city’s underground punk scene. Over a period of two years, he chronicled local anarchists, radicals and drunks while also playing in a punk band called MG. He fell into photography without a plan, only to end up joining Letizia and Franco at L’Ora in 1986 when the punk scene started to wind down. Although Sgroi was just 20 when he joined the newspaper, this made him the perfect person to document the burgeoning student movement, protests, occupations, and dynamic cultural changes sweeping the city at the time.

Lia Pasqualino hails from a Palermo family of artists and intellectuals that includes her grandmother, Lia Pasqualino Noto, a painter with the Quattro group. In 1986, Lia took a course with Letizia and Franco, and from that moment on has been dedicated to photography. Working across portraiture, photojournalism and set photography, Lia’s work captures the city on the precipice of a new era unfolding before her eyes.

Seeing the beauty of her hometown intricately intertwined with the conflicts that have defined the second half of the 20th century, Valentina sees Palermo Mon Amour as an extension of the people’s determination to fight back and survive. “Palermo is like a bomb that explodes and after the explosion there’s haphazard remnants on the ground,” she says. “How do you rebuild from that? That’s the foundation.”

Palermo Mon Amour is on view through September 24, 2023 at Fondazione Merz in Turin.